SPECIAL COLLECTIONS VISITING SCHOLARS – BOCCACCIO IN SCOTLAND

More than any other poet of late medieval Scotland, Gavin Douglas delighted in writing about the books he had read: the reputations of their authors, the errors he found in them, the opinions of their commentators, their great size, the lectern he placed them on, and the hailstones that fell outside as he read them.

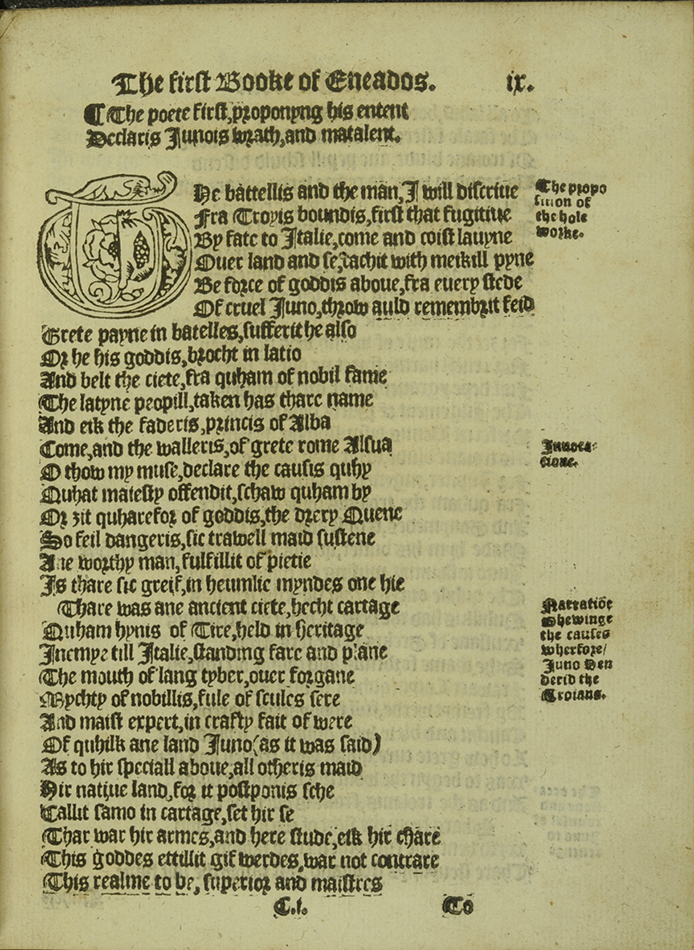

Douglas matriculated at St Andrews in 1489/90 and went on to attain his master’s degree there in 1494. He thus belonged to a generation that came of age with print culture, and could avail of the accelerated dissemination of continental scholarship. When he finished his pioneering translation of Virgil’s Aeneid into Older Scots in July 1513, Douglas set to work annotating many of the mythological details in the Roman epic. One of the volumes that was most important to him at this time was ‘Iohn Bocas in his Genealogy of Goddis’.

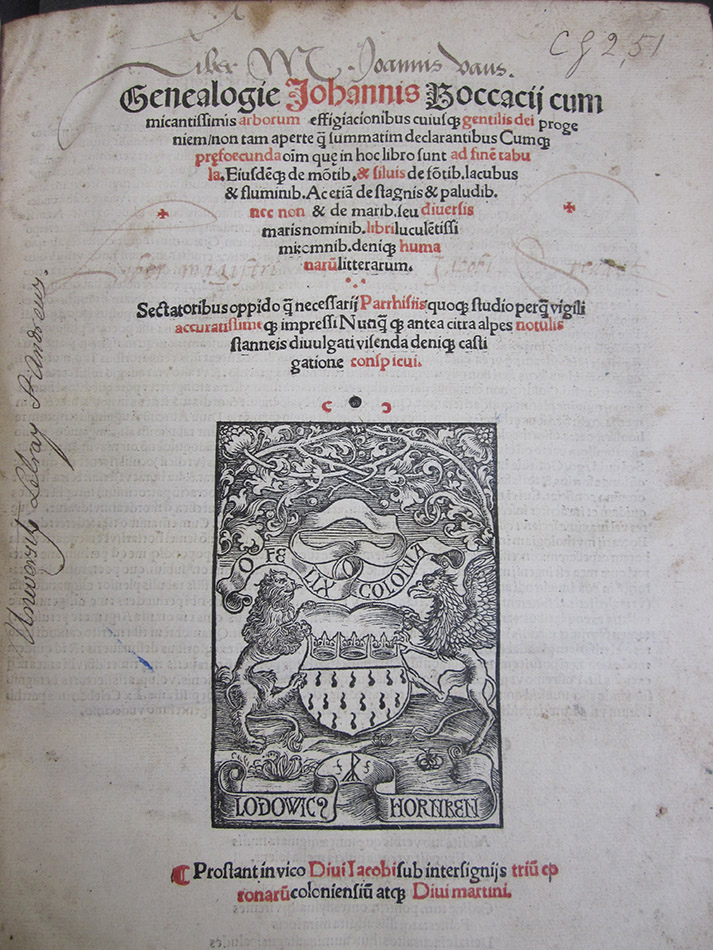

Giovanni Boccaccio worked on his enormous Genealogia Deorum Gentilium (The Genealogy of the Pagan Gods) with various intensity until his death in 1374, and for nearly two hundred years it remained the most comprehensive guide to pagan mythology available. It offered its readers an eloquent and searching account of the classical gods at a time when the details of Greco-Roman myths had become distorted or displaced by countless vernacular retellings. As he trawled through scores of sources, the Italian scholar-poet felt as though he were ‘collecting fragments along the vast shores of a huge shipwreck’, restoring what the passage of time, with its ‘silent yet adamantine teeth’, had all but destroyed.

As a feat of scholarship it was one of the formative triumphs of the humanist movement. St Andrews holds the only early edition of the Genealogia that is known to survive with a Scottish provenance. The copy was printed in Paris in 1511 and belonged to an accomplished grammarian named John Vaus, who was one of the earliest teachers at Aberdeen University. (Vaus had his own works printed in Paris in 1523.)

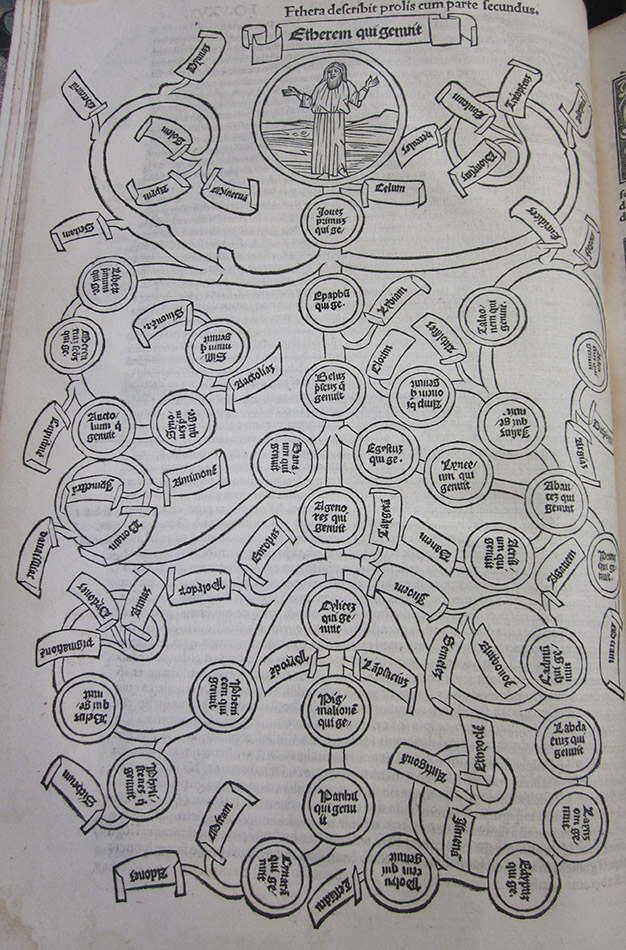

As one opens up the volume, one is most struck by the elaborate ‘family tree’ illustrations that preface each section.

Boccaccio had commissioned these illustrations for his original manuscript, and woodcut imitations of them became an attractive selling point for the print version. They served as a rough guide to the interrelations of the gods, and made each section more navigable. The 1511 edition also includes Boccaccio’s dictionary of geographical allusions in classical literature, as well as a comprehensive index for the whole book.

Such ease of reference meant that many poets could enrich their own work with the fruits of Boccaccio’s research. The Lancastrian poet John Lydgate was consulting a manuscript version as early as the 1420s. Edmund Spenser was clearly familiar with the work in the 1590s, while Ben Jonson cites it in The Alchemist in 1610. There is even evidence that Wordsworth and Coleridge were reading it together in 1803.

For Gavin Douglas, however, his familiarity with the Genealogia was a source of particular pride. When pre-emptively attacking his enemies in 1513, he writes:

Bot quha sa lawchis heirat or hedis noddis

Go reid Bochas in the Genolygy of Goddis;

Hys twa last bukis sall swage thar fantasy

[But those who laugh at this or shake their heads

Go read Boccace in the Genealogy of Gods;

His two last books will remedy their delusion]

The ‘twa last bukis’ of the Genealogia were among the freshest pieces of literary theory that the age produced. To conclude his work, Boccaccio demolishes all possible objections to his study of paganism, and in so doing, touches upon many of the most enduring questions of literary criticism. How do the circumstances of a poem’s creation affect its meaning? Should we deplore a work of art if the beliefs of the artist are reprehensible? Should poets ever explain their poems? On each page of his defence we meet a vigorous mind delighting in the vagaries of his subject. ‘Whatever the vocation of others,’ writes Boccaccio, ‘mine, as experience from my mother’s womb has shown, is clearly the study of poetry. For this, I believe, I was born.’

In September 1513, after the disastrous Scottish losses at the Battle of Flodden, Gavin Douglas put down his books. He devoted himself (with varying degrees of misery) to a life of politics, and no longer had time to puzzle over the intricacies of pagan mythology. The material remnants of pre-reformation Scotland are notoriously scant, and none of the many volumes that Douglas must have owned is known to survive. The St Andrews edition of the Genealogia bears unique witness to the circulation of a crucial humanist text in Scotland; but in its very singularity, it reminds us of how much has also been lost.

Conor Leahy

University of Cambridge

Conor spent two weeks in our Reading Room during August on our 2014 Visiting Scholars Programme. It was a delight to be able to host his visit and to see here something of the fruits of his research during his stay in St Andrews.