52 Weeks of Inspiring Illustrations, Week 48: the Trajectory of the Photographic Medium

Over the past year staff from the Special Collections Division have been putting together posts highlighting ‘Inspiring Illustrations’ of material in our collections. Representing the Photographic Collection, I chose to conduct a survey of photographic media in order to underline the unique characteristics of individual photographic processes and plant the seed of interest for further investigation in our readers. Hopefully, demystifying photographic media has inspired the connoisseurship of the finer distinctions between the photographs which inhabit our archives, museums, albums, scrapbooks, shoeboxes, CDs, hard drives and cloud storage accounts.

This, my last post of this series, is a timely one as just two Fridays ago the UK government has proposed the closure of the country’s National Media Museum in Bradford which houses some the nation’s and the world’s most prized photographic heritage. If one asked a cross-section of the public to underline what are the most important artistic and visual media from our history, many would fall back on the standards taught in elementary or secondary school and make reference to the great painters, sculptors and architects celebrated throughout antiquity, the middle ages, the renaissance, and the modern era up to the 1st World War. The reason for this predictable response is that these media fit very comfortably within the long established canons of art historical practice, theory, and their parallel museum interpretation. It is a relatively small minority in the public who would automatically identify photography as being of particular significance to our collective history. As it is comparatively a very young medium (174 years old), this limited recognition is to be expected as the education system has only engaged directly with photography for a few decades , and is still striving to catch up with the inclusion of this medium into its pedagogical framework and curriculum. However, beyond academic curricula and museum mandates there is a change in cultural perception that must take place if the preservation of photographic heritage is to be secured.

As an inherently reproducible medium, when a photograph is placed on a museum wall, it challenges the museum and art gallery ethos based on the fetish culture of the rare and unique which permeates the traditional interpretation of the museum’s role. To single out a photograph from its technological context and role as a tool for dissemination and reproduction attempts to fit photography within a framework for interpretation which does not address the meaning implicit in its function as a tool of mass communication. In reaction to this dilemma, curators espousing contemporary values, photographic books, periodicals, gorilla art installations, and the internet have all gone a long way towards underlining photography’s more complex interpretation as being partisan to media, industry, consumerism, and as a personal and family driven cultural practice. In short, the diverse sites, formats and cultural mechanisms of photography’s dissemination are crucial to its interpretation.

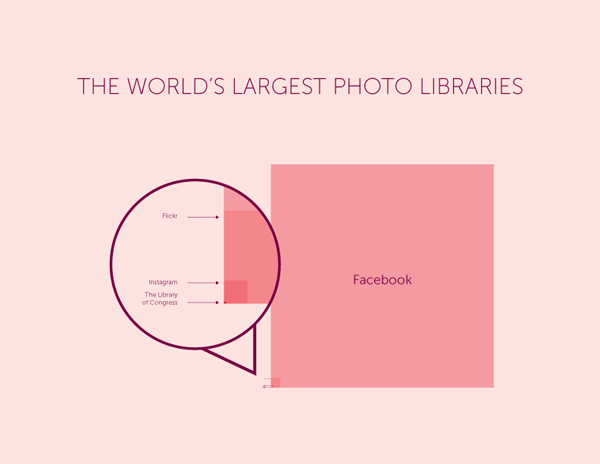

Proportionally speaking, photography is foremost a commercial medium, and one which for generations has been an omnipresent form of visual communication. However, like other utilitarian practices such as architecture or traditional crafts, photography is ever increasing as means of personal expression and interpretation of our daily lives. Quoting 1000memories from a blog post in 2011 by Michael Zhang about the relative sizes of the world’s largest photo libraries, “Already Facebook’s photo collection has a staggering 140 billion photos, that’s over 10,000 times larger than the Library of Congress.” In comparing recognised historic collections with the likes of Facebook and Instagram, one can plainly see the exponential growth in society’s creation and application of photography in its daily visual vocabulary. In 2012 Facebook on average had 250 million photos uploaded per day. Instagram’s website claims that they have:

Proportionally speaking, photography is foremost a commercial medium, and one which for generations has been an omnipresent form of visual communication. However, like other utilitarian practices such as architecture or traditional crafts, photography is ever increasing as means of personal expression and interpretation of our daily lives. Quoting 1000memories from a blog post in 2011 by Michael Zhang about the relative sizes of the world’s largest photo libraries, “Already Facebook’s photo collection has a staggering 140 billion photos, that’s over 10,000 times larger than the Library of Congress.” In comparing recognised historic collections with the likes of Facebook and Instagram, one can plainly see the exponential growth in society’s creation and application of photography in its daily visual vocabulary. In 2012 Facebook on average had 250 million photos uploaded per day. Instagram’s website claims that they have:

100 million Monthly Active Users

40 million Photos Per Day

8500 Likes Per Second

1000 Comments Per Second

Looked at statistically, the volume and omnipresence of modern photography is staggering! When thinking about museum and heritage collections, other than photography, it is rare that any media can claim to have its admirers so consistently fulfil both the roles of appreciation and creation. The current level of engagement in both the consumption and creation of photography is unprecedented and adds a dimension to how entrenched the medium is in our collective cultural experience.

So why is it that photography is given short shrift in the context of cultural heritage? Rather than its direct engagement in our lives underlining its importance, have we been desensitised to our investment in the medium and the manner in which it shapes our communication? Quoting Rachel Nordstrom, a member of the Photo Team here at St Andrews, it seems that we’ve forgotten that “only 175 years ago photography was magic!” As a meeting point of science and art, photography was a transformative medium which changed the way the world related to itself. Now perceived as a commonplace medium, our role as managers of photographic collections is to rekindle the spark of wonder that surrounds photography and ensure that its technological history as well the development its cultural practice are not lost.

!['Napoli Museo, Sala dei Marmi [Naples Museum, Salon of Marble]' by G. Sommer, 1880 (St Andrews ms-29951-10.35)](https://special-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2013/06/ms-29951-10.jpg)

–MB

Reblogged this on Simon Hamer and commented: Black and white photography old style ... and great

Lovely old images.