April Fools: FORGERIES, FAKES AND FALSEHOODS

In this week of April Fools pranks (or ‘hunting the gowks’ here in Scotland), I’ve been investigating forgeries, fakes and falsehoods in our collections and have come up with five stories: a forged signature, a forged bank note, fake testimonials, a fake degree certificate and even a false identity! Read on – these are all true!

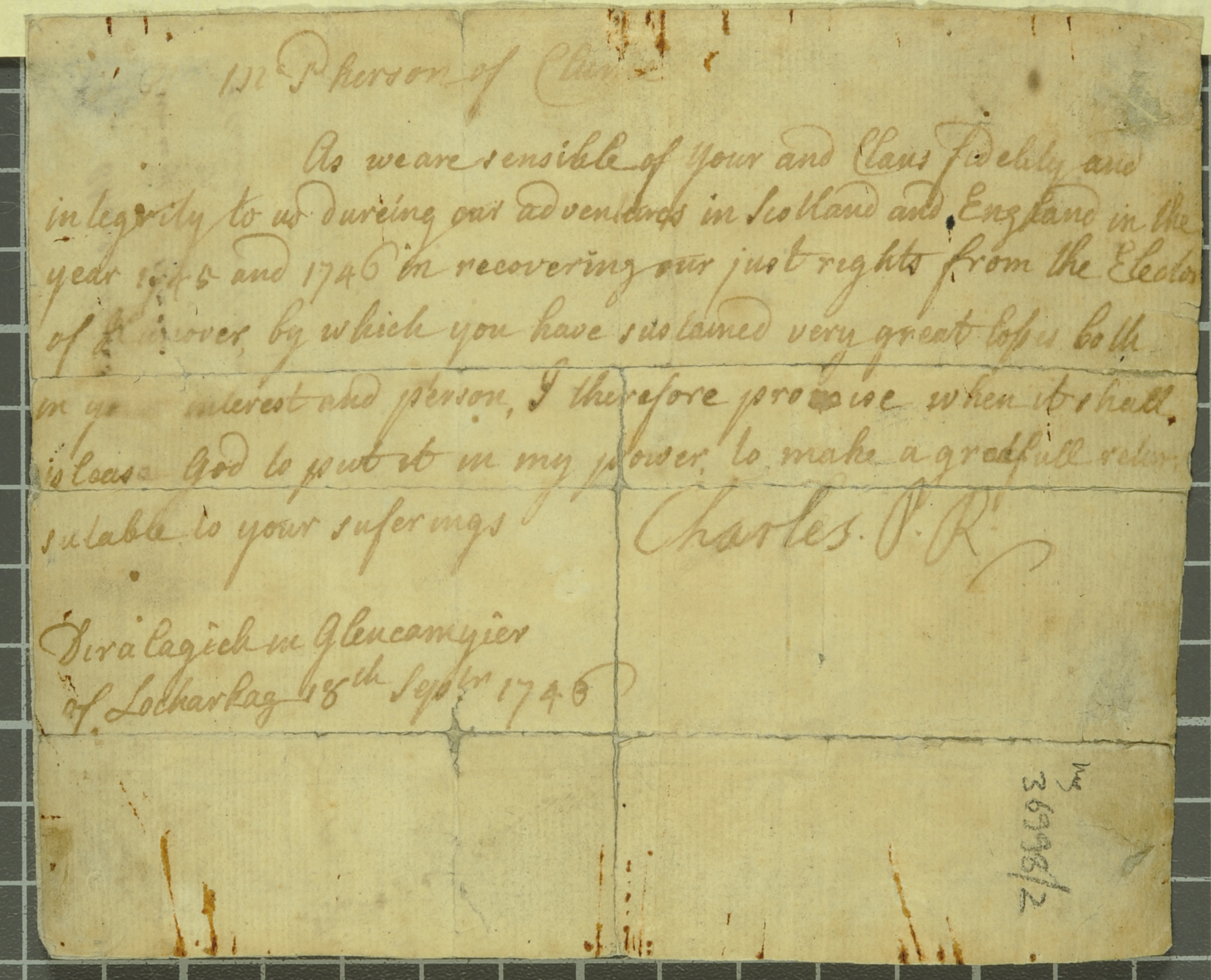

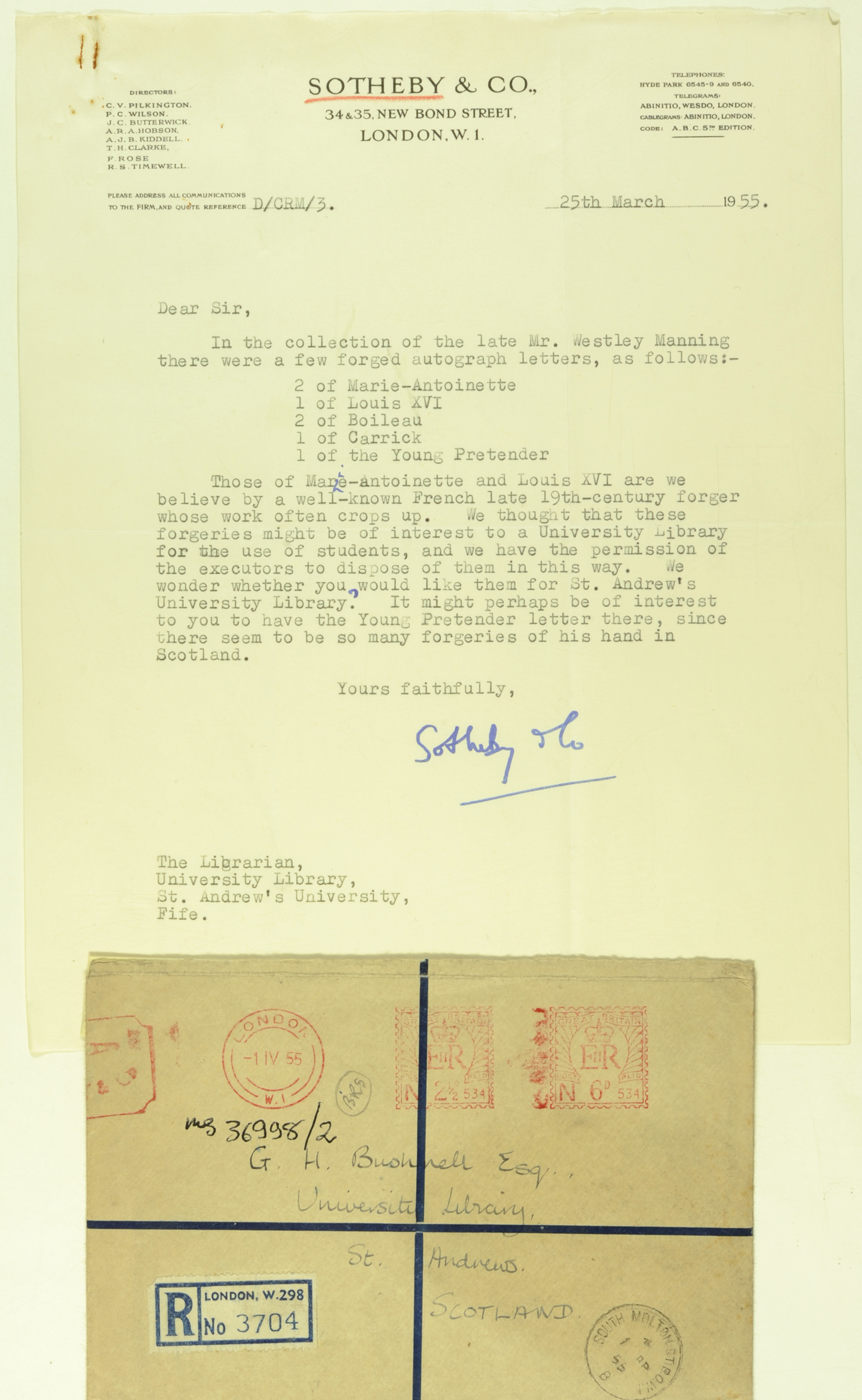

In March 1955 Sotheby’s Auction House offered the Librarian of St Andrews a known forgery to add to the collections: a letter of the Young Pretender, from the sale of a collection of forged autographs. Sotheby’s thought “it might perhaps be of interest to you to have the Young Pretender letter there, since there seem to be so many forgeries of his hand in Scotland.” This letter, dated 18 September 1746, just the day before Bonnie Prince Charlie sailed away from Scotland, is well known. The text appeared in print in a footnote to Sir Walter Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather (St Andrews copy at -sPR5322.T2.E70).

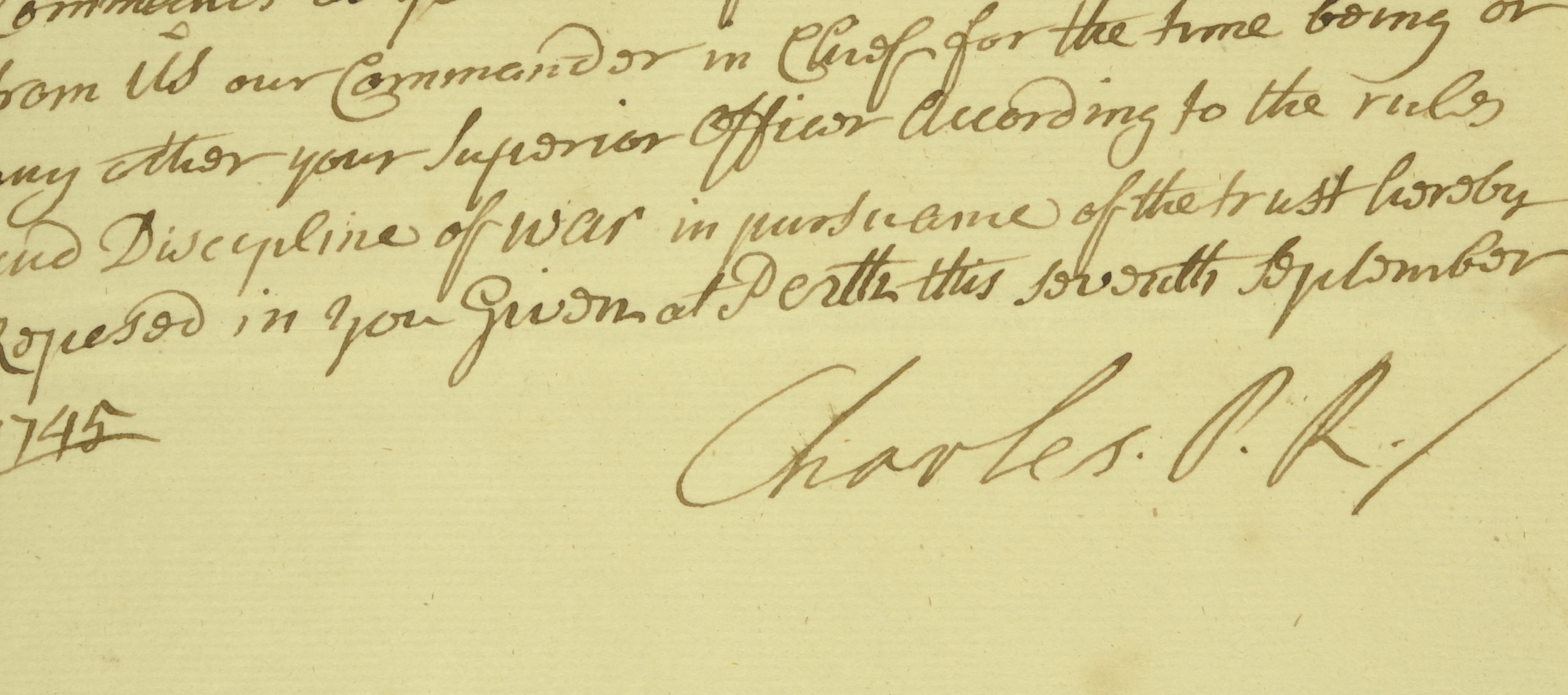

There is also an image at YourPhotoCard.com (with a rather dodgy transcription) where it is suggested that the original resides at Cluny Castle. I have not tried to verify the location of the original – perhaps someone might be able to confirm its whereabouts? In my attempt to check whether this signature (Charles P[rince]. R[egent]) was authentic, I looked for a genuine signature for comparison. This commission (above) of Charles Edward Stewart to an unknown recipient as a lieutenant in the regiment commanded by Euan McPherson of Clunie is dated 7 September 1745 and was bequeathed to our Library by Rev. John Stirton in 1944 (St Andrews msDA814.A5S8).

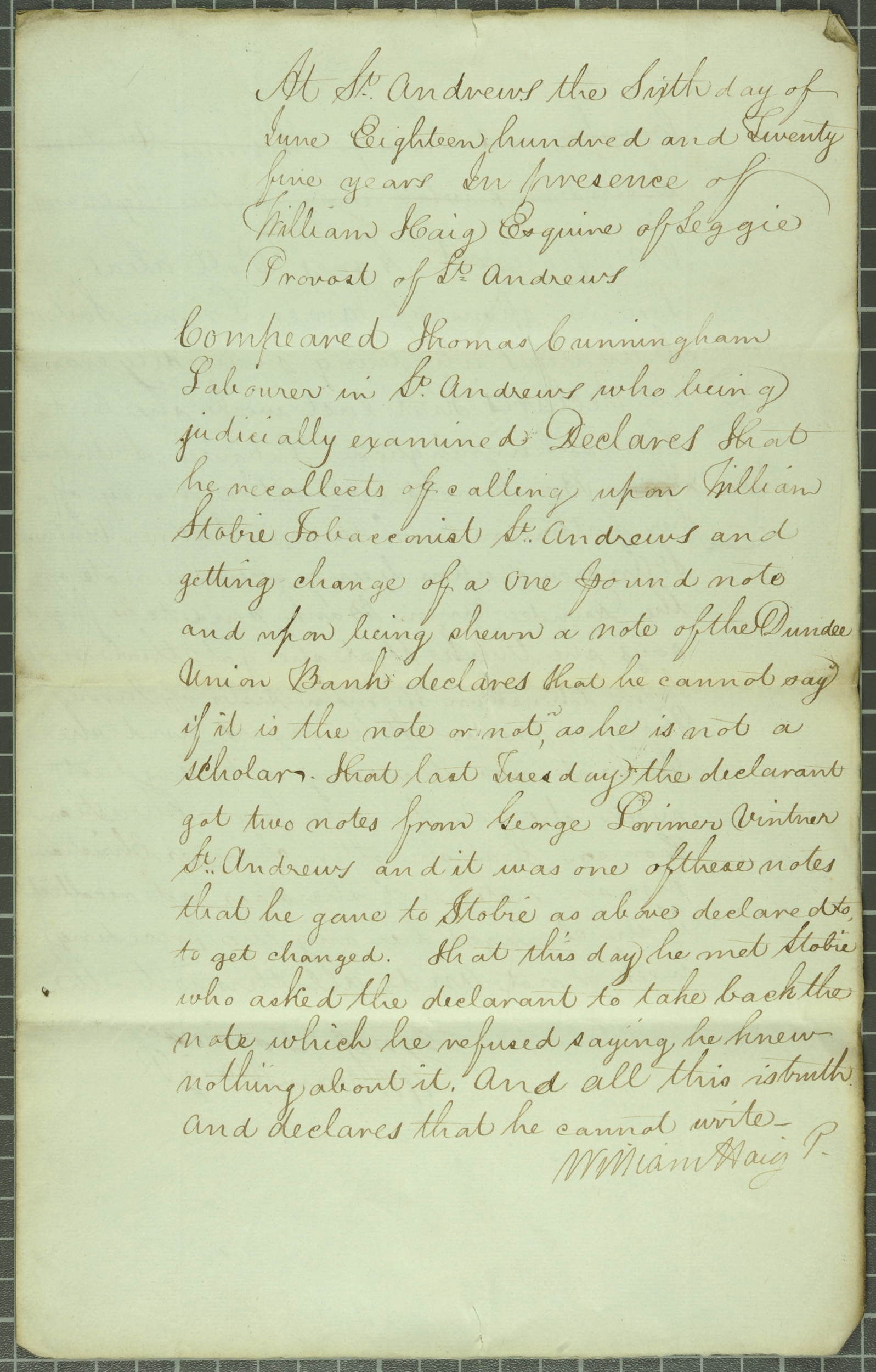

The story of the passing of a forged banknote in St Andrews in 1825 provides wonderful testimony to the fine detail which is carefully preserved within the on-file papers of the burgh. There are two statements of evidence gathered on 6 June against one Thomas Cunningham, illiterate labourer, who presented a forged £1 or twenty shilling note to William Stobie, tobacconist, and received change in silver (St Andrews B65/22/6/5/12). This banknote, dated 9 May 1823 and numbered 359/56 was drawn on the Dundee Union Bank. The passage of this note through various hands is carefully traced – Cunningham had got two notes from Agnes Dott alias Lorimer, wife of James Lorimer sailor, daughter-in-law of George Lorimer, vintner in St Andrews. She had in turn got it from Christian Thomson, sister of James Thomson, barber of St Andrews whose notes she often changed. After Stobie marked it, having suspected it was forged due to its pale colour, it was paid by his wife to Mr Joseph Cook, bookseller, who had it returned from the bank as a forgery. Cunningham used the fact that he couldn’t read as a reason for his knowing nothing at all about this matter and refusing to take it back. I was delighted to find that there is an image of an 1830s Dundee Union Bank £1 note on the British Museum’s highlights page, and that there is lots of information about the history of banknotes in Scotland here.

At a time when medical degrees were still awarded on the basis of testimonials as to the quality, qualification and character of practising Doctors of Medicine, two eminent practitioners would write to the university and vouch for the candidate for the degree. In 1815 the University Senatus (or governing body) uncovered a case where a doctor had supplied false testimonials in his own name and that of another doctor in support of a third party. Alexander Mundell, who was investigating the situation on behalf of the Senatus, spoke to the Bow Street Magistrates about the offence, and engaged in copious correspondence with Principal George Hill (St Andrews UYUY373). Ultimately, however, no prosecution was brought, as Senatus wished to conform to the wishes of the other doctor wrongly named in the testimonial. The doctor for whom the degree was sought, John Faithorne, was declared to be innocent of any wrongdoing and, in 1819, the University did indeed award him an MD on testimonials – from two different doctors! (St Andrews UYUY350/1819/F, right)

It wasn’t only testimonials that were forged. The Senatus in the early 1850s was alerted to the fact that there were false diplomas in circulation and took steps to remedy the situation. In 1852 the rather magnificent but entirely spurious MD diploma awarded to Samuel Laurence Gill (St Andrews UYUY348/D/2) was exhibited before Senatus and it was declared that “the same is not a genuine document, that it was never granted or issued by this University, that the pretended signatures of the granters of the said Diploma are not the signatures of any former or present Members of this University and that the Seal appended to the said alleged Diploma is not an impression of the Seal of this University.” And what action did they take? They wrote on the back of it a reference to the minute of that meeting of 14 February 1852 and kept it on file!

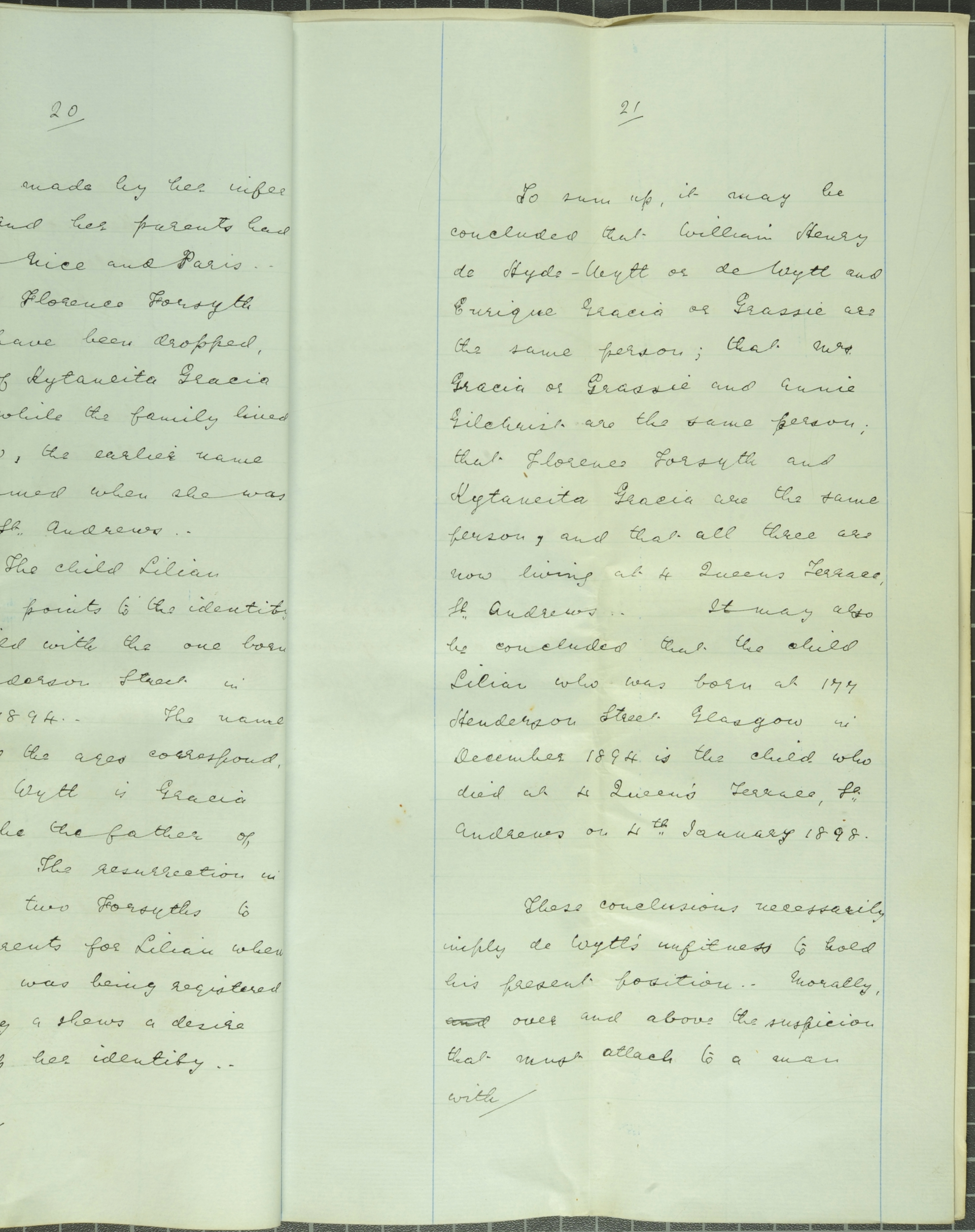

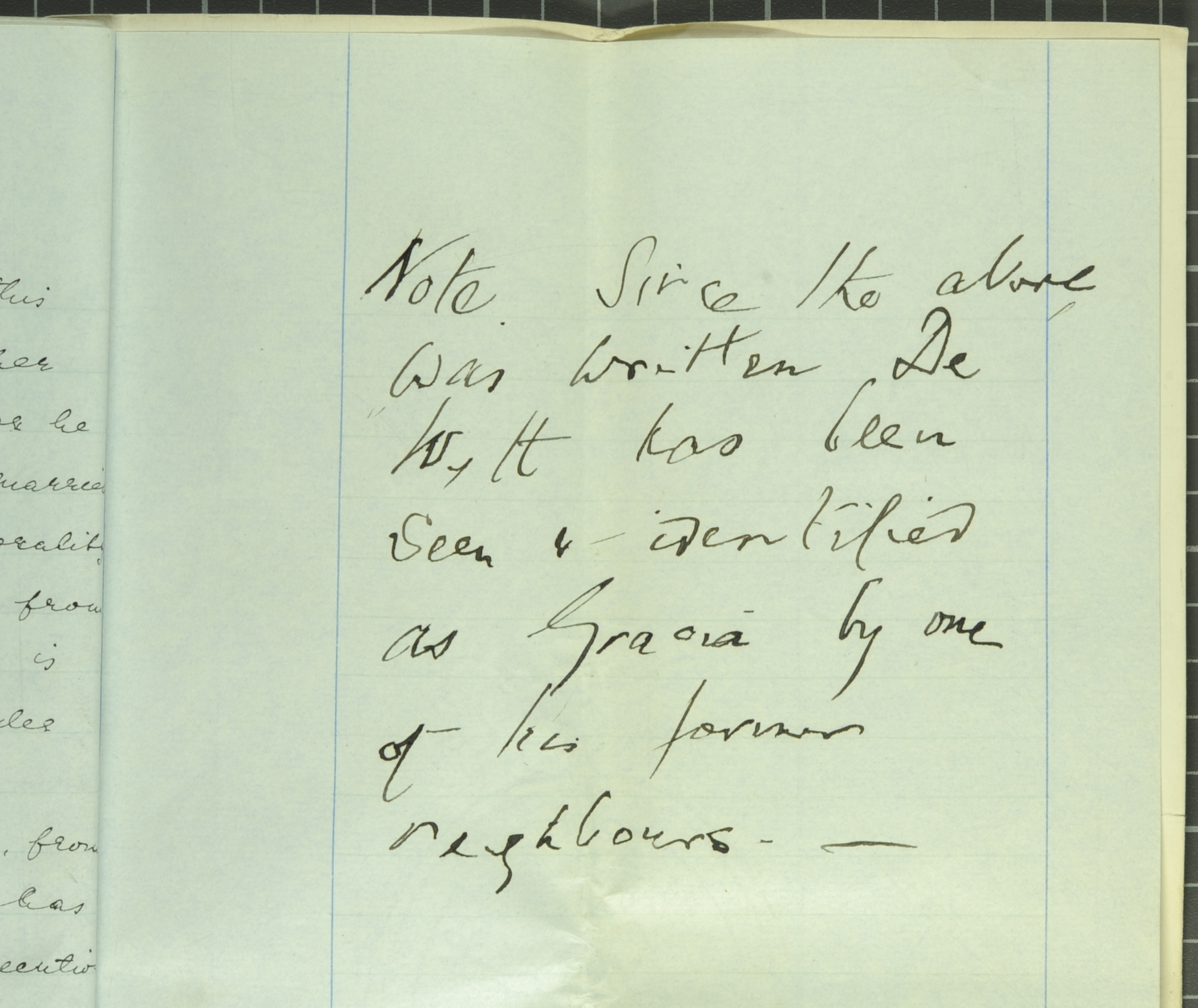

Finally, the story of Professor William Henry de Witt provides a fitting climax to this post. At a time when different factions were fighting for control of the University, de Witt was appointed as lecturer in Materia Medica (Pharmacology) by the supporters of the rector, the 3rd Marquess of Bute (left) in 1896. He held this post from August 1896 until October 1898 when he was elevated to the Chair of Materia Medica and Therapeutics through continued endorsement by Bute, who pressed his appointment in the teeth of opposition from Court and Senate. The Principals of the United College and St Mary’s College as well as Professors Herkless, Steggall and Burnett all registered their dissented. Inducted on 12 November, de Wytt’s tenure was shortlived, as within weeks he was called before the Senatus. A private detective’s investigation had revealed serious concerns. The report (St Andrews UYUY235/2/9) established that there was no record of the birth of any William Henry de Wytt. He was probably born as John Forsyth and was a law student in London before moving to take up medical studies at the University of Glasgow, from where he graduated MB CM in 1895.

He seems to have lived a double life as a student, giving a variety of places of birth and ages on his matriculation records, graduating aged 28 even though he had matriculated at the start of his studies aged 34! He used false addresses, including those of fellow medical students, where ‘the landladies knew him as calling for letters occasionally, and the mystery surrounding him gave rise to much curiosity and speculation.’ At the same time as being this medical student known as William Henry de Wytt, he lived a double life as Enrique Gracia, with a wife and child who lived elsewhere in the city. Indeed, the investigator uncovered a witness who saw the man she knew as Gracia (or Grassie) performing under the name of de Wytt in a student Gaudeamus. When he moved to St Andrews he lived at 4 Queens Terrace with a housekeeper and a teenager, both of whom were registered as students. They resembled in appearance the wife and child he had lived with in Glasgow. Most significant in 1898 was the fact that ‘he has laid himself open to persecution and conviction on the grave charge of falsifying the public registers’ in relation to the death of his younger daughter, Lilian. He registered her death in St Andrews on 4 January 1898 as both her guardian and the medical officer certifying her death, but gave her parents as George Forsyth law student, deceased and Grace Forsythe deceased. When faced with the report containing these allegations de Wytt left St Andrews and resigned. He moved first to Edinburgh and then subsequently obtained various diplomas in public health and ultimately ran a successful nursing home in London, where he died in 1933.

–RH