Reading the Collections, Week 51: Mrs Muir and Mrs Muttoe

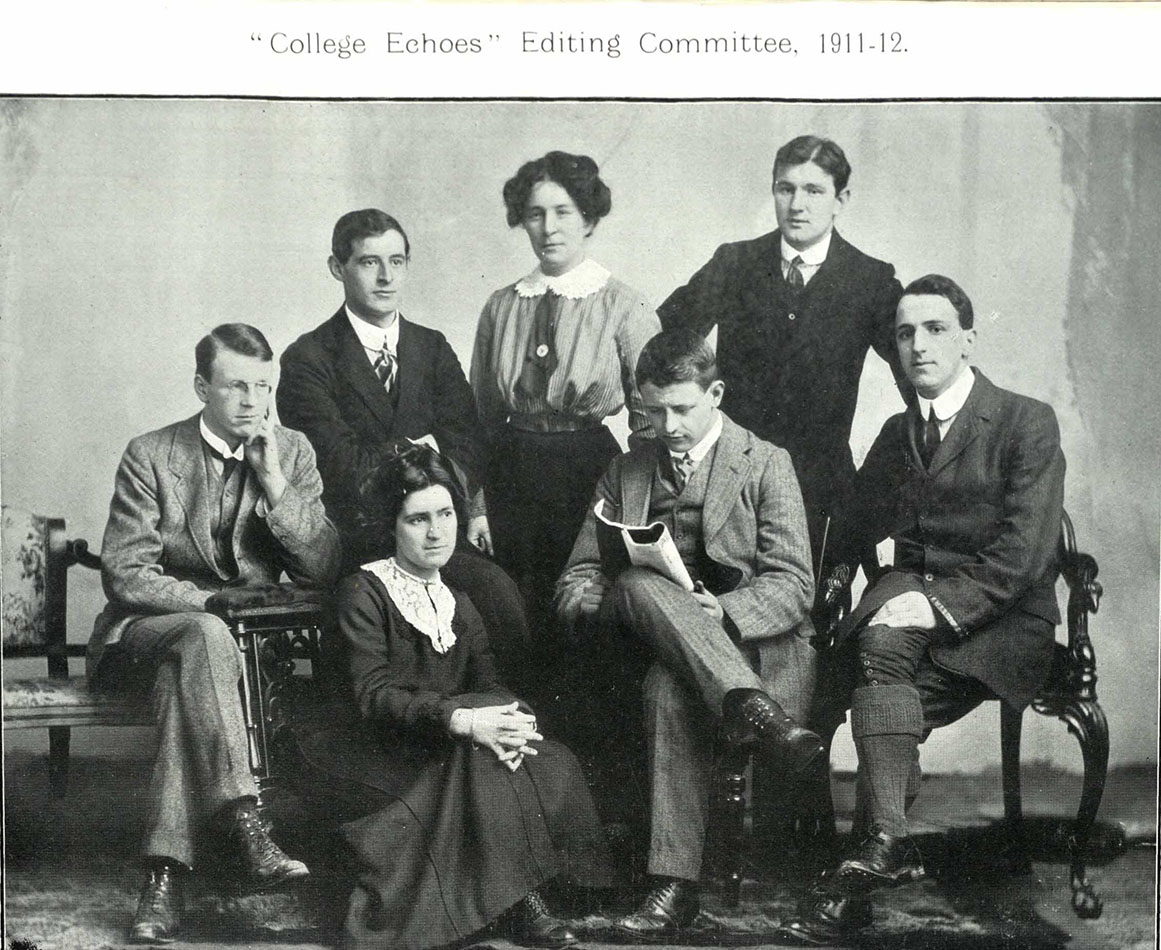

It seems fitting in the week of St Andrews’ own poetry festival, StAnza, to feature one of our literary collections. I have chosen Willa Muir, poet, novelist, diarist, translator and St Andrews graduate. She was born Wilhelmina Anderson in Montrose in 1890, and came to St Andrews in 1907 to study classics, modern history and then English literature. She helped to edit College Echoes and took part in various University societies. She aimed for a career in teaching before meeting and marrying Edwin Muir, a leading light in Scottish poetry, in 1919. They travelled and worked on the continent as well as in various places in England and Scotland, and also America, teaching, writing and translating to make a living. Long before I had heard of either Muir, I was reading their words via those of Franz Kafka. I didn’t know that Kafka was initially translated by the Muirs. The Trial has long been a favourite novel of mine, and when I checked my old Penguin Modern Classic at home, it was indeed the version by the Muirs. Or sort of, as my Penguin gave the translators as Wills and Edwin – sad that she lost her gender and identity through a typo, but perhaps she might also have been amused by it.

Amongst the papers held at Special Collections are manuscripts of some of Willa’s short stories, poems and essays, a collection of letters to the Muirs and letters between Willa and Edwin, as well as her journals and diaries, held as ms38466.

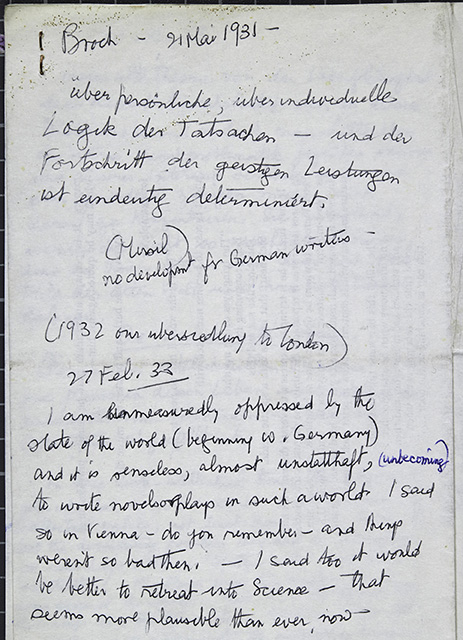

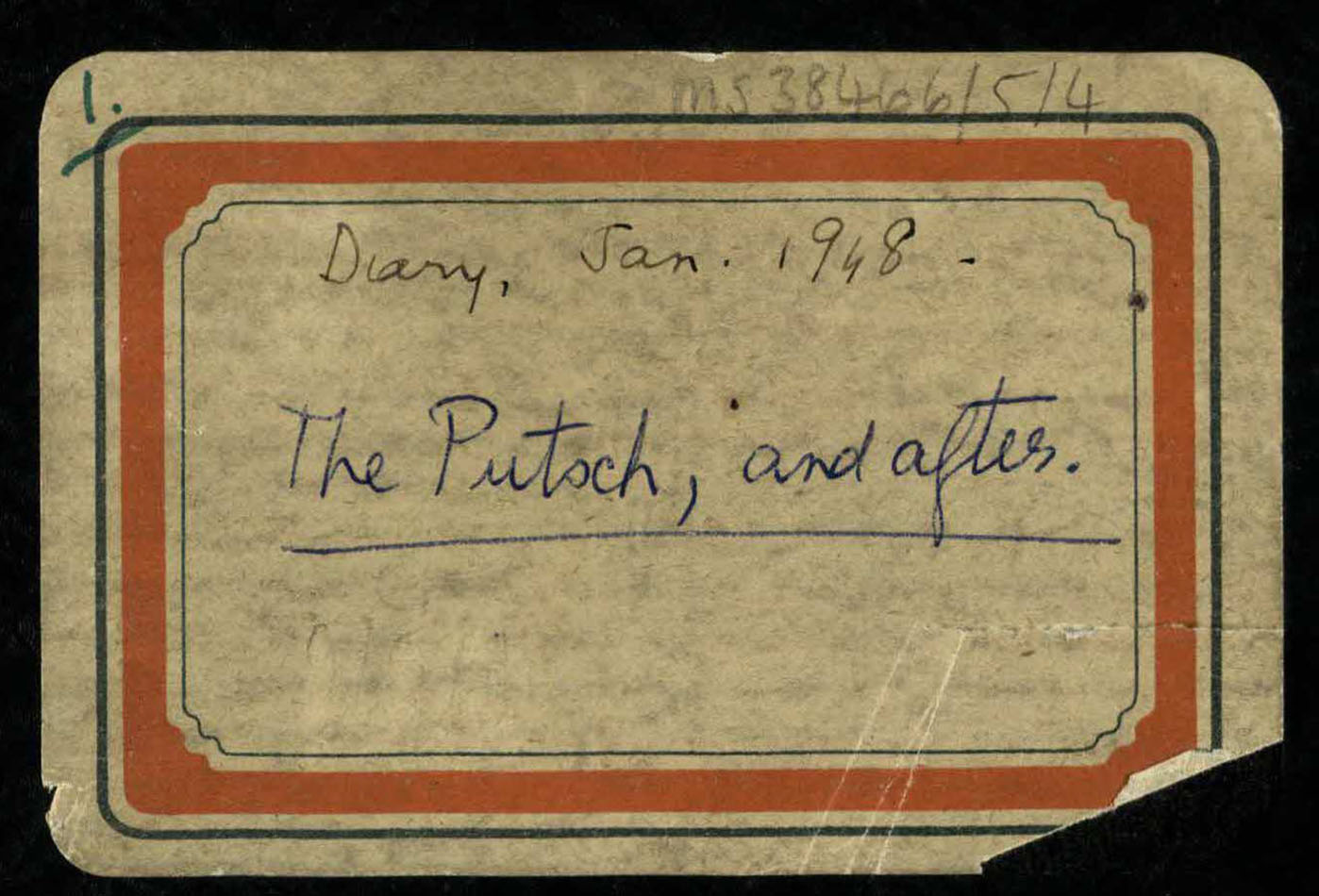

I had previously read some of her fascinating diaries kept while they lived in Prague from 1946-1948, where Edwin was Director of the British Council. Their stay there included the putsch or communist coup which led to the ‘suicide’ of Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk. The diaries have insightful comments on public demonstrations, political manoeuvring and views of the ordinary Czech people. The uncertainty of not knowing who to trust, the feeling of being spied upon, arrests and interrogations of their friends, and the difficulty of being foreigners subject to any whim of the law, led ultimately to their decision to leave. Much of this was published in Willa’s autobiography Belonging: a Memoir so I decided instead to choose an unpublished novel to read.

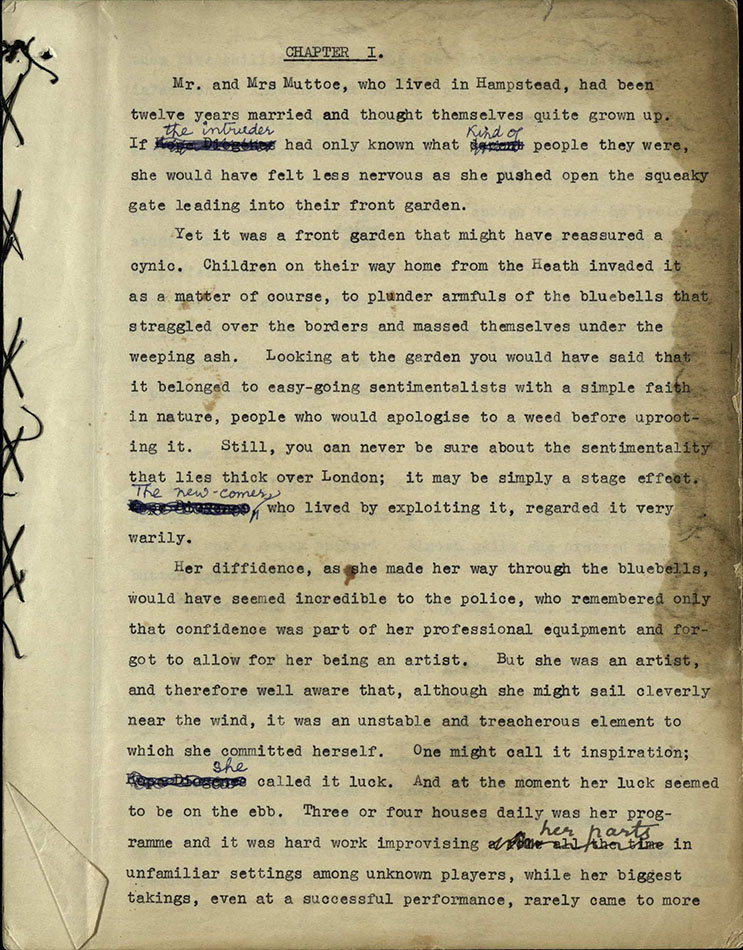

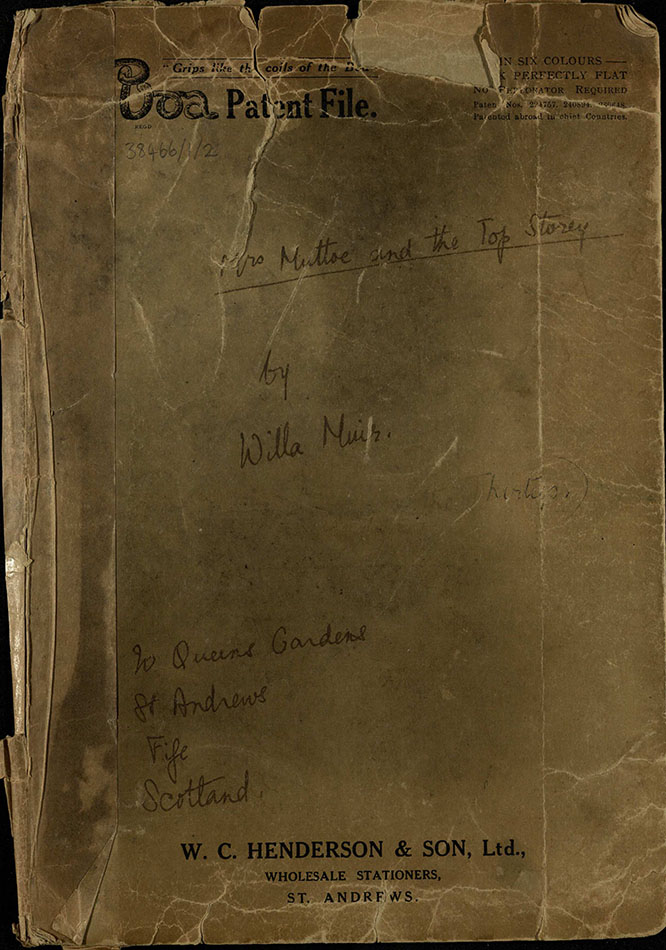

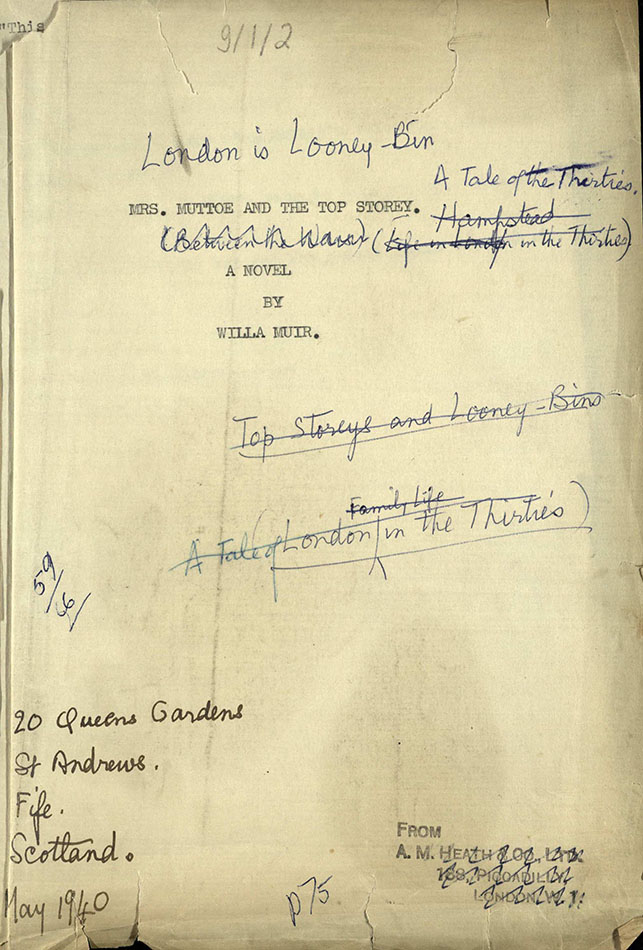

Mrs Muttoe and the Top Storey was written in St Andrews, where the Muirs lived in Queens Gardens, and perhaps was named after Muttoes Lane, a handy route from Market Street to North Street. Willa finished it in May 1940. She had already published a number of works by this stage but it is not clear whether she ever sent it for publication. There is no doubt that it is thinly veiled autobiography of the 3 years they had spent in Hampstead, London. Willa and Edwin become Alison and Dick Muttoe. The novel starts with an amusing story of a confidence trick by a woman posing as prospective domestic help. This grabs the attention and keeps you reading. It is followed by anecdotes on going to various agencies in search of a cook-housekeeper, other escapades with cooks and housemaids, the acquisition of a dog, tales of their son Peter, poking gentle fun at an acquaintance who had created a personality cult around himself, and accounts of social gatherings.

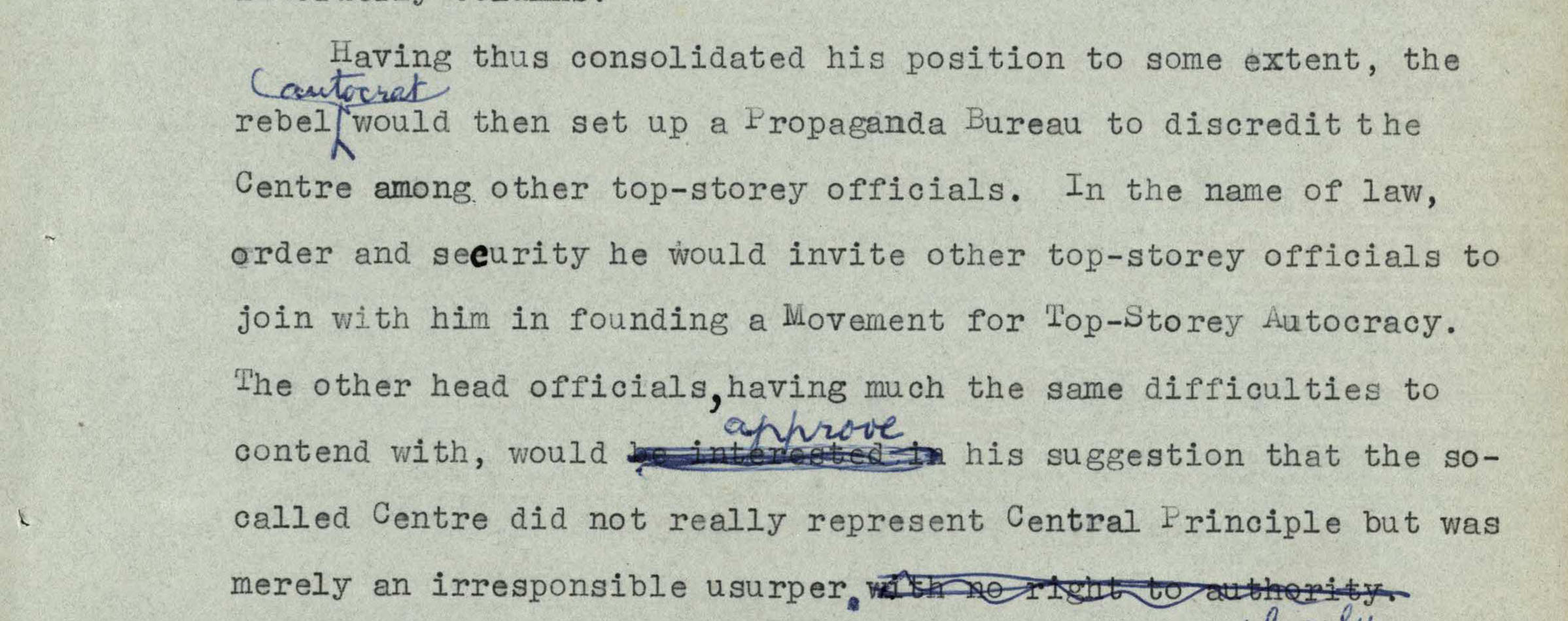

In the midst of all this domesticity is a rather strange house metaphor in which Willa imagines the human body as a house, with the head official who tends towards autocracy in the top storey, and the Centre as the mysterious invisible lower part of the building which runs routine operations. The two are always at loggerheads. It seems to represent head versus heart or emotions, and she does try to develop this later but it never seems satisfactory.

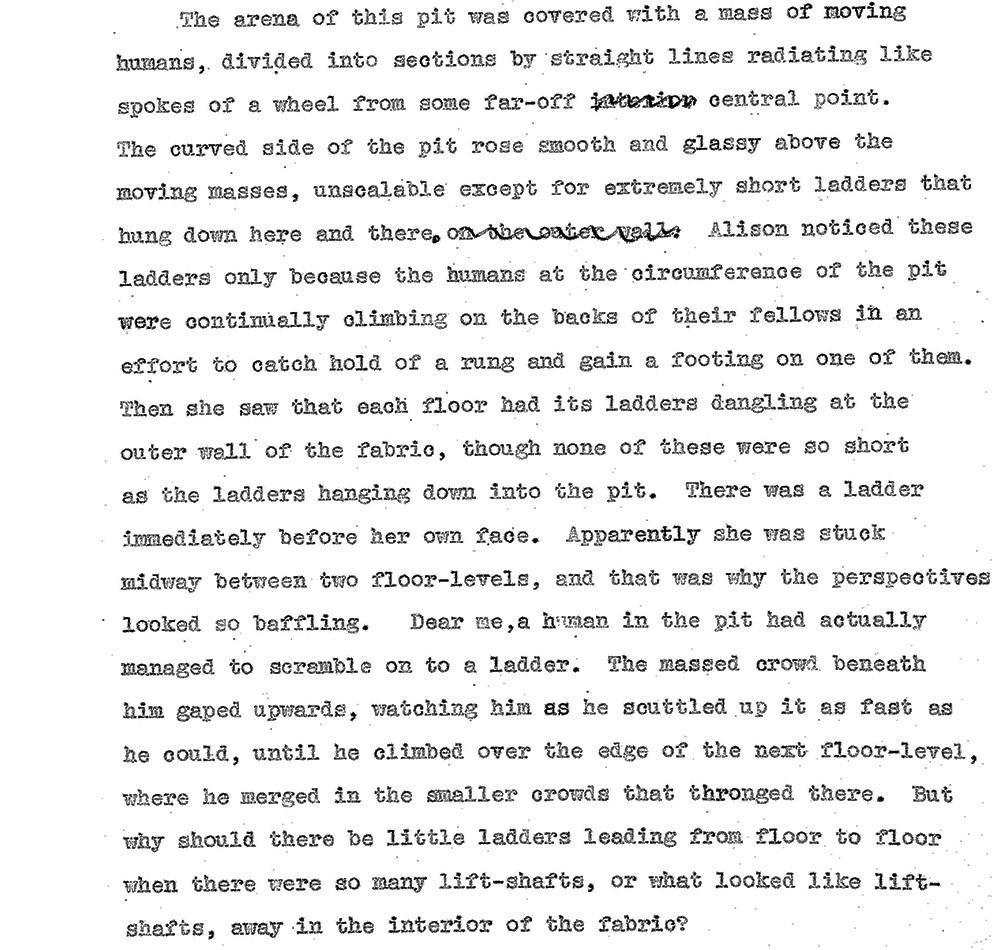

Then it turns nightmarish, probably influenced by her translations of Kafka, referred to as Garta in the novel. Firstly there is a sinister visit from a bowler-hatted gas company official who insinuates tampering with the gas bill, then the Kafka-esque nightmare of being trapped in the Money Fabric, her metaphor for the ceaseless wheel of capitalism and industrialisation. She finds herself stuck on the outside of a great glass dome, looking down on workers labouring away like automatons in a pit, while aspiring men strive to work harder to reach the higher balconies by ladders and trap doors, each balcony representing an income threshold. But there is no way out for anyone who doesn’t want to be a part of the Money Fabric, with everyone under surveillance and arrests by mysterious authority figures possible at any time.

The novel is a strange mixture of the purely domestic, the tragi-comic struggle to hire a suitable cook and housemaid, and visions of a dystopian future, with the house metaphor about the Centre and the autocrat in the top storey, the Money Fabric and the Power Age which make her wish to leave London for a rural retreat in Scotland. Perhaps as 2 novels it might have worked better, the light satirical view of life in Hampstead with servant problems given separate treatment from the paranoid dark dystopian future. The Money Fabric is certainly an interesting idea which I would like to have seen taken further, and her later experiences in Prague would have given her plenty of material to draw on.

It is also partly a feminist novel, showing a woman working in her own right, but also a little annoying that she gives up her own work for her husband, so he can write what he wants to uninterrupted, while she earns a living by translating, and dealing with the household, the child, the dog and the servants. Perhaps if Edwin had dealt with the household and left Willa to write in peace in the top storey she might have had more time to edit this novel. She has an entertaining style, her gripes with modernity are still relevant today, and it gives an insight into the Muir household and lifestyle. It is a privilege to have been able to read this literary creation that few others have had access to.

Maia Sheridan

Manuscripts Archivist

There is a small exhibition at the Byre on Virginia Woolf’s connections with St Andrews which includes a section on Willa Muir. Details are available here: http://virginiawoolfmusic.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/events/