Collecting and Collections Part I: The habits of the Satin Bowerbird

This is the first of a new mini-series of blogs which will explore different aspects of the theme of collecting and why collectors collect what they do. The James David Forbes Collecting Prize is open to any registered student of the University of St Andrews. The closing date for entries to this year’s prize is 1 July 2019.

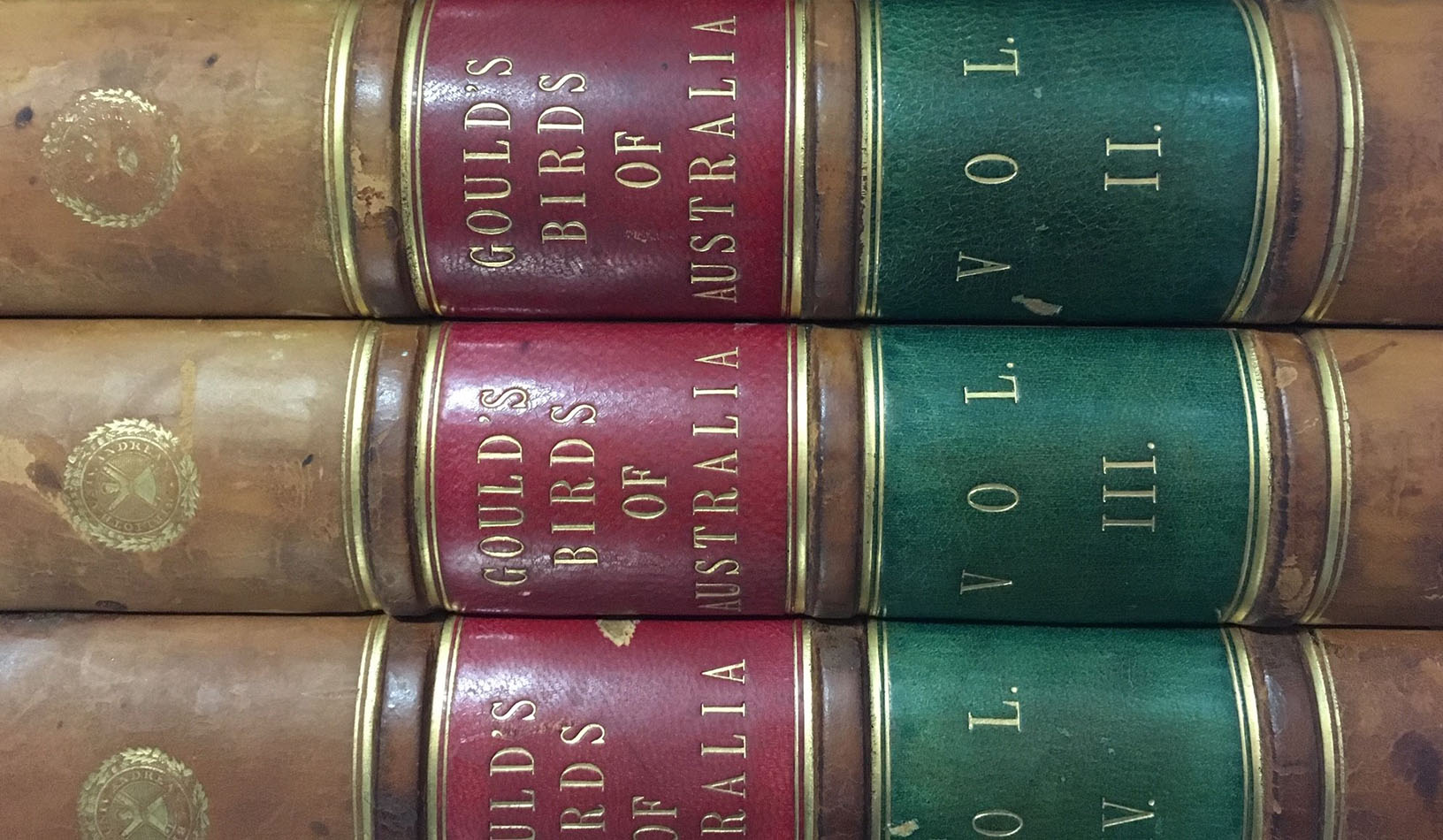

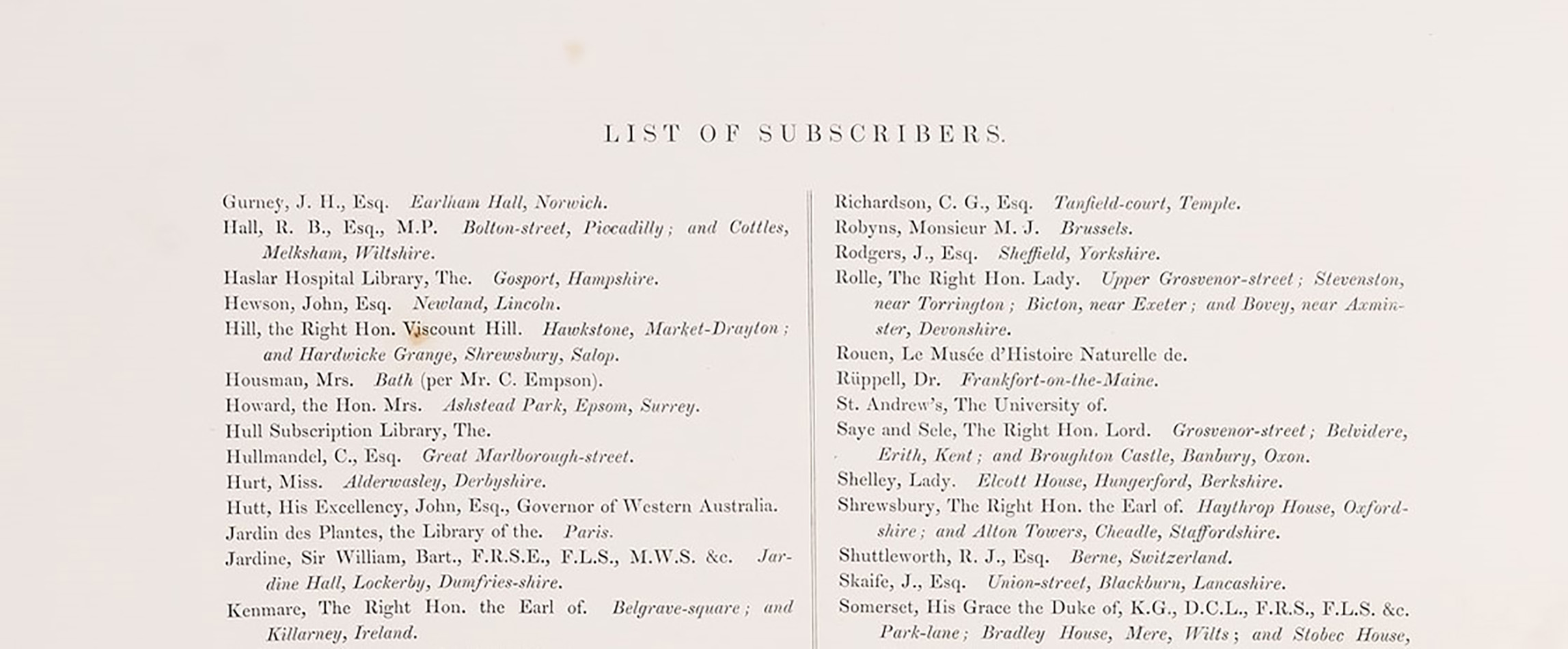

John Gould’s Birds of Australia would grace any library. The full set consists of seven huge folio volumes issued in parts between 1840 and 1848, plus the Supplement volume published between 1851 and 1869. Whenever we produce a volume of Gould for teaching or an outreach event, the spectacular hand-coloured lithographs draw gasps of admiration. We’re able to do this with The Birds of Australia because the University of St Andrews subscribed to the original publication, as shown in the List of Subscribers in the first volume, below.

Fundamentally, though, it is all about collecting. Gould and his colleagues collected specimens, facts, and field observations. Gould also had to collect subscribers to fund the enterprise. Institutional and individual subscribers, with multiple and perhaps irrecoverable motivations, decided to add the proposed publication to their collections. Then they had to wait, slowly collecting parts as they were issued, before binding them up into a splendid set of volumes. And this makes Gould’s Birds of Australia the perfect introduction to a new mini-series on this blog which will feature in the coming weeks, exploring different aspects of the theme of collecting and why collectors collect what they do.

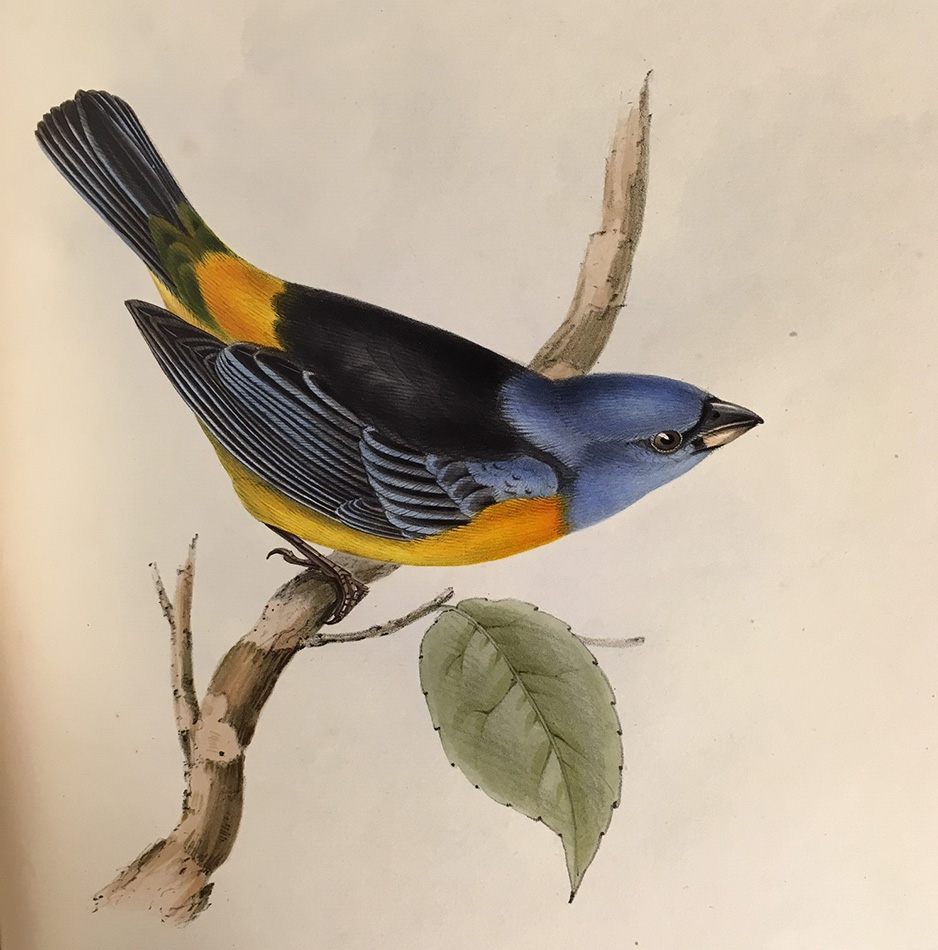

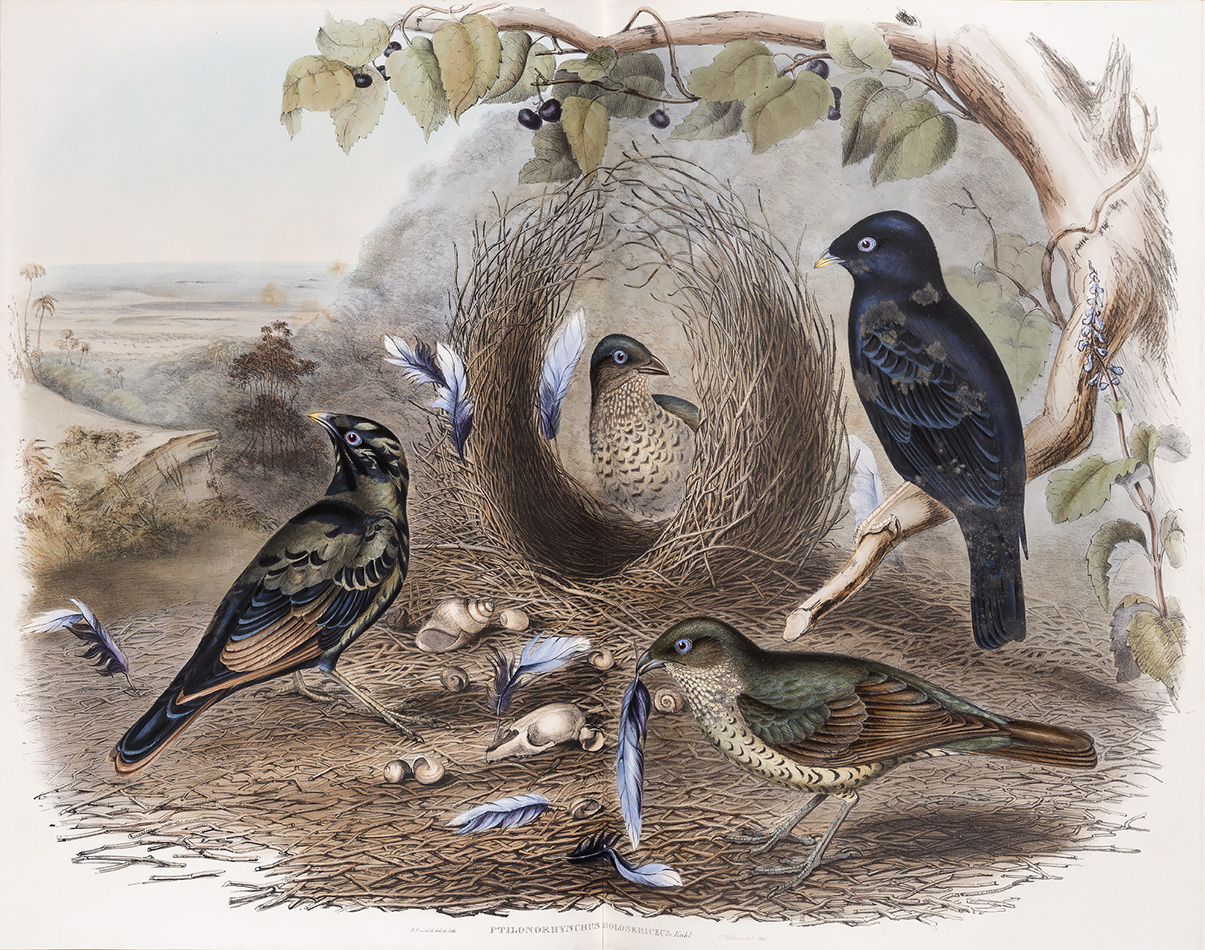

This is in some ways epitomised by one particular story in The Birds of Australia: the habits of the Satin Bowerbird (the modern binomial name is Ptilonorhynchus violaceus; Gould used Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus). These beautiful birds are found in eastern and south-eastern Australia, though Gould only observed them in New South Wales. He records that their habits had ‘never been brought before the scientific world’, and that it was ‘a source of high gratification to myself to be the first to place them on record’.

Gould was talking here mainly about the ‘extraordinary bower-like structure’ which male Satin bowerbirds construct out of interwoven sticks and twigs. He first encountered an example of the structure in the Australian Museum in Sydney, but was later able to observe the behaviour in the field. Gould drew attention to the fact that after building the bowers, the birds decorate them with collections of objects: he describes feathers, bones, snail-shells, rags, and human-made artefacts.

The interest of this curious bower is much enhanced by the manner in which it is decorated at and near the entrance with the most gaily-coloured articles that can be collected, such as the blue tail-feathers of the Rose-hill and Pennantian Parrots, bleached bones, the shells of snails, &c.; some of the feathers are stuck in among the twigs, while others with the bones and shells are strewed about near the entrances. The propensity of these birds to pick up and fly off with any attractive object, is so well known to the natives, that they always search the runs for any small missing article, as the bowl of a pipe, &c., that may have been accidentally dropped in the brush. I myself found at the entrance of one of them a small neatly-worked stone tomahawk, of an inch and a half in length, together with some slips of blue-cotton rags, which the birds had doubtless picked up at a deserted encampment of the natives.”

More recently, the birds have been observed collecting plastic straws, bottle caps, and plastic debris, which have become increasingly available through urban growth.

Gould recorded his observation without being able fully to explain the behaviour he had observed. Scientific literature now recognises the place of this behaviour in the bird’s complex courtship rituals, as the females’ mate choice is influenced by well-constructed and highly-decorated bowers. The males have been shown to practise deliberate selection in assembling their collections of bower decorations, and will remove objects placed in their displays that do not meet their collecting parameters (for example, red objects). The females compare the size and construction of the bowers and scrutinise the number, type, and quality of the bower decorations, before soliciting the male of their choice. A further elaboration of the courtship behaviour established since Gould is that the male birds paint the bower-structures as well as displaying their collections. The bias towards the colour blue, which Gould noticed, has been the subject of considerable research and interest. What is fascinating to the non-ornithologist, however, is that this vignette is a description of a bird obsessively collecting objects, by a man who was himself an obsessive collector, which was documented and illustrated in a publication that is highly desirable and collectable, and which is itself an object of obsession for some collectors.

For book collectors, the quality of their collections will not (usually!) determine mate choice. But it can be just as competitive an activity as bower-decorating. The student book collecting prizes at several universities across the UK encourage students to build their own coherent collections around a common theme. Here at St Andrews, the 2019 James David Forbes Collecting Prize is open for entries until 1 July. Registered students with the collecting instinct and the discrimination of a male Satin bowerbird are invited to submit their collections to the judging panel for scrutiny, with the prospect of a substantial reward.

Over the next few weeks we will be featuring a short series of blogposts exploring the idea of collecting and collections through examples such as albums of algae and seaweed, iconic engravings, and clutches of knitting patterns hidden in the Papers of an Eminent Scientist. The aim is to unpick what makes a collection as opposed to an accumulation of stuff, how collections have been put together, and what drives collecting behaviour. Above all, though, we want to celebrate collecting and all collectors, from Gould to Ptilonorhynchus violaceus.

Elizabeth Henderson

Rare Books Librarian

[…] the second part of the Collecting and Collections blog series, our Manuscripts Archivist takes a look at the trend of fern collecting, […]