52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 19: Diderot’s Encyclopédie and the art of making paper

This week’s blog focuses upon one of the greatest works of the Enlightenment and 18th century – the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean d’Alembert. In scope nothing like it had been previously planned. Based upon the Cyclopaedia of Ephraim Chambers, this was the first encyclopaedia to include items from many contributors (Diderot and d’Alembert being amongst them, but also leading intellectuals of the day, such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu), and the first to focus attention upon the mechanical arts. Additionally, it was the first encyclopaedia in the French language, and was aimed at representing the thoughts of the Enlightenment. As such, this gave the work a political stance, for on several occasions it survived attempts at censorship by the Catholic Church, in addition to the removal of its royal licence in 1759.

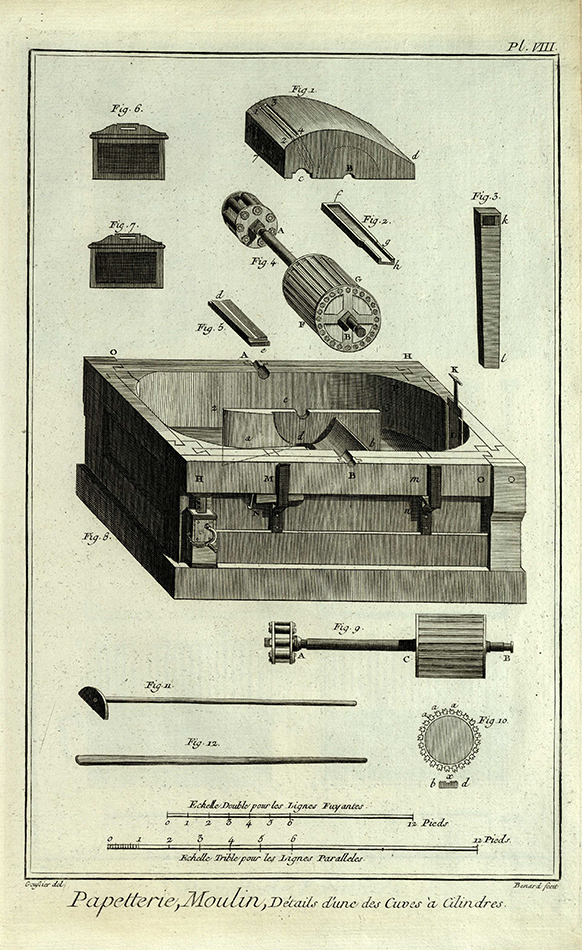

Published between 1751 and 1772 (although 7 volumes of supplements were published between 1776 and 1780), the Encyclopédie consists of 28 volumes, 17 of which are text, published over 15 years and containing over 71,000 articles. The remaining 11 volumes contain the illustrations, of which there are over 2,500, and which complement the text so crucially.

Although the plates were originally intended to be published alongside the text volumes, it was not until 1762 that the first volume was published, due to subscription and legal issues, with the final volume being published ten years later.

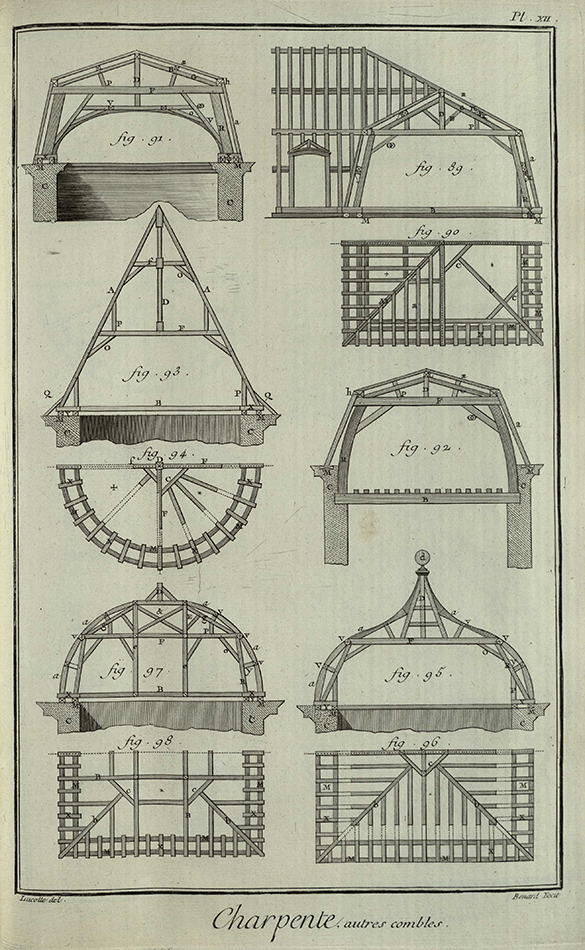

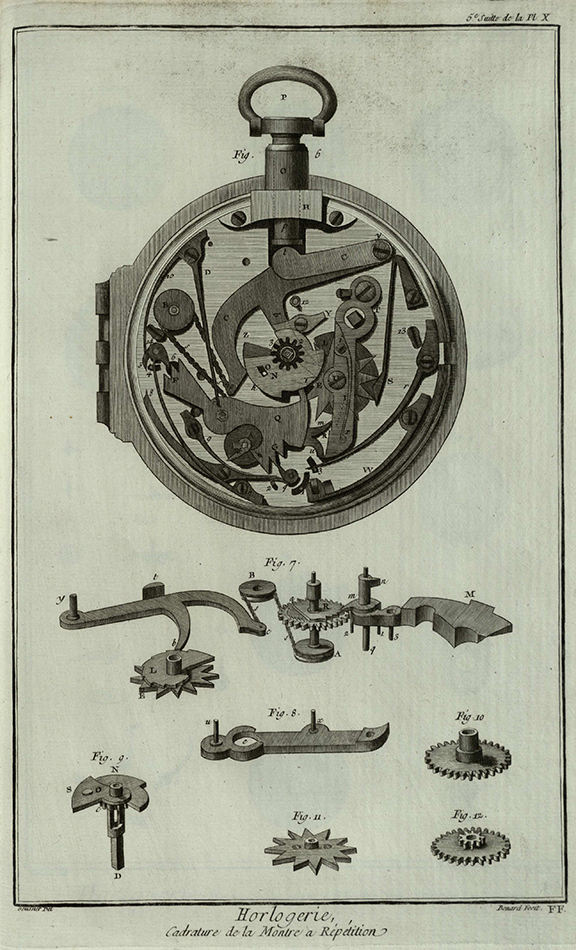

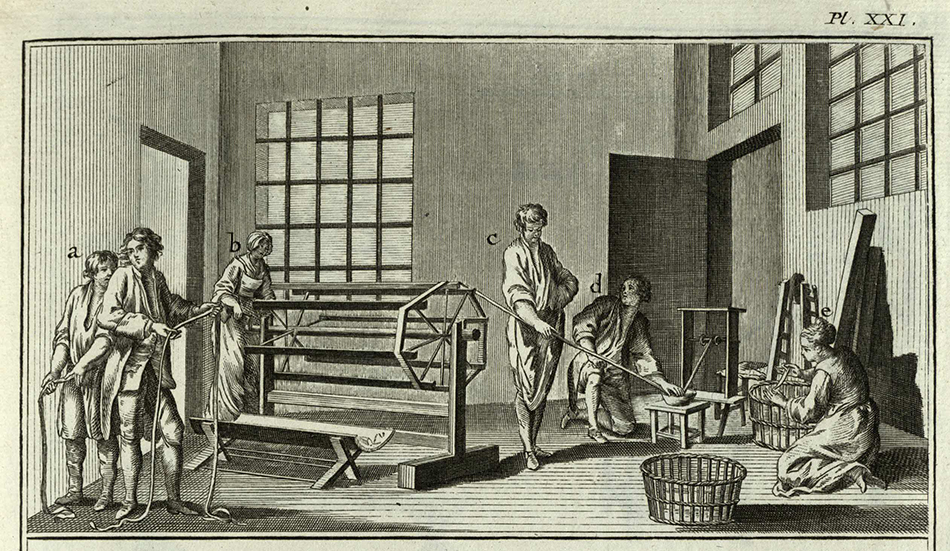

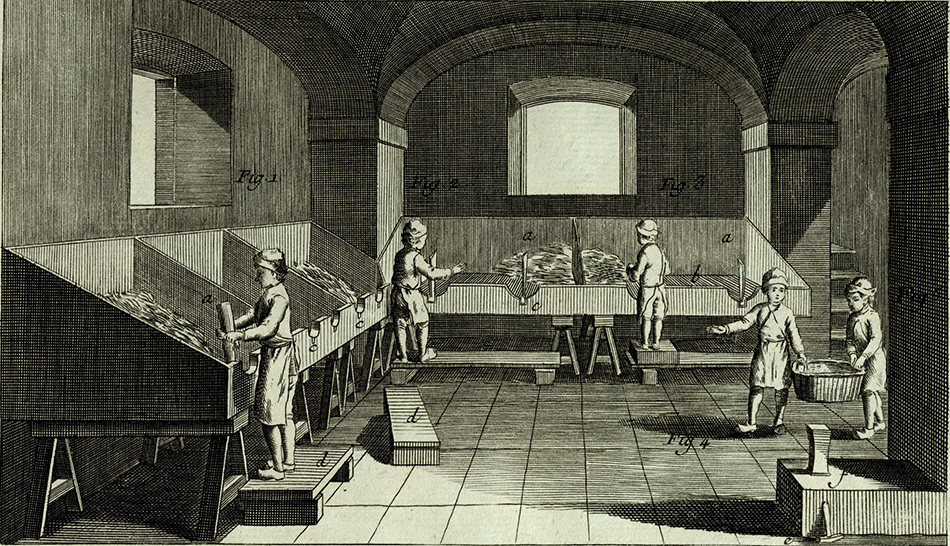

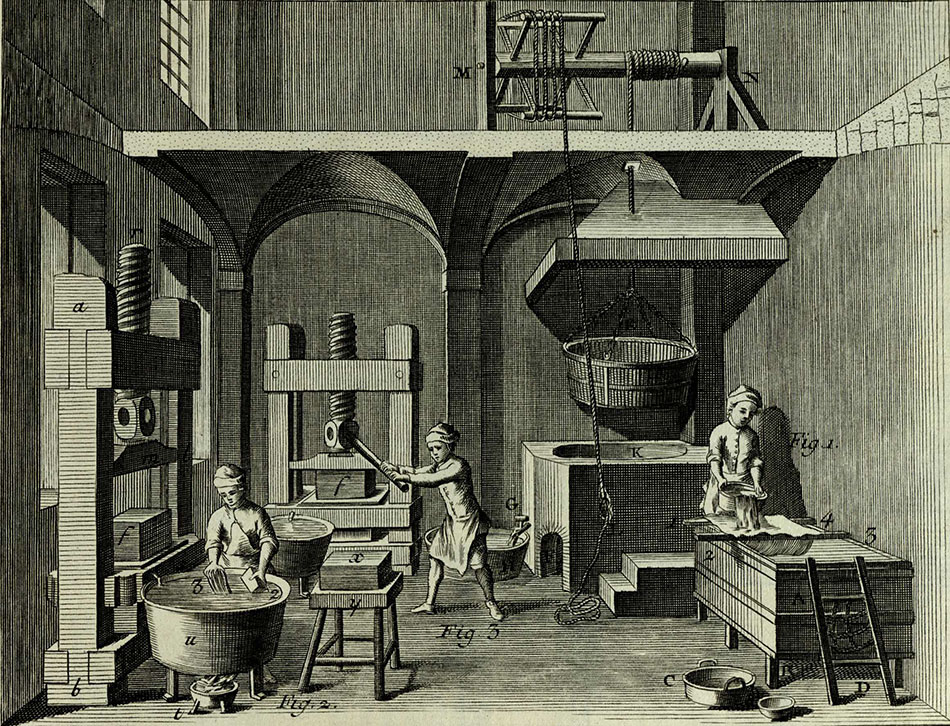

The plates are of a superior quality, largely thanks to the illustrator, Louis-Jacques Goussier (who holds the distinction of being the only illustrator to also contribute articles to the Encyclopédie). It had originally been intended that he merely redesign existing plates, but following a plagiarism suit against this redesign work, he created over 900 new plates. The designs are truly beautiful, but these plates are no less political than the text itself, for workshops are not presented objectively, but are rather shown as idealised spaces, ordered and clean, in an attempt to glorify the domestic manufacture of French products.

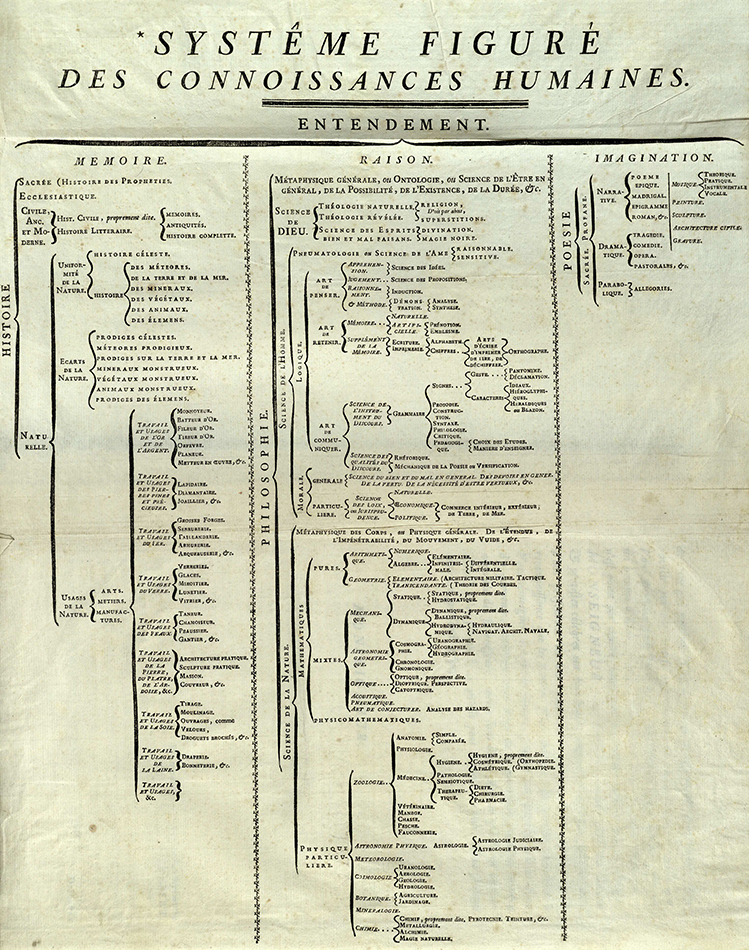

As with any encyclopaedia, Diderot and d’Alembert sought to collect knowledge which was disseminated around the globe so that it could be made accessible to one and all. Where this encyclopaedia differed to others was in the presentation of this information, for in the preliminary discourse (considered an important exposition of Enlightenment ideals), Diderot presents a tree of knowledge, organising the information contained within the Encyclopédie into three primary categories: Memory/History, Reason/Philosophy, and Imagination/Poetry.

A vast variety of processes are described in the Encyclopédie, but that which we chose to emulate is paper making. This comes under the heading Papeterie, a word which encompasses both the paper mill and the art of making paper (although the article itself is concerned with the latter, not the former). The author of the article, the illustrator Goussier, covered all aspects of the process as it would occur in a factory. Although the descriptions are clear to begin with (the first process being to separate according to weight the rags, which should be of linen or hemp rather than wool or cotton), the article soon becomes very technical, as Goussier loses himself in a detailed description of the machines which perform the various operations.

A simplified description of the process, however, is as follows. The rags were sorted by women before being left in a damp heap in order to rot (a process called retting in English) for two or three months according to the season. Next the rags were cut into small pieces by boys (a process which helped to purify the rags from dirt), before being beaten to a pulp by water-powered hammers.

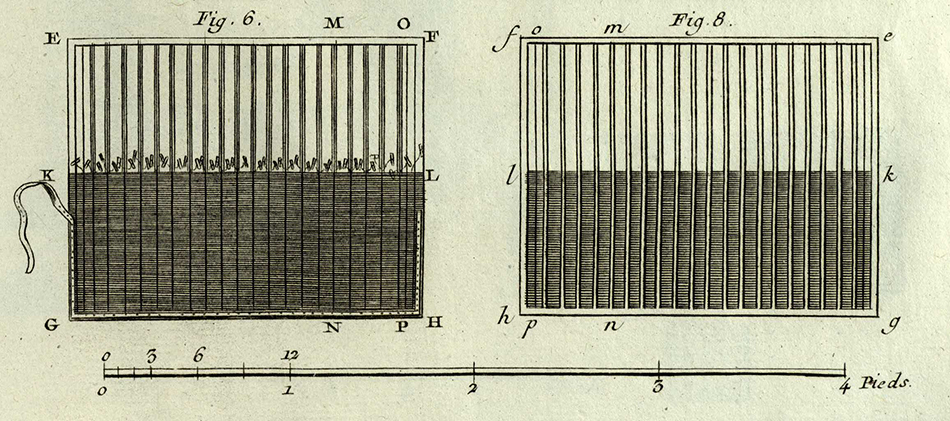

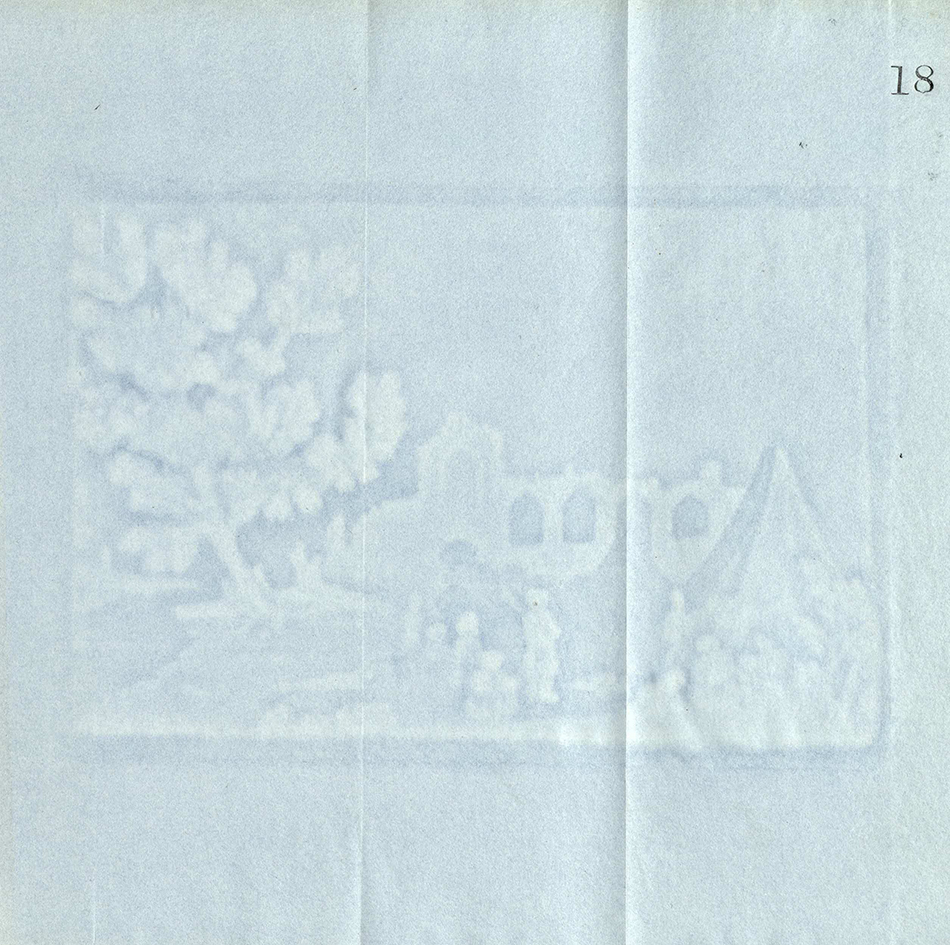

Another process which achieved the same effect was the rotary machine invented in Holland, which minced the rags into a pulp with revolving knives; Goussier includes a description of this Hollander beater. This pulp was then transferred to a vat, where the maker (or vatman – formaire is the French word) used a mould to lift out some of the pulp, shaking the mould first one way and then the other, to lock the fibres together and form a sheet of paper.

The mould, minus the deckle, was then passed to the coucher, who turned the sheet out on to a piece a felt, layering each alternatively. Once this ‘post’ was complete it was pressed to remove water, before the paper was removed from the felt and pressed again. The sheets were then hung to dry, before being ‘sized’, that is, dipped in to a solution of animal gelatine made by boiling the shavings of animal skins which came from tanners and parchment makers to which was added alum and copperas, in order to give the paper an impermeable surface. The sheets were then pressed and dried, before finally being scraped to remove knots and bumps.

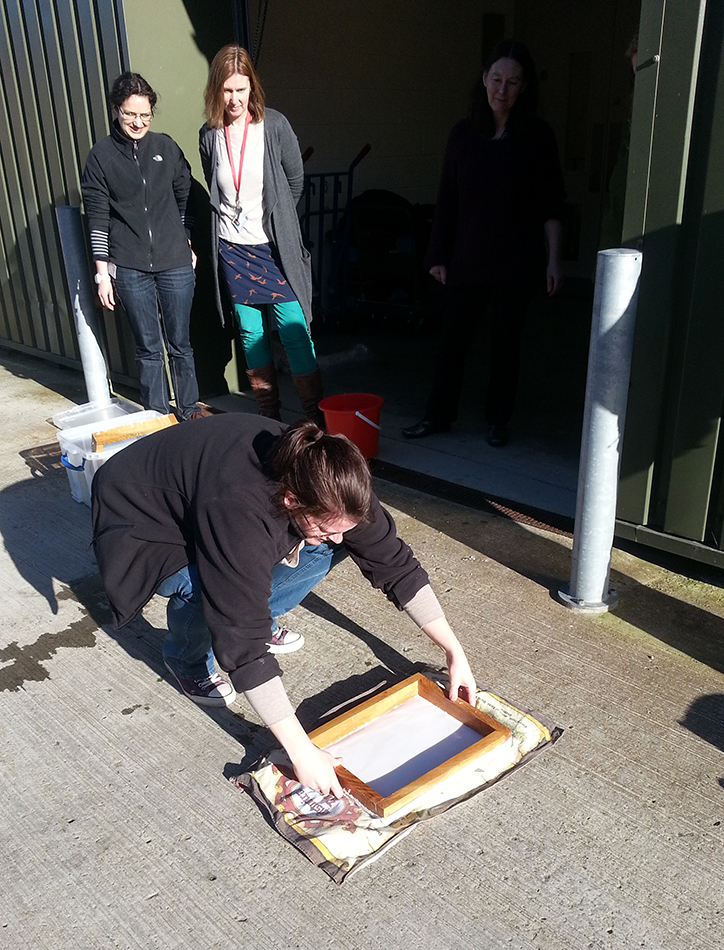

In our own way we attempted to replicate the paper making process. We didn’t use rags, but rather paper to form the pulp – but high quality paper which had originally been made from cotton! This was torn into small pieces and left to soak overnight, before being mulched to a pulp with hand-held blenders – our own homage to the Hollander beater, I guess you could say.

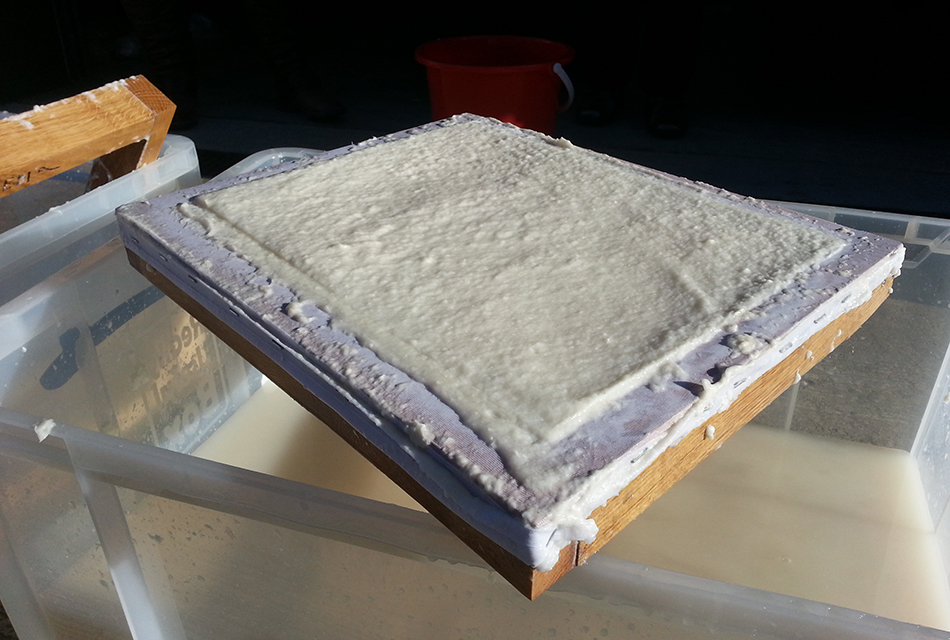

We then watered the pulp down to get a thinner consistency, and then we were ready to make paper. Eddie was wonderful, and had made us a mould and deckle from Fife oak. Attempting to get the right thickness of pulp on the frame was not as easy as expected, and the shaking in different directions to join the fibres together often resulted in the pulp sliding to one side. But after some practice we got the hang of it.

We then removed the deckle (although we later dispensed with this, finding it easier to just use the mould), and turned the sheet out on to a tea-towel (not having felt to hand) – these certainly provided some interesting textures to the sheets of paper.

The paper didn’t always want to come away from the netting (which may have been a little too fine), and although there were some casualties along the way, these were merely minor tears to the edges. We pressed excess water out after each sheet had been covered with a tea-towel, before giving a final press at the end. As we were unable to provide the pressure afforded by a paper press, we then left our stack to dry in a warm room.

As a final step, in preparation for the follow-up blog next week, we decided to size a couple sheets of the paper with gelatine. Sizing can be done with an assortment of substances from alum-rosin to rice starch; we chose gelatine as it was the easiest to source (the same stuff you find in the supermarket). This is done to limit the absorbency of the paper so the application of inks or paints will not spread quickly through the paper fibres, this is often called feathering.

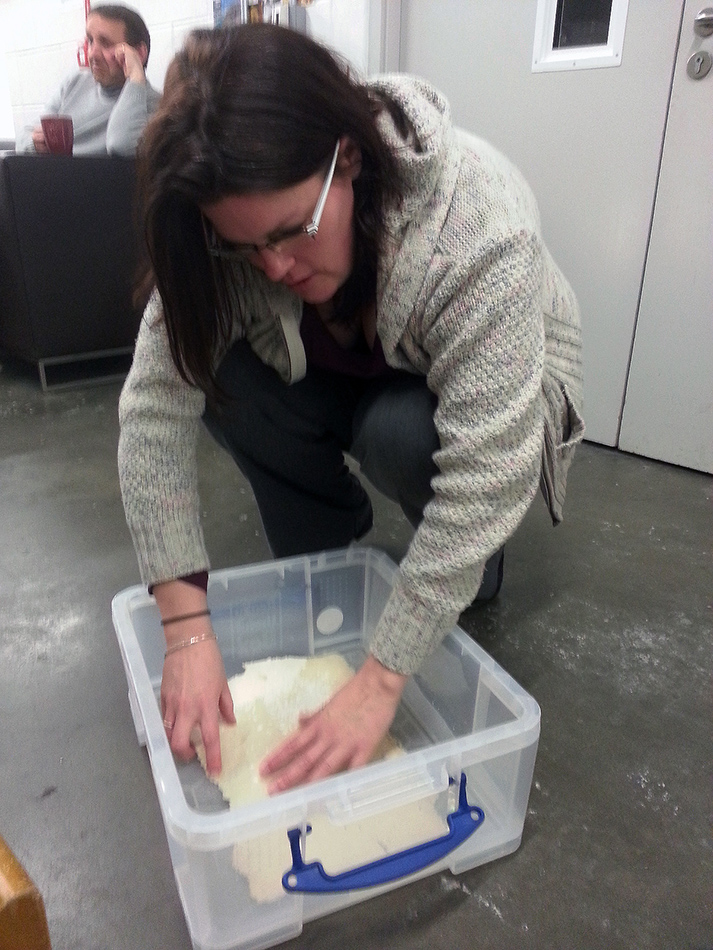

It took a few hours to dissolved 60 grams of gelatine in two litres of water, making a 3% solution. We warmed up our solution before putting it into a tub just a bit bigger than our paper. As the paper would be quite fragile after soaking in the sizing solution for a few minutes, we decided to use a sheet of woven polyester to support the paper before taking it out. We let it dry under slight pressure in hopes that it would be nice and flat, ready for next week’s Historical How-To.

Perhaps our results weren’t as fine as that which were described in Diderot’s Encyclopédie, but we had good fun experimenting, and gained a somewhat brief insight into the art of making paper; we can all certainly appreciate the skill of those artisans described in the Encyclopédie, and can recommend these volumes to anyone with an interest in the mechanical arts in France during the age of the Enlightenment.

BA, RN, EM, IF

Reblogged this on Behind the Spines and commented: The posts from Echoes from the Vault are always interesting and often very amusing. In this post, the art of papermaking is subjected to a practical experiment by staff from the University of St Andrews' Special Collections team.

[…] Browne’s instructions for cutting our own quills, we did make use of the iron gall ink and handmade paper that featured in the last two weeks’ posts. For the most part, the iron gall ink behaved much […]

[…] all the other people who have joined in communal activities such as the Halloween ghost tour, papermaking, the Christmas party, hillwalking, and the blog […]

[…] 52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 19: Diderot’s Encyclopédie and the art of making paper […]