St Andrews Then and Now: A Rephotography Project: Part V

This is the last instalment in a series of five blog posts featuring juxtapositions of early photographs of St Andrews, selected from the Special Collections Division of the University Library, with the same views today. Published during the 2019 Photography Festival, this project aims to bridge 180 years of photographic history by inscribing these comparisons both within the context of their creation, and within the broader history of St Andrews. To view the juxtapositions, click on the illustrations.

North Street, United College & Market Street

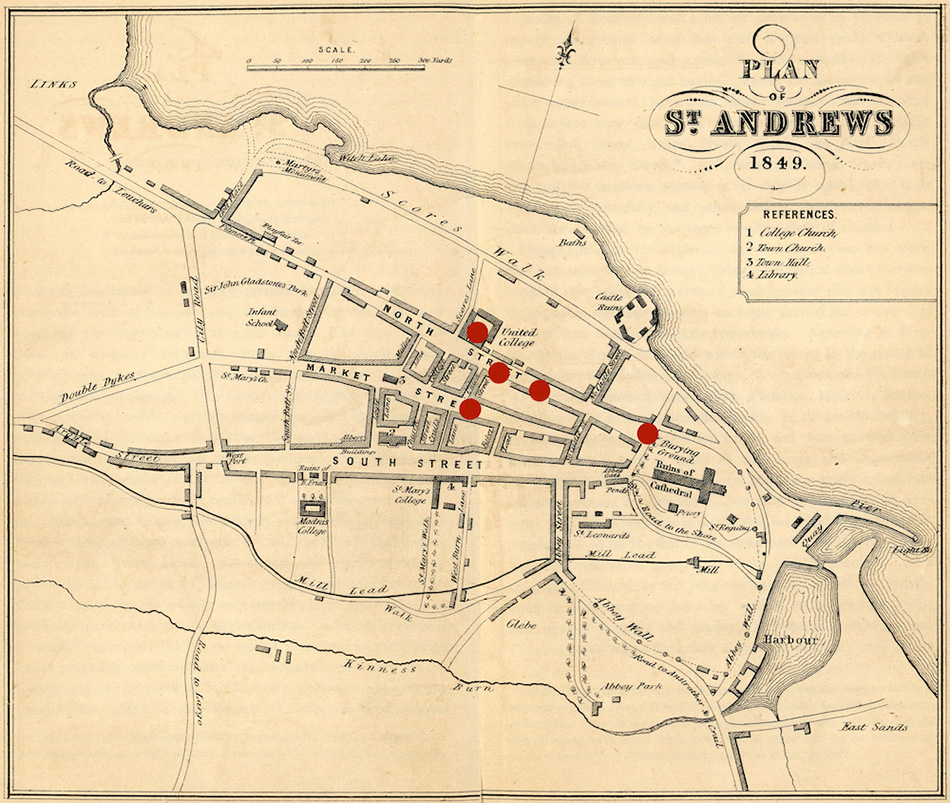

After having explored South Street, the Cathedral, the Pends, the Harbour and the Castle in previous blogs, this last post in our rephotography series will focus on the northern and central parts of the burgh.

There was a lay settlement adjacent to the ancient Pictish monastery of Kinrimund (Cennrígmonaid, first documented in 747) long before it grew to become a burgh as the town of St Andrew in the mid-twelfth century. At the time of the granting of the royal charter in the reign of King Malcolm IV (r. 1153-65), two axes of circulation were designed to converge on the shrine of St Andrew from the west: North Street and South Street.

Anonymous, North Street, St Andrews, salted paper print, 1842. ID: ALB-2-199.

This anonymous photograph was taken from the east end of North Street, between the castle and the cathedral. This is where the first lay settlement was situated, and where the local fishing community would remain for centuries. Although both castle and cathedral were left to decay after the Reformation, fisherfolk were still living in the area into the nineteenth century.

The first organised market in St Andrews stood at the junction between North Street and Castle Street visible in the picture. It was moved to what is now Market Street in the 1190s. Most of the houses lined up on the right side of the frame up to North Castle Street still stand. Dominating the composition in the distance is the tower of the chapel of St Salvator’s College, founded in 1450.

The earliest in our series, this photograph cannot be attributed with certainty. According to various sources it may have been made in the early 1840s either by Sir David Brewster, then principal of the United College, Colonel Hugh Lyon Playfair, the town’s Provost from 1842 to 1861, or Dr John Adamson. All three were leading pioneer photographers in St Andrews.

Let us now move west, towards the heart of the University.

Anonymous, North Street, St Andrews, albumen print, 1860. ID: ALB-10-21.

This unattributed picture bears witness to the state of North Street around 1860. The image is much sharper than the other photographs in this post, all salted paper prints made after calotype negatives. Their characteristic pictorial haziness is caused by the fibres of the paper, in which the photosensitive compound is absorbed both at the negative and at the printing stage.

To the contrary, this photograph of North Street is an albumen print made after a collodion glass plate negative. In these processes, the photosensitive compounds are always evenly distributed, first in an emulsion of wet collodion coated on glass, second on a smooth layer of dried albumen applied on the paper beforehand. In addition, the wet plate process is much quicker than the calotype, which facilitates the depiction of moving objects such as the human silhouettes that animate this composition.

By 1860, North Street had undergone considerable transformations under Hugh Playfair’s tenure as Provost, including the addition of a pavement on each side. To the right can be seen the Episcopal Chapel, built in 1825 in the Gothic Revival style and now replaced by the College Gate building. When this composition was framed, its minister was the Reverend Charles Jobson Lyon, who wrote two books about the history of St Andrews. The congregation outgrew the building in the 1860s and the chapel was sold to the Free Church congregation in Buckhaven. The building was dismantled and the stones were transported by sea to Buckhaven where it was rebuilt. The congregation moved to the larger Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Church at the bottom of Queens Terrace, which was consecrated in 1869.

Another church can just be seen to the left edge of the original composition. Now a research library for postgraduate students and the home of the Special Collections Napier Reading Room, Martyrs Kirk was completed in 1844 for the parishioners of the newly founded Free Church of Scotland. The continuous growth of the congregation required several campaigns of enlargement and refurbishment. Added in the 1850s, the spire visible in the original photograph was removed when the church was remodelled to its present form between 1926 and 1928.

Anonymous, St Salvators College Church, St Andrews, salted paper print, 1845. ID: ALB-6-137.

This unattributed photograph brings us closer to St Salvator’s Chapel, the architectural focus of the college founded by Bishop James Kennedy in 1450 and dedicated for worship in 1460. The French influence apparent in the chapel’s structure originated from Bishop Kennedy’s many connections to France. These also had an impact on Kennedy’s commission of a mace for his college from the French goldsmith Jean Mayelle in 1461.

After the Reformation, St Salvator’s Chapel was given over to lay purposes and used by the commissary court, only to be brought back to ecclesiastical in 1761. Visible in the previous photograph but absent from this composition, the clock and the parapet at the base of the spire were only added in about 1851, after major rebuilding of the college including the addition of the present cloister to the north. Further transformations were carried out in the 1860s, when tracery was added to the windows. Another major refurbishment project took place in the 1930s.

When this exposure was framed, the chapel served as the parish church of St Leonard’s, and would continue to do so until 1904. The surroundings of the church have greatly evolved since 1845. Apart from the obvious invasion of motorised vehicles and the modernisation of public lighting, a monumental tree has grown next to the chapel, partially obscuring its nave and the adjacent building at 71 North Street, which now houses the University’s Department of Social Anthropology. This building used to be home to the College Hebdomadar before housing the University’s administrative offices prior to the building of College Gate.

Let us now pass through the barrel-vaulted gateway at the base of the tower, and enter the college quadrangle.

David O. Hill & Robert Adamson, The North wing of United College from the Southwest, salted paper print, 1846. ID: ALB-66-5.

The group of scholars and masters which was eventually incorporated as the University of St Andrews was already in existence by 1410. In the following year Bishop Henry Wardlaw issued a charter of incorporation and granted them privileges. Supported by James I (r. 1406-37), Wardlaw also soon petitioned Pope Benedict XIII for official recognition of the group as a university. Papal bulls confirming university status were issued in 1413, finally reaching St Andrews in 1414.

St Salvator’s College was second only to St John’s College, endowed in 1419 by Robert of Montrose and led by Lawrence of Lindores. With three colleges by the mid-sixteenth century, the University was quick to thrive. But the troubled days of the Reformation inaugurated a period of slow decline, which eventually led to the fusion of St Salvator’s and St Leonard’s College (created in 1512) in 1747, forming the United College.

Sixty years later, despite the fact that the north wing, as shown, had been rebuilt between 1754 and 1757, Royal Commissioners appointed to examine the state of the universities of Scotland deemed the United College to be ruinous beyond repair. Plans were ordered from Robert Reid, the King’s architect for Scotland, to replace it with a grander, more modern structure.

The Lords of the Treasury granted £23,500 for the construction. The east wing was torn down, and a new structure built in the Jacobean Revival style was completed in 1831, comprising one central section housing the stairwell, flanked by three bays on either side. However, the remains of the grant were then recalled to support the rebuilding of Marischal College, in Aberdeen, and construction was halted.

It was only in 1844 that a new grant of £6000 was agreed upon by the Government and sanctioned in Parliament to complete the new design for the United College. Hill & Adamson probably framed this exposure shortly before the old north wing was torn down. The north edge of the new east wing can barely be glimpsed by the right edge of the frame, but I decided to enlarge the composition to the right for the sake of clarity.

According to Charles Roger, the north wing was fitted with four classrooms on the ground floor and the upper two stories accommodated the students. Outside of the frame to the left was the mediaeval west wing, along Butts Wynd, also photographed by Hill & Adamson before it was demolished as far as the present Hebdomadar’s block.

Designed by William Nixon, the new north wing adopted the same Jacobean style as the east but a keen eye can easily spot the architectural differences between the two. Both wings were fitted with four classrooms. The north wing also accommodated a Great Hall and two museums (the Anatomical Museum and the Museum of the Literary and Philosophical Society). The present quad was completed in 1904-6 with an extension to Reid’s East building southwards by local architects Gillespie and Scott, in the same style as Reid’s work.

Let us now go back south through the tower and down College Street to examine the last view in our series of rephotographs of St Andrews.

Dr John Adamson, St Andrews. Town Hall, Market Street, salted paper print, 1845. ID: ALB-6-46.

Framed by John Adamson around 1845, this composition shows a view of Market Street from the east. The only buildings that remain unchanged are the last visible house at the northeast corner with Greyfriars Gardens, and the old Stewart Hotel (renamed the Cross Keys Hotel in 1858, now 85 Market Street), of which only a very narrow part is visible in my rephotograph.

The elephant in the room in this comparison is the tolbooth, the town hall that used to stand in the middle of Market Street. The centre of civic government, it also had a toll-collecting office and a gaol. The tolbooth was built in the twelfth century to the east of where the weekly market was held. In the Middle Ages a market cross stood at the centre of the square, symbolizing the king’s protection over those trading there. The square also played host to the Seinzie fair every April for two weeks, drawing traders from all over the country.

Adamson’s photograph bears witness to the state of the tolbooth after the sixteenth century, when it was almost entirely rebuilt. In the mid-nineteenth century, according to Charles Roger, and despite its historical importance for the town, it was ‘felt as an obstruction and regarded as a deformity’. Provost Playfair wished to do away with it and it was eventually torn down in 1862. The site of the building is now marked out on the cobbles of the street and the Whyte-Melville memorial fountain was erected further to the east in 1880.

Considering how much the scene has changed in the past 170 years, this was the most difficult picture to rephotograph. The juxtaposition is rather approximate but it seemed right to end this project at the social and commercial heart of St Andrews. I hope that this series of blogs has proved both informative and entertaining, and I thank all readers for their interest in the project.

Édouard de Saint-Ours

PhD candidate, University of St Andrews,

Université Le Havre-Normandie

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Rachel Nordstrom for her continued support throughout this project and her precious advice. My gratitude also goes to Alex Cohen, who generously gave some of his own time to proofread this post, and to Rachel Hart, who readily shared her extensive knowledge of the history of the university.

Bibliography

Brown, Michael and Katie Stevenson, eds. Medieval St Andrews: Church, Cult, City. Woodridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2017.

Crawford, Robert. The Beginning and the End of the World: St Andrews, Scandal, and the Birth of Photography. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2011.

Grierson, James. Delineations of St Andrews. Edinburgh: Peter Hill; St Andrews: P. Bowler; London: Vernor, Hood, and Sharpe, 1807.

Lyon, Charles Jobson. The History of St Andrews, Ancient and Modern. Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Printing and Publishing Co.; St Andrews: M. Wilson; Cupar: G. S. Tullis, and Gardiner and Anderson; Kirkcaldy: J. Cumming, and J. Birrell; Dundee: F. Shaw, and J. Chalmers; Perth: J. Dewar; Arbroath: P. Wilson; Montrose: J. and D. Nichol, and Smith and Co.; Aberdeen: Brown and Co.; London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1838.

Morrison-Low, A. D. ‘Dr John Adamson and Thomas Rodger: Amateur and Professional Photography in Nineteenth-Century St Andrews’. In Photography 1900: the Edinburgh Symposium, edited by Julie Lawson, Ray McKenzie and A. D. Morrison-Low, 19-37. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 1994.

Morrison-Low, A. D. ‘Brewster, Talbot and the Adamsons: The Arrival of Photography in St Andrews’. History of Photography 25, no. 2 (2001): 130-41.

Ordnance Survey. ‘Fife, Sheet 12’. Six-inch to the mile. Scotland, 1843-1882. Southampton: Ordnance Survey, 1855. https://maps.nls.uk/view/74426829

Roger, Charles. History of St. Andrews. Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black, 1849.

Stevenson, Sara and A. D. Morrison-Low. Scottish Photography: The First Thirty Years. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Limited-Publishing, 2015.