MEI Internship Project Begins: a 16th century German binding mystery solved!

This summer, St Andrews began contributing information about its earliest printed books to CERL’s Material Evidence in Incunabula project. This project, initiated and directed by Dr Cristina Dondi, seeks to pull together all of the material evidence left by owners, booksellers, binders, and others appearing on all books printed prior to 1500. As an intern, I have begun the thrilling (and monumental) task of pulling together every mark found on St Andrews’ 150+ XVth century printed books.

The kind of research this project entails concerns the provenance of a book, which is to say its history of ownership. From clues like signatures, shelf marks, and bookplates, it is possible with some careful digging to discover where a book was before it came to its 21st century resting place.

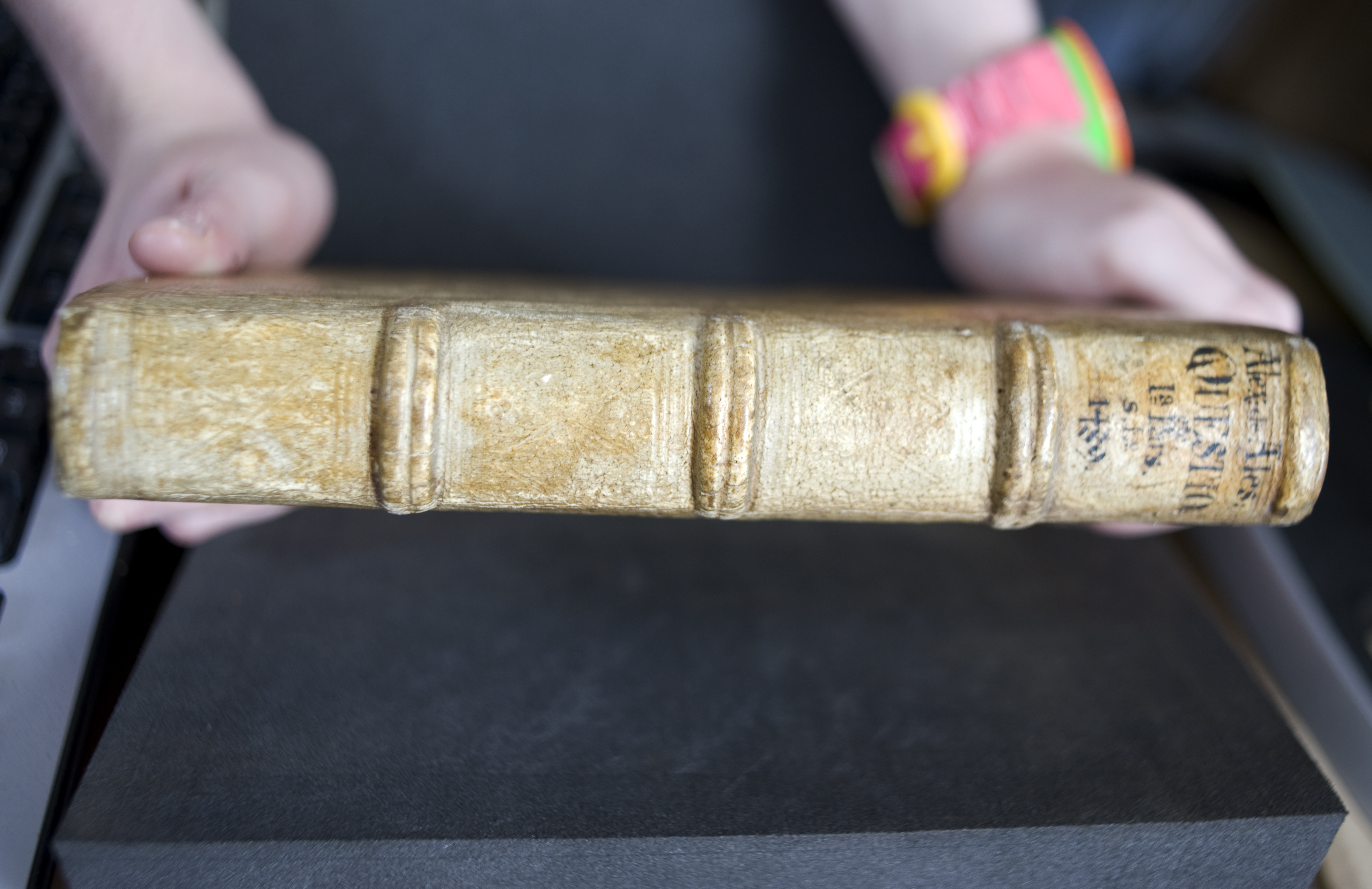

Some pieces of material evidence are easier to attribute than others. The record I have most recently completed, a 1489 Alexander de Ales Summa universae theologiae printed in Pavia, provides excellent examples of both.

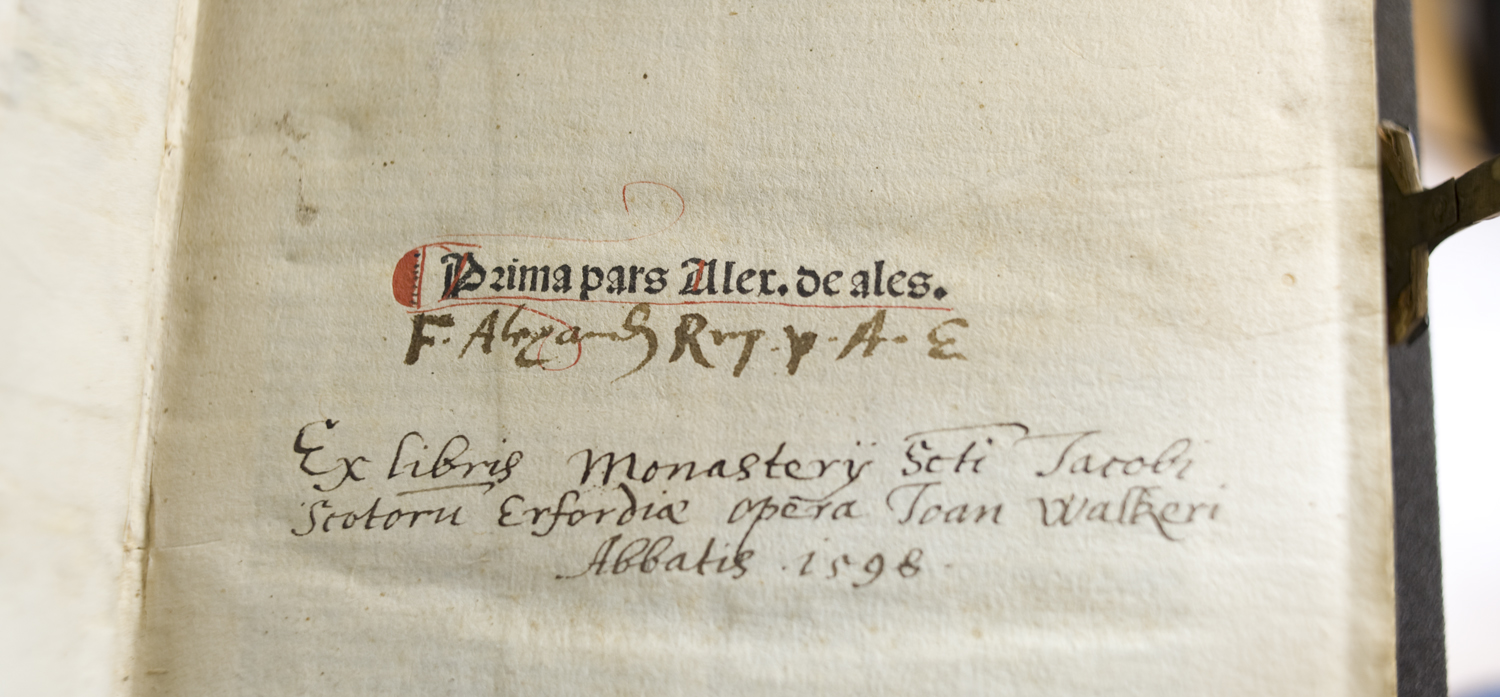

The title page bears two owners’ inscriptions, one of which is a dream for a cataloguer researching provenance. The hand writing of what I believe to be the later inscription is delightfully clear and fully legible, particularly to expert palaeographer Rachel Hart, who lent her talents to this part of the research. Furthermore, it answers nearly every question the MEI project poses about a piece of provenance: where was the book, when was it there, and who owned it?

From this piece of evidence, we know that the book existed in the St. James of the Scots monastery in Erfurt in 1598. The monastery was founded in 1136 by immigrants to Germany from Ireland and Scotland. By 1598, it had survived the turmoil of the Reformation and remained in operation until its absorption by the congregation of St Nicholaus in 1820. Although the book may not have stayed in the monastic library for that entire period, we can say with absolute certainty where it was at the end of the XVIth century!

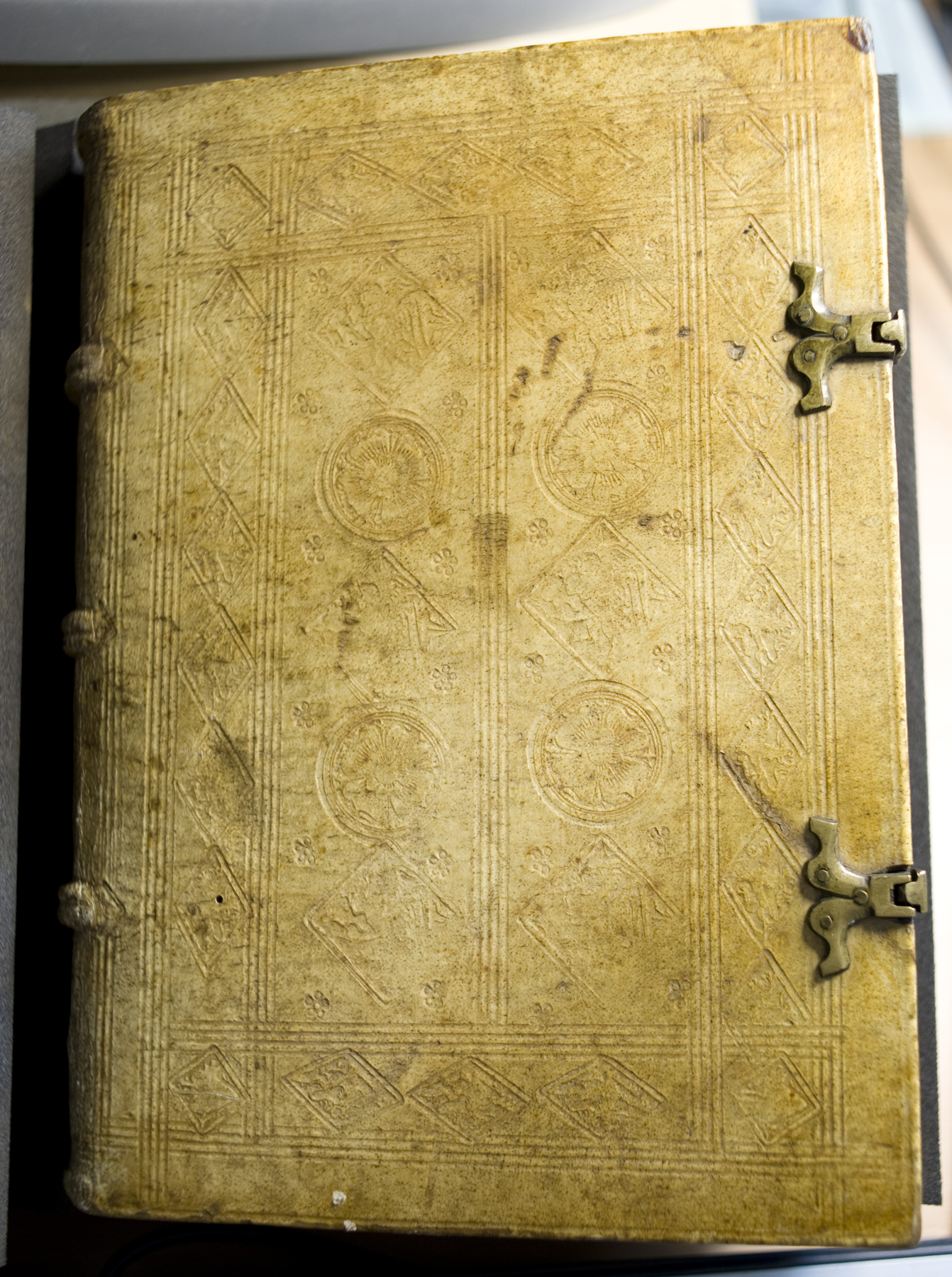

Prior to the 1598 inscription, attribution becomes more difficult and exciting. Tracing the binding in particular shows what provenance research can look like on the complicated end of the spectrum. The current binding had to have been done some time between the book’s printing in 1489 and acquisition by the monastery in 1598. However, determining the when, where, and who became a serious piece of detective work.

At a glance, this is a classic example of an early German binding: white pigskin on boards with decorative elements stamped in concentric rectangles and metal clasps fastening from back to front. While it is still technically possible for work like this to have been done in Italy, the distinctive regional style gives strong indications that this piece of material evidence is also German.

My next step involved examining the stamps used to decorate the binding in order to trace the work to a specific workshop. In the incunabula period, binders largely created or commissioned their own, unique tools, much like early printers did with typefaces. The most distinctive of these tools are the metal stamps, which were used either alone or in patterns to create relief designs on a binding. For provenance research into XV and XVIth century bookbindings, finding the stamp generally means finding the binder.

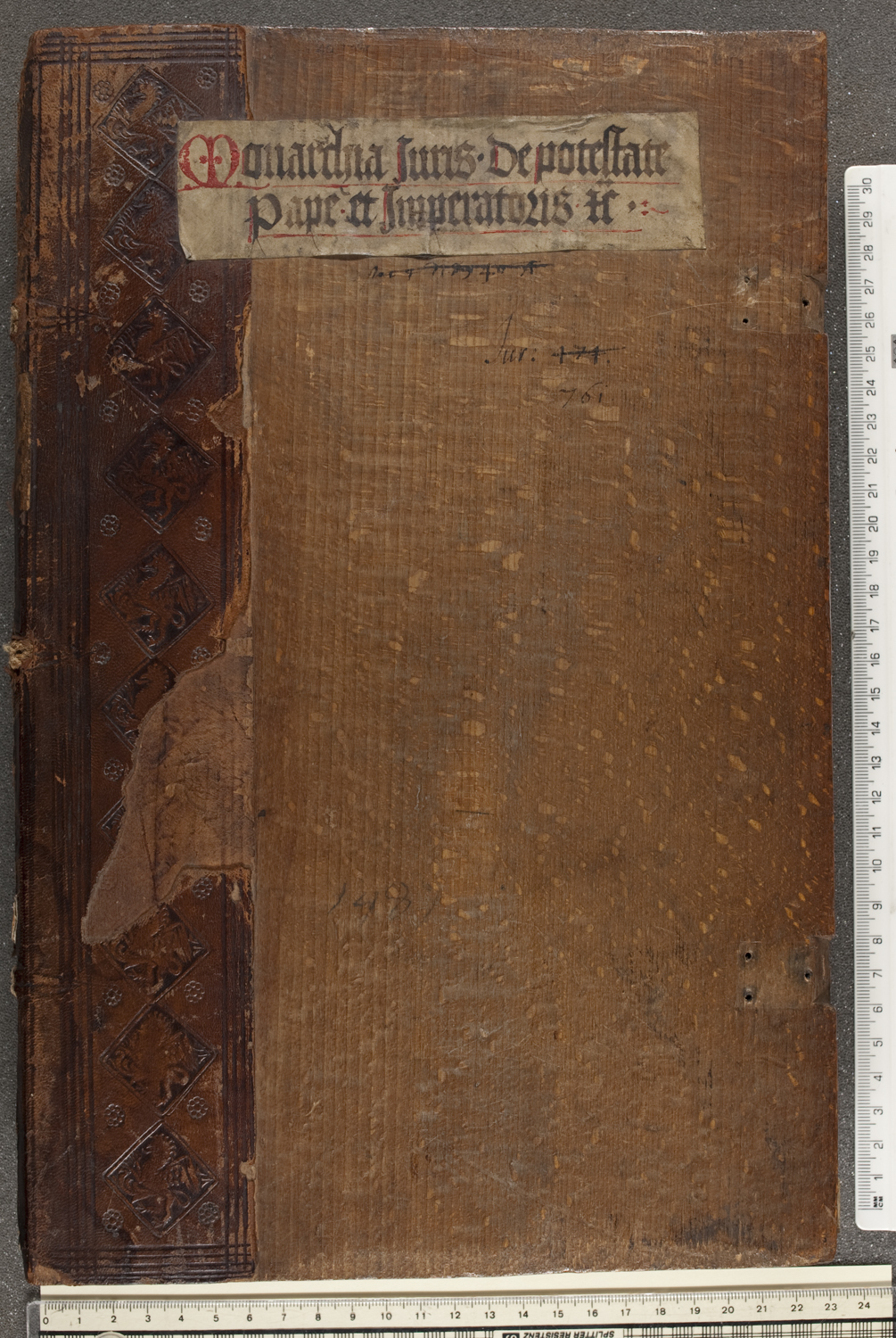

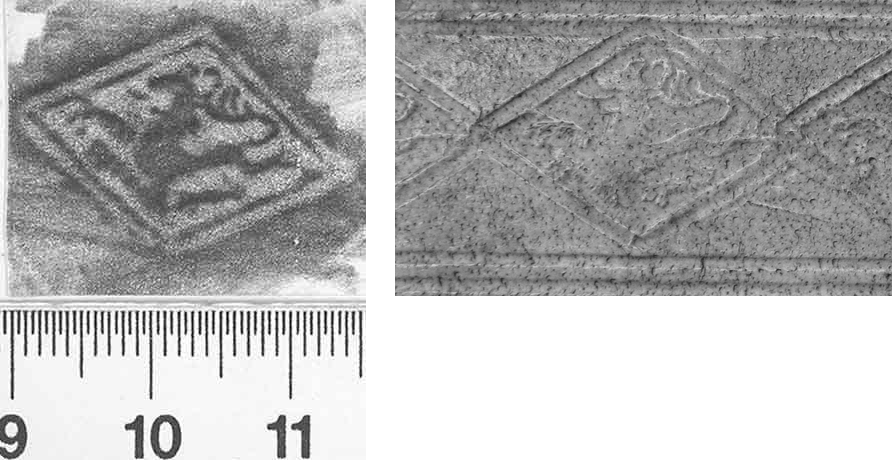

I began with what seemed to me the most unique of the stamps: a griffin rampant in a single, diamond-shaped border. Initially, it suggested a resemblance to another griffin appearing on a German binding of an incunable also belonging to the University. This volume belonged to Hartmann Schedel, author of the famous Nuremberg Chronicle, and was bound by his binder in Nuremberg (TypGN.A81KD)

Had the stamps matched, my search might have ended there. However, not only are the two griffins slightly different, but none of the other stamps on my German/Italian mystery appear on the Nuremberg binding. Though the similarity of the griffins seemed a comforting sign that the binder was, in fact, German, I had to go back to the drawing board to trace it to a workshop.

The next step was to attempt a visual confirmation that at least two of my stamps matched those on a binding held at another library. This was an enormous challenge, given that a true confirmation can only be made if the other library provided a sufficiently high-quality image, exact measurements, and a way to search through bindings.

My first stop was the British Library, which provides a searchable database of bookbindings. After peering at thumbnails of XV and XVIth century German bindings, I found another possible match for my griffin from an Anton Koberger imprint bound at a Nuremberg bindery (BL IB7316). Sadly, I was again left without sufficient evidence to make a clear confirmation.

A look through W. H. James Weale’s 1922 catalogue of Early Stamped Bookbindings in the British Museum did not result in any confident matches. Neither did the images in Mirjam Foot’s excellent publications on bookbindings.

After having no luck with English-language sources, I turned to the Einbanddatenbank hosted by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. This enormous database enables users to search through rubbings taken from XV and XVIth century German bindings, aggregated from several library holdings and traced, where possible, to specific workshops. One great benefit of rubbings is that the images they give are fairly clear and do not depend on raking light to show relief images.

I began by restricting my search based on the dimensions of each stamp, as I rapidly realized that the motifs depicted were all fairly popular. The griffin and rosette stamps both gave several near matches to different binderies in southern Germany. The records EBDB provided for these workshops showed that many of them used both rose and griffin stamps – still not enough for me to definitively point to one workshop.

On the 14th page of thumbnails of small stamps depicting a lion rampant inside a diamond border, an almost unmistakable match caught my eye. Furthermore, EBDB placed the stamp in Erfurt, just like my certain piece of material evidence. The rubbings come from a book at the Herzog August Bibliothek at Wolfenbüttel, call number S 248.2* Helmst. In addition to the lion, this book bears a griffin rampant stamp, a rosette stamp, and, most tellingly, a small stamp of a heart pierced by an arrow.

Bettina Wagner, who kindly directed me to the binding from which the rubbings were taken and clarified some confusion over possible matches for the binder, gave me the final pieces of information I needed. This bindery was in the Augustinian monastery at Erfurt where Martin Luther lived from 1505 to 1511, and operated through the second decade of the XVIth century.

I was then able to record in MEI with confidence that St Andrews’ classmark TypIP.A89BA had left Italy for Erfurt ca. 1500, and very likely remained there for the duration of the century!

This record is one of the very first that I have created as a part of my adventure among the incunabula. When I inevitably run into other fun and interesting puzzles, I will share them here!

–Jamie Cumby

MEI Intern

Great detective work, Jamie!

congratulations , Jamie

Excellent work. Thank you for sharing!

[…] was therefore terribly exciting to come across a blog-post from the University of St Andrews Special Collections team about their contributions to a new CERL […]