52 Weeks of Historical How-To’s, Week 22: An experiment in early 19th century hen-keeping

When I told my flock of hens they were going to take part in a Historical How-To and be fed an early 19th c poultry diet for a week, they were delighted. No more layers pellets they thought at once, mmmm. They are rather spoilt, living in the back garden and being fed tasty scraps regularly. But they also get a proper balanced diet of commercial layers pellets full of nutritious blends of healthy grains, minerals and vitamins, and so of course these are not popular.

I based my regime on two kinds of books on poultry keeping available in Special Collections. The first are books on cottage economy, written to help improve the living standards of the rural labouring classes, such as William Cobbett’s Cottage economy: containing information relative to the brewing of beer, making of bread, keeping of cows, pigs, bees, ewes, goats, poultry and rabbits, and relative to other matters deemed useful in the conducting of the affairs of a labourer’s family (1822), Esther Hewlett’s Cottage Comforts: with hints for promoting them, gleaned from experience; enlivened with authentic anecdotes (1830) and The cottager’s agricultural companion; comprising a complete system of cottage agriculture: intended to instruct the poor of Great Britain in the best arts of cottage husbandry by William Salisbury (1822).

These were immensely popular, Cobbett’s selling over 30,000 pamphlets and Hewlett’s book running to 8 editions. Many such self-help books were written by women, aiming to make poor farm labourers self-sufficient as far as possible.

William Cobbett (1763-1835), famous for his later book, Rural Rides, here gives his attention to trying to improve the life of smallholders and farm labourers. He thought the ordinary working family deserved a decent life in return for their hard work.

It is to blaspheme God to suppose, that he created men to be miserable, to hunger, thirst, and perish with cold, in the midst of that abundance which is the fruit of their own labour.

He wanted to show how to raise most of their food needs from a small piece of land through good management of the resources available to them. Practical advice for keeping cows, sheep, bees, chickens and encouraging them to make their own bread and beer, the staples of their diet, would enable them to feed themselves, with supplements of dairy products, eggs, honey, occasional meat, and have surplus livestock and produce to sell. Keeping a few hens would be very important part of this, providing both meat and eggs for very little cost.

Esther Hewlett (1786-1851) was the author of numerous religious and moral tracts. Her Cottage Comforts is more didactic, wishing to improve the moral characters of the rural poor in part by improvement in their living conditions and diet. She was concerned that they should be respectable and comfortable, with ‘decent habitation, wholesome food and suitable raiment’ but also stated that their well-being depended on themselves, their own exertions and their own management.

Topics include choosing a cottage to rent, cookery, management of household income, gardening, illnesses, pregnancy and child rearing, suitable books for the cottage library (good edifying titles), education of children and good neighbourliness, as well as animal husbandry.

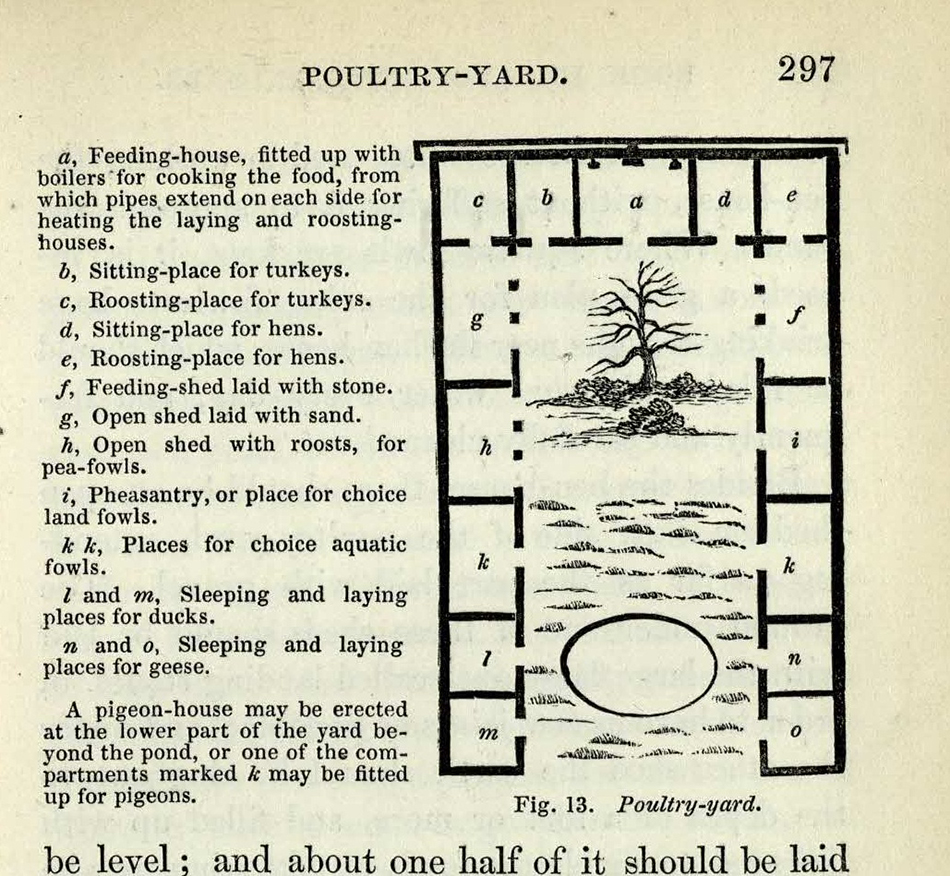

The second kind of book proffers advice to the better off on household management and roles of servants. This would include the dairy-maid who often was in charge of poultry as well. Examples of this genre are Mrs Jane Loudon’s Lady’s Country Companion of 1845, An encyclopædia of domestic economy by Thomas Webster and Mrs. Parkes, published in 1844, Practical economy: or, the application of modern discoveries to the purposes of domestic life by Henry Colburn, 1821 and The servants’ guide and family manual by John Limbird (1830). These deal with a much grander scheme of hen-keeping involving poultry yards and special henhouses for the flock, and keeping other kinds of fowl such as turkeys, geese, ducks and even guinea-fowl.

The self-help manuals give advice and instruction on hatching and rearing hens, best varieties to keep for eggs and for meat, what to feed them, how to house and protect them from the weather, vermin and illnesses. I tried to take from them a regime for hen keeping which I could apply to my own birds.

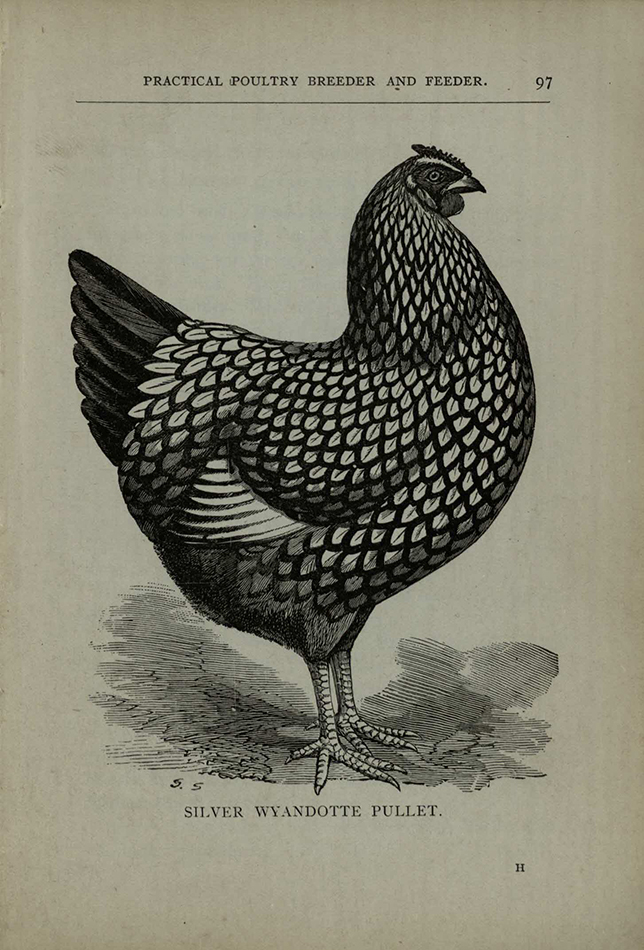

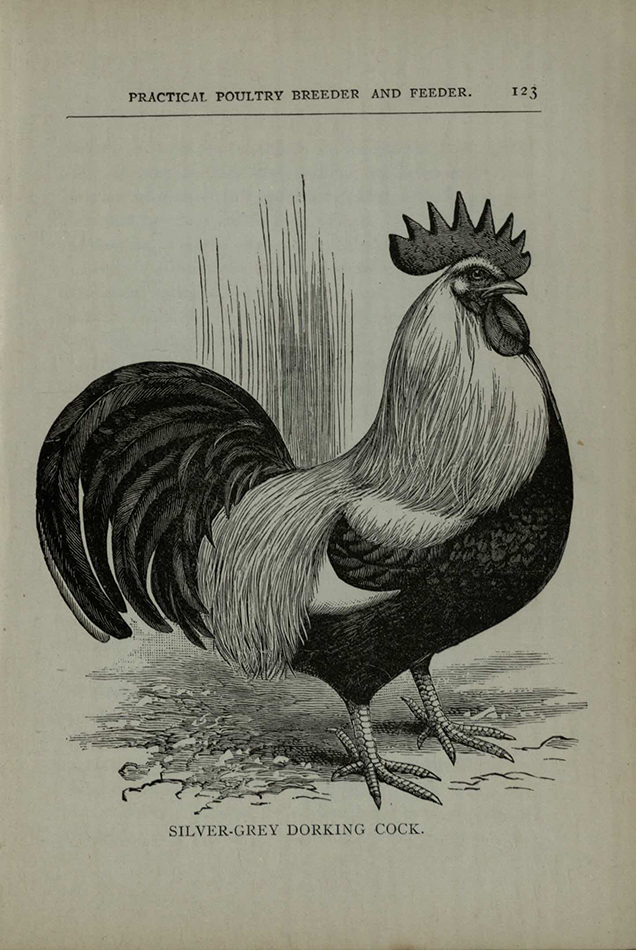

Breeds

Most of my hens are from breeds introduced later in the 19th century, such as the Wyandotte. The most common kind around 1800 was a general purpose barn door or dunghill hen of no particular pedigree, which looked after itself and foraged around the farmyard. Light coloured fowls were considered best for the table, and dark hens were best for eggs. Of the specific breeds mentioned in these books, I have a silver grey Dorking, called Grace, and some Pekin bantams, but none of the Malay, Cochin, Brahma, Dutch fowls, game fowl, crested or Polish hens also mentioned. My hens are not so much barn door as back door hens.

Feeding

I took elements from all these books and tried them out on my own hens. There is much discussion on the best diets to fatten hens and to improve egg yields, especially to get them to lay in winter. The Encyclopaedia advocated warm roast potatoes 3-4 times a day! I economised with boiled potatoes as advised by several other authors, but even these were met with contempt by the hens. They had seen through my cheap as chips way to fatten them for the pot and were having none of it.

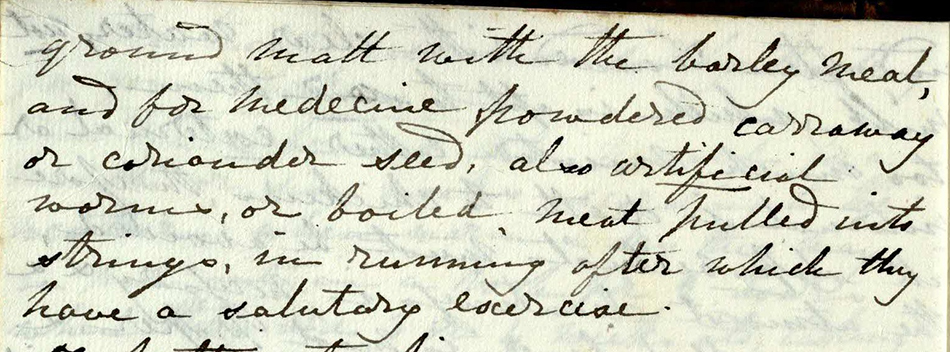

ground malt with the barley meal, and for medecine powdered carraway or coriander seed, also artificial worms, or boiled meat pulled into strings, in running after which they have a salutary exercise.

A manuscript notebook from around 1800 (msHD9282.B2) advocates feeding artificial worms made by pulling from meat, so I thought lardons would be a suitable modern equivalent – they went down so fast I couldn’t even get the camera ready before they were gone. Curds, recommended by a number of authors, also went down very well.

Various kinds of grain were traditional foodstuffs for hens in the early 19th c, so I tested out preferences, following Reamur’s notes on types of grain likely to be useful. He didn’t find much preference for one kind over another but my hens certainly made their preferences plain.

I first offered them raw grain – they normally get wheat but I also tried kibbled maize, buckwheat, 3 forms of barley (pot, pearl and flaked), flaked rye and oats. All the barley was very popular. No one wanted the rye or the oats, and the buckwheat was not popular until the small bantams and Pekins found it – it’s much smaller than the other grains and so maybe more attractive to the tiny breeds.

Then I cooked up all these grains and put them out – many books advocate cooking the grain as it speeds up digestion and so helps fatten the birds faster. Here it was noticeable that hens would wander between plates more, trying each one – maybe because they don’t ever get cooked grain and so were curious. In the end the oat porridge proved very popular indeed and was soon gone. Again no-one wanted the rye flakes, but barley and wheat were well received.

On the whole they were not very excited about this new choice in grain. However when I took a mixed batch of leftovers to my other group of hens, well known to be voracious eaters, they just fell on them and scoffed it all up without pausing to consider the flavours.

Suggestions for feeding boiled carrots, Swedish turnips, apples and cabbage I already do, and I also give the powdered oystershell for strong shells advocated by The Servant’s Guide.

Other recommendations for hens included beer, toasted bread sopped in wine (a French idea of course), rice boiled in milk with sugar, hempseed (from cannabis plants!), boiled dried nettles, and feeding them herbs which I know already my hens will turn their noses up at. Mrs Loudon even suggested leaving a bullock’s liver in part of the poultry yard to grow maggots – decided not to try that one.

Housing

Loudon gives instructions for a whole poultry yard, also describing the mischief hens can do if allowed liberty in a garden, by dust bathing in the flower beds and scratching up plants in the hunt for insects and worms. I know this to my cost.

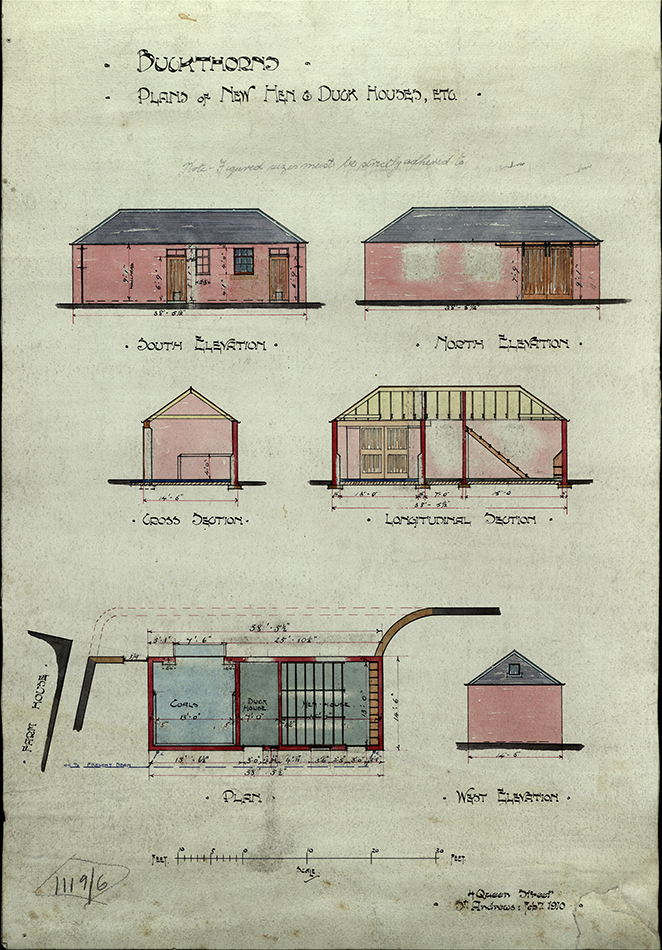

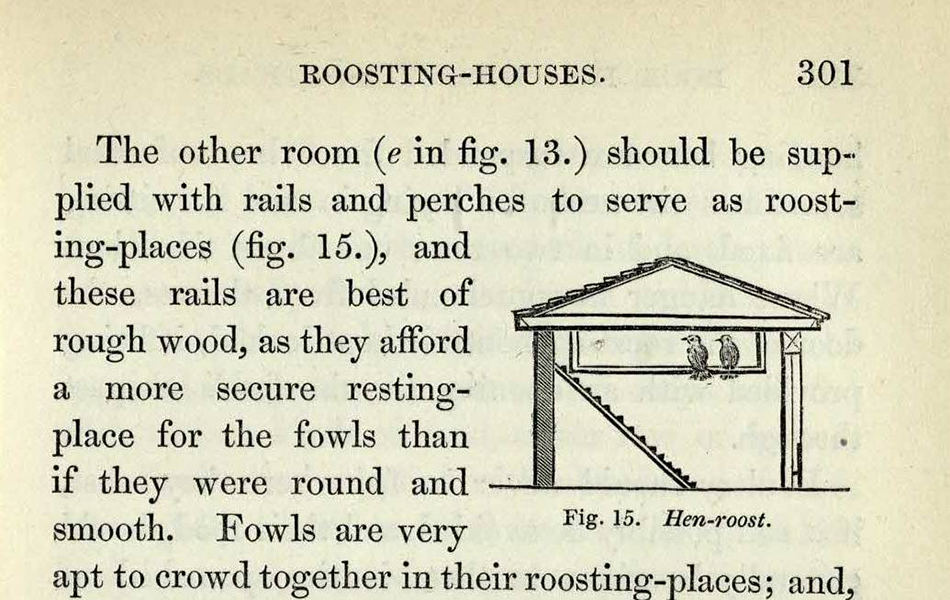

The Encyclopedia gives comprehensive instructions for the construction of the hen house, nesting boxes, perches and shelters. Loudon’s hen house design is pretty similar to mine and to the Gillespie and Scott plans for a new hen and duck house at Buckthorns farm near Upper Largo, dated 1910.

Cobbett advocated wicker baskets instead of wooden nesting boxes but my hens said no thanks to this innovation, agreeing with Hewlett that they were too draughty.

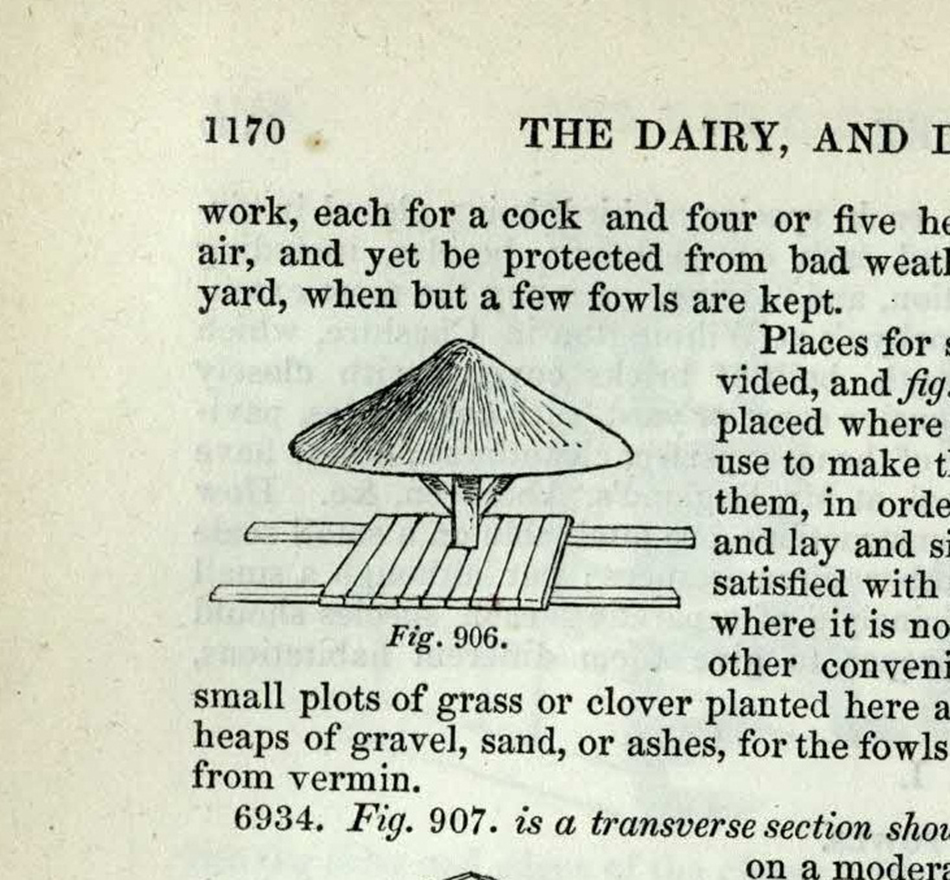

All the commentators have a great fear of wet weather, too much moisture both internally and externally being the most damaging conditions for hens. Some suggest not even letting them out in the rain but I knew I would have a rebellion on my hands if I tried that. The Encyclopaedia shows a portable shelter for when it is raining, and I include my own modern version of this.

They all stress the importance of cleanliness in the henhouse, with regular scrubbing out, yearly whitewashing, which is still thought to have anti-bacterial qualities today, and all dishes to be scrubbed daily, to prevent disease and keep the flock healthy. Loudon thought they should be fed from a large stone which could be scoured properly – I feed mind on paving stones too but that’s mainly to stop them raking up the grass lawn looking for titbits they might have missed.

The authors also recognised the importance of space and exercise:

fowls are never well unless they are allowed abundance of room for exercise

Loudon p296

Sand or ash should be provided for dust-bathing to remove lice and fleas – I offered them ash but my hens are much keener to use the nice soil in the flower beds for bathing.

Preservation of eggs

Various advice was given on how to extend the life of eggs especially through the winter. It was known that the eggshell was porous and let in air over time. Suggestions to prevent or reduce this include smearing in varnish, butter, oil, or mutton suet or dipping in gum Arabic, and then burying in bran, wood ashes, salt, charcoal powder, sawdust or shavings, but avoiding mahogany shavings which imparts too much flavour. Others suggest covering in lime-water, or dipping in oil of vitriol (sulphuric acid)! The eggs should last for 6 months or even a year!

I thought I would give this a go. So I took 4 eggs all laid on the same day, covered one in varnish, one in butter and one in cooking oil, and kept the 4th as a control egg. Then I put them away in an egg box for 4 weeks. Today I opened them all, as well as a freshly laid egg for comparison. You can see the results in the photo – the saucers contain the not very nice oiled egg on the left, and the horrible cloudy varnished egg on the right, which looks like it absorbed the varnish through the shell.

But the 3 at the front look quite similar with nicely rounded yolks and 2 of them have distinctly cohesive whites, all the signs of a nice fresh egg. The best looking one is in the middle – and is in fact the 4 week old buttered egg. The one on the left is actually the fresh one, and the right hand one is the control egg. So you can best preserve your eggs by covering them in butter, or by doing nothing at all. Maybe this isn’t a statistically significant result but it was fun.

It turns out that 19th c hen keeping is not very different from 21st century hobby hen keeping in terms of feeding, housing and health care. We were all following non-intensive practices which produce healthy happy hens. The horrors of modern industrial-scale battery hen farming are a monstrous invention not even dreamed of by the 19th c writers. They all condemned the practice of cooping up hens to fatten them, because the loss of liberty actually made the hens lose condition; and also the practice of cramming, forcing food down their gullets to speed up fattening – a method still used today in the production of pate de foi gras.

I am quite sure you would not suffer any creatures under your control to be subjected to such treatment

Loudon p304

My hens at least enjoyed being part of this week’s experiment, and are probably hoping for some more of those artificial worms.

-MS

Libraries and chickens in the same post - heaven!

What Fun. Brings back memories of our hens being fed during the war by coolking up all left overs including potato peelins.

As a small child during WW2, I can recall eggs being preserved in a bucket of some sort of liquid - except that often it did not work well and the eggs went bad anyway. What could that have been?

That was probably isinglass, made from swim-bladders of fish! Still used to preserve eggs into the 1960s.