52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 7: A Complete System of Cookery

When word went around that this year’s Special Collections’ Christmas party (blog forthcoming) was to be hosted by Maia Sheridan, with everyone chipping in by bringing food made to historical recipes, I immediately scoured the shelves for something suitable. My eye fell upon a rather plain looking volume, which, when opened, revealed page upon page of detailed menus.

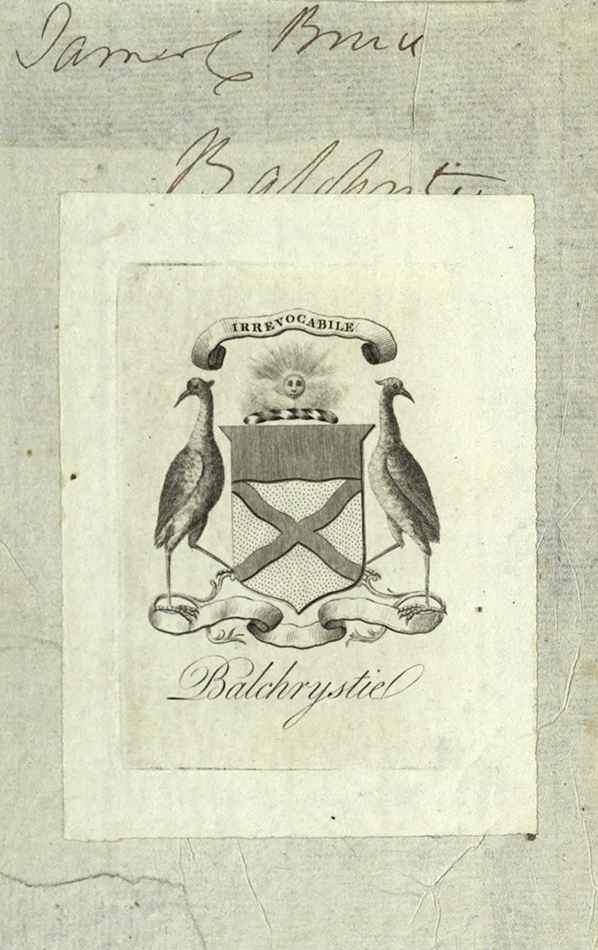

This humble-looking book is John Simpson’s A Complete System of Cookery. On the front pastedown is the inscription “James C. Bruce Balchrystie”, which is partially obscured by an armorial bookplate of ‘Balchrystie’ (motto ‘Irrevocabile’). Balchrystie is a Georgian house situated in the East Neuk of Fife, purchased by the Bruce family at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The book was donated to the library in 1934 “in memory of John Rollo, Esq., of Rodney Lodge, Perth and Edgecliffe, St Andrews” by his sister, Miss Rollo. It seems likely that the James Bruce of the inscription was Mrs Elizabeth Carstairs Bruce’s husband James; Mrs Carstairs Bruce was John Rollo’s aunt.

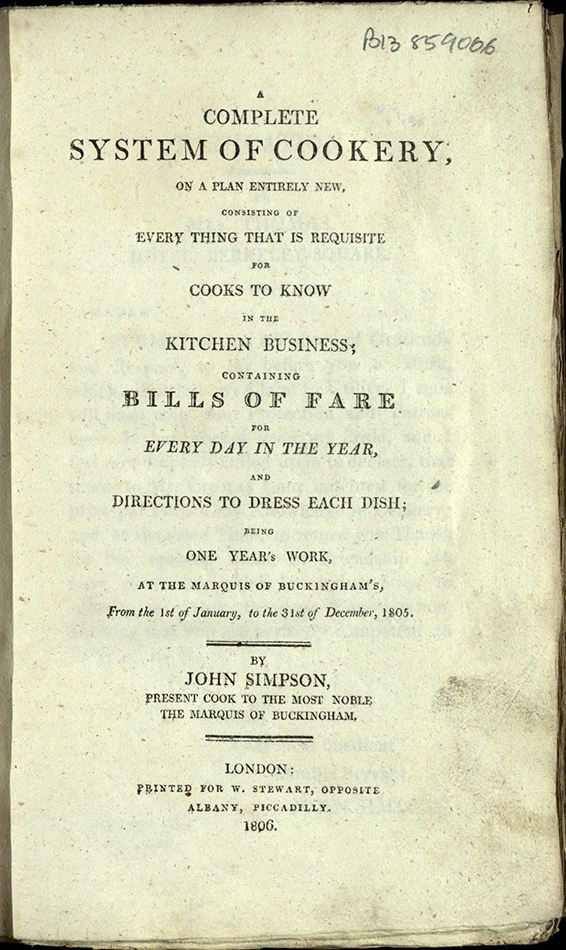

John Simpson was, at the time of publication in 1806, cook to the Marquis of Buckingham. Although he worked in an aristocratic household, his book was intended to be of use to a wide range of cooks:

The following work will be found very useful to cooks, clerks of the kitchen, house stewards (not being brought up to the cooking business) women cooks, housekeepers, and likewise to gentlemen and ladies who do not keep men cooks, and particularly to tavern-keepers.

A Complete System of Cookery, p. vii.

Although works dealing with the kitchen were already published, Simpson claimed that his work was on a new plan. Not only was the bill of fare (menu) set out for each day of the year, from 1st January to 31st December 1805, but he also only included dishes which he himself had put into practice. He was quite scathing of those authors who listed a great number of dishes: “I may safely say, that one half of them are useless, as they are not put in practice by any one.” Additionally, confectionary is not included in his Complete System of Cookery, for he has left out all “except what is actually requisite for cooks to know. They may pretend to be confectioners, but if they study their own profession, they will not have much time to attend to this department.” This very much reflects the distinction between a chef and pastry chef today.

After noting for whom his work is intended, the introduction then turns to the matter of meat. Simpson is keen that the butcher should deliver it no later than 6am, “for when the sun gets warm, the flies do much mischief”, and he gives instructions for the best ways to prevent the meat spoiling (by salting and by removing various pipes and kernels (glands, or rounded fatty masses) found in the cuts of meat), and how long each cut should be kept. Simpson also advocates fasting animals before slaughter – “twenty-four hours in winter, and forty-eight in summer”. The cook was to pay much attention to the management of the larder, one rule being not overstock the larder in summer: “one days meat beforehand is quite sufficient.”

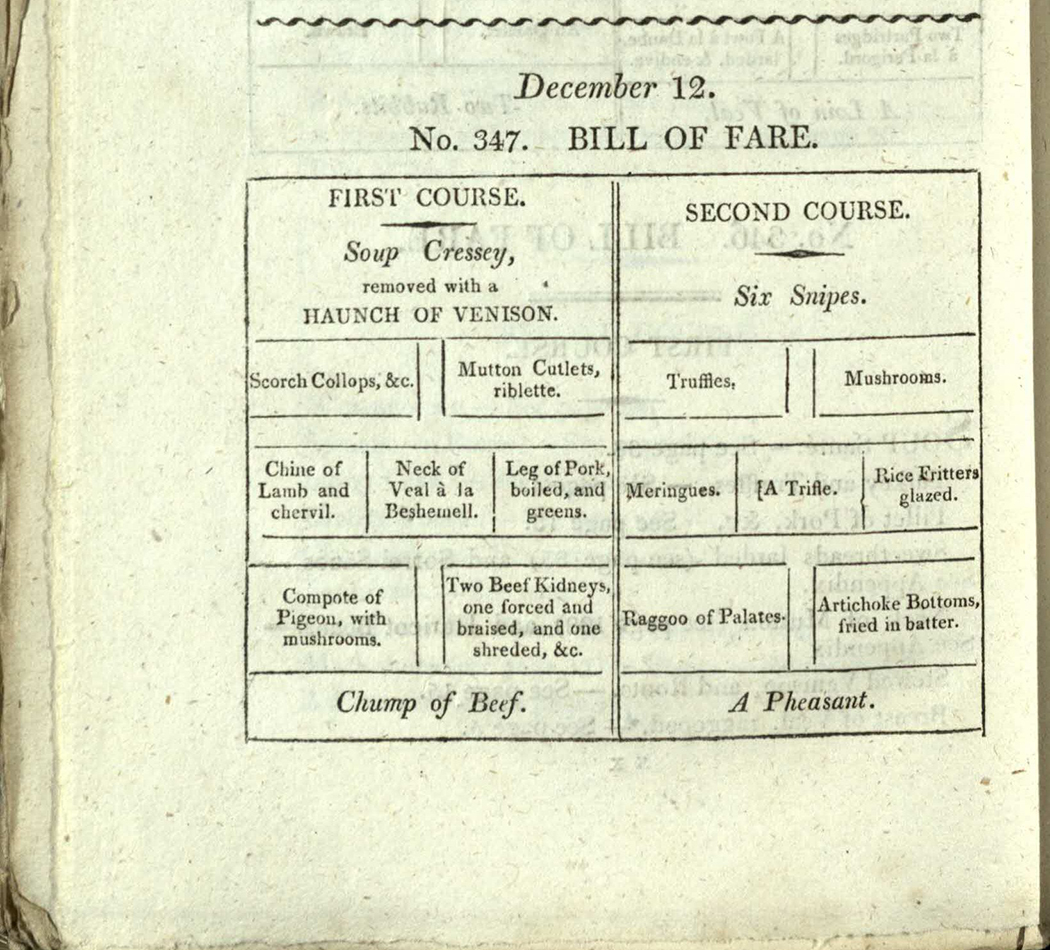

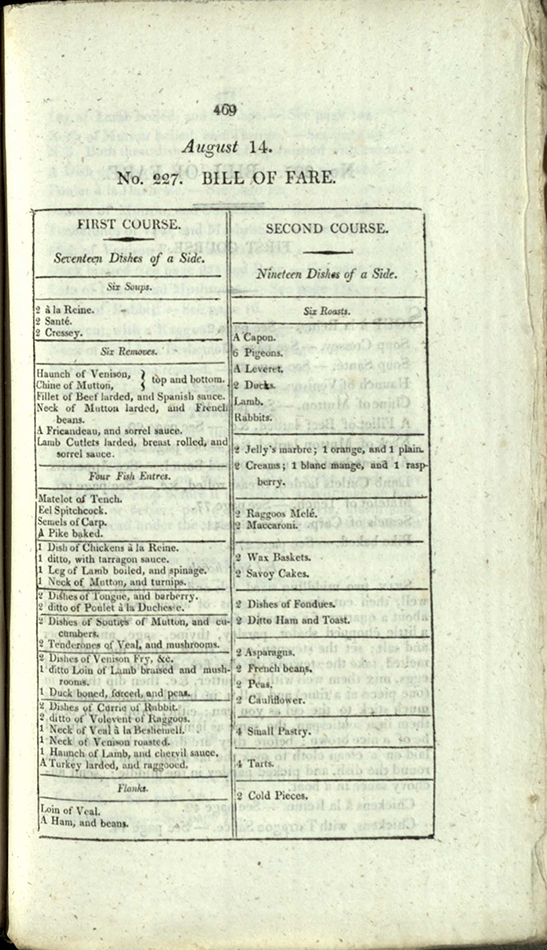

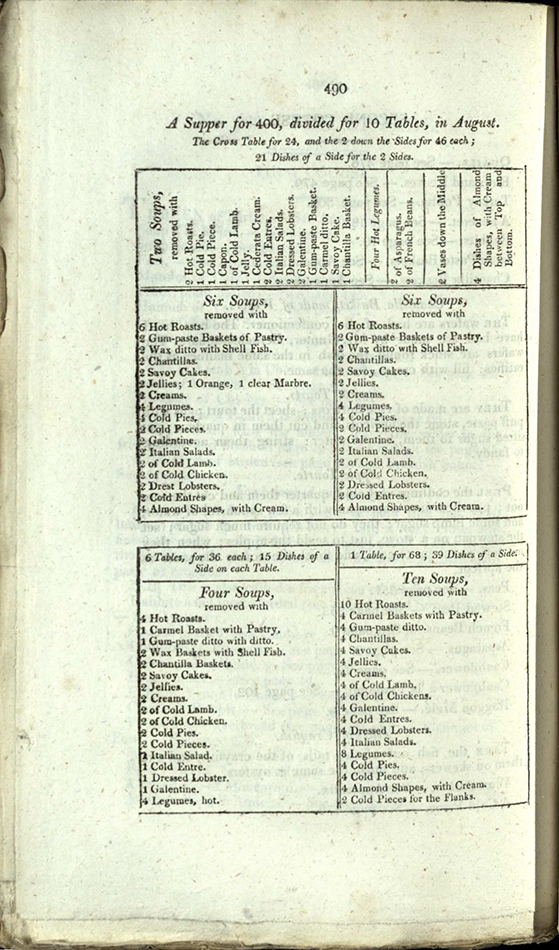

The bills of fare are set out diagrammatically into two courses, followed by the recipes for each item. Once a recipe has been given, it is not repeated, but rather the reader is referred back to the page on which it is found. The dishes are seasonal, but it is clear that some items are served throughout the year, such as macaroni, which appears, for instance, on January 1st, April 16th, and September 23rd. The number of courses can vary, clearly indicating the number at dinner on any given day. The bills of fare between 14th and 20th August are hugely augmented, suggesting that the Marquis was entertaining a large number of guests. Indeed, on p. 490 is a table showing “A supper for 400, divided for 10 Tables, in August.”

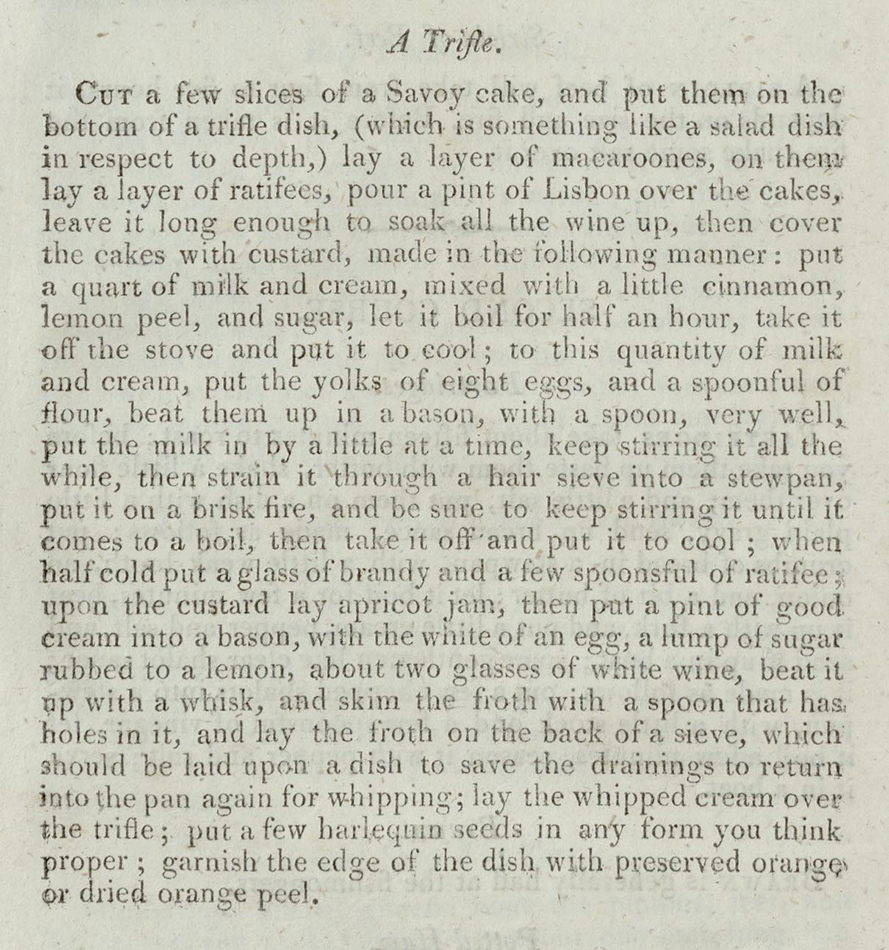

I was looking for something seasonal to make for our departmental Christmas party, and my eye fell upon the trifle. Although this was served throughout the year, it appears most frequently in December and January. With its layers of savoy cake, macaroons, and ratafia biscuits, not to mention Lisbon wine and brandy, I was hooked.

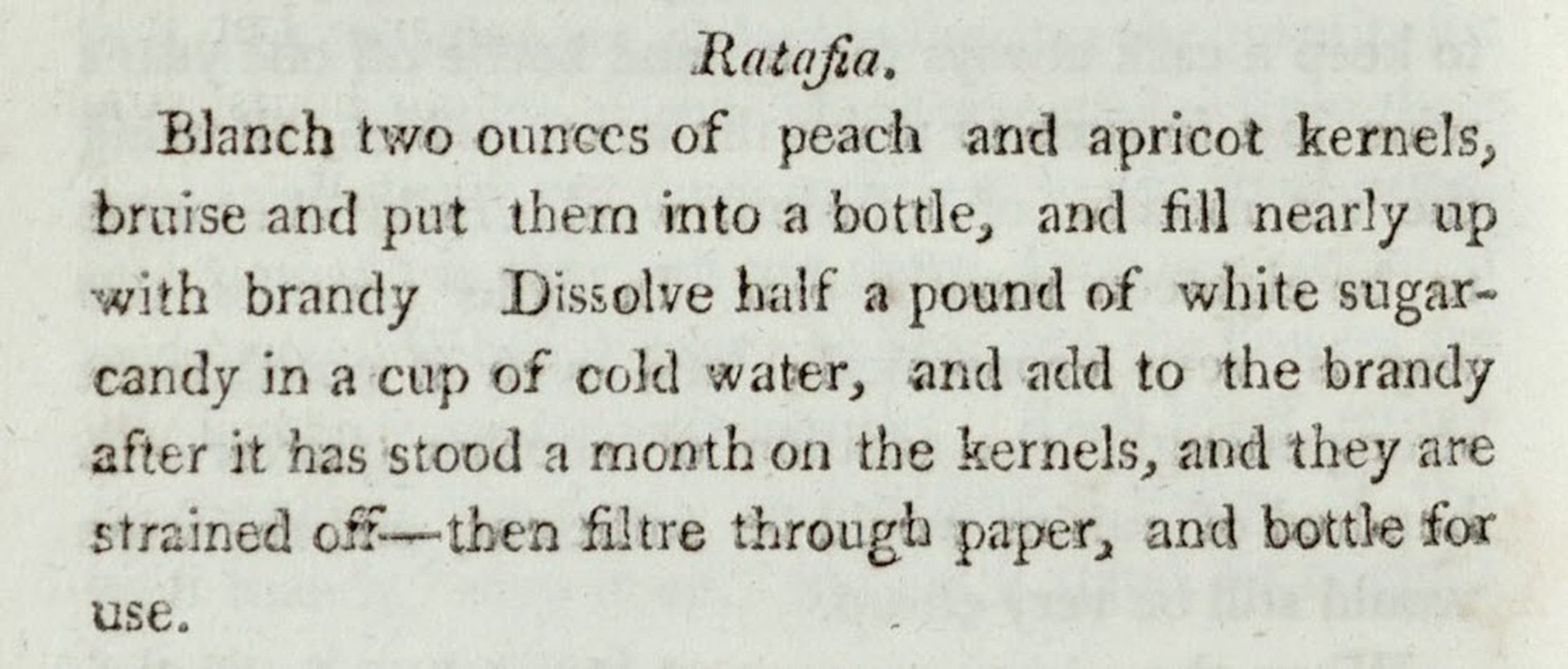

When making the trifle, I attempted to be as authentic as possible, but some substitutes had to be made. The recipe calls for Lisbon [wine], which, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “a white wine produced in the province of Estremadura in Portugal”. My colleague Ines Ricardo, suggested that today it may be a wine called Carcavelos, a liquorous wine produced in very small quantities by the Count of Oeiras, but this can be hard to find. It seems that a sweet wine was intended, so I opted for a Muscatel – kindly brought back from Portugal by Ines’ partner, Bruno Jacinto. Another liquid required by the recipe is “ratifee” (ratafia). Feeling adventurous, I decided to have a go at making my own, following a recipe found in the first edition of A New System of Domestic Cookery by Mrs Rundell, published in 1806.

Blanch two ounces of peach and apricot kernels, bruise and put into a bottle, and fill nearly up with brandy. Dissolve half a pound of white sugar-candy in a cup of cold water, and add to the brandy after it has stood one month on the kernels, and they are strained off–then filtre through paper, and bottle for use.

A New System of Cookery, p.246.

The recipe sounds simple, but it took some effort getting in to the kernels – having dented a rolling pin I finally resorted to a hammer. I have to admit that I was a little disappointed that mine doesn’t have more of an almond taste, but I suspect I may have added too much brandy to the quantity of kernels – for I had nowhere near 2oz. If I’d thought about it over the summer, I would have insisted that everyone in Special Collections eat apricots and peaches, giving the stones to me!

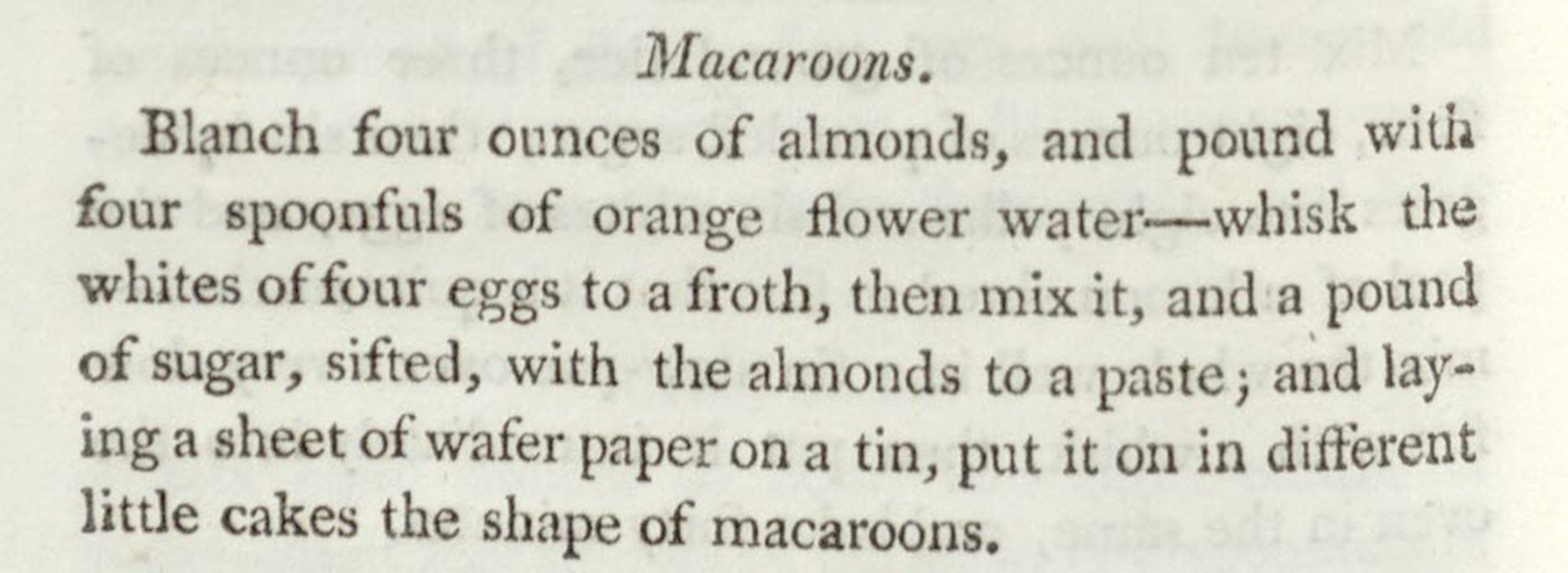

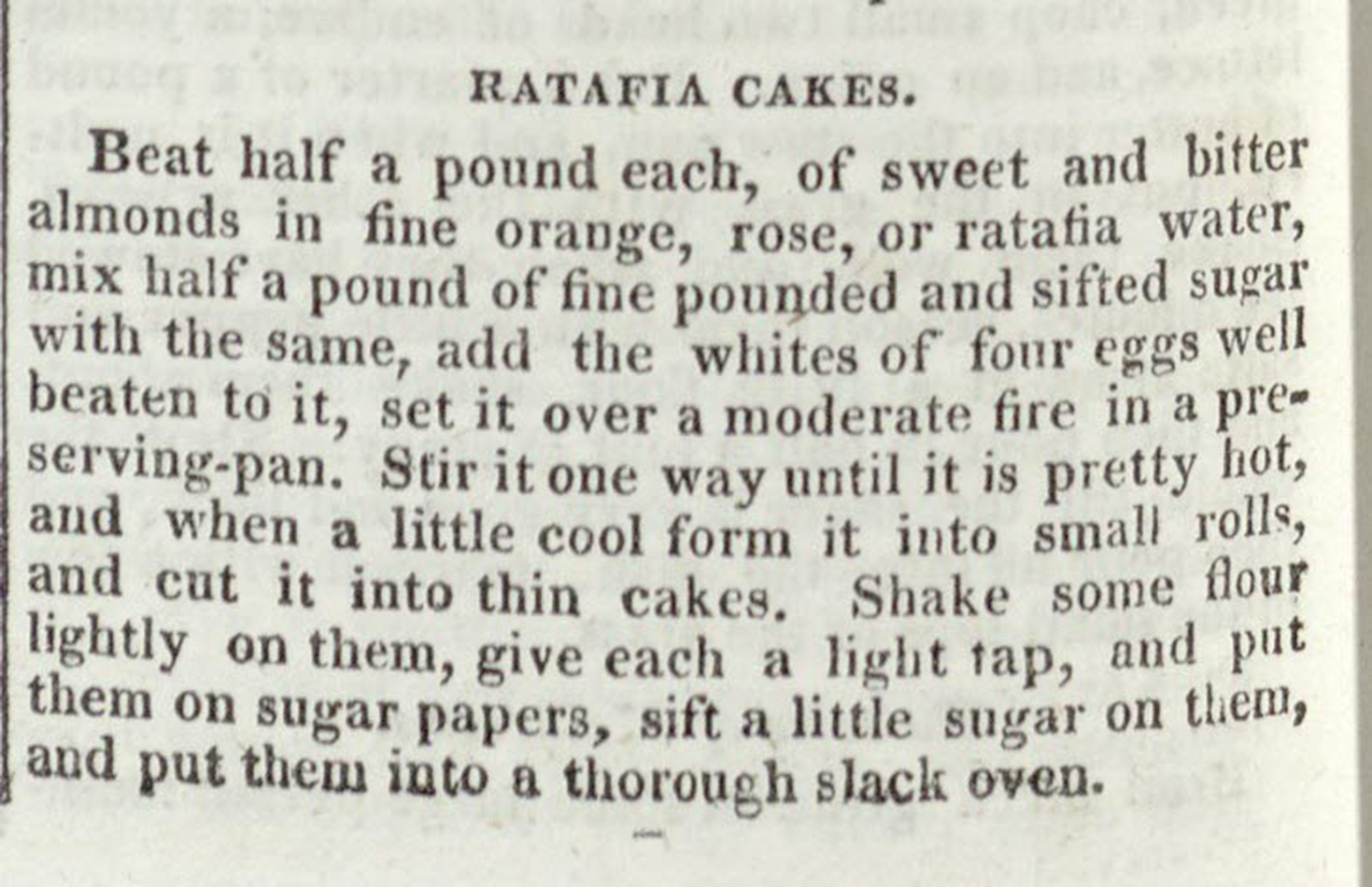

I was also keen to use the “macaroones” and “ratifees” in the layering, and so looked for contemporary recipes. No doubt Simpson would have been horrified at my making these, such things presumably being the work of a confectioner (and hence not to be found in his cook book). Mrs Rundell provided me with a recipe for macaroons, but I had to turn to Colin Mackenzie’s Five Thousand Receipts in all the Useful and Domestic Arts, published in 1823, for ratafia cakes.

Blanch four ounces of almonds, and pound with four spoonfuls of orange flower water–whisk whites of four eggs to a froth, then mix it, and a pound of sugar, sifted, with the almonds to a paste; and laying a sheet of wafer paper on a tin, put in on in different little cakes the shape of macaroons.

A New System of Domestic Cookery, p.224.

Beat half a pound each, of sweet and bitter almonds in fine orange, rose, or ratafia water, mix half a pound of fine powdered and sifted sugar with the same, add the whites of four eggs well beaten to it, set it over a moderate fire in a preserving-pan. Stir it one way until it is pretty hot, and when a little cool form in into small rolls, and cut into thin cakes. Shake some flour lightly on them, give each a light tap, and put them on sugar papers, sift a little sugar on them, and put them into a thorough slack oven.

Five Thousand Recipes in all the Useful and Domestic Arts, p.320.

Once everything was made, assembling could begin. The instructions in the recipe were easy to follow, but one had to read ahead. For instance, after boiling the quart (2 pints) of milk and cream together with a little cinnamon, lemon peel, and sugar, the recipe says “to this quantity of milk and cream, put the yolks of eight eggs, and a spoonful of flour”. At first glance this appears to suggest that the eggs and flour are to be added to the milk and cream, but it’s actually the other way around, for the recipe continues “beat them [the yolks and flour] up in a bason [sic], with a spoon, very well, put the milk in by a little at a time”.

To summarise, the trifle consisted of a layer of Savoy cake (recipe supplied by Simpson in the appendix – it was certainly hard work beating the egg yolks and sugar together for half an hour, but this was necessary in order to incorporate air to ensure a tender crumb), a layer of macaroons, and a layer of ratafia cakes. Over this was poured the muscatel, which was allowed to soak in before the custard was added. A layer of apricot jam followed (home-made – well, I had to do something with the left-over apricots after getting the kernels!), before being topped with the whipped cream (which included egg white, sugar rubbed to a lemon, and white wine). The final addition to the trifle (aside from the orange peel garnish) was to “put a few harlequin seeds in any form you think proper.” An initial search on Google for ‘harlequin seeds’ turned up results relating to marijuana – I felt sure this wasn’t what was intended! Indeed, harlequin seeds are minute coloured comfits or nonpareils, for which hundreds and thousands provided a suitable substitute.

And the verdict? Well, it seemed to go down well at the party, and the dish was scraped clean. It was certainly not what I was expecting from a trifle, for the flavours are very different to 21st century tastes – the perfumery of the orange blossom water in the macaroons, and the custard flavoured with cinnamon and lemon rather than the vanilla used today. So if you’re looking for something different when you’re entertaining over the festive period (or any other time of year for that matter), then you can’t go far wrong by consulting A Complete System of Cookery, which includes delights such as ginger soufflé, gooseberry tart, raspberry puffs, apricot tourte, and , of course, trifle.

Briony Aitchison

Lead Cataloguer – Lighting the Past

Reblogged this on Deanna-Cian Tarpey.

[…] today; sweet potato cakes, Swedish meatballs, roast turkey, fish pie, all from traditional recipes; Briony’s amazing trifle; gingerbread, almond simnel Christmas cake (1884) and 18th century lemon cheesecakes. All […]