Out of the ashes: framing the panel of reagents

Part of the Library’s Special Collections role in caring for its irreplaceable historic collections of rare books, photographs and archives is to develop and maintain an Emergency Response Plan. Our Emergency Response Plan includes the resources we need to recover and salvage our collections in the event of a major incident such as a fire.

The devastating effects of fire were recently witnessed internationally in news video footage of Notre-Dame cathedral which was ravaged by fire and suffered colossal damage as a result. Apart from the damaging effects to a building and its contents from fire and smoke, the deluge of water used to control and stop fire can be equally devastating. This was made all too real for colleagues in the University’s Biomedical Sciences Building after a fire on campus at the start of the year.

On the afternoon of Sunday the 10th February 2019 a fire broke out in the Biomedical Sciences Building burning through four rooms on the second and third floors and causing extensive water and smoke damage to other areas of the building and especially the lower floors where critical biological research materials were stored. Very fortunately there were no injuries or casualties in the incident.

The salvage process prioritized the retrieval and relocation of research material and priority personal items of staff and students. The building decontamination and recovery process is ongoing.

In this blog post, School of Biology Research Fellow Dan Young describes his experience of the incident and collaboration with the Library’s Special Collections paper conservator Erica Kotze ACR to mount and frame a salvaged item.

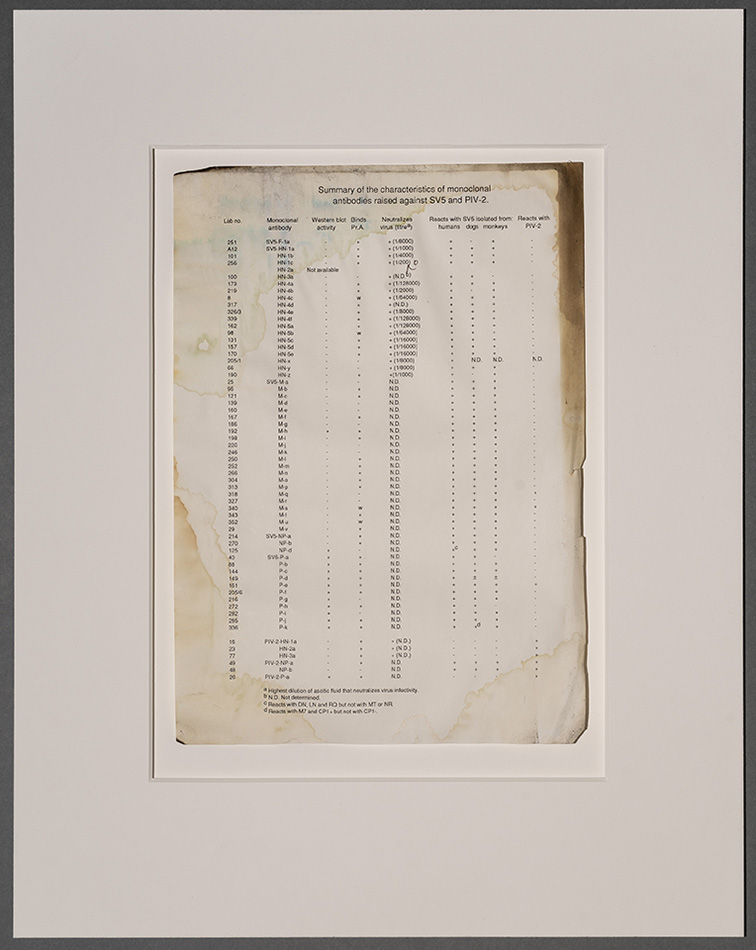

Fire catches you unawares. I felt pretty helpless watching footage of the fire’s progress through the Biomedical Sciences Building (BMS) building on February 10. My lab space was on the second floor of BMS, directly below the lab where the fire broke out. Initially I thought my bench might be spared as fire “should” spread upwards but alas, later footage showed a well-established blaze inside my window. Irreplaceable stocks of cells and viruses escaped damage and were retrieved in the first wave of rescue missions. Other precious, but more replaceable, reagents were lost to the fire. More of an unknown was the fate of data and information in paper form – I knew that I had several folders and lab-books on the top shelf right where I’d seen the fire raging. I was concerned for the whereabouts of a sheet of information on a panel of reagents made when I moved to St Andrews in 1985 – it related the trivial numbers we initially assigned to antibodies to the more logical names we gave them when publishing our work – our “Rosetta Stone” if you will. Most, but not all, of the information was written in a lab-book, likely to have been right in the fire’s path.

Retrieval of anything from such a situation is fraught with risks – the nature of any fumes and deposits from the burning of so many chemicals, some undoubtedly highly toxic, then there is the broken glass – not just from windows but also from countless reagent bottles and other items. There is also the risk of debris falling from the remains of burned and waterlogged, unstable ceilings. For the first few days, there was a steady pouring and dripping of water out of the building.

Those involved with initial scouting took photographs of the affected areas. My collection of folders/lab-books could be seen, still on their top shelf, albeit charred although I couldn’t see to what extent. Kitted out with protective gear and accompanied at all times, one of our excursions went to my bench, there was the very charred spine of that old lab-book – carefully removing it I could see that, having been tightly held in (and protected) by other folders, the pages inside were virtually untouched. Incredibly (to me), inside the lab-book, there was also an intact printed copy of the table of information which we would need in order to go back to our cryogenically frozen cell-lines to “grow” more antibodies.

That lab-book and piece of paper have no monetary value but the information they hold was invaluable. Having taken photographs the information is now preserved and I could simply discard the paper …. but why not preserve it, exactly as I found it – a bit scruffy with a hint of charring at the corners, brown where it hadn’t burnt but had been exposed to air/smoke/fumes and tide-marks from its encounters with water – for posterity, maybe even display it in the BMS building when it is eventually restored. Enter the Library’s Special Collections Division.

Erica picks up the story.

It is generally understood by those of us working with historic paper-based collections that items should not be stored too tightly on a shelf. Good practice for retrieving bound volumes from a shelf is to push the two adjacent volumes back, thereby exposing the spine of the item to be taken off the shelf; or to place your hand over the head of the volume and to push the volume towards yourself from its foredge. Both of these methods require some space for movement between the shelved books. Not so much that the books lean over, thereby damaging the end caps and joints, but enough so that they aren’t damaged mechanically during retrieval.

However, it was precisely because Dan’s lab-books and folders were so tightly packed on the shelf that they survived the fire, albeit with minor smoke and water damage! No cleaning or flattening treatment has been carried out to ‘the sheet of information on reagents’ salvaged from Dan’s lab-book, but it was framed to conservation standards.

The ‘reagents sheet’ has been window and back mounted in 4 ply, 100% cotton mount board using Japanese kozo paper (Usumino 28 gsm) and wheat starch paste. A spacer of archival E flute grey/white board has been added between the mounts to compensate for the cockling and planar distortion in ‘the sheet’ resulting from water damage. The glazing is museum grade acrylic with a UV filter. This ‘mount package’ has been sealed using an aluminised polyethylene film adhered onto the edges of the glazing and framed in an Oak frame.

Until Dan’s lab in the Biomedical Sciences Building is ready, the framed ‘sheet of information on reagents’ will hang in Dan’s temporary lab in the University of Dundee’s Wellcome Trust Centre.

Special Collections carries out regular training in disaster salvage and recovery after various scenarios. This year’s training will run in association with the Scotland group of the Institute of Conservation (ICON) and will be opened up to external professionals and members of the public. The course is a full day practical workshop, taking place on Wednesday 19th June, with an option to attending the morning lectures only.

For more information on the course, times and how to book see the Eventbrite page below: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/icon-scotland-group-salvage-of-library-archive-and-museum-collections-workshop-tickets-60919405582?aff=ebdssbdestsearch

Dan Young

Research Fellow, School of Biology

Erica Kotze ACR

Preventive Conservator