52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 4: The Complete Servant

Many items which appear in our blogs are visually stunning. The focus of this blog, The Complete Servant, by Samuel and Sarah Adams, is certainly not this. Acquired by the Library between 1826 and 1864, it has a non-descript paper cover (the original wrappers in which it was issued), and its pages are uncut and somewhat grubby along the fore-edges. But its contents are stunning, offering a wealth of information as to the roles of servants in the first half of the nineteenth century. As the old saying goes, never judge a book by its cover…

Published in 1825, as the preface claims this was the first book to attempt to define the relations between masters and servants, as far as household duties were required:

we have had no work, which, like the present, addresses itself to the actual personal practice of their duties; which defines them as they actually belong to the various classes; and instructs servants in the way and mode of performing them with skill, advantage, and success.

The Complete Servant, p. iii.

In addition to being of use to servants “who desire to perform their duty with ability, and to rise in their career to higher and more profitable situations” the work was deemed to be of great benefit to masters and mistresses, for it would advise them of their own duties, as well as “enabling them to estimate the merits of valuable servants”.

The authors were well placed to write such a work, both having worked their way up through the ranks of servants, Samuel from footboy (a boy, in livery, employed in the place of or to assist a footman), groom, footman, valet, and butler, before finally becoming a house-steward, and Sarah from maid of all work, house-maid, laundry-maid (responsible for washing “all the household and other linen belonging to her employers”), under-cook (supervised by the cook she managed the roasting, boiling, and dressing of all plain joints and dishes, as well as the fish and vegetables), housekeeper, and lady’s maid, to her final post of “housekeeper in a very large establishment”. Indeed, in the process of writing this work Sarah was able to draw upon the advice and assistance of her employer, “A lady of high rank”, for help with some of the articles.

The Complete Servant begins with a dedication, in which is considered the expenditure of a household (what percentage of your annual income should go on household expenses, servants and equipage, clothes and extras, rent and repairs, and what should be reserved); the number and description of servants to be employed, according to income; and the management of the household by the mistress of the house. Following this is a chapter on “advice to servants in general”, wherein they are not only advised on how to behave in a household, but are also given money advice through the medium of The Savings Bank. Then begins the text proper, where Samuel and Sarah Adams take us through the various servant roles.

There are too many to list them all here, but they include all ranks, from the lowly Stable Boy and Servant of All Work, to Housekeeper, Lady’s Maid, Butler, and House Steward (a post “seldom adopted except in families of noblemen or gentlemen of great fortunes”). Also included in the list are non-permanent positions, such as the Chamber Nurse – she formed “no part of the establishment of healthy families” but was “in every family…a necessary auxiliary for longer or shorter periods”. The work closes with an appendix which includes such useful information as Marketing Tables, Laws respecting master and servants in general, Fares to the Opera House (from various London addresses), and a “List of French and other Foreign Words and Phrases in common Use, with their Pronunciation and Explanation”.

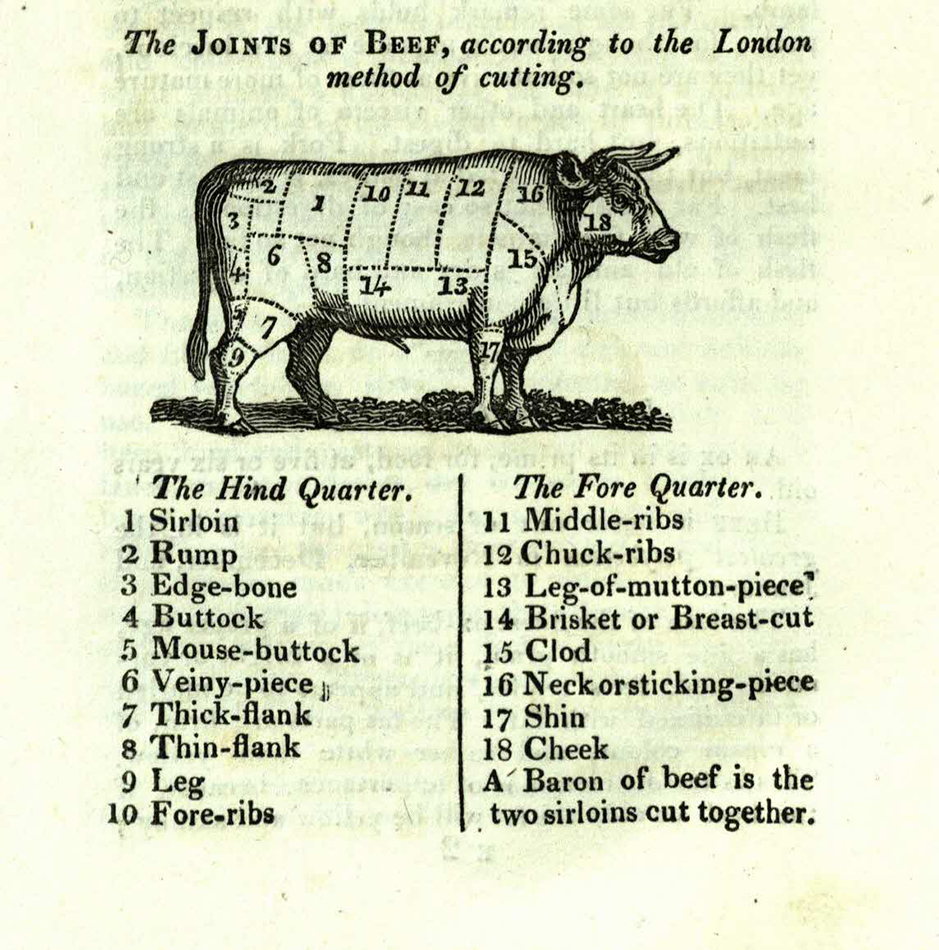

It is not only instruction which is given; The Complete Servant is littered throughout with useful receipts (recipes). For example, under the Housekeeper section are to be found many receipts for food and drink (such as Banbury cakes, crumpets, quince marmalade, apricot wine, walnut mead wine), as well as receipts for perfumery and distilled waters. Although the Housekeeper was responsible for selecting the meat for the family (there are very nice illustrations of the joints of beef, veal, mutton, and pork), it was the Cook who was in charge of its preparation – here are found instructions on boiling, baking, frying, and salting. Under the role of the Head Nurse are found listed the diseases of children, together with remedies, whilst family medicines are the responsibility of the Chamber Nurse. Instructions on how to revive faded black cloth, or to clean gold lace and embroidery were duties for the Valet, whilst the Groom is informed on how to treat sores and bruises in horses, indicating his need of basic knowledge of veterinary medicine. This comprehensive and influential manual inspired many imitations, and culminated, a generation later, in Mrs Beeton’s famed Household Management.

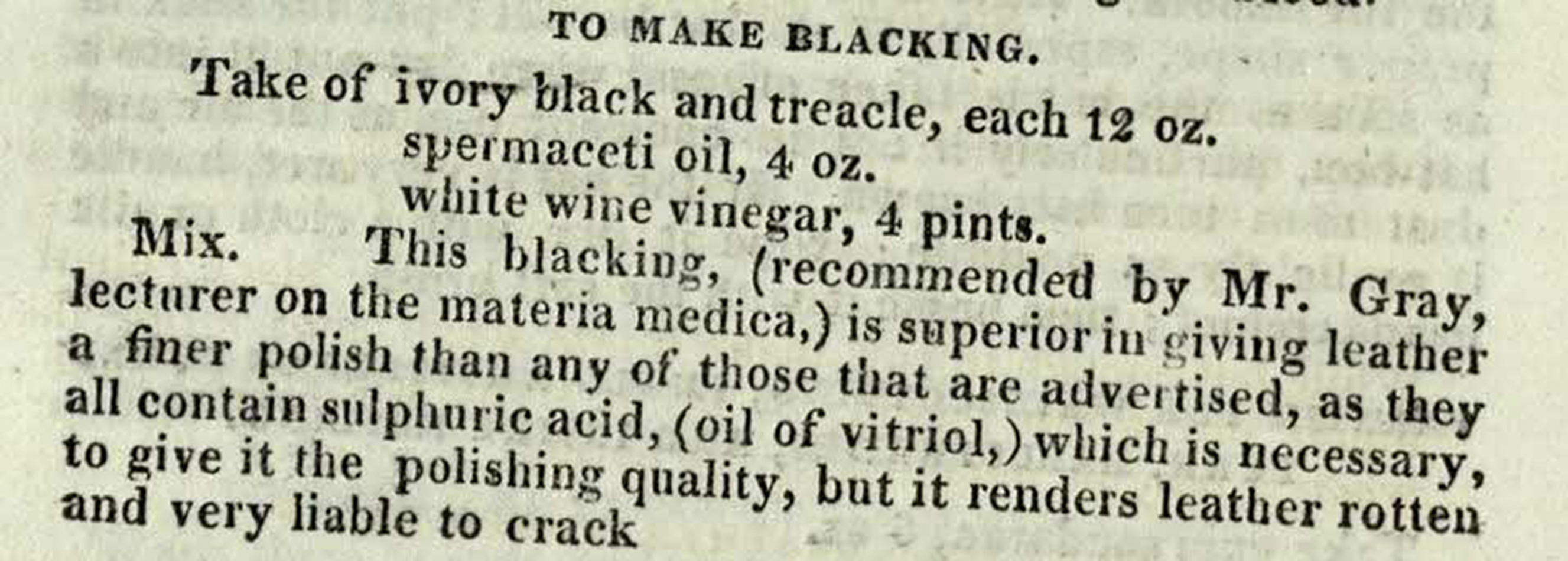

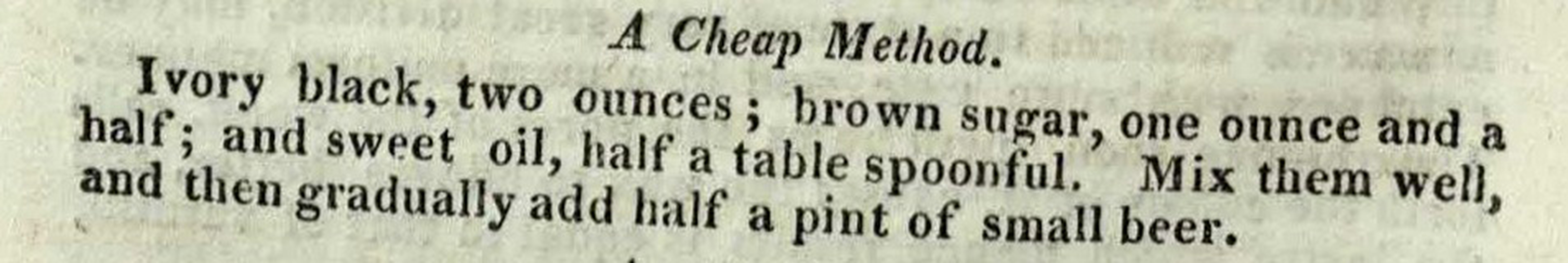

Given that The Complete Servant was intended for practical use, I had to have a go at reproducing one of the receipts. Tempting though it was to go for a food recipe, I decided to try something different, and chose something from the role of the Footman: blacking (a shoe polish). The Complete Servant contains seven receipts for blacking, two of which I tried – the main recipe containing oil and vinegar, and “A Cheap Method”.

Take of ivory black and treacle, each 12 oz.

Spermaceti oil, 4 oz.

White wine vinegar, 4 pints.

Mix.

The Complete Servant, p. 390

Ivory black, two ounces ; brown sugar, one ounce and a half ; and sweet oil, half a table spoonful. Mix them well, and then gradually add half a pint of small beer.

The Complete Servant, p. 390

I have to admit that I chose ones which offered ease of getting ingredients, but even so some substitutes had to be made. The main ingredient of both is ivory-black – a granular material produced by charring animal bones. This wasn’t going to be easy to get hold of, so I substituted charcoal (kindly supplied by Norman Reid), which I ground with a pestle and mortar. The spermaceti oil of the first recipe was substituted with jojoba oil, and for the small beer (a beer which contains very little alcohol) I simply used a low-alcohol beer – although upon reflection, I wonder if using half this and half water would have been a better substitute (I certainly had a sticky, beer-smelling shoe at the end! Luckily this wasn’t a problem, as the shoes were destined for the scrap-heap – thanks to Jane Campbell for supplying them). Sweet oil, used in the cheap recipe, is another name for olive oil.

Both recipes were simple to make – the first required the ingredients simply to be mixed together, the second to mix everything except the small beer, which was to be added gradually at the end. What immediately struck me was how liquid both blackings were – I was expecting something like a thick paste, especially from the one containing treacle. Perhaps ivory black reacts differently to charcoal, or perhaps I used the wrong measurements – I went for weight, but fluid ounces may have been intended. The ground charcoal also made the blacking very grainy, which would surely threaten to scratch shoes (although it did brush off).

Sadly these recipes don’t give instructions on how the blacking is to be applied. Does one dry it immediately, or leave it to dry naturally before buffing with a cloth? Further information was not forthcoming in the instructions for the footman, but another text, Thomas Cosnett’s The Footman’s Directory and Butler’s Remembrancer, published in 1823, does give information: the shoes “must be quite dry before you black them, or else they will not shine. Do not put on too much blacking at a time, for, if it dries into the leather before you can use the shining brush, the leather will look brown instead of black”. Additionally, the blacking should always be stirred up well before use. I was all set to go.

The result with the cheap recipe was very dull. When comparing the shoe to the untreated one, a clear difference was seen. Perhaps this cheap version was not intended to give a high shine, or more vigorous shining was needed on my part. I would have to follow Cosnett’s advice: “If your boots and shoes do not look bright after one blacking and rubbing, do them again until you are satisfied with them”. A rigorous go with a polishing brush did produce a better shine. The recipe with oil and vinegar, however, did produce more of a shine when first applied. Indeed, it is stated that this recipe “is superior in giving leather a finer polish than any of those that are advertised” – although I found that after buffing with a polishing brush the cheap method seemed to give the better shine. For a truly polishing quality it appears that sulphuric acid (oil of vitriol) is needed, “but it renders leather rotten and very liable to crack”. But the recipe with oil and vinegar was popular, for it is also found in Colin Mackenzie’s, Five Thousand Receipts in all the useful and domestic arts, published in 1823.

Whether or not my blacking was anything like the original, I don’t know, but they certainly did dye things a darker colour – after many applications. Yet in future I think I’ll stick to modern shoe polish….

Briony Aitchison

Lead Cataloguer – Lighting the Past

[…] The Complete Servant: A guide from 1825. […]

[…] forest * on the bench | Deb’s Studio Blog * back in business (almost) | The Caseroom Press * 52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 4: The Complete Servant | Echoes from the Vault * Partilha | A menina cos(z)e? * We Desperately Need Your Help! | Belle […]