Considerations Upon the Union… “from the will and humour of the people”

As we approach the fevered climax of the Scottish independence referendum, we thought it would be interesting to compare this situation with the debate surrounding the mirror-image of this referendum, when the Articles of Union were under discussion by the Scottish parliament in late 1706.

A particularly striking feature of the current debate, of course, is that it has been marked by an almost unheard-of engagement of the people in the street. There is realistic expectation of an extraordinarily high turn-out at the polls; for once, the debate seems almost to have been lifted out of the hands (or mouths) of the politicians, and is being conducted on the street corner, in the workplace, in pubs and coffee shops. People seem not to be following slavish adherence to party, but are individually informed, and are making personal decisions based on those issues which matter to them most. This is possible today because of the ease with which people can educate themselves on the points at issue. Especially in the last few weeks, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and many others have been in the front line of the struggle for votes.

Obviously, there is one overwhelming difference between the two debates. There may have been public discussion in 1706, and the mob was an ever-present threat; but the masses had no say in the matter, and the writing of the period was aimed not at the ‘person-in-the-street’, but at the ‘man-in-the-parliament’, or at least at those in that small portion of society which might have any influence.

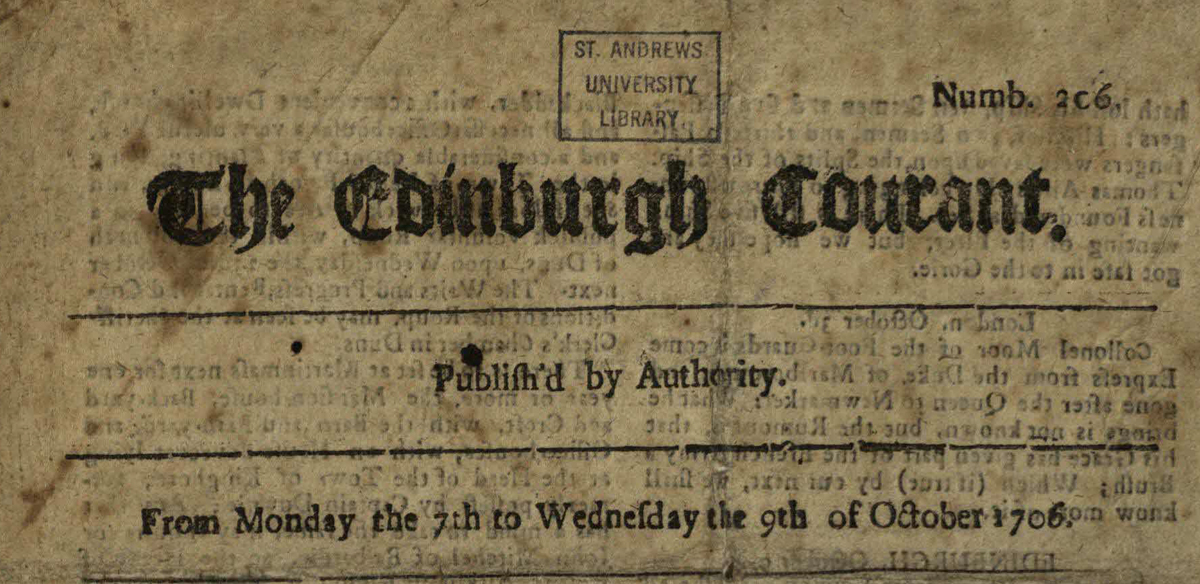

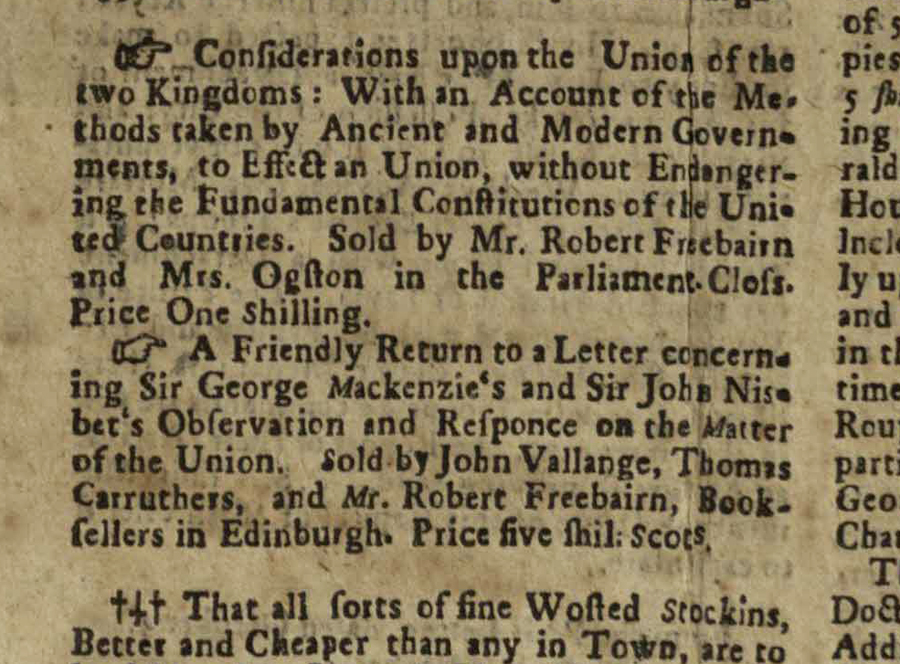

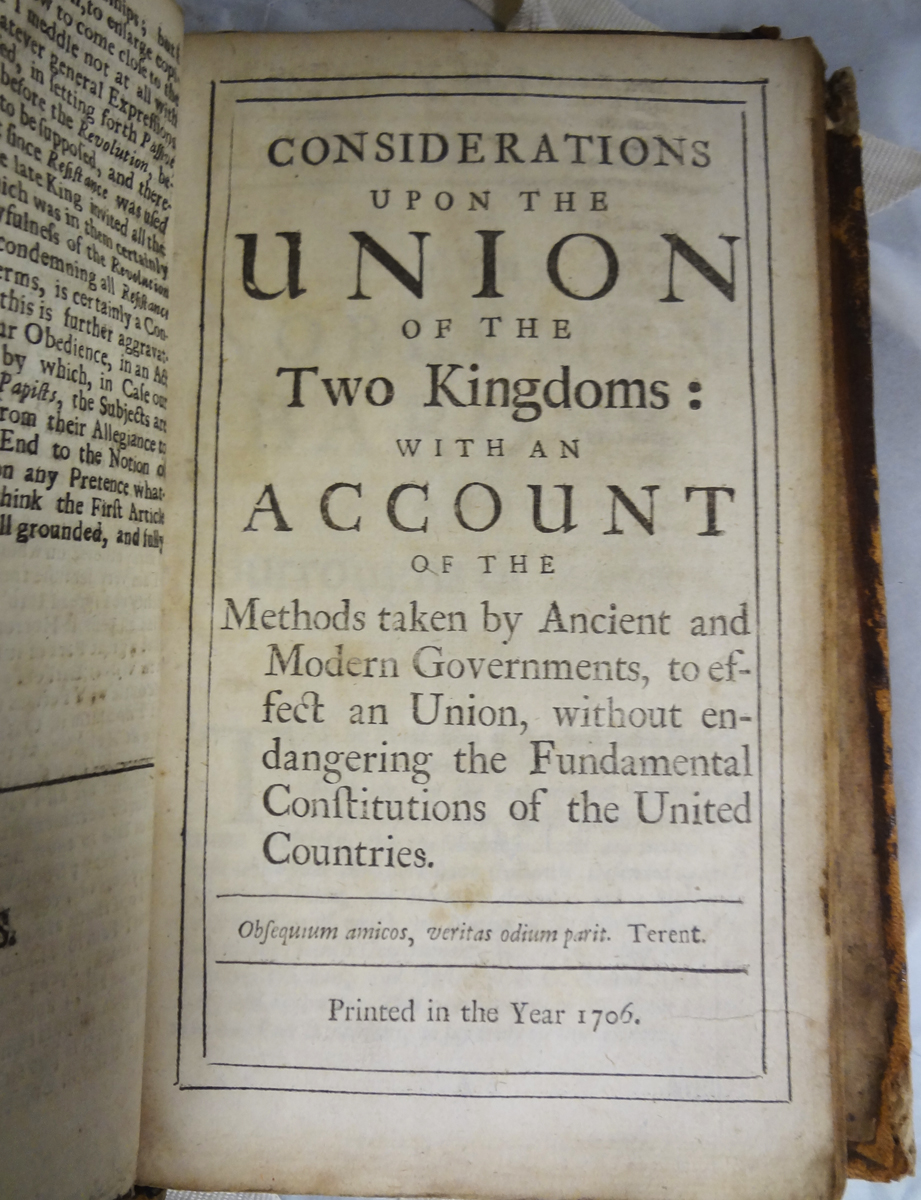

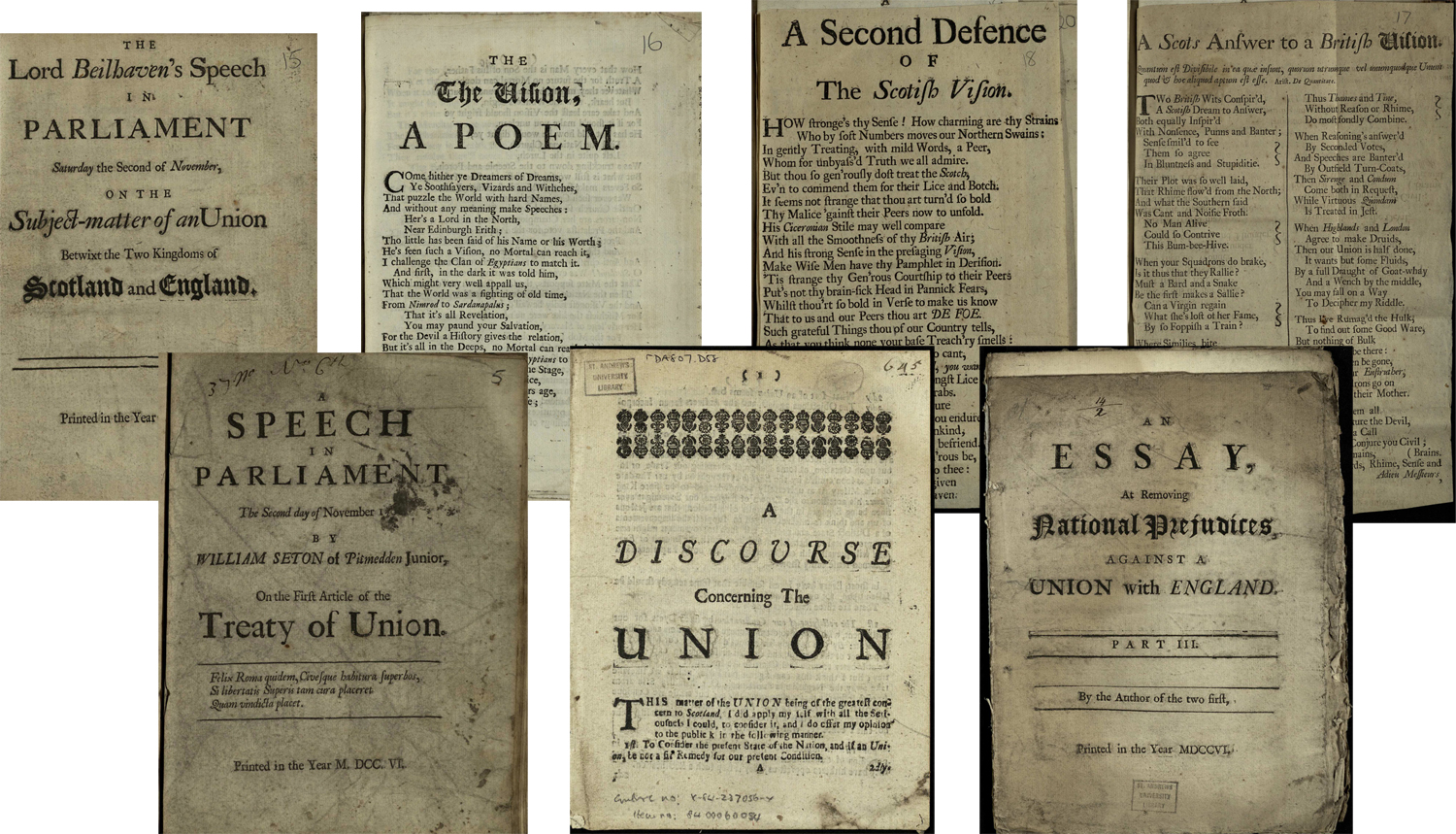

Newspapers were, of course, few and far between, and were of quite a different nature. The Edinburgh Courant for 7th – 9th October 1706 (barely a month before the sitting of the Scottish Parliament which debated the Articles of Union) was only two pages long (read the whole thing here), and its only reference to the issue was to advertise two pamphlets for sale (one of them being Ridpath’s Considerations upon the Union, noted below). Instead, the campaign literature comprises printed copies of speeches made, responses to them, and the comment and disputation of philosophers and political theorists.

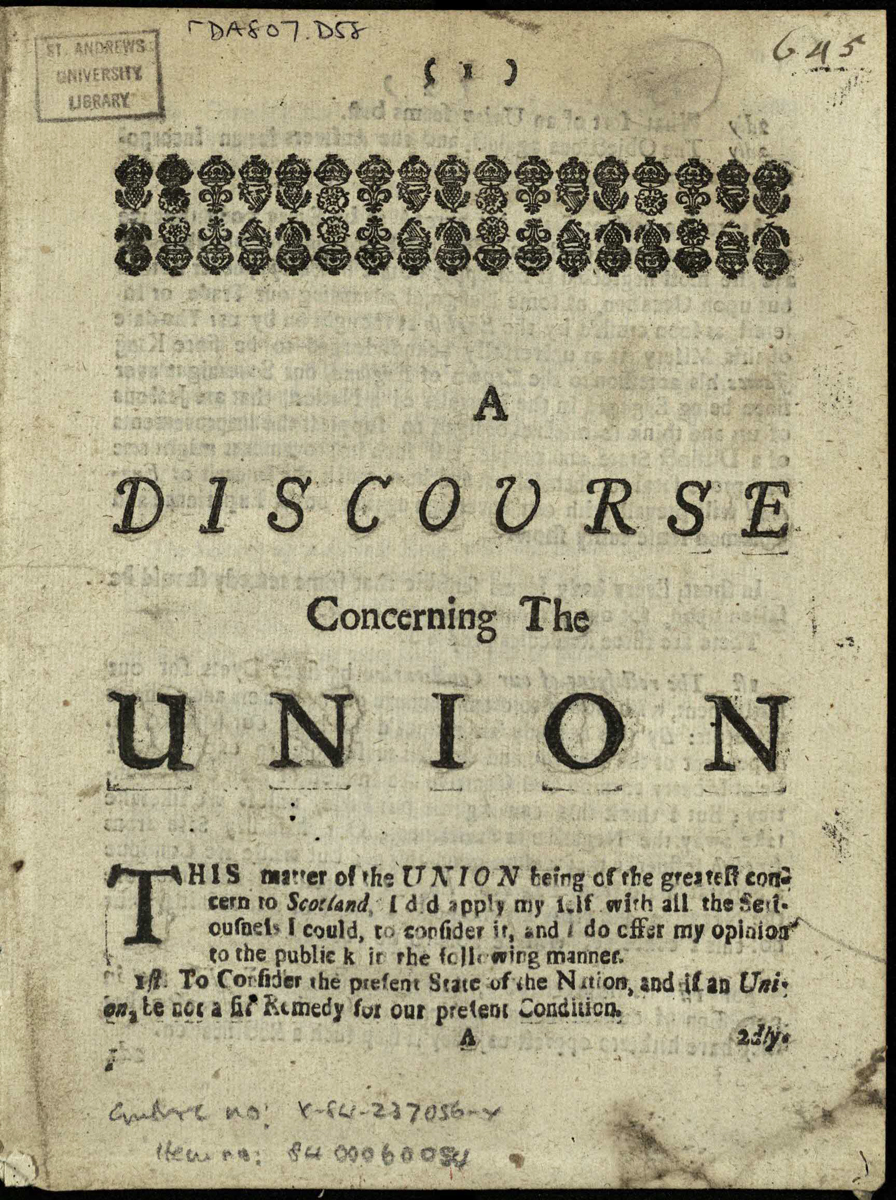

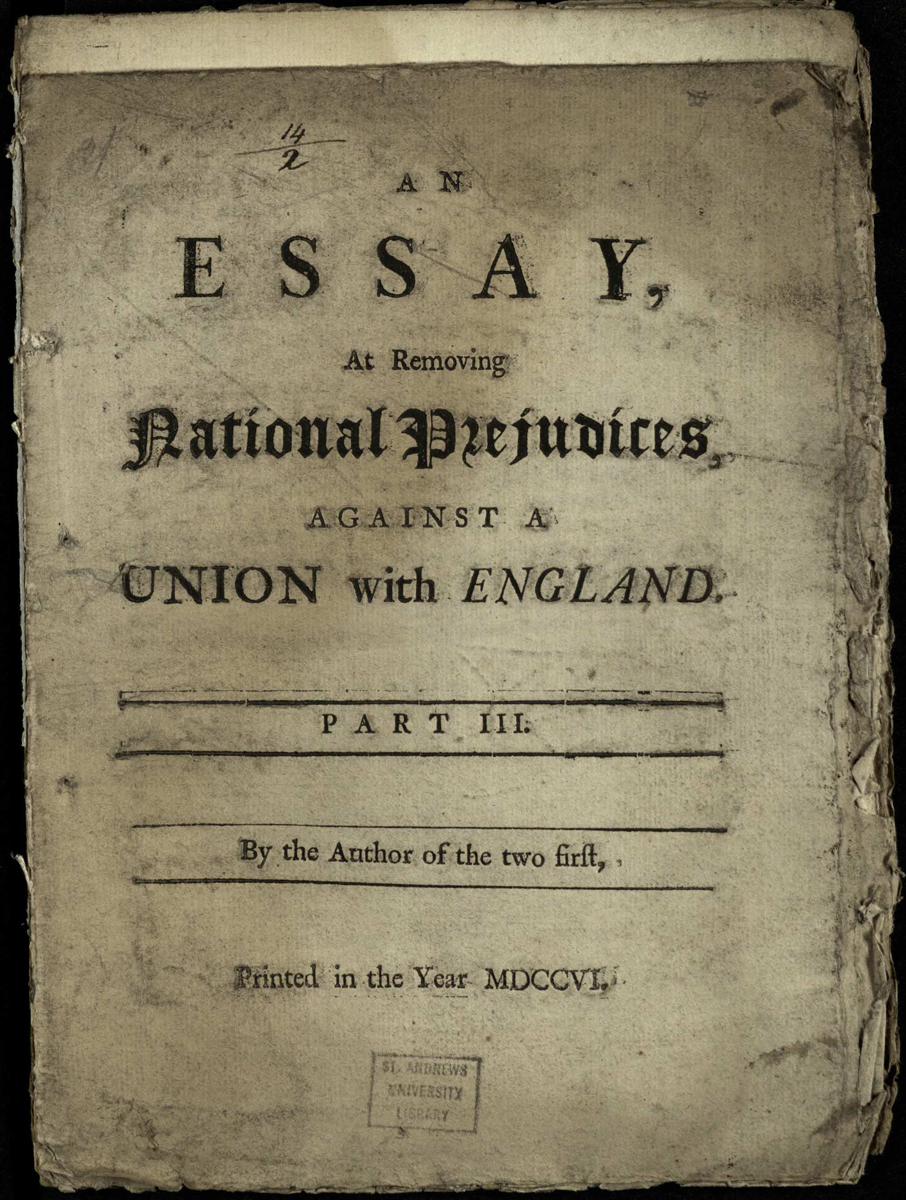

But if the people were not to be involved in the decision, their constitutional role was nonetheless debated: the famed Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun (not at all, as he is often portrayed, antipathetic to Union, but only to this particular type of Union and the way in which it was formulated) stated that “by the constitution of parliament, the Laws are to have their rise from the will and humour of the people, signified by the Lords and Commons, who (in their different capacities) are the representatives of the nation”. George Ridpath (an avid pamphleteer on many subjects) went further, stating that “it’s not only the consent of the Three Estates that is requisite, when a change in the fundamental constitution is intended, but the consent of all those whom they represent”. These ideas were ridiculed by none other than Daniel Defoe, who launched himself wholeheartedly into the debate, proclaiming that the subversive idea of parliamentary power stemming from the people was “too ridiculous” to be entertained (read his 1706 Discourse here and his 1706 Essay at removing national prejudices here); this would require “to gather the whole mob of the nation together, to judge the most intricate points of government, and how to begin or end with such a meeting, I cannot understand”. Yet, gathering ‘the whole mob of the nation together’ is just what we are presently doing.

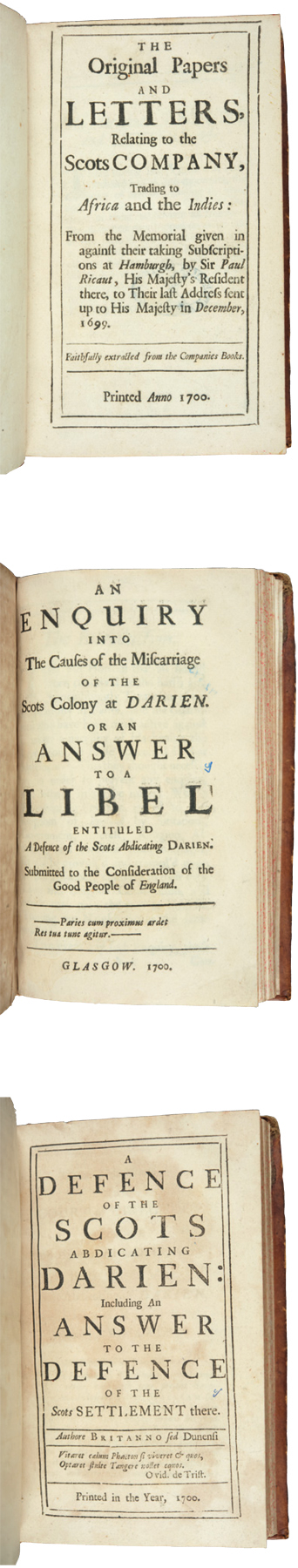

Much of the current debate, on both sides of the argument, is based on the belief that Scotland is in relative terms a wealthy and prosperous country, with significant natural resources at her disposal. This is in marked contrast to the previous discussion, when there was a complete acceptance by all that the country was in an appalling state; since the Union of the Crowns in 1603 trade had diminished and a variety of occurrences (not least the disastrous attempt to establish a Scottish trading colony at Darien) had left the country in a state of near bankruptcy. Defoe also stated that everyone agreed that Scotland was in decay, perhaps “the most neglected if not opprest state in Europe”. But herein lies another contrast with the present debate. Today, there is lively debate about the differences of political culture which might prevail between the two countries, and natural criticism of the policies (and their effects) of specific governments and parties; but in 1706 both sides of the argument openly blamed the English (the people, not just the government!) for the state of affairs which existed in Scotland. There was open admission by all – including even the English commentators – that there had been deliberate attempts to quash Scottish trade in order to limit any competition with the newly burgeoning English imperial mercantile activities. Such behaviour was seen as inevitable, and if opposed would inevitably lead to war: this was why the Union – or some other means of settling the issue – was required. “Every body seems sensible that some remedy should be fallen upon, for our present miserable state,” quoted Defoe. So in some ways there was more consensus in 1706 than there is now. The principle of closer association between the countries was barely an issue – it was the nature of the Union, and the means by which it was being effected, that were contentious.

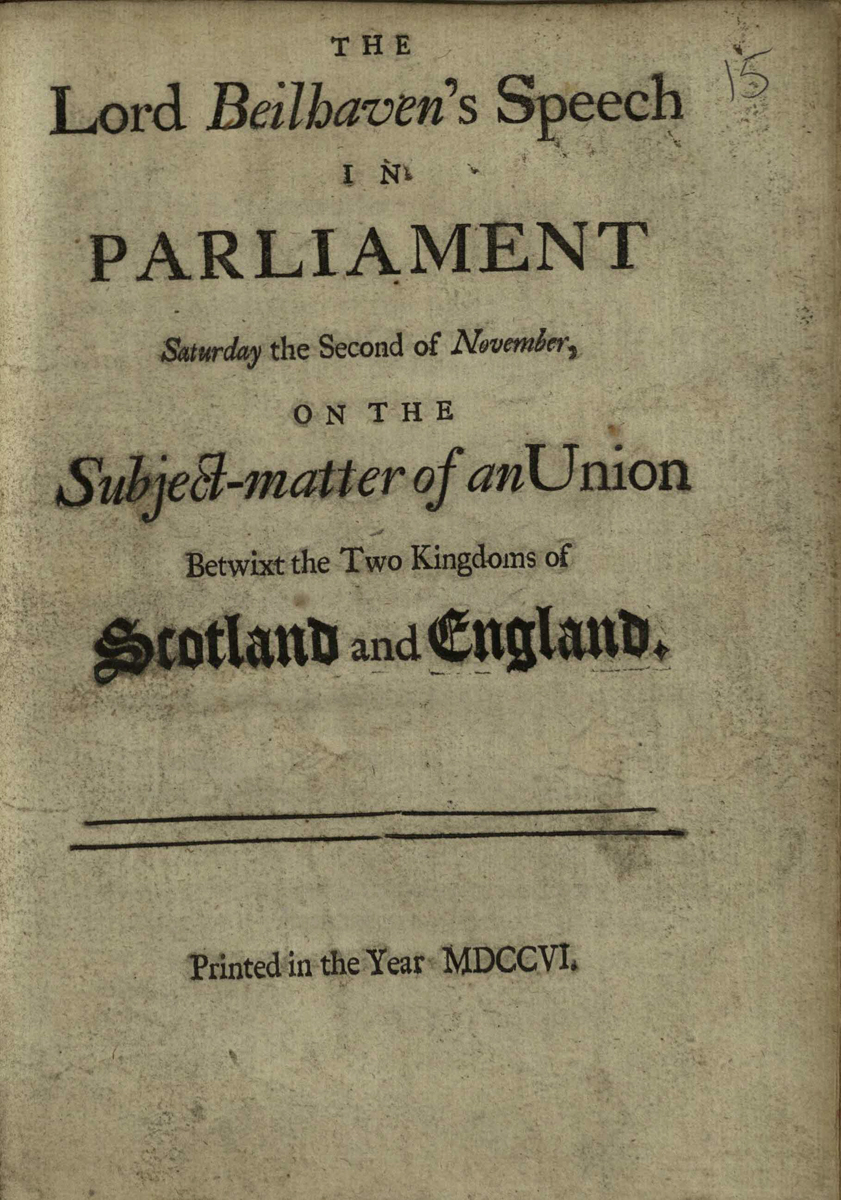

But is has to be said that some of the 300-year-old arguments sound remarkably familiar. John Hamilton, Lord Belhaven said in his speech to the Scottish Parliament, which was printed for wider circulation, that

“I find my mind crowded with variety of very melancholy thoughts…. I think, I see a free and independent kingdom delivering up that, which all the world hath been fighting for, since the days of Nimrod; yea, that for which most of all the empires, kingdoms, states, principalities and dukedoms of Europe, are at this very time engaged in the most bloody and cruel wars that ever were, to wit, a power to manage their own affairs by themselves, without the assistance and counsel of any other.”

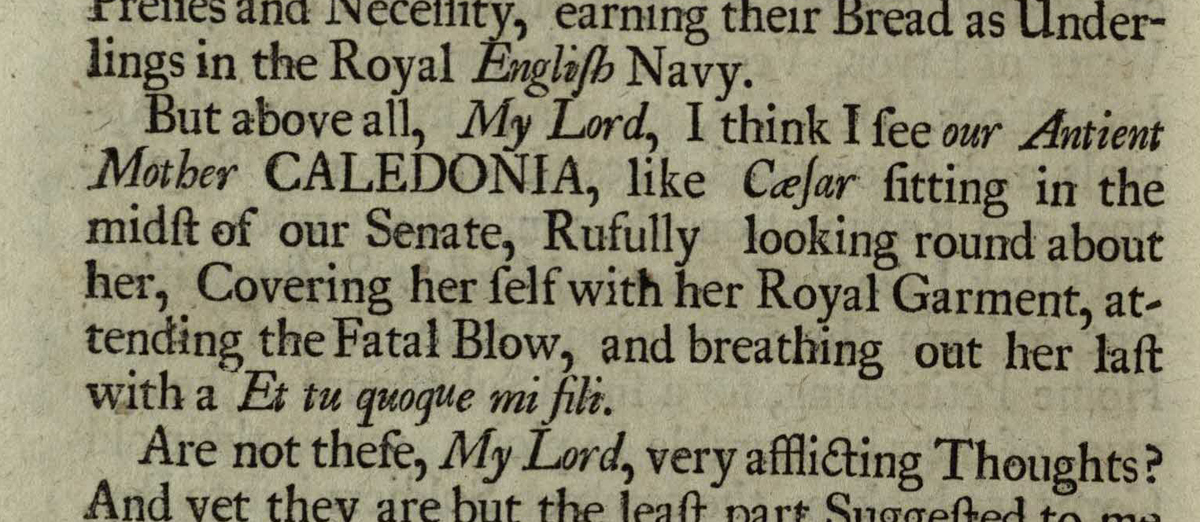

Belhaven’s approach was an overtly emotional appeal; he feared the further destruction of the nation, brought upon by the silence of Scotland’s legislators who feared to stand up against the powerful southern interests. “..above all, My Lord, I think I see our antient Mother Caledonia, like Cæsar sitting in the midst of our Senate, rufully looking round about her, covering her self with her royal garment, attending the fatal Blow, and breathing out her last with a Et tu quoque mi fili.” Today the roles are reversed: it is those advocating change who have been accused of thinking with the heart, rather than with the head (until the last, febrile days, when increasingly emotional appeal seems fair game from either side).

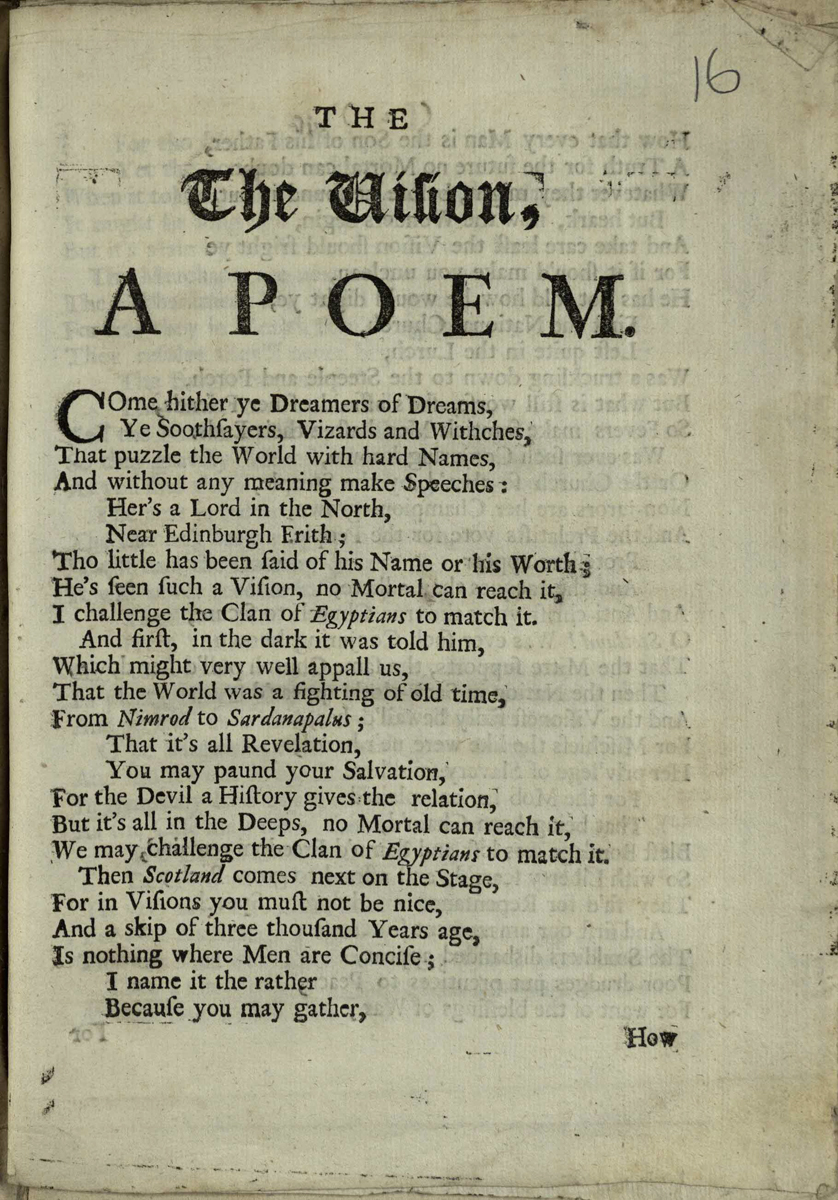

Belhaven’s approach was lampooned by Defoe in a satirical poem The Vision (read the whole thing here): each of Belhaven’s separate areas of concern were depicted in a dream-vision, in which, for example, Scottish merchants turned away from trade for fear of making too much money, and Scots were over-wrought about the fundamental question of self-determination:

“For the Mob he comlain’d

That being born Chain’d,

Blest Bondage was lost and damn’d Freedom remain’d.”

He lambasted Belhaven for hypocrisy:

“But what’s wildest of all,

And does strangely appal,

Two hours he talk’d, and said nothing at all

But let drop a few hypocritical Tears,

So the Crocodale weeps on the Carcase she tears”

And he turned Belhaven’s Caesarian metaphor against him, by stating that Brutus had acted to free his country from Caesar, who had betrayed it. He finished with a direct attack on Belhaven, and the pause which the printer inserted into the speech whilst Belhaven apparently shed a tear:

“Some said my Lord Cry’d,

Tho’ others deny’d;

Which mater of Moment it’s hard to decide,

But here’s a more difficult matter remains,

To tell if he shew’d us less Manners or Brains.”

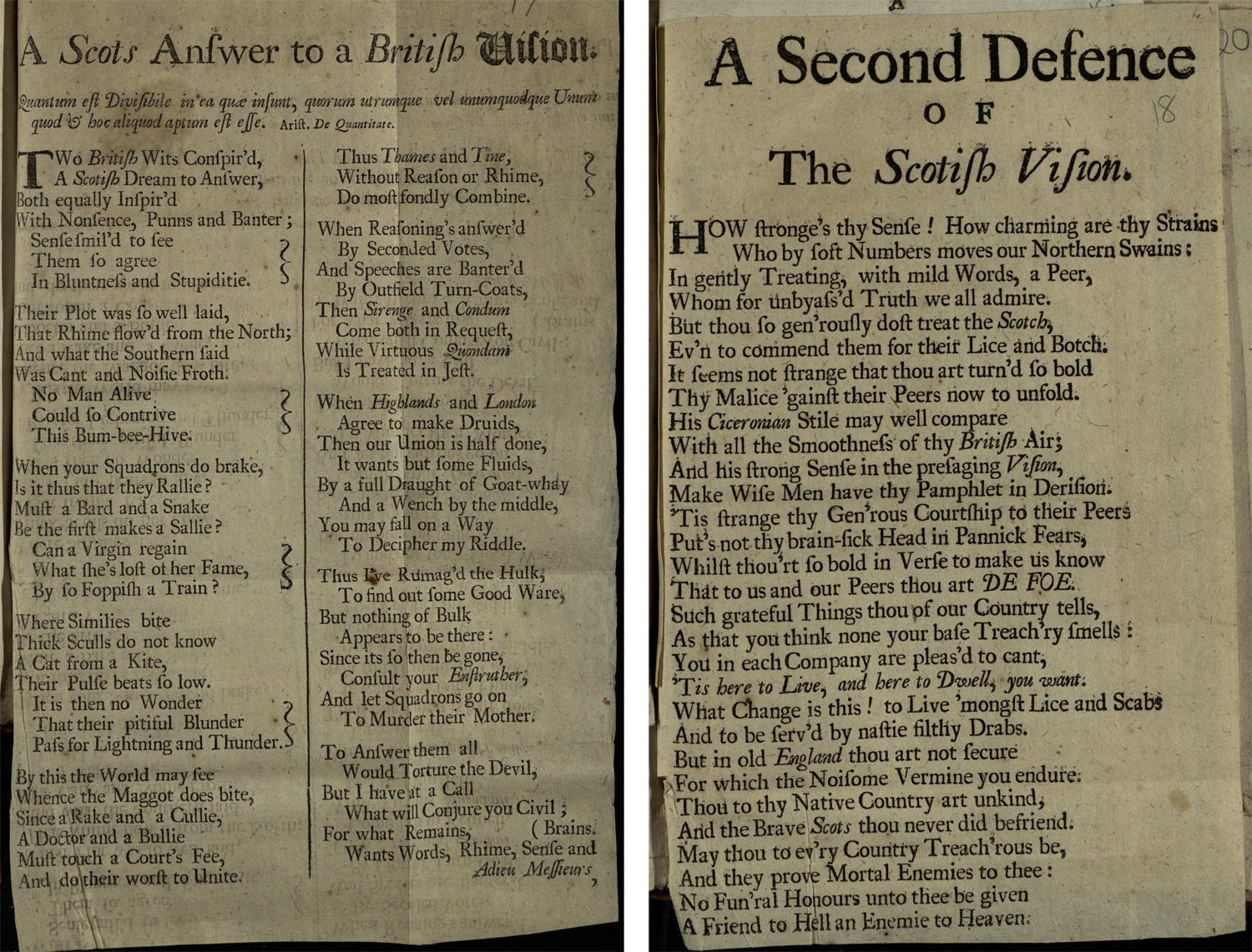

Although it was published anonymously, the author of Defoe’s Vision was readily identified, and a couple of anonymous poetical rejoinders lie cheek-by-jowl with it in the volume of pamphlets. Neither A Scots Answer to a British Vision nor A Second Defence of the Scotish Vision enter combat in terms of the political arguments, but are more simply critical of Defoe himself, on a personal basis:

“Thou to thy Native Country art unkind,

And the Brave Scots thou never did befriend.

May thou to ev’ry Counry Treach’rous be,

And they prove Mortal Enemies to thee:

No Fun’ral Hounours unto thee be given

A Friend to Hell an Enemie to heaven.”

Unperturbed, Defoe hit back. In A Reply to the Scots Answer to the British Vision he sarcastically praised the poet’s overblown language and abstruse allusions:

“What tho’ in mighty Parable was spoke,

The listning Crowd thy Oracles invoke;

Charm’s with thy Ciceronian Eloquence,

They view the Language, thou alone the Sense,

Nor is it fit th’ uncomprehending Age,

Should in abstrusest Meanings far engage.

So latine Prayers implictely thought God,

May Edifie, tho never understood.”

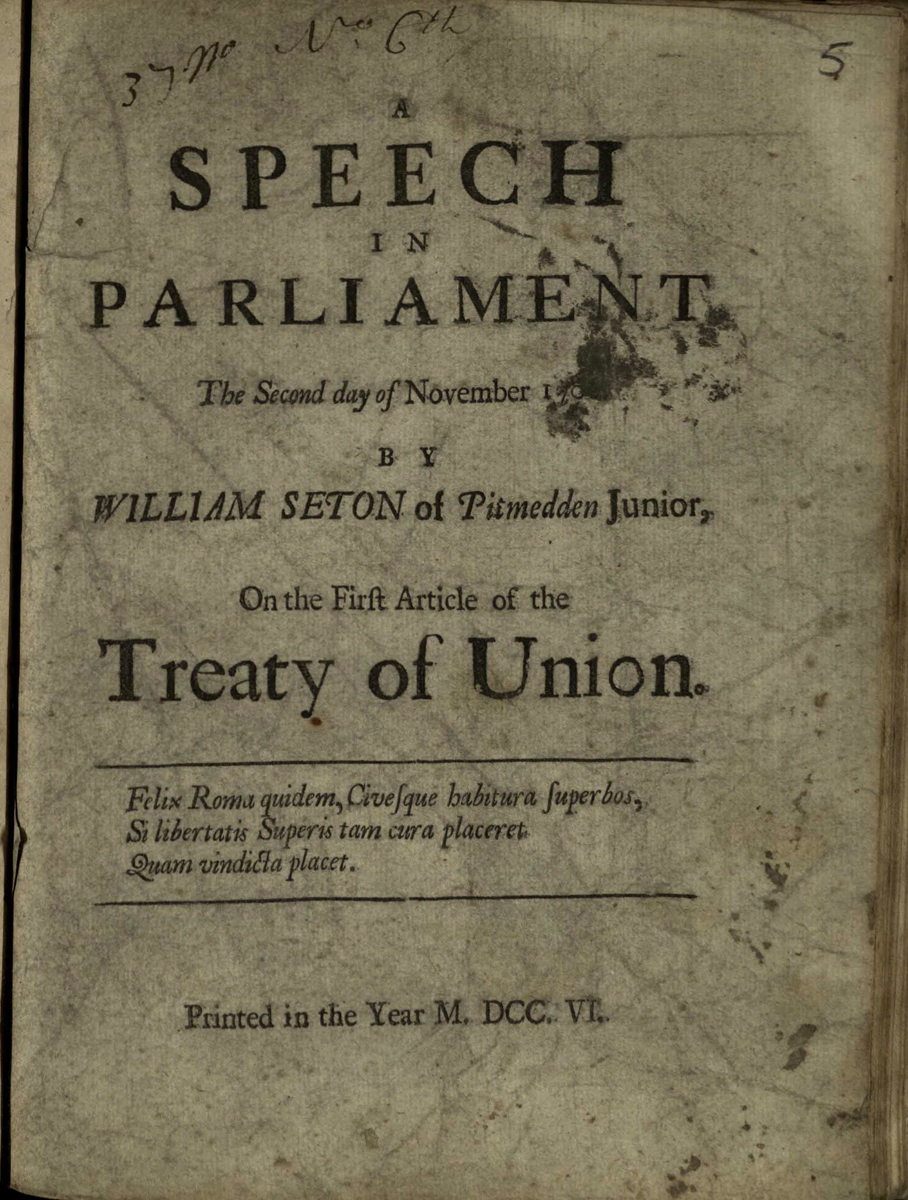

Of course, in 1706 as today, the emotional and creative case was balanced by much argument about economics, and the practical effects of change or lack of it. There was genuine concern on both sides about the languishing state of Scottish trade; but, then as now, there was no consensus about the economic out-turns. William Seton of Pitmedden, in his own speech to the Scottish parliament, was quite clear that it was through the Union that Scottish trade would thrive, and the nation would be rescued from oblivion:

“… by the Union we will have access to all the advantages in commerce the English enjoy: we’ll be capable, by a good government, to improve our national product, for the benefit of the whole island, and we’ll have our liberty, property and religion, secured under the protection of one sovereign, and one parliament of Great Britain.”

Defoe, in his essay At Removing National Prejudices against a Union with England, which can be read in full here, listed at length all the enormous material benefits the Scots would receive, and even goes so far as to say that he, and lots of other English folk, would be tempted to come to live in Scotland after the Union. (It has to be said, however, that the patronising attitude of Defoe, offering the benefits of English farmers to farm Scots’ lands for them, and other ‘improvements’ that could be introduced through English assistance, would not have endeared him to many modern Scots, on either side of the argument!)

But whether it relates to the material benefits promised by either side, or the promises made to allay fears, there is another similarity between then and now: it is clear that there was a deep-seated mistrust of the Unionist camp in Scotland by those opposing the Union. As today doubt is expressed by the ‘Yes’ camp about whether the ‘additional powers’ promised to the Scottish Parliament in the event of a ‘No’ vote will ever materialise, in 1706 there was no trust placed in the English that they would deliver the safeguards promised to protect the national church, legal system, and other constitutional issues; there was no trust that the promised trading benefits would actually accrue, and that harassment of Scottish trade would cease, rather than becoming worse as the Scots found themselves in an even weaker position. (Belhaven: “..how hard and difficult a thing it will prove, to perswade our neighbours to a self-denyal Bill.”) They believed that, in the natural order of things, the weaker part of the new nation would inevitably be done down by the stronger.

So in some ways it seems that the issue then was exactly the same as it is now. What are represented as the ‘hard facts’ of economics are regarded by many as opinion, policy, and crystal ball-gazing. Then as now, the only real argument was the clash between political cultures, and between two conflicting visions of what Scotland is and should be. Three hundred years on, the tables are turned, and it is those who favour independence who seek change. But the fundamental arguments are the same all over again.

–NR

Reblogged this on First Night History.