52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations, Week 3: An Evolutionary History of Photography

As part of our 52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations we will explore the Photographic Collection by examining the evolution of photographic processes as they are represented by our holdings. The aim is to underline the physical qualities of different photographic media and the cultural and commercial implications of advancements to these processes. The reader will be introduced to a medium first driven by the curiosity of science and then very quickly taken over by commercial imperatives. Although much attention in specialist texts about photography emphasise the “art” of photography and the aesthetics of unique prints, the creation of photographs, proportionally speaking, takes place far from artists, museums or art historians. Photography, for the most part, is a commercially driven medium. Although our Photographic Collection features fine examples of rare vintage material which has been identified as art, it is rather the scope and multiplicity of the subjects represented and how their communication and dissemination is shaped by specific photographic media which will be the driving theme behind these Photographic Collection posts.

—

Photography’s invention was not the result of chance or spontaneous scientific inspiration, but rather the culmination of a cultural need for an effective medium to communicate and disseminate visual information. An initial investigation into the history of photography reveals texts which make reference to the almost simultaneous invention of the medium in 1839 by both the Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), and the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877). This convergence of invention is arguably tied to an underlying cultural imperative, but beyond this there is the larger narrative of photography’s genesis. Digging deeper, one appreciates that there are many facets and interpretations to the history of photography’s invention and that indeed this was one embroiled not only in science but also in politics, business and class over a considerably longer period than previously thought. Key figures to investigate when interested in a more complete history are Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833), Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805), Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862), Dominique François Jean Arago (1786-1853), Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) and Hippolyte Bayard (1807-1887) but to name a few.

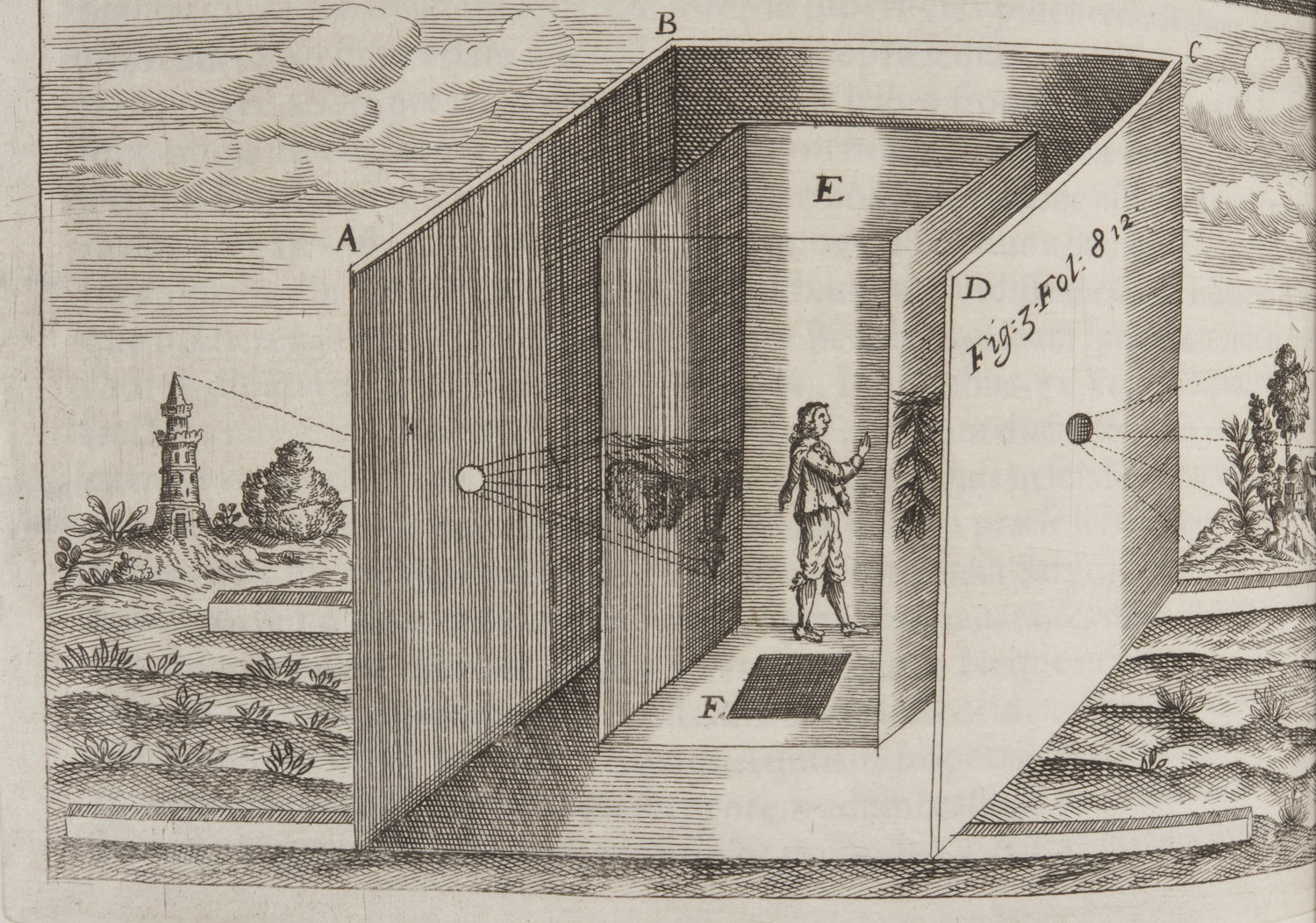

The notion of the illustrative powers of images formed by light and the desire to harness these is by no means a 19th century creation. From the shadows on Plato’s Cave to the optical devices of the renaissance allowing artists to represent the visual truth of perspective, to the moment on the shore of Lake Como when Fox Talbot, despite the aid of a camera lucida, was unable to author a worthy drawing, scientists, artists, opticians, philosophers and others have all attempted to interpret, codify and record the natural world as it is represented by the grace of light.

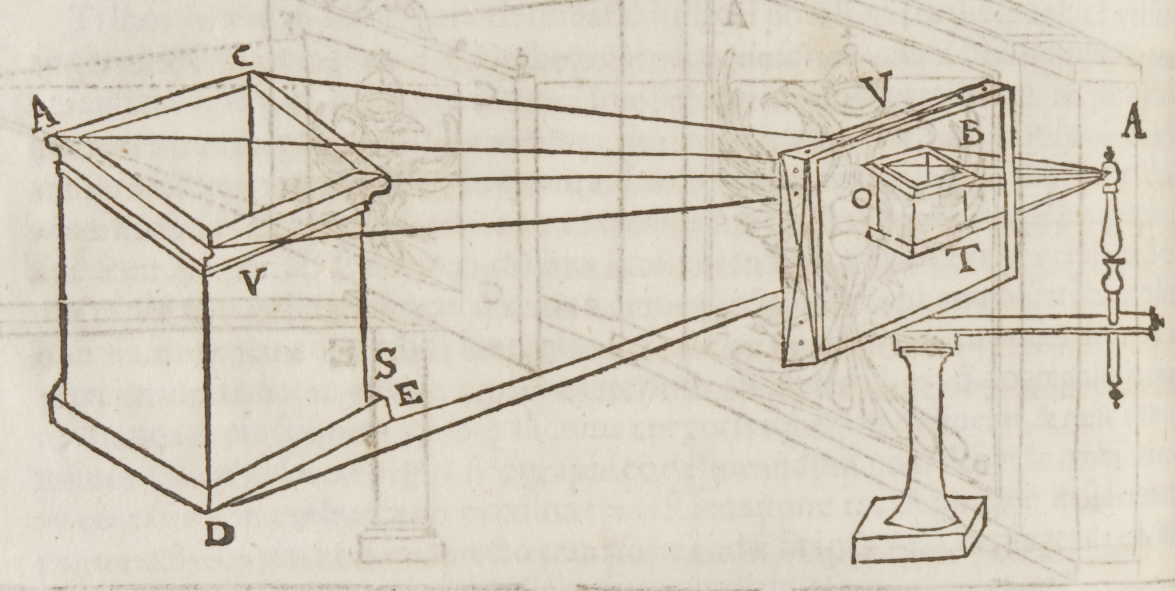

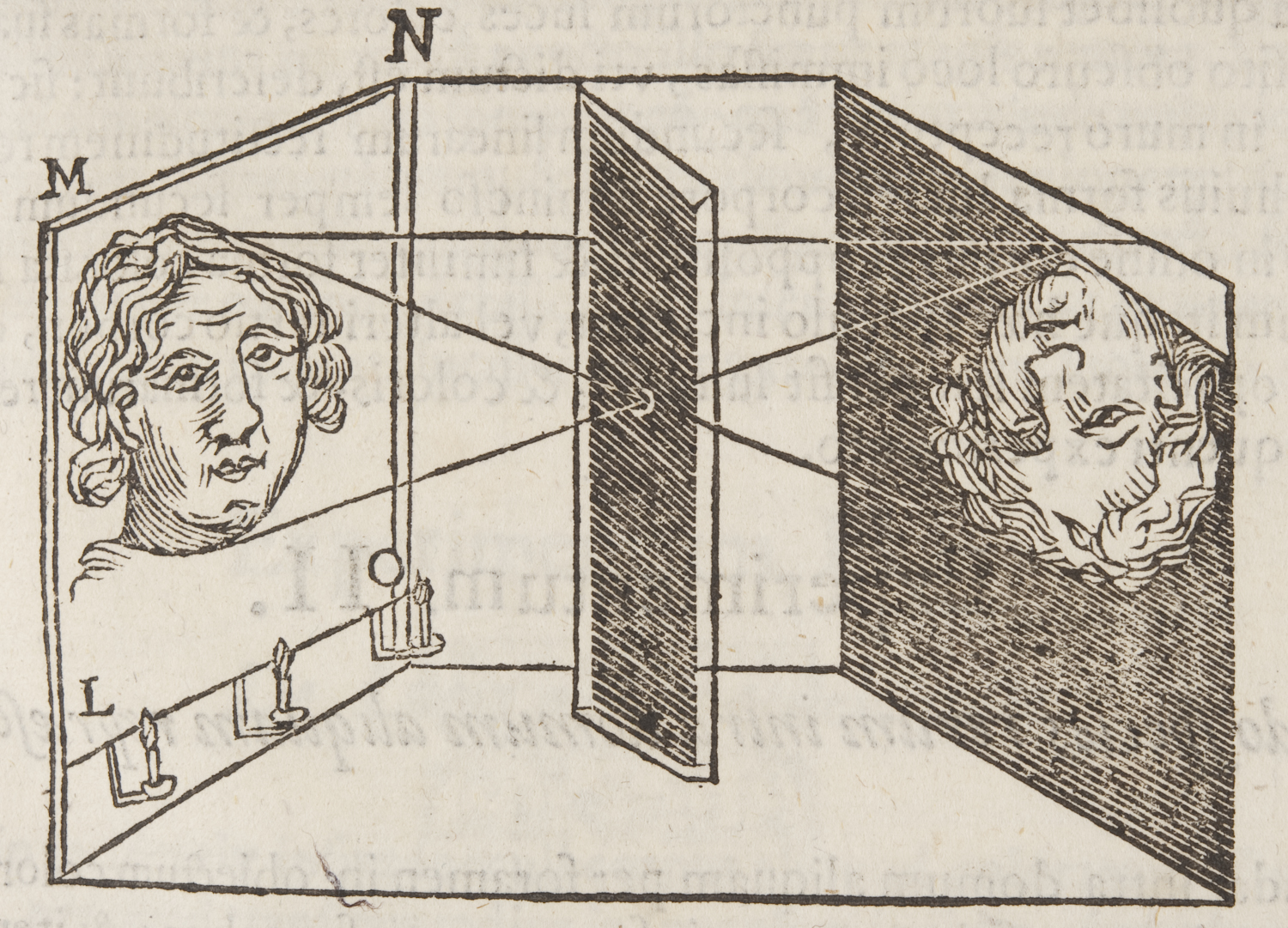

The Latin word camera obscura translates to “darkroom”, and describes the box or room in which an image projects itself onto an adjacent surface through an aperture or optical lens. Although the camera obscura is often seen as an 17th and 18th century artist’s aid, the driving principles of the device in fact predate the common era. In the 19th century it was these box-shaped devices which would be adopted by scientists and inventors to create the first photographic cameras.

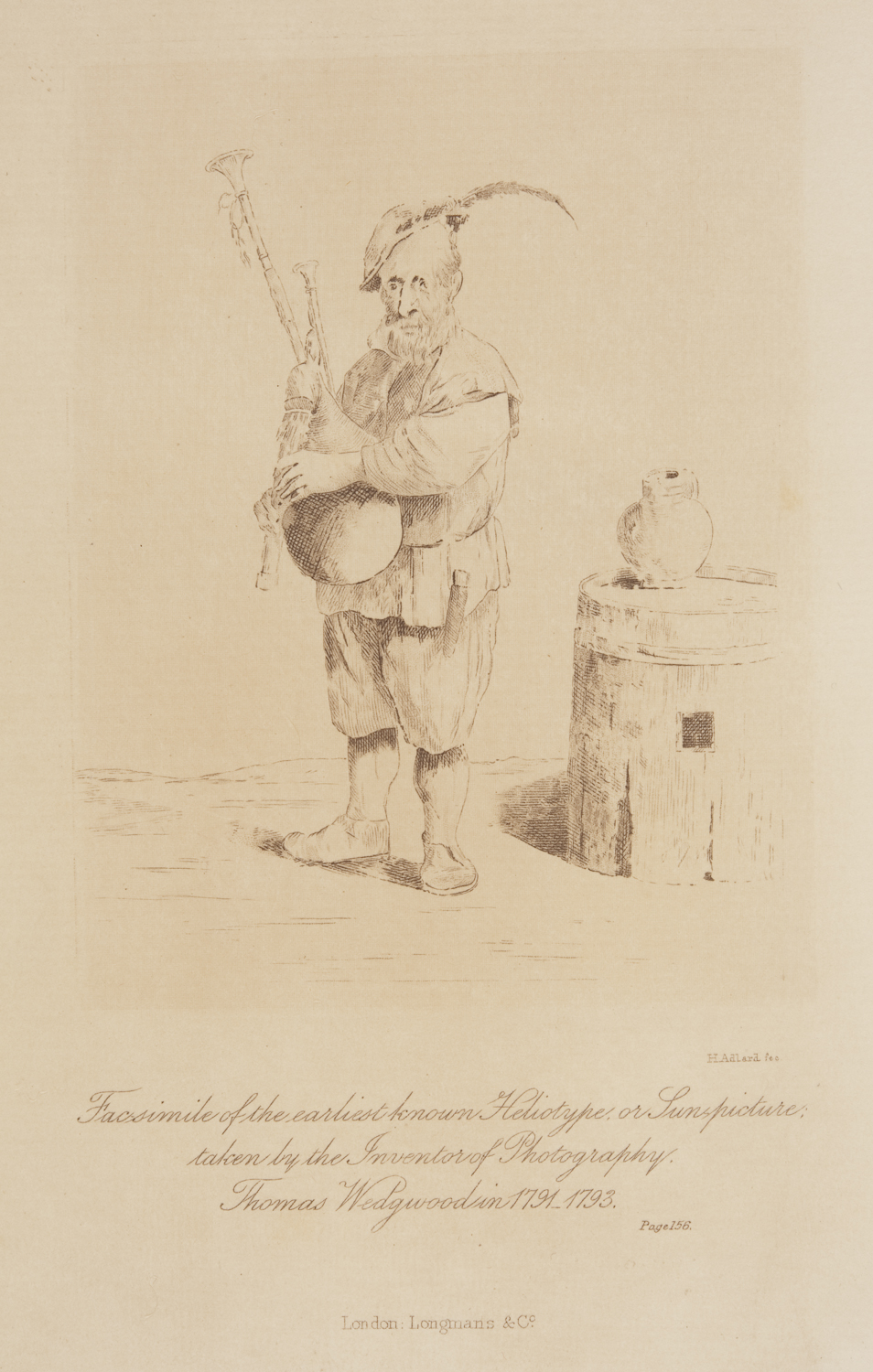

There are two specific “photographic objects” in our collection which tantalisingly suggest alternative, more complex histories of the medium. First is the frontispiece of a book entitled A Group of Englishman by Eliza Meteyard which is boldly captioned “Facsimilie of the earliest known Heliotype or Sun Picture taken by the Inventor of Photography Thomas Wedgwood in 1791-1793” underlining that photography had been discovered a full 48 years ahead of Daguerre and Talbot. According to correspondence from Talbot dated the 30th January 1839, although Wedgwood and Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829) had managed to create photographic images, they had not yet devised a means of “fixing” them or making them permanent. This book, articles outlining Wedgwood’s process published in London and Edinburgh in 1802, and also the astounding discovery in 2008 by Sotheby’s auction house of images of leaves (seemingly by Talbot) being attributed to Wedgwood, all point to our need to acknowledge the broader history of photography.

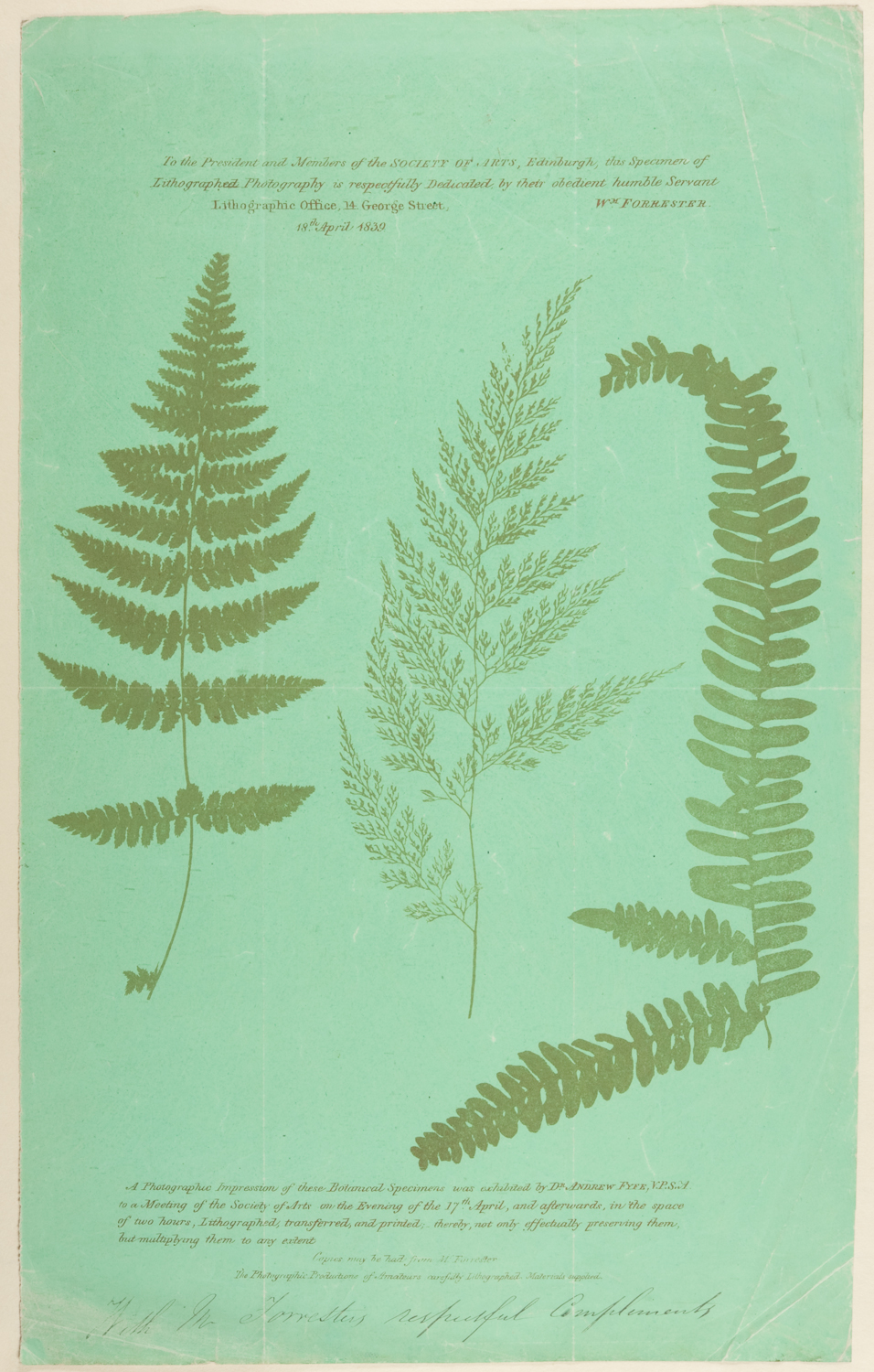

The second is a curious “photo-lithograph” by William Forrester of the Society of Arts in Edinburgh dated 18th of April 1839. This remarkable print was being confidently promoted only three months after Talbot publicly announced his new “photogenic drawing” process at the Royal Institution (25 January 1839). It remains an almost completely unknown process but is indicative of the 19th century desire to reproduce photographic images in the more permanent medium of the printer’s ink. St Andrews holds the only known copy of this process tying Scotland firmly to some of the earliest developments of photographic practice.

–Marc Boulay

Photographic Archivist

For an interesting insight into the Niepce-Daguerre partnership see http://www.speos.fr/index-speos-museum.html and follow the links on http://www.photography-museums.com/pagus/invus1.html

[…] In this case Robyn came to me with an idea in broad strokes – a camera obscura in a dark earth room – probably because she knows how much I like digging. But there are an […]

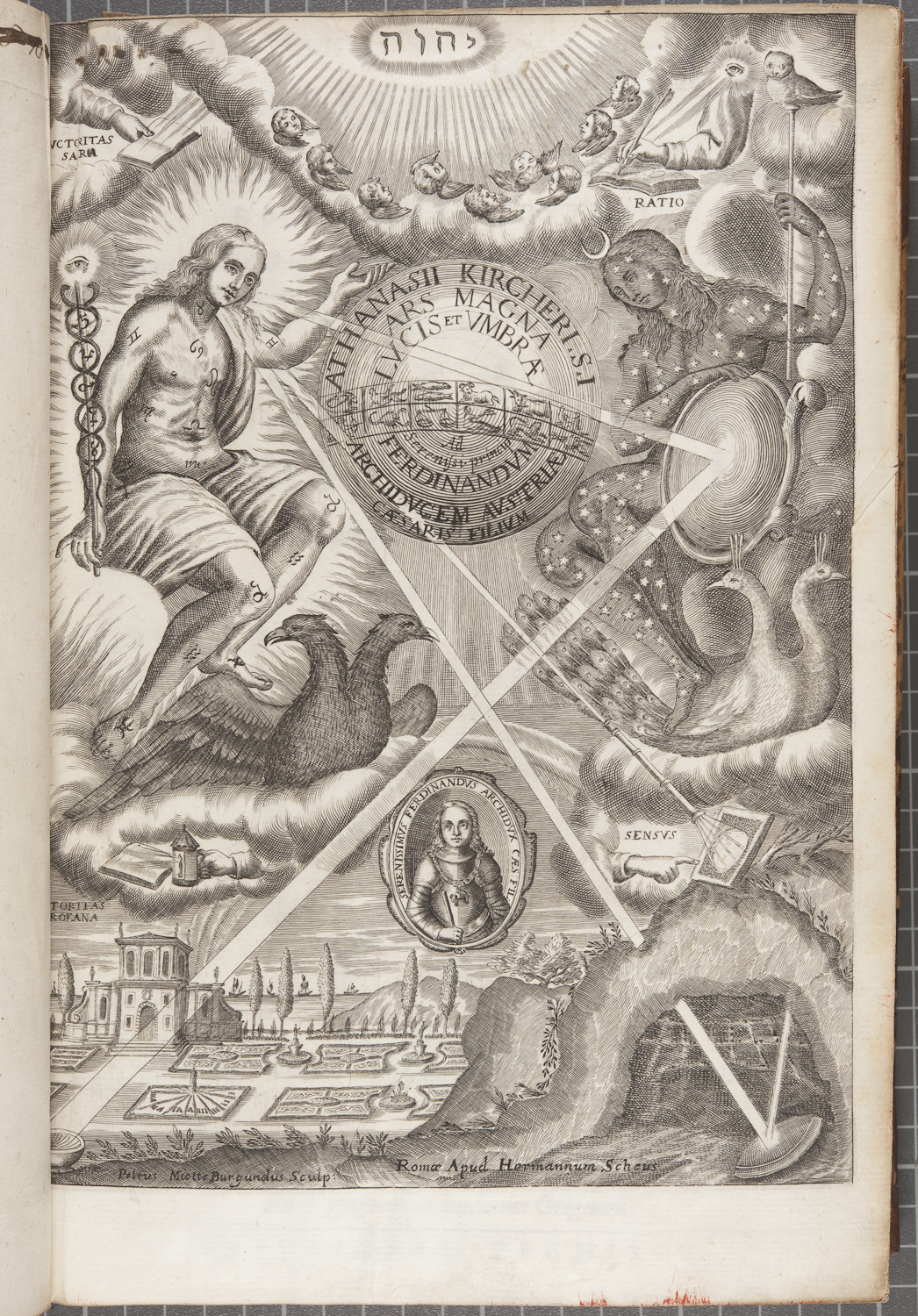

[…] et Umbrae (r17 QC17.K6C46), Special Collections of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland via standrewsrarebooks.wordpress.com. […]

Reblogged this on Eileen.