52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 10: Artificial Fireworks from the Boy’s Own Book

Following our post on Christmas Decorations from the Girl’s Own Annual, this week’s Historical How-To comes from the Boy’s Own Book, found in the Copyright Deposit Collection.

Although our copy of the Boy’s Own Book is missing its title page, we know that this “popular encyclopedia of the sports and pastimes of youth” was first published in London in 1828 and in Boston in 1829. Based on the colophon and the pagination, which varied between editions, we believe that ours is a copy of the 9th edition, published in 1834.

According to sports historian Robert William Henderson in his book, Ball, bat, and bishop: the origin of ball games, the Boy’s Own Book “was a tremendous contrast to the juvenile books of the period, which emphasized piety, morals and instruction of mind and soul; it must have been received with whoops of delight by the youngsters of both countries.” While its tone may have lightened in comparison to some of its predecessors, the book is not entirely bereft of moral purpose, being intended as a healthy alternative to “publications of an objectionable character,” being “the cheap trash on which the hoarded shilling is usually expended” (Prelude, p. 5).

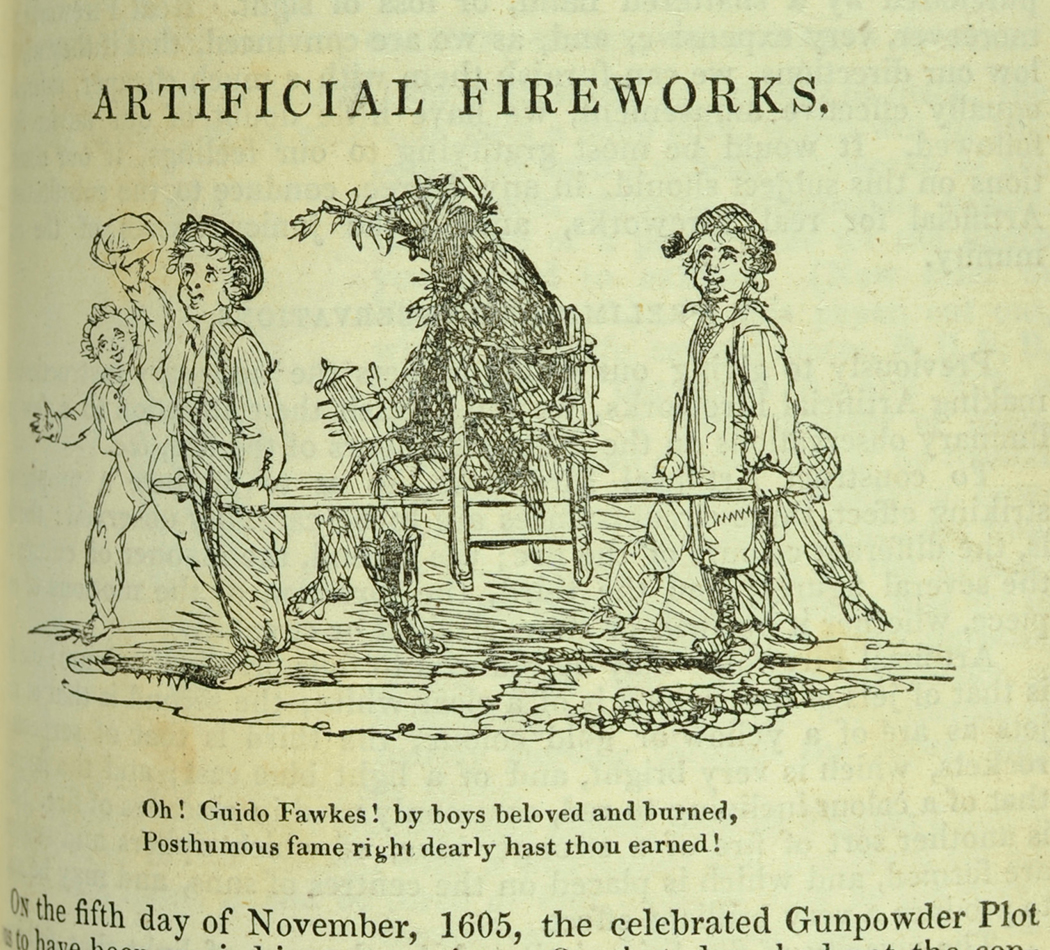

Often cited for its early description of the rules of baseball (under the name of “rounders”), the Boy’s Own Book also includes instructions for both indoor and outdoor games, information for the pigeon-, rabbit-, or silkworm-fancier, scientific recreations, and sleight-of-hand tricks. In a chapter enticingly called “the conjuror,” after a bit of historical preamble touching on the subject of the gunpowder plot, it gives instructions for creating artificial fireworks. While we’re a bit late for bonfire night, we offer up this little craft project in honour of Hogmanay.

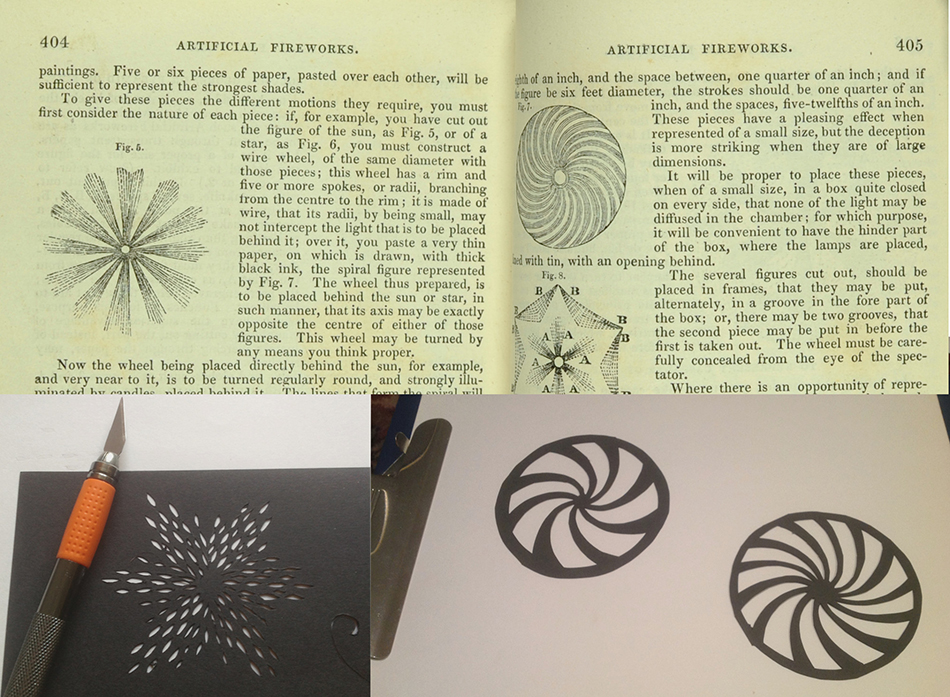

The basic principle behind the artificial fireworks is simple: the shape of the fireworks is cut out from “a paper that is blacked on both sides,” which is held in front of a candle or other light source. According to the text, “punches, fit for this purpose… may be purchased at the ironmongers’ shops,” (p. 403) but I’ve opted to use a craft knife and pre-blackened card from the stationery shop instead.

Once the shape has been cut out, “The vivacity of fire [is] imitated, by the rays of light that fall upon transparent paper… stained with different colours.” In contrast to the brightly coloured fireworks displays that we’re accustomed to today, the instructions describe fireworks as having just “four principal colours: the first is that of jets of fire, which is of a clear white; the second is that of such jets as are of a yellow or gold colour; the third is that of serpents or rockets, which is very bright, and of a light blue cast; and the fourth is that of a colour inclining to red, commonly used in cascades of fire.” (p. 402) Prior to the 1830s, pyrotechnicians could make sparks and fireworks in gold and silver, but could not produce strong colours. It was not until alchemists replaced the potassium nitrate in gunpowder with potassium chlorate that the combustion temperatures reached high enough to allow the use of chemicals to alter the colour of the explosions.

The Boy’s Own Book suggests tinting the paper by soaking it in water infused with saffron or prussian blue, and then, “after it is coloured, it may be made more transparent, by being dipped in, or rubbed over with, clear oil” (p. 401). Once again, I’ve used a bit of modern substitution, using tracing paper with a light application of watercolours.

Finally, to give the illusion of motion, a spiral design is drawn with thick black ink on very thin paper, which is in turn pasted onto a wire frame, “that its radii, by being small, may not intercept the light that is to be placed behind it.” The spiral is placed behind the cut-out firework, and “may be turned by any means you think proper.” As the spiral is turned, it creates the illusion of sparks moving outward from the center of the fireworks. I’ve used a couple of small sewing pins to hold everything together. Using these principles, various figures can be combined in a kind of shoebox diorama.

The instructions go on to show how more complicated spirals can be used to create illusions of sparks that seem to radiate in multiple directions at once, or rolled onto a frame to create cascades and fountains of fire, but I think I will content myself with this simple holiday card, and a sincere wish that your new year is a happy one!

Christine Megowan

Rare Books Cataloguer