Ten Minutes in Murderland. Horror and Sensationalism in The St Andrews Citizen, Week 3: Jack the Ripper.

This is the final part of our mini blog series featuring sensational headlines from The St Andrews Citizen newspaper. Spoiler alert: contains graphic descriptions of murder – not for the faint-hearted!

There are few people unfamiliar with the name ‘Jack the Ripper’, given to the unidentified killer who stalked the streets of Whitechapel, London in 1888, murdering and mutilating a succession of female victims. The desire to uncover the Ripper’s true identity and understand the motivations behind his horrific crimes has persisted through the years, with a multitude of works written on the subject, countless individuals nominated as the perpetrator, and even a term – Ripperology – coined to describe the study of the case.

Police investigations considered ‘Jack the Ripper’ a potential suspect in eleven murders committed in the highly impoverished area of Whitechapel between 1888 and 1891. The first victim, Emma Smith, was robbed and sexually assaulted by multiple attackers in Osborn Street during the early hours of 3 April 1888, and later died from her injuries. Martha Tabram was stabbed to death on the 1st floor landing of George Yard tenement buildings on August 7. Contemporary reports linked the first two incidents to the next five murders, which took place between August 31 and November 9. However, Smith and Tabram’s injuries are no longer generally considered to be consistent with those of the other victims. The following women are commonly described as the ‘canonical five’ victims, because they are considered most likely to have been killed by a single perpetrator:

Mary Ann Nichols

The body of Mary Ann Nichols was found by a Police Constable in the early hours of Friday 31 August in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel. Her throat had been cut, and the lower part of her abdomen had been sliced open. Some of her front teeth had also been knocked out.

Annie Chapman

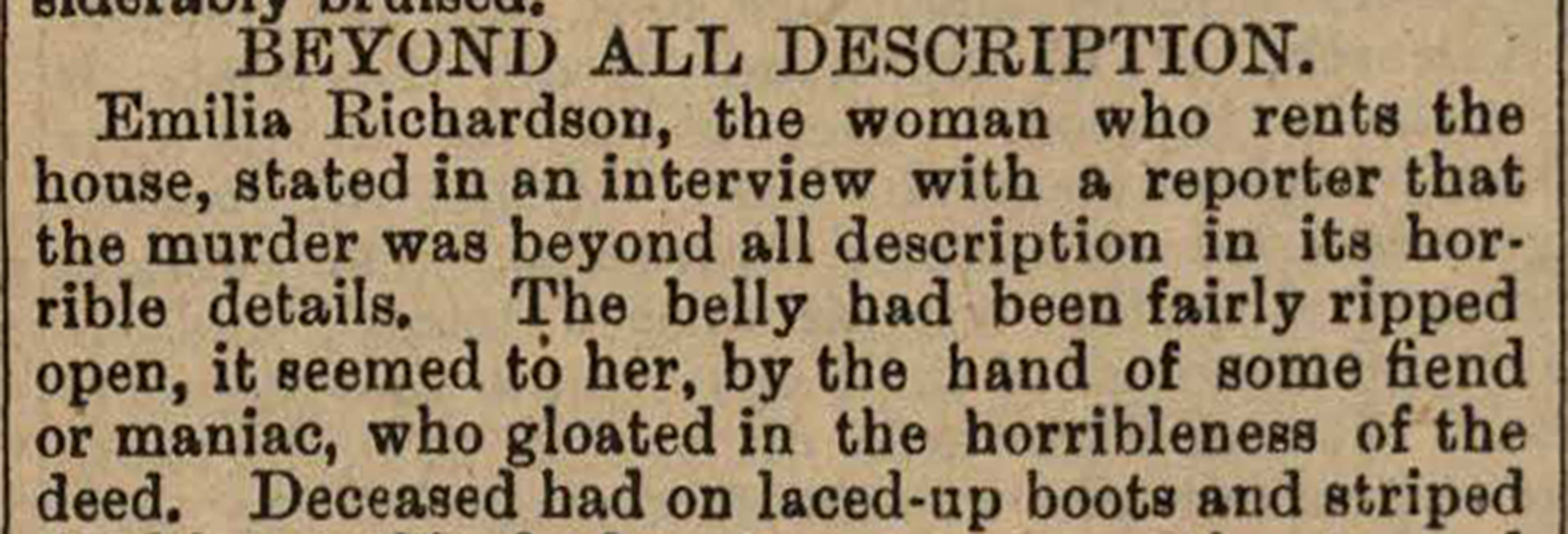

Annie Chapman’s body was found in the back yard by occupants of a lodging house in Spitalfields, at about 3:45am on Saturday 8 September. The newspaper report stated that her neck had been cut so deeply as to almost sever the head, which had then been tied back in place with a hankerchief. Organs had been removed through a large cut in her abdomen, and left strewn around the body. Read the Citizen article here.

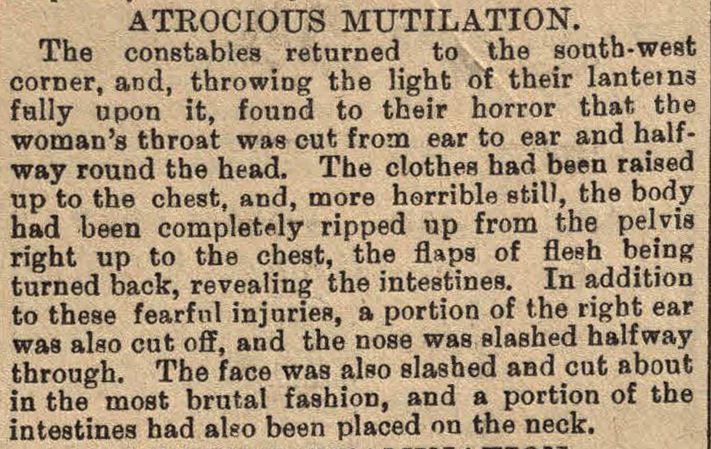

Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes

Elizabeth Stride was discovered in a courtyard in Berner Street, with her throat cut, shortly after midnight on Sunday 30 September. The blood was still fresh, suggesting that the crime had very recently been committed, and perhaps the murderer had been disturbed and forced to flee. Less than two hours later, the body of Catherine Eddowes was found in a corner of Mitre Square. As with the previous victim, her throat had been cut, but this time the body had been sliced up through the abdomen, part of an ear removed, and cuts made to the face. The left kidney and part of the uterus had been removed. Read the Citizen article here.

Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Ann Kelly was killed in the room she rented in a lodging house in Miller Court, Dorset Street, on Friday 9 November. The murder was reported by the man sent to collect her rent money, who when unable to obtain an answer at the door, looked in the window of the room to find the body in full view, along with a pile of removed body parts. When the Police forced open the door, they found that the victim’s face had been severely mutilated. Her throat had been cut, she had been disembowelled, and her heart had been removed. Read the Citizen article here.

As the Ripper’s killing spree progressed, the nation became hooked on every detail of the case. The drama unfolding in Whitechapel fed directly into the Victorian penchant for horror and sensationalism, which had been growing since the early 19th century when factors such as industrialisation and the rise of literacy levels caused reading to become increasingly popular as a leisure activity. The resulting demand for reading material, and the ability to print and distribute it widely and cheaply, led to the publication of penny serials primarily aimed at the working classes. Derisively known as ‘Penny Dreadfuls’, or sometimes ‘Penny Bloods’, these often heavily illustrated tales of romance, murder and adventure were designed to titillate, shock and captivate their audience. Newspaper reports of the Ripper murders borrowed heavily from this sensationalist style, including descriptive passages and gory details designed to horrify and engage in equal measure:

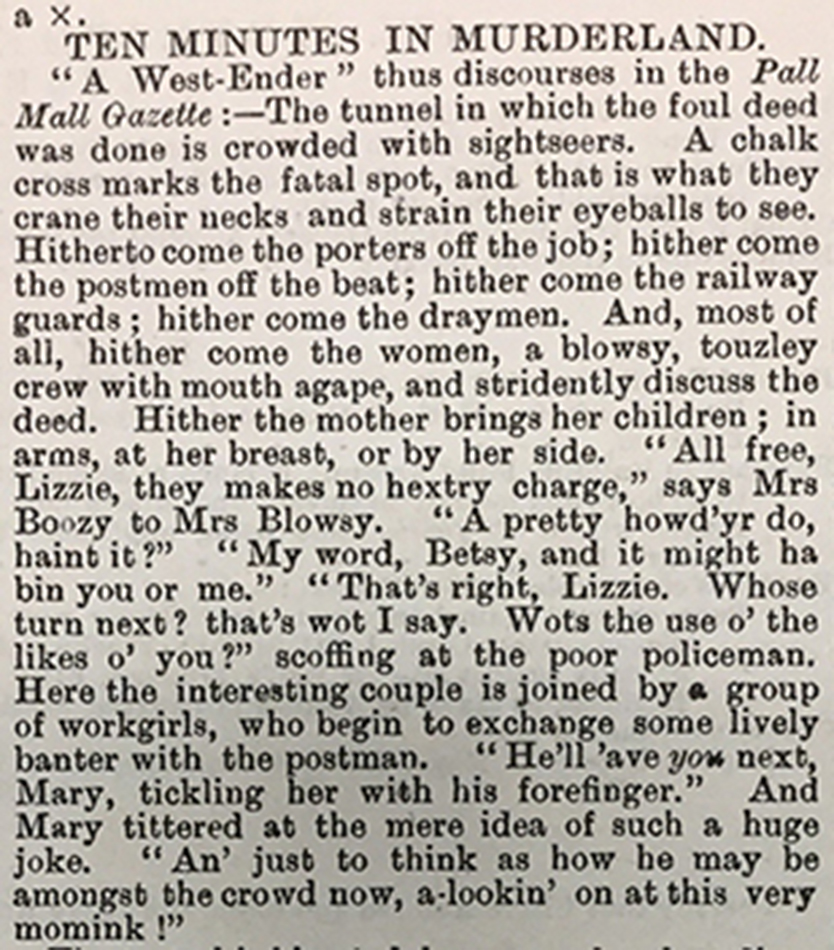

The press openly revelled in the public furore, and the mystery surrounding the identity of ‘Jack’ made him a blank canvas on which their assorted fears, opinions and agendas could be projected, allowing them to weave a fluid narrative around the murders which was designed to sell as many newspapers as possible. From an indictment of the failures of the Police and Scotland Yard, to an allegorical figure meting out justice to prostitutes in sinful Whitechapel, Jack played the central role in a story as great as the plot of any Gothic novel. Keen to maintain sales figures buoyed by this national obsession, the newspapers continued to publish stories and opinion pieces about the murders, even when there were no new developments. The Citizen scathingly condemns other newspapers for exploiting the situation in order to increase circulation, but ironically, just a few pages later, indulges in the exact same type of writing:

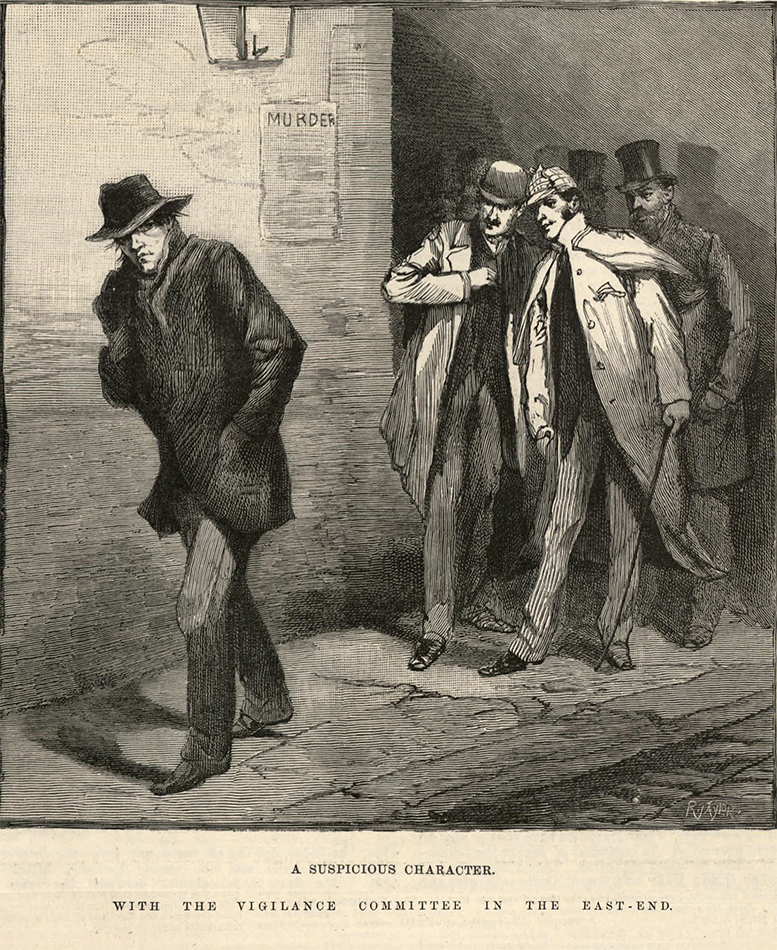

With the absence of a named suspect, the newspapers were obliged to describe the perpetrator in a manner suitably befitting the nightmare scenario they had painted. Using words such as ‘fiend’, ‘miscreant’ and ‘savage’, they filled column inches with wild speculation about the kind of monster who could be responsible for such heinous crimes:

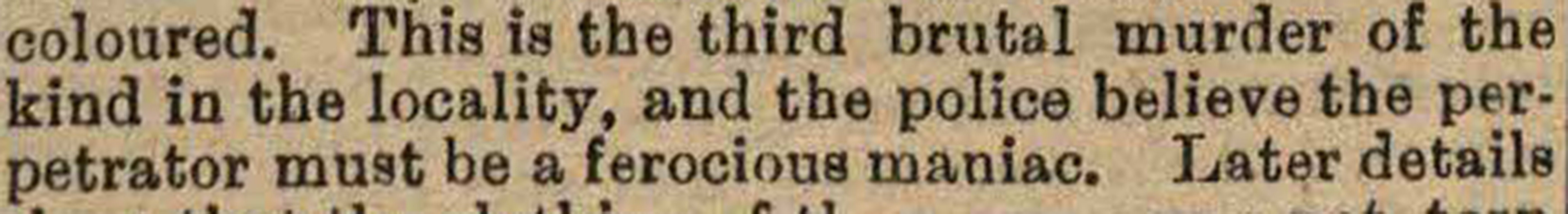

After witness reports claimed the perpetrator to be a man known locally in Whitechapel as ‘Leather Apron’ the press adopted the moniker:

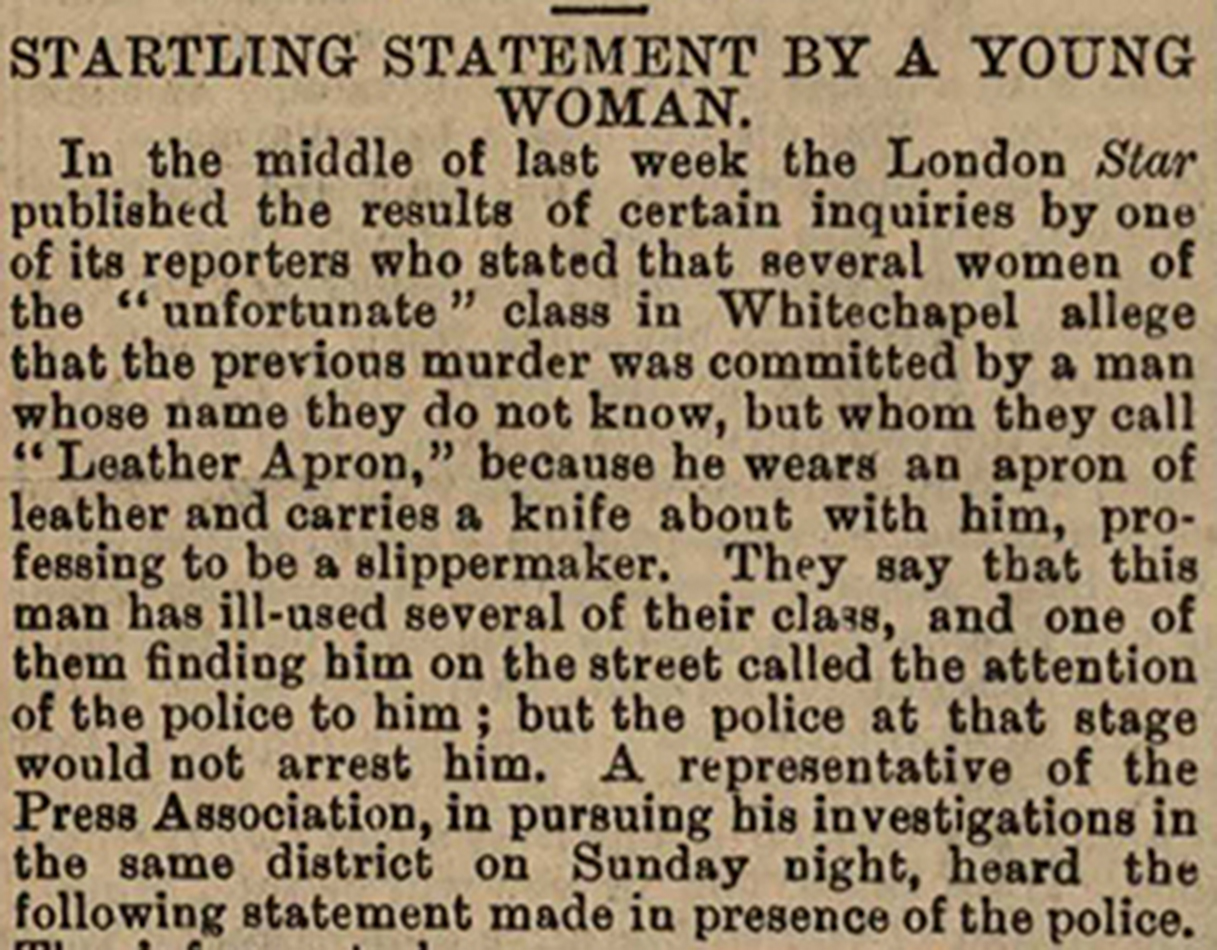

However, it was also hypothesised that the murderer must be a medical professional, on account of the anatomical knowledge displayed by the precise way the bodies were mutilated:

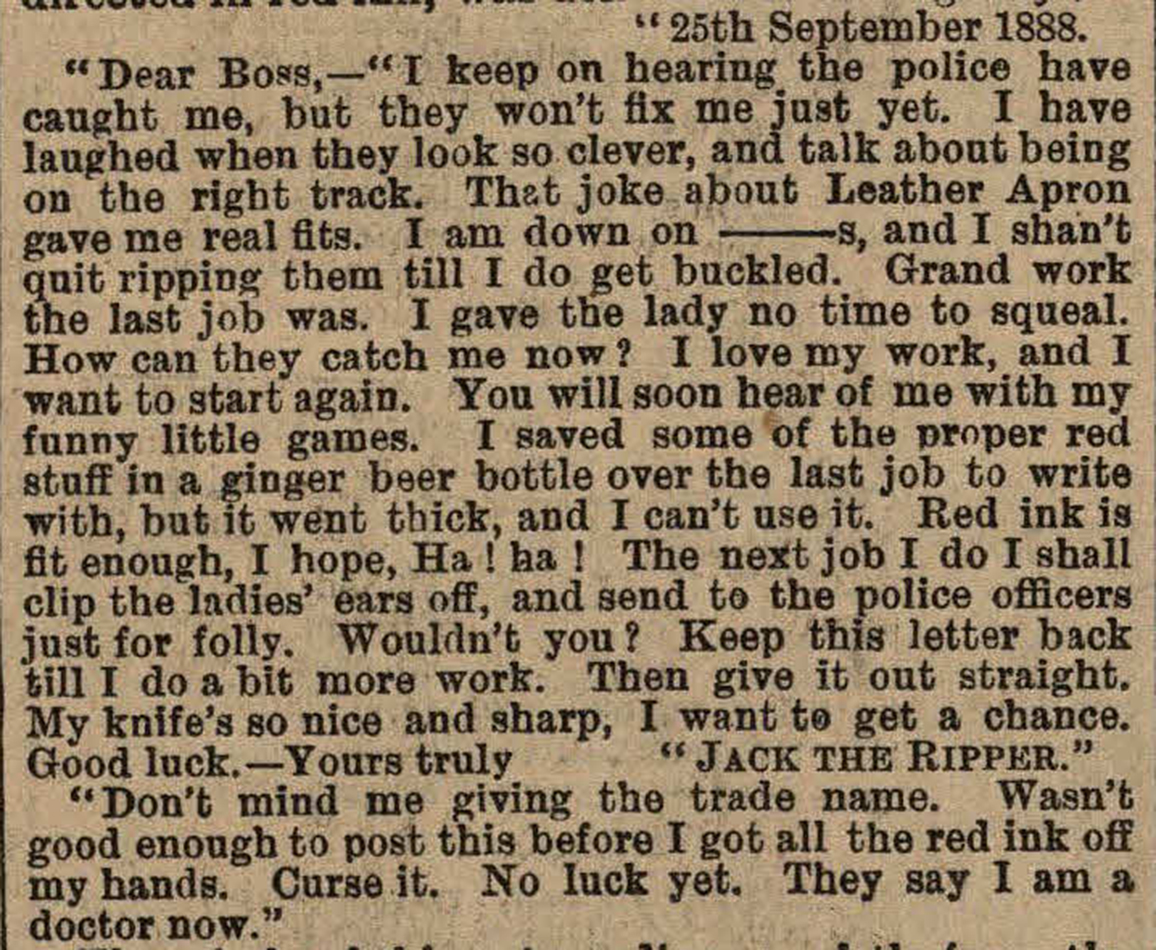

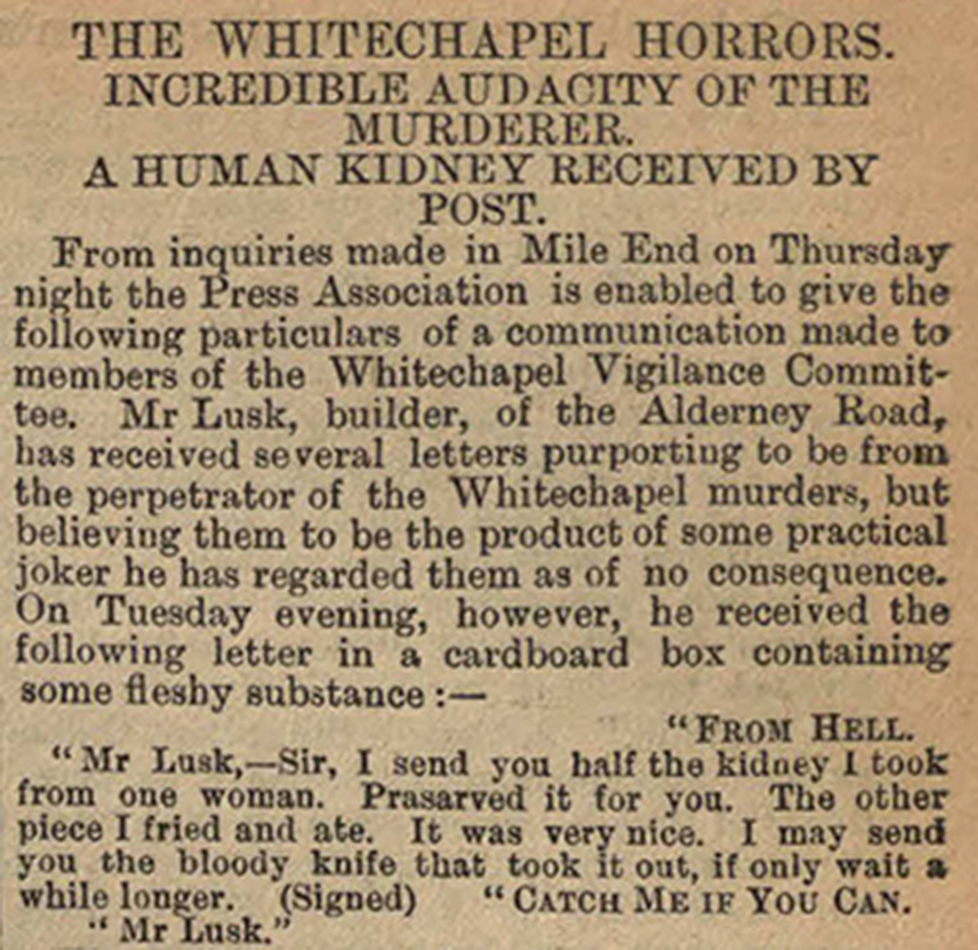

The name ‘Jack the Ripper’ was first used to sign off a letter written to the Central News Agency by an individual claiming to be the murderer, written on 25 September 1888, and posted two days later. The ‘Dear Boss’ letter, as it is known, was the first of three items which stood out from the plethora of hoax mail received in connection with the case. The author’s promise to “clip the ladies’ ears off” drew attention after the body of Catherine Eddowes was found on 30 September with a severed earlobe. The second piece of mail, known as the ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard and received on October 1, was also notable for containing information which ostensibly could only have been known by the killer. Finally, the ‘From Hell’ letter, postmarked 5 October 1888, was received by George Lusk, chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. It was not signed ‘Jack the Ripper’, and the handwriting differed significantly to that of the ‘Dear Boss’ letter and ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard. However, it was delivered with a box containing a preserved piece of kidney, which was tested and found to be human. The body of Catherine Eddowes, killed on 30 September, was found with one of her kidneys removed.

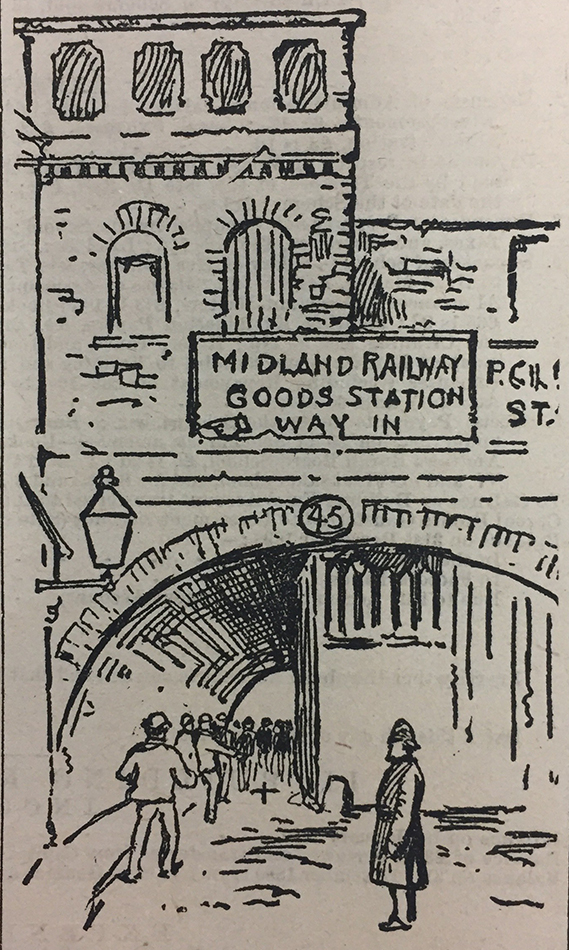

Despite extensive press coverage and resulting public awareness of the case, the police investigation was ultimately fruitless, and the perpetrator remained at large. The original case file included four other murders which took place after that of Mary Jane Kelly, the final being that of Frances Coles, who was found on 13 February 1891 under a railway arch in Chamber Street, with her throat cut and other injuries. The Citizen articles show that over two and a half years later, press interest in the case had not waned. If anything, they demonstrate an eagerness to revive the media frenzy created in 1888 – even going so far as to include an illustration of the crime scene. However once again, the newspaper reveals a dichotomy in its reporting style, juxtaposing a detailed report of the crime with a feature questioning the public’s morbid curiosity:

The Citizen reported that a man Coles had been with earlier in the day, James Thomas Sadler, was arrested for the crime, leading to speculation that the Ripper had finally been apprehended. However, Sadler was eventually released due to lack of evidence, and optimism that the Ripper had been caught quickly dissipated. Investigations eventually separated the canonical five victims of 1888 from the other Whitechapel murders, while the true identity of the Ripper continued to be shrouded in myth and conjecture. It was theorised that he had left England, been imprisoned for another crime, or perhaps died. As time has passed, many have claimed to have solved the puzzle, but still no definitive perpetrator has been named. Now, 130 years on and with no living witnesses remaining, the possibility of unmasking the Ripper seems even more remote. Jack, it seems, is destined to remain a mystery; a legend both created and forever preserved by the press.

Julie Greenhill

Reading Room Team