52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations, Week 44: the Family Album

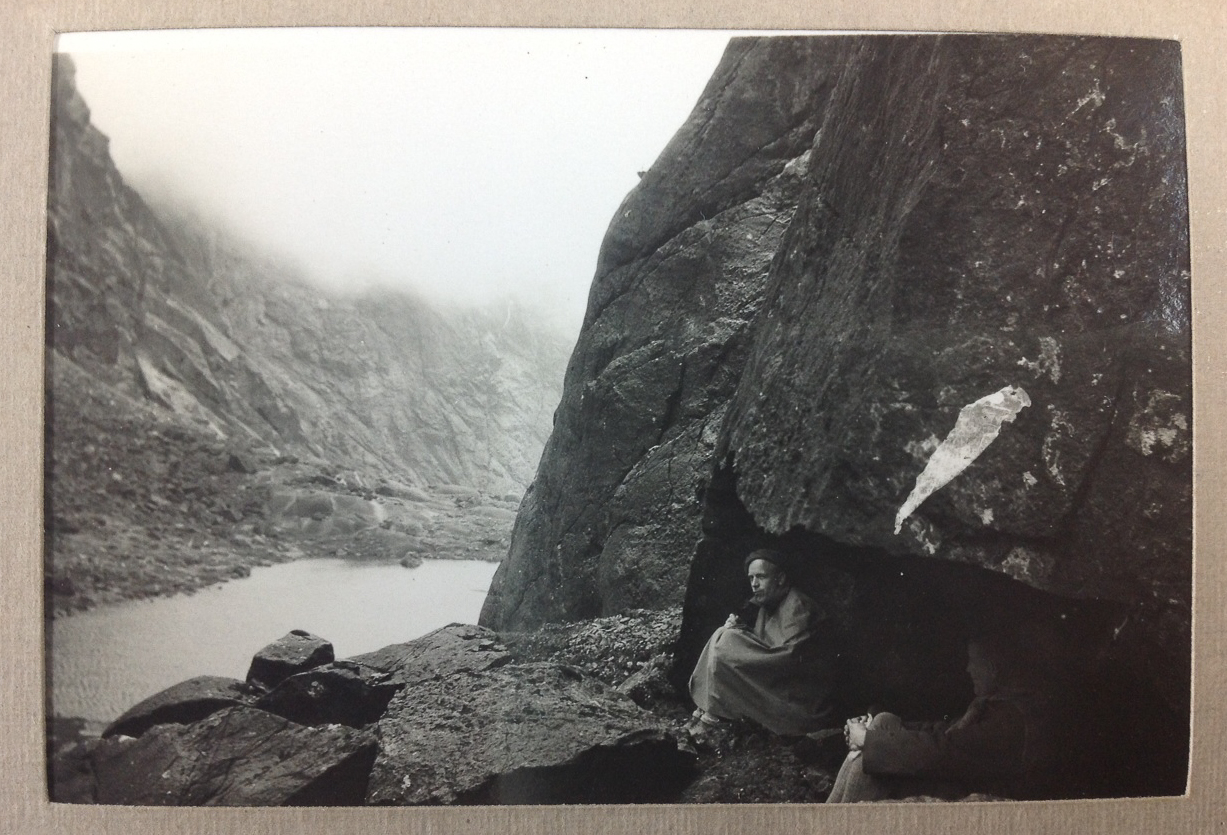

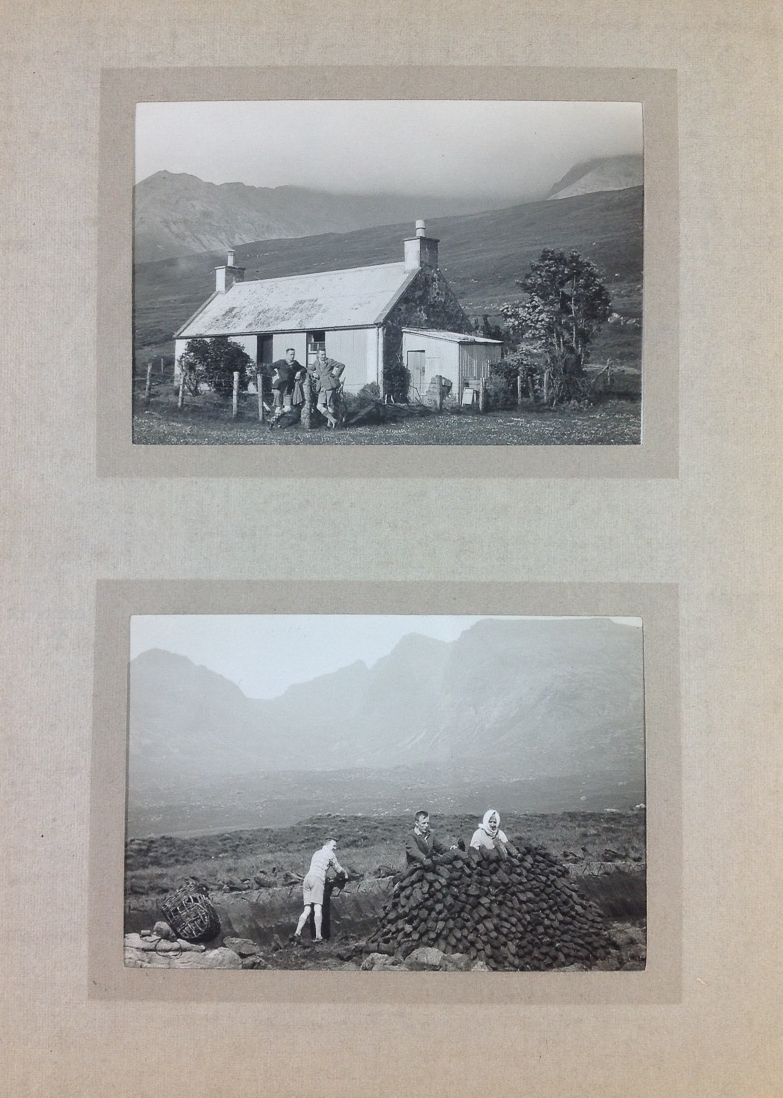

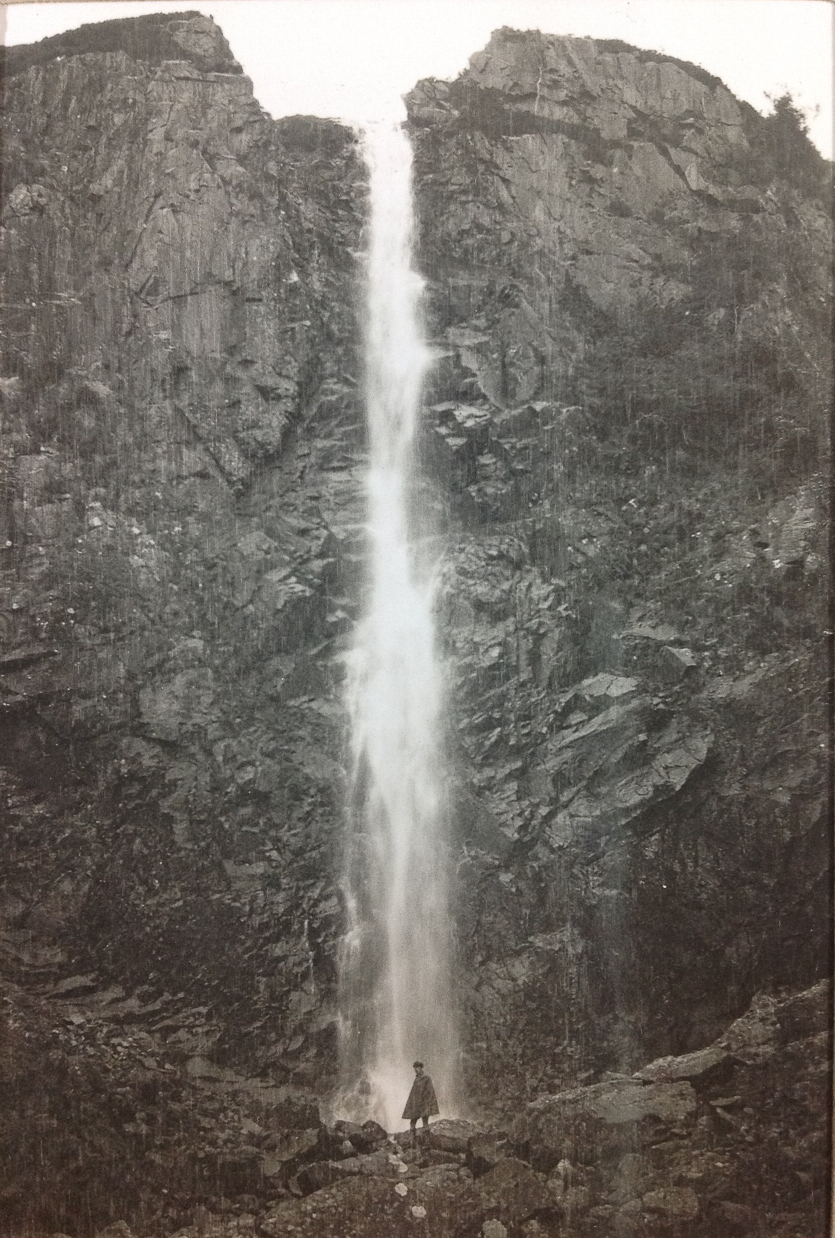

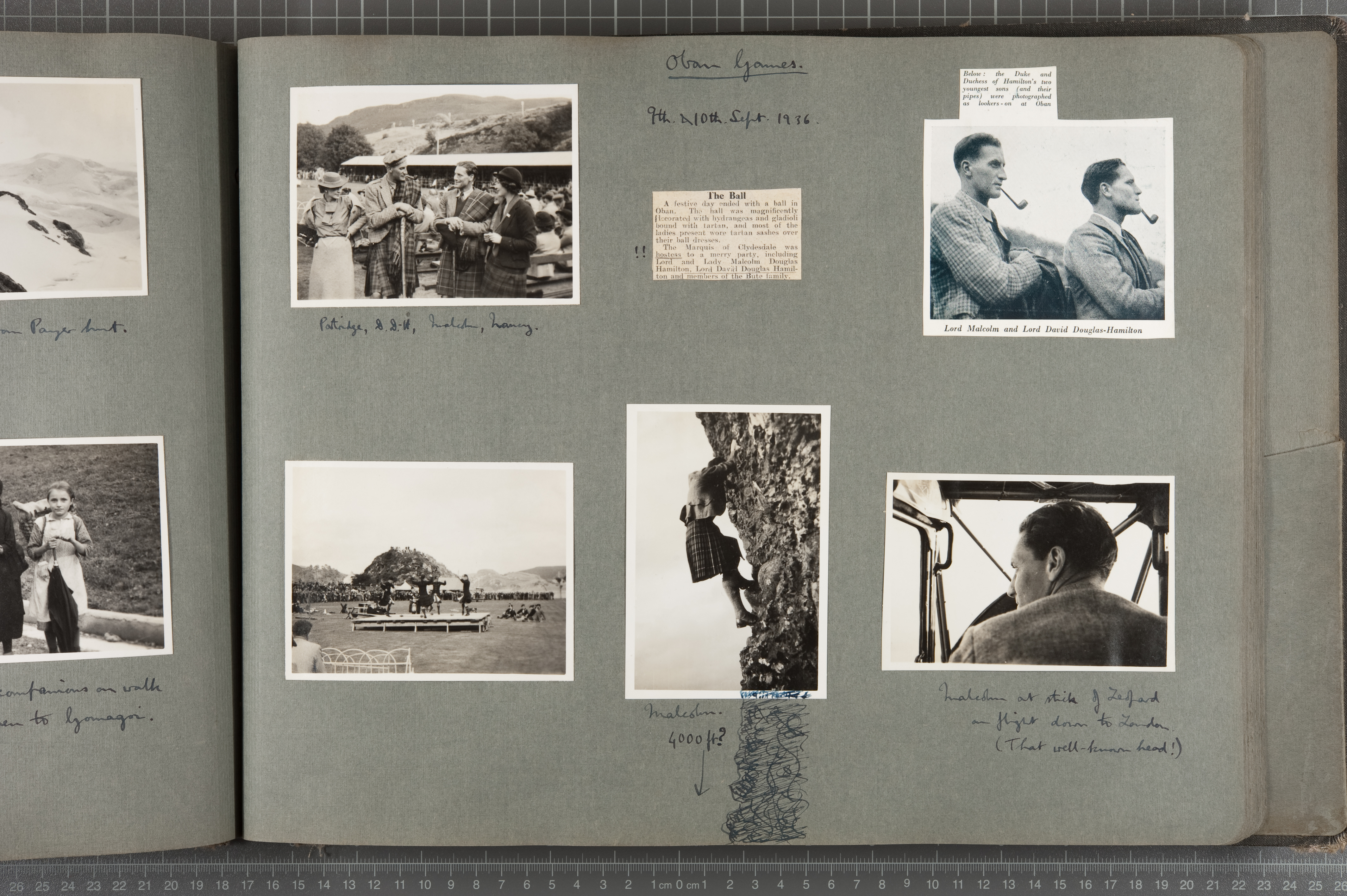

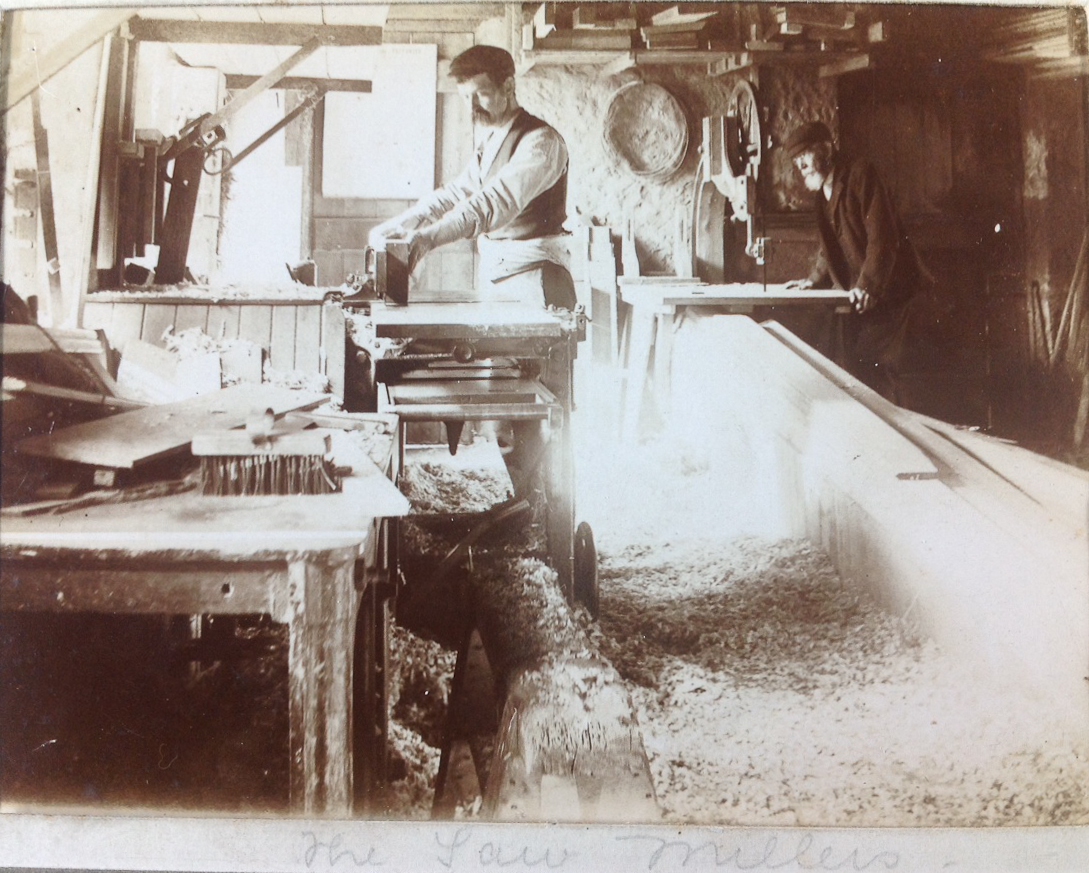

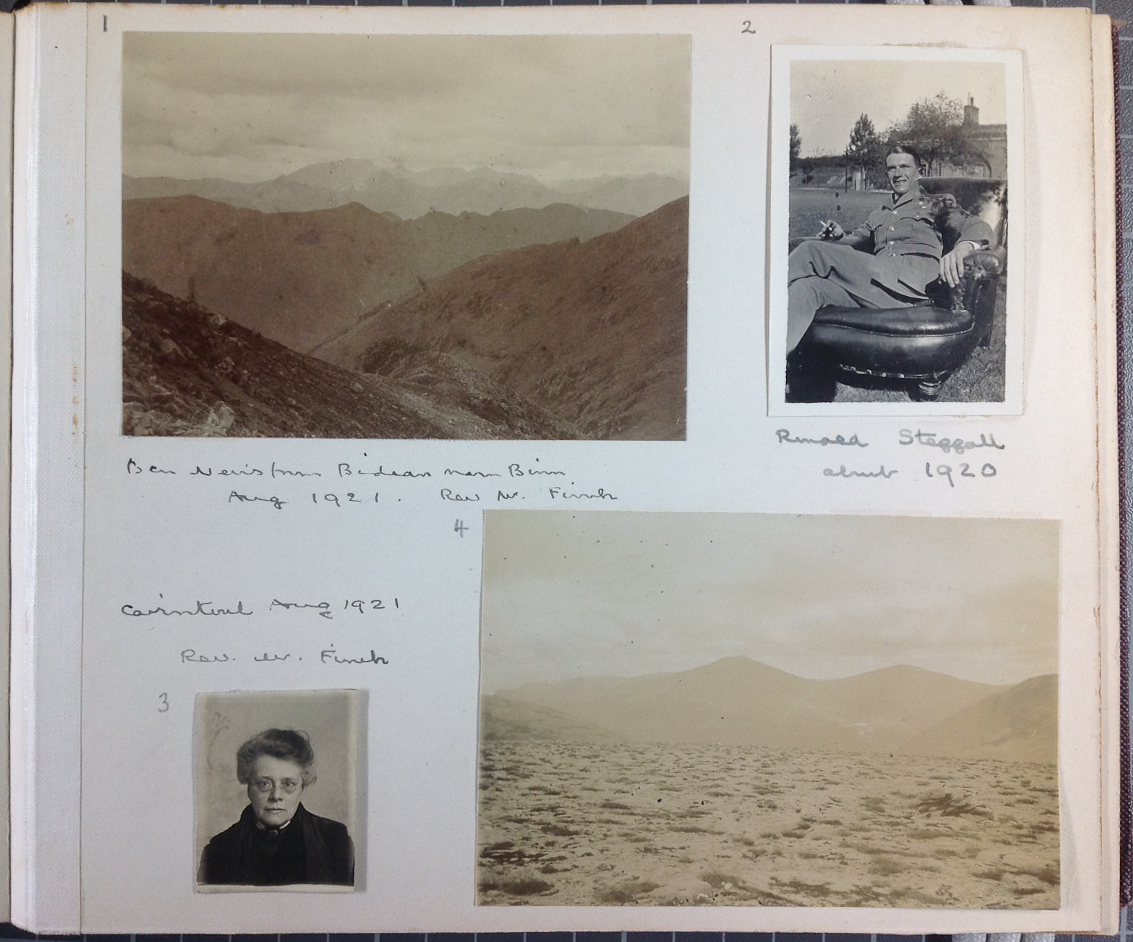

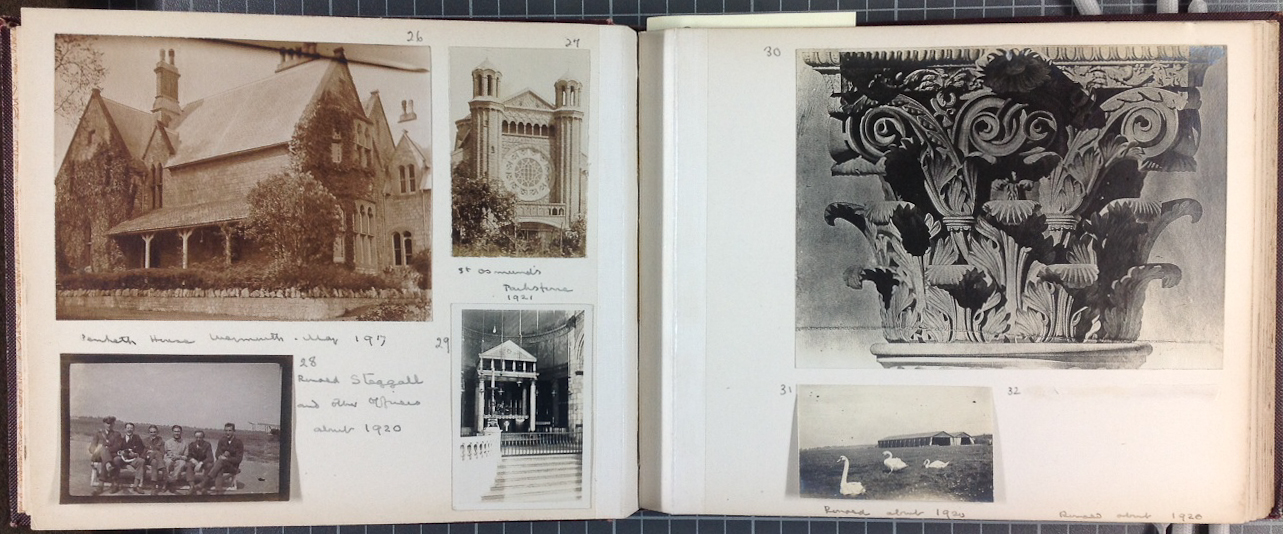

This Inspiring Illustration post on photography is inspired by a wonderful acquisition added to our Photographic Collection this week of a Scottish family’s photographs from the 1920s. Deviating, from talking about a specific photographic process, this post is focused on a particular presentation format, the photo album.

Although a certain degree of personal photography took place in the mid to later 19th century, it wasn’t until the advent of the hand held Kodak camera in 1888 that photography was truly adopted by a wider public. With this new technology, the need for tripods was minimised and extensive knowledge of chemistry was no longer a restricting factor. The film was sensitive and forgiving enough to allow hand holding these small box shaped cameras and the Kodak Company would process the film and return prints to its customers, taking all the guess work out the creative photographic process. ‘You press the button – we do the rest’ was their slogan after all!

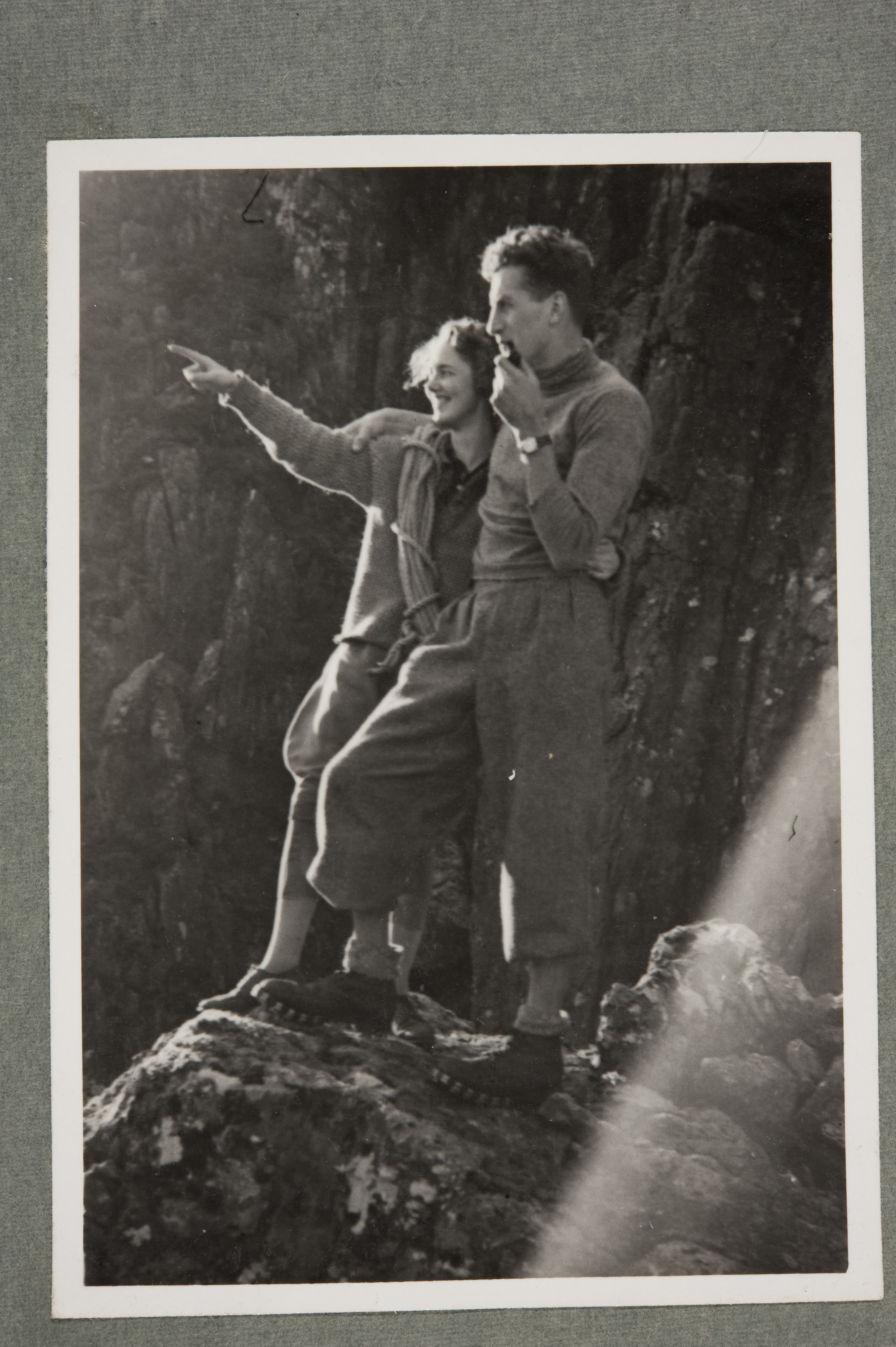

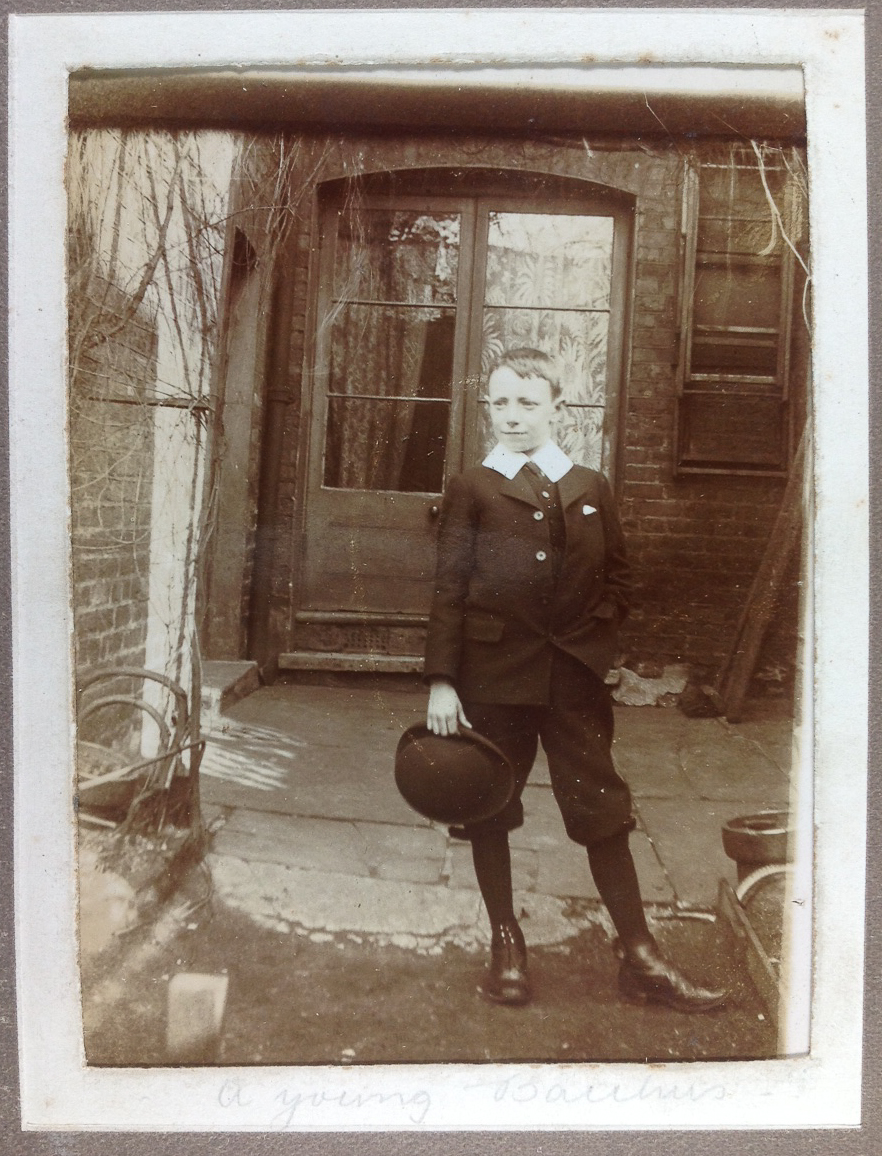

Aside from allowing the middle and upper classes access to a trendy pastime, this new technology empowered different groups, families and individual to engage in conceptualising and actively taking part in their own representation and documentation. In contrast to today’s pervasive engagement in social media, at the turn of the century the conventions of representing one’s self in a single image, let alone in a visual narrative such as an album, were concepts which had not been fully explored and were, to a degree, still open to interpretation.

When photographing one’s self or one’s family, how should one depict their story?

When photographing one’s self or one’s family, how should one depict their story? Is it necessary to engage in a chronological narrative of events in one’s life? In what person is such an album captioned? Who is the intended audience for the family album? Is an album created for one’s self, for their immediate family, ones descendants, a wider public and how should these distinctions affect the spirit and content of an album?

For the last decade, if not more, the subject of family photo albums, and more generically vernacular photography, has been the focus of much interest and study by visual anthropologist, photo theorists, and historians. This interest has also not escaped commercial exploitation in photography art galleries and the commercial photography market. As a trend it underlines one of the wonderful things about photography, which is its inherent flexibility and adaptability to interpretation and exploitation from different perspectives by specialists in diverse disciplines.

For instance, a casual family snap of someone’s aunt in her sun dress during a picnic on the beach, can be adapted to so many different purposes. Once could examine the clothing of the period, the details of the surroundings may be of interest, what the people in the photograph are doing may be very telling vis-à-vis cultural practice, the way in which individuals are choosing to represent themselves or the way in which the photographer is portraying someone and the varying degrees of collaboration and authorship between these two points can be very revealing.

As well, a great deal can be derived from the juxtaposition of images within an album and the narrative sequence they have been put into. There is so much about photographs which go beyond mere representation, that a photograph will always carry more value and information than its creator had originally intended.

Is sitting down with a family album with one’s children and grandchildren a thing of the past?

Due to its proliferation in the 20th century, vernacular photography and its presentation in family albums provides an endlessly rich resource for the interpretation and study of this period. Moving into the 21st century though, an era of mobile phone photography, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, cloud storage and the fugitive nature (easy to delete, alter or lose) of digital photographs, what testament to our documentation of our personal lives will stand the passage of time? Is sitting down with a family album with one’s children and grandchildren a thing of the past? Will albums, as family histories, heirlooms, and broader documents of our behaviour and cultural heritage be passed down from one generation to another? Will they be lost behind social media passwords, firewalls, failed hard drives and the fine print of copyright laws which drive our existing photo sharing processes?

The answers are unclear, but what is certain is that in this transition from traditional photography into the digital era, there will be a ‘dark age’ of visual representation spanning the period that it takes for our means of preserving images to catch up with the technology to create and share them.

–MB