Highlights from the Reading Room: Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth

As part of my research for Maria Edgeworth: A Political Biography (to be published by Pickering and Chatto in 2017), I have spent a few very pleasurable days reading the Memoirs of Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1820), enjoying SAUL’s lovely new Special Collections Reading Room in the Martyr’s Kirk building on North Street. It’s a big improvement on the chilly depths of the old Library basement: a comfortable temperature, with natural light, big desks, good chairs, a quiet atmosphere. But no improvement was needed to the staff of Special Collections: we’re lucky to have them.

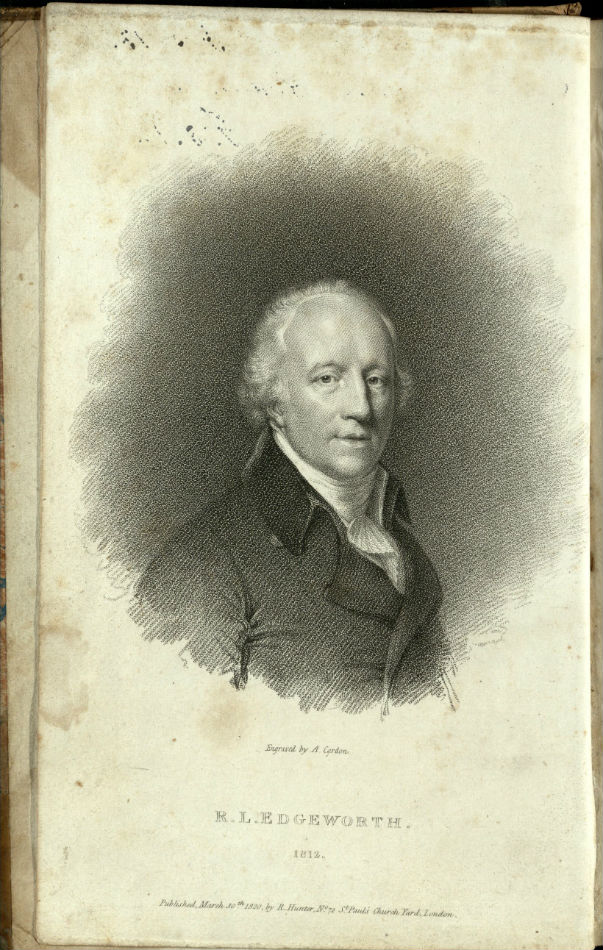

The Memoirs are a game of two halves: a rollicking first volume written by Richard Lovell Edgeworth himself – full of bizarre and entertaining events and stories from RLE’s younger days – and a much more sombre second volume, by his daughter, the celebrated Irish novelist and pioneer of children’s literature, Maria Edgeworth. (She promised she would complete his life-story after his death.) Volume One is illuminating as well as amusing, revealing the extent to which RLE connected benevolence – the wish to address others’ suffering or disadvantage and thus to create a better society – with invention. It suggests much about the emotional basis of his later devotion to the causes of mass education in Ireland and his mechanical projects (he invented an early version of the telegraph). Maria Edgeworth inherited this ethic of ‘liberality’, as the Edgeworths called it.

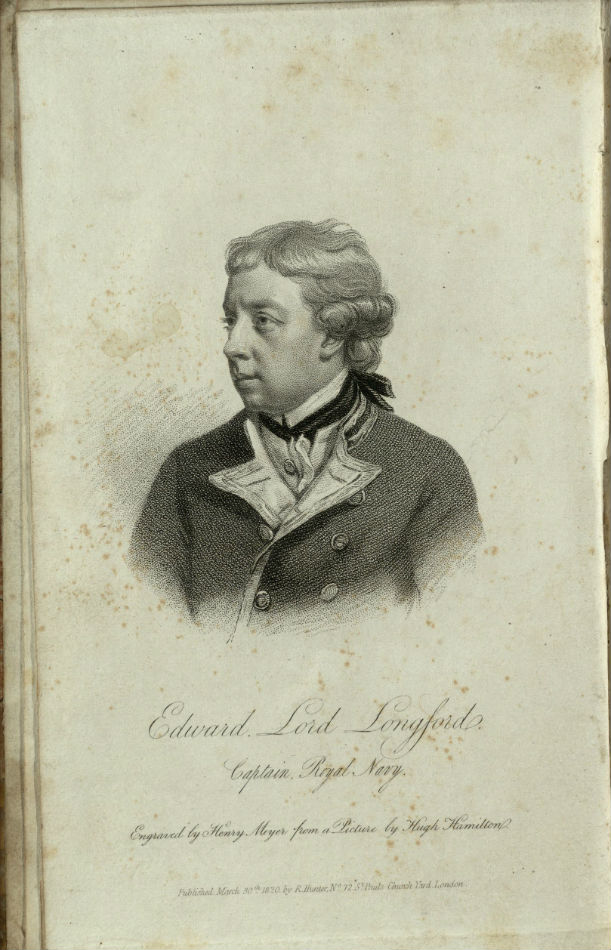

It was the second volume, however, that I was really there to read. It contains a full account of RLE’s Irish politics at a turbulent time: before, during and after the United Irishmen uprising and French invasion of 1798, and the heated debates about legislative union with Britain in 1799-1801. Maria Edgeworth regarded her father as her intellectual and literary partner: they collaborated on a number of works and he always offered editorial advice and criticism on her writing. It’s therefore important for me to absorb what she has to say about the family’s experiences during the 1798 rebellion, and in particular, her father’s reactions to the turmoil and to the work of improving Ireland’s political and social fortunes. She gives us a dramatic account of the Edgeworth family’s narrow escape from being blown up in a gunpowder accident during the 1798 uprising, and of RLE’s brush with death a few days later, assaulted by an Orange lynch-mob, who suspected him of having ‘illuminated’ Longford gaol for the benefit of the French invaders. RLE subsequently spoke and voted against Union with Britain in the Irish House of Commons – despite his conviction that Union would weaken the aristocratic monopoly on power, strengthen commercial and manufacturing enterprise in Ireland, and eventually lead to Catholic emancipation, which he had proposed as an important element of political reform in 1782. Maria also spends a good deal of time discussing RLE’s educational thought, which was strikingly secular and anti-sectarian, in contrast to contemporaries like Hannah More and Sarah Trimmer. The curriculum he proposed was modern, placing emphasis on the development of children’s autonomous and inventive powers of thought. The claims Maria made for RLE’s educational methods and ideology, together with some of the scandalous indiscretions documented in RLE’s first volume, meant that the Memoirs seriously damaged her reputation as an author: various critics in leading literary journals, especially the Quarterly Review, accused her and her father of being atheists, and questioned the morality of RLE’s modernizing, secular philosophy, and its echoes in her fiction.

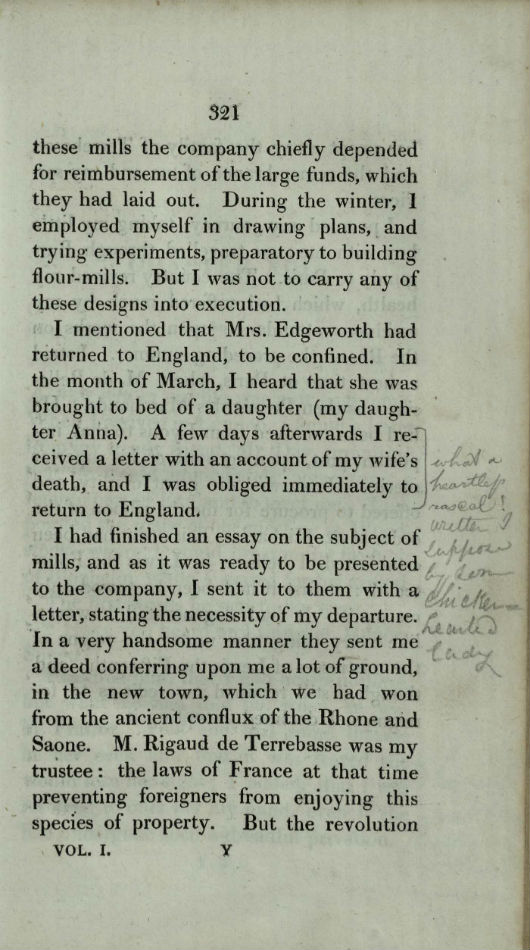

Alongside some tall tales – can RLE’s nurses in infancy really have been called Nurse Self and Nurse Evil? – RLE candidly recounts how he came to marry four times (or five, if – as some critics disingenuously claimed – a mock-marriage at an all-night party when RLE was still in his teens, using a door-key as a ring, was legally valid!). RLE’s cool account of his unloved first wife’s death on page 321 is followed on page 323 with his admission that he immediately proposed marriage to Honora Sneyd (having already frankly confessed that he had fallen in love with her some months before). He remarried within weeks of the funeral. Two early readers of SAUL’s copy remark in pencil in the margin, ‘his wife just immediately dead!’ and ‘what a heartless rascal!’. A third sneers, ‘written I suppose by some chicken-hearted lady’. It’s fun to see the outraged and sarcastic marginalia, but the adverse comments are also telling. They echo the pious shock of early critics, especially as RLE goes on to document how he married Honora’s sister Elizabeth (wife number 3) within months of Honora’s death from TB – and remarried a fourth time, again indecently quickly, when Elizabeth succumbed to the same malady in 1798. (At this point in SAUL’s copy, an exasperated reader grumbles, ‘I suppose he will have another 2 or 3 wives before the book is finished’.)

John Wilson Croker’s vicious review of the Memoirs in the Quarterly Review used the evidence of RLE’s exuberant sexual energies and lack of care for nice proprieties to suggest that readers should be wary of considering his daughter’s work as morally irreproachable. Although Maria told concerned friends that she hadn’t taken the attack on her father’s reputation to heart, it did affect her productivity and her willingness to re-enter the public world of print culture. After 1820, she published only one full-length novel, Helen (1834), part of which deals with the effects on a young woman of slander and the mischievous publication of the details of private lives.

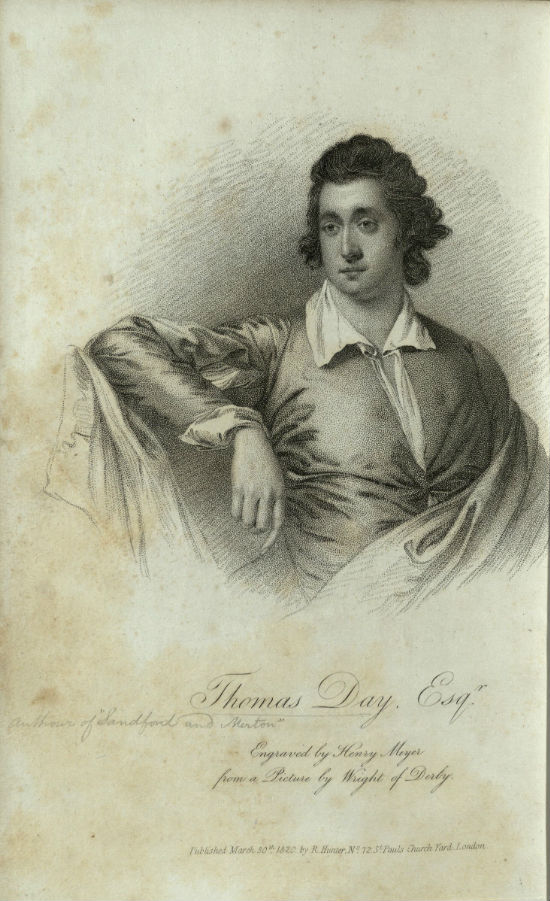

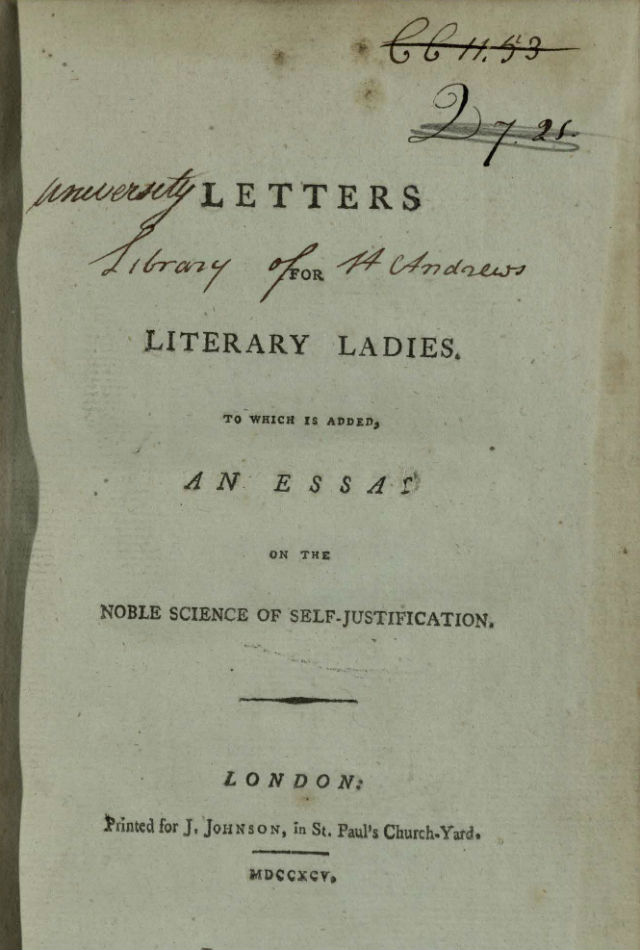

Oddly, the male critics who were so scandalized by RLE’s evident pleasure in the joys of marriage and by his progressive educational ideas had nothing to say in response to his revelations (in Volume One of the Memoirs) about Thomas Day, RLE’s best friend until Day’s death in 1789. In a quest for the perfect wife, Day had adopted two small girls from a foundling hospital, renamed them, and brought them up single-handedly, with the intention of later marrying one of them. To ensure that they could be moulded to resemble his ideal woman, Day took the girls to France, teaching them nothing of the language, so that they were open only to his influence. The project failed. Neither proved marriageable in Day’s eyes, and he dismissed the ‘invincibly stupid’ girls in their teens, giving them each money to marry or set up in business. Nowadays we’d think Day’s plan perilously close to ‘grooming’; at the very least it seems naïve and distasteful. Maria Edgeworth herself clearly thought so. She smuggled an extended satire on Day’s scheme into one of her feminist novels (Belinda, 1801), and sent up Day’s limited sense of appropriate female education in her tongue-in-cheek Letters for Literary Ladies (SAUL Special Collections has the rare first edition of 1795).

This in fact is what’s so fascinating about Maria Edgeworth’s fiction: again and again she takes material from the lives around her, and from the philosophical, political and scientific hot topics of the day, and works them into the plots, characters, and very texture of her narratives. The prim, piously father-worshipping daughter of the popular imagination was in reality a wickedly clever and subtle critic of contemporary mores and unquestioned prejudices, especially male ones. Thanks to Special Collections, we can uncover some of her sources and see how she went about creating her witty political fictions.

Susan Manly, School of English, St Andrews.

Great! So nice to find another image of Thomas Day...having read The Lunar Men I was familiar with him and this very strange story. He was likewise an oddity!

[…] ability to represent the ‘current of ordinary life’, but also by fellow female writers Maria Edgeworth and Mary Russell Mitford. Yet even so, her popularity with an increasingly vast body of readers […]