52 Weeks of Historical How-to’s, Week 48: How to Borrow a Library Book!

So, this week, I thought I’d take a look at how to borrow a library book – after all, this is a library blog! I’ve chosen something a little more up-to-date – a University of St Andrews Library Readers’ Guide for 1972-73, from our St Andrews Collection. This is a rather unprepossessing volume, measuring 21 cm in height, and having only 32 pages. Yet it offers a glimpse into the past of how the University Library used to operate. For those used to using the University Library today, the library as it was in 1972/73 will seem worlds away …

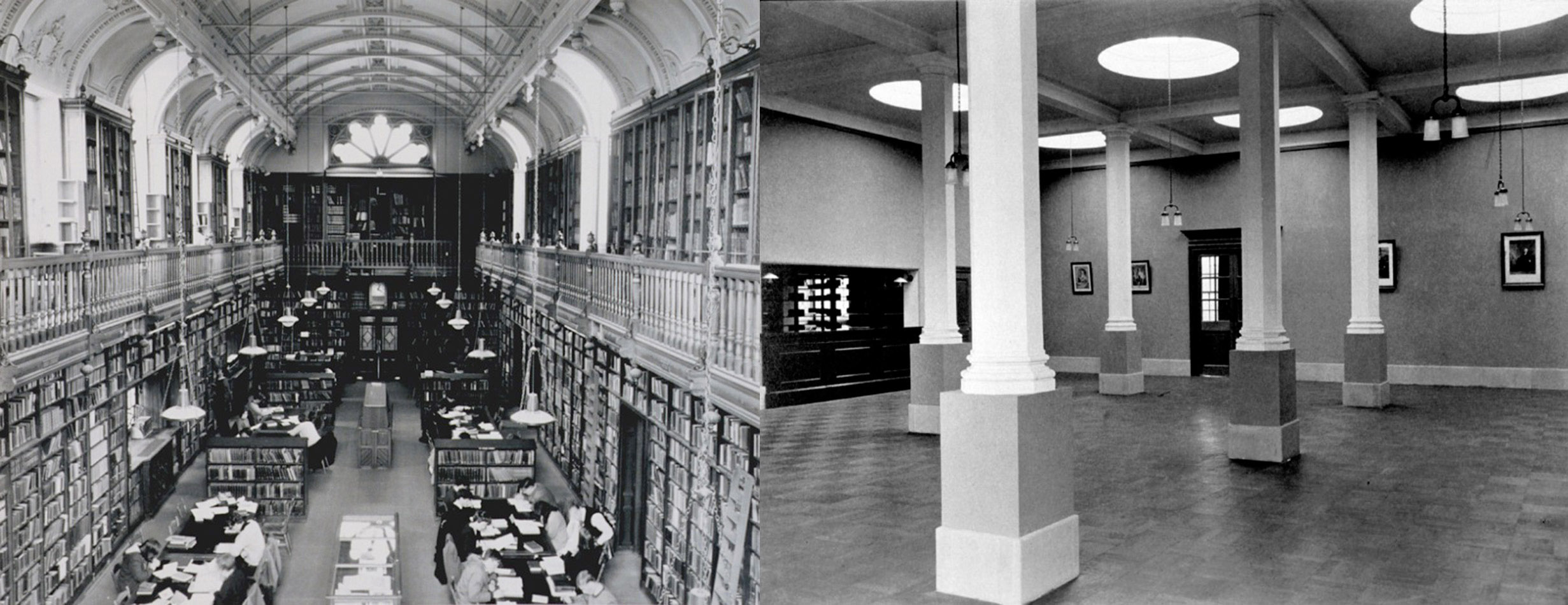

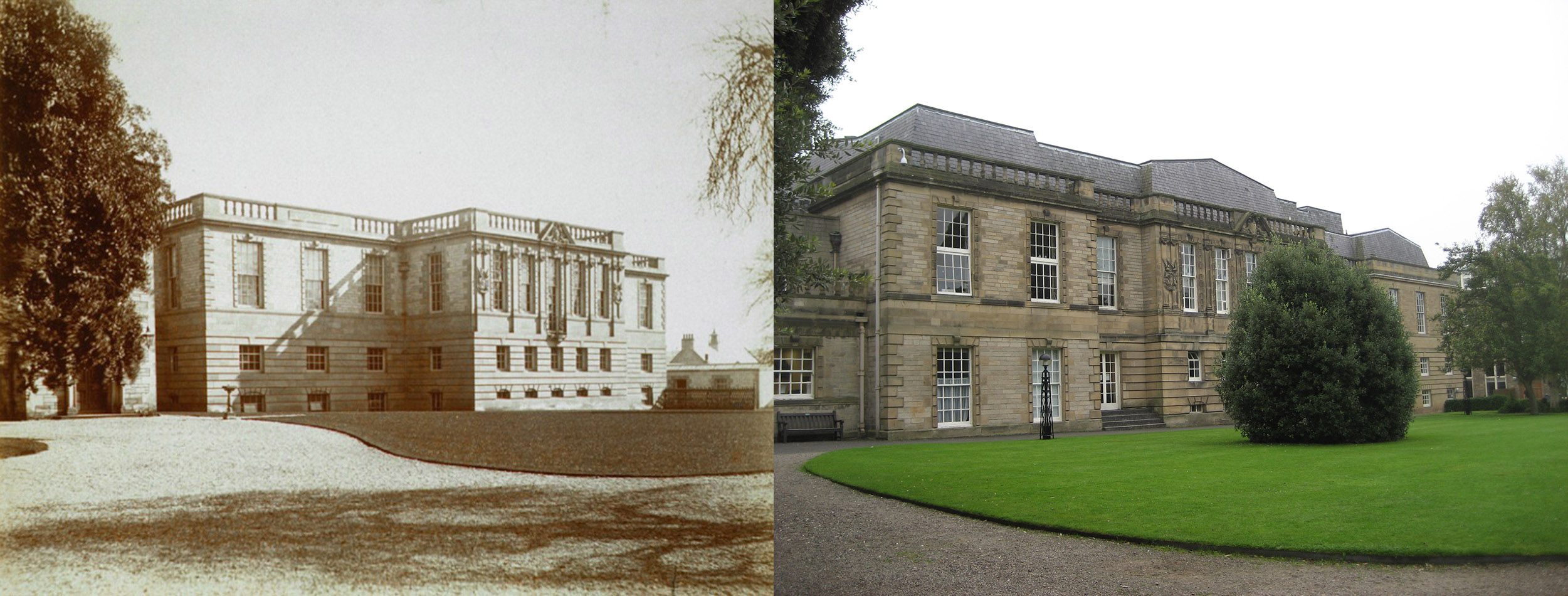

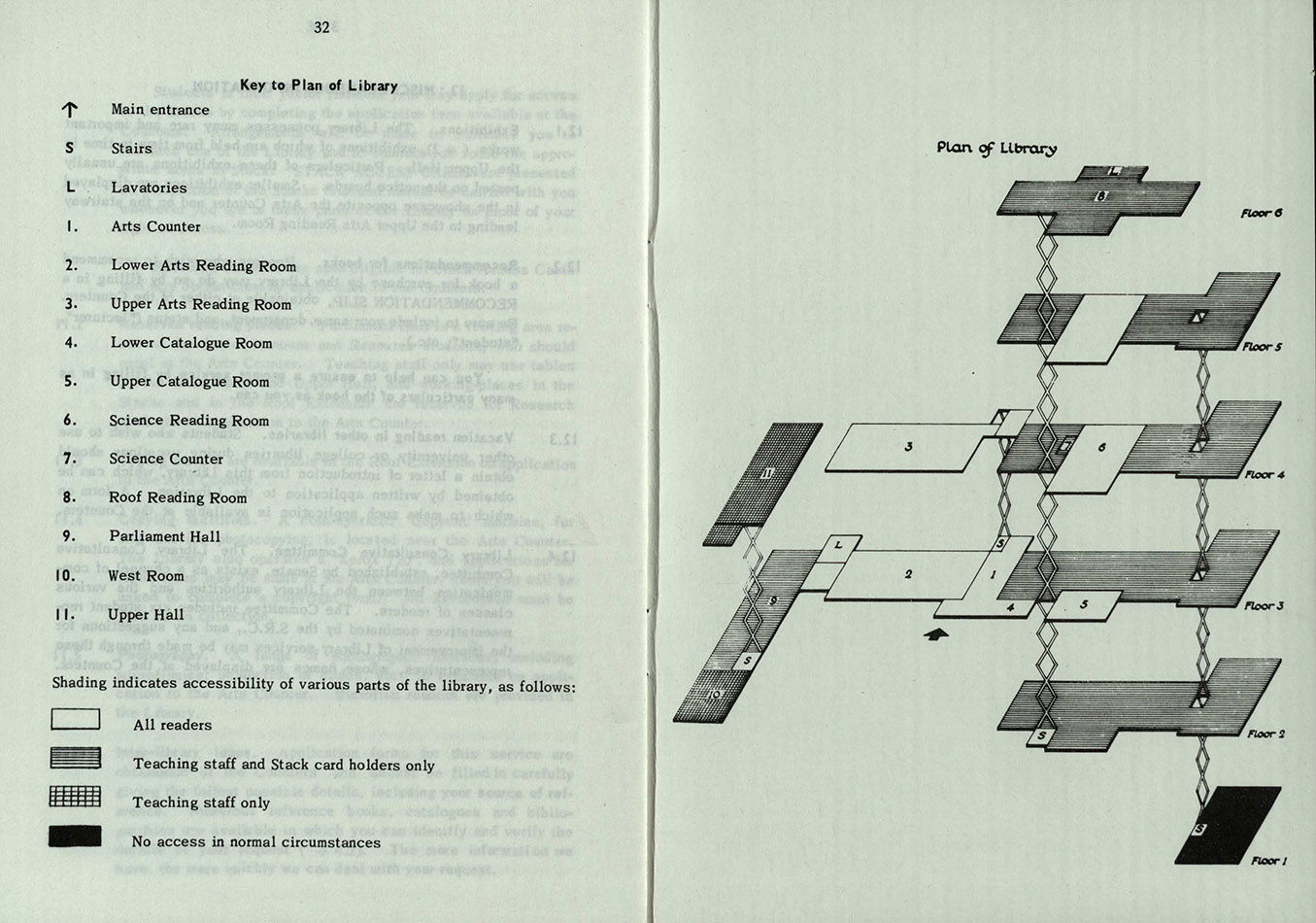

I’m sure that many of our readers will be familiar with the current Library building, with its iconic 1970s architecture. Many may also fondly remember the mustard-coloured carpets, only completely replaced at the end of the recent refurbishment in 2012. Back in 1972/73, however, our current library had yet to be built, and the Library was situated in St Mary’s Quad.

The buildings it occupied are the L-shaped complex on the left as you enter the Quad from South Street – the buildings which now consist of St Mary’s College Library (which primarily houses books for Divinity and Mediaeval History), the Senate Room, Parliament Hall with the King James Library above, and the School of Psychology and Neuroscience.

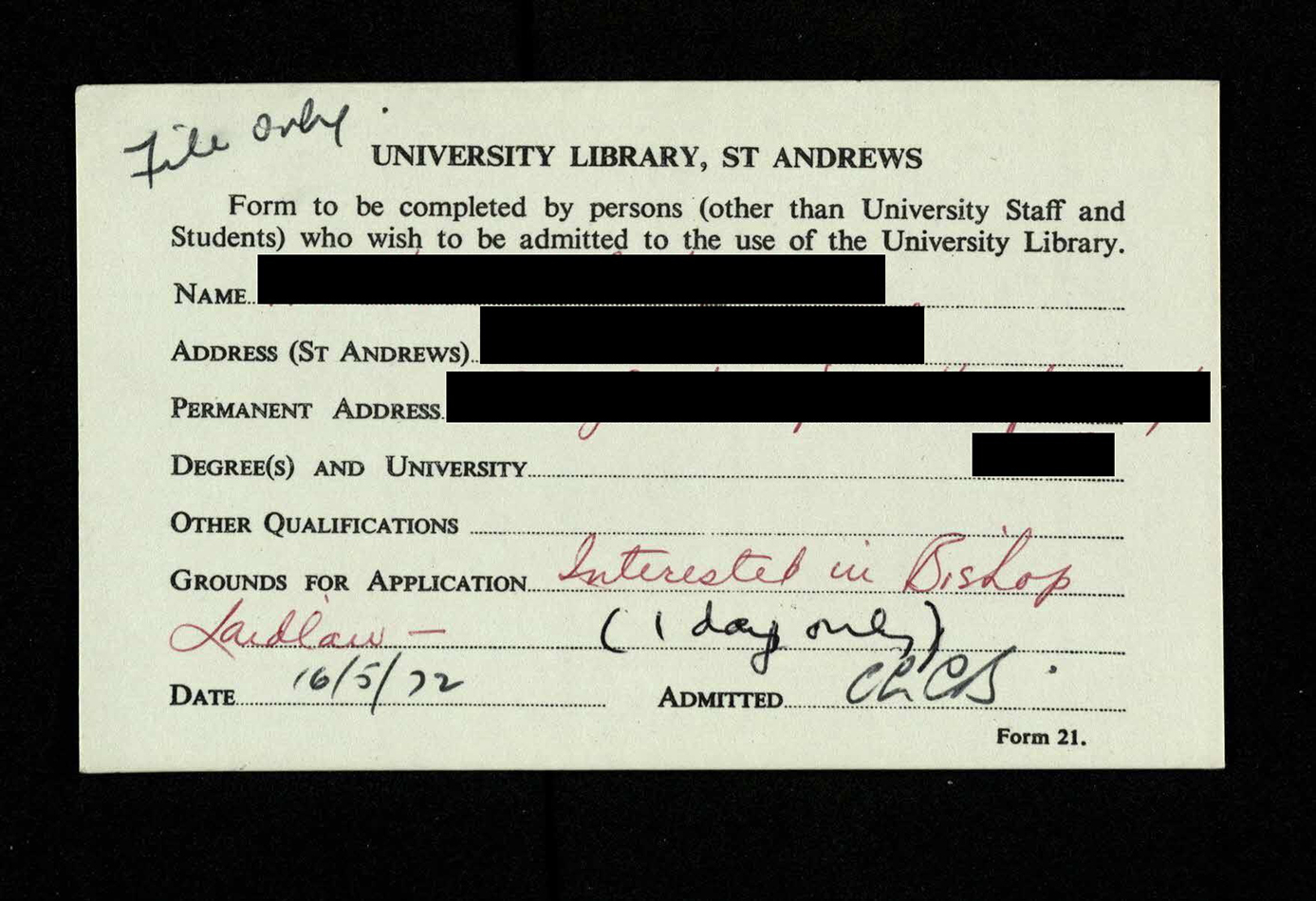

Who then, had access to the library in 1972/73? According to Section 1.6

The Library is open to members of the University Court, members of staff of the University, wives of staff, retired members of staff, graduates of this and other universities, matriculated students, and certain other persons engaged in scholarly research (on application to the Librarian).

Oh how times have changed! There is no longer the assumption that members of staff will be male (I’m not myself), and the Library is open to any member of the public, either as a fee-paying subscriber, or as a reference-only user. There is no need to apply to the Librarian (for which I’m sure he’s very thankful); all that is needed is one form of ID. In addition to the categories listed in 1972/73, the current webpage for joining the library includes staff and students from universities participating in the SCONUL Access scheme, staff and students from the University of Dundee or Abertay University, and sixth year pupils from local schools.

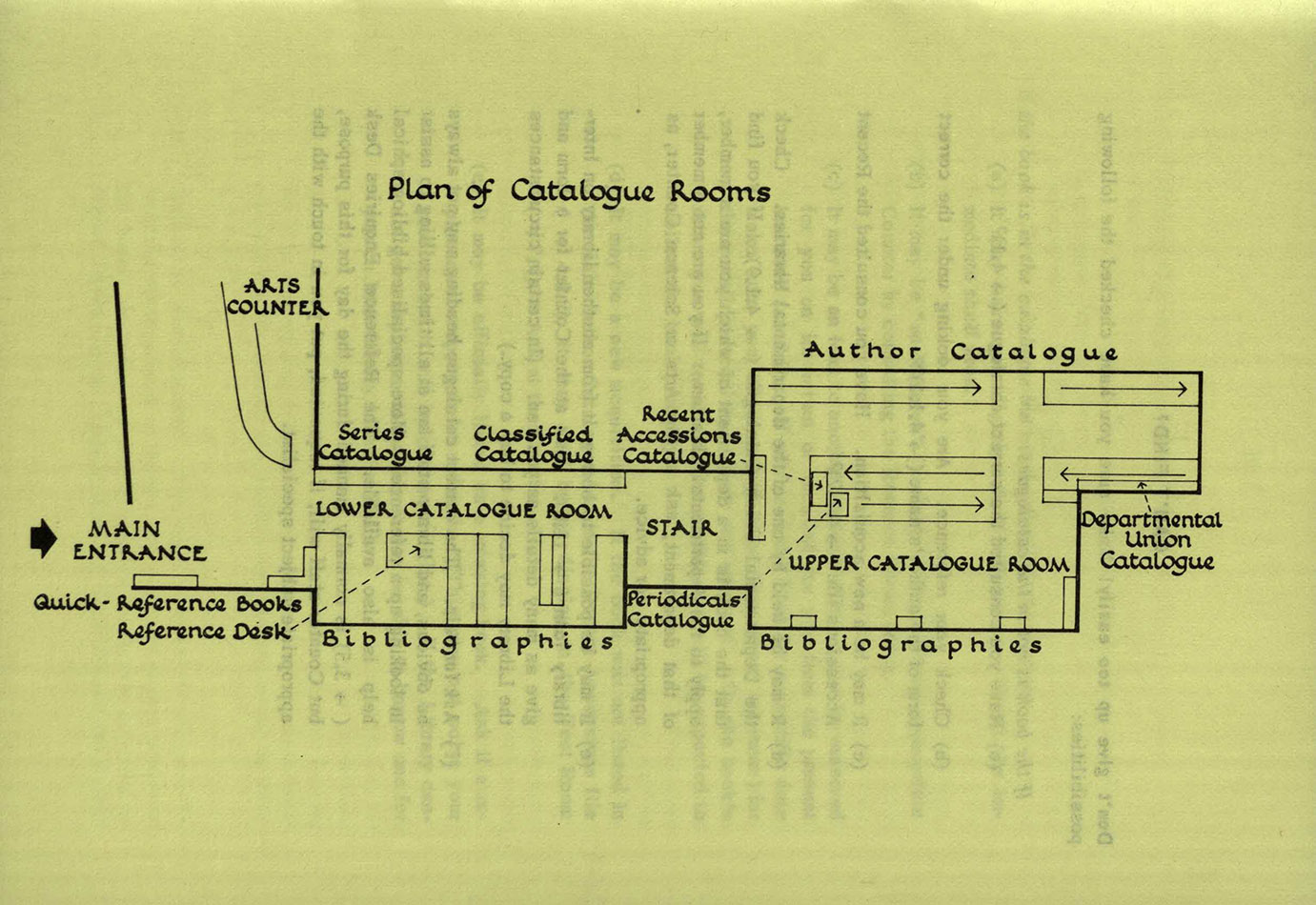

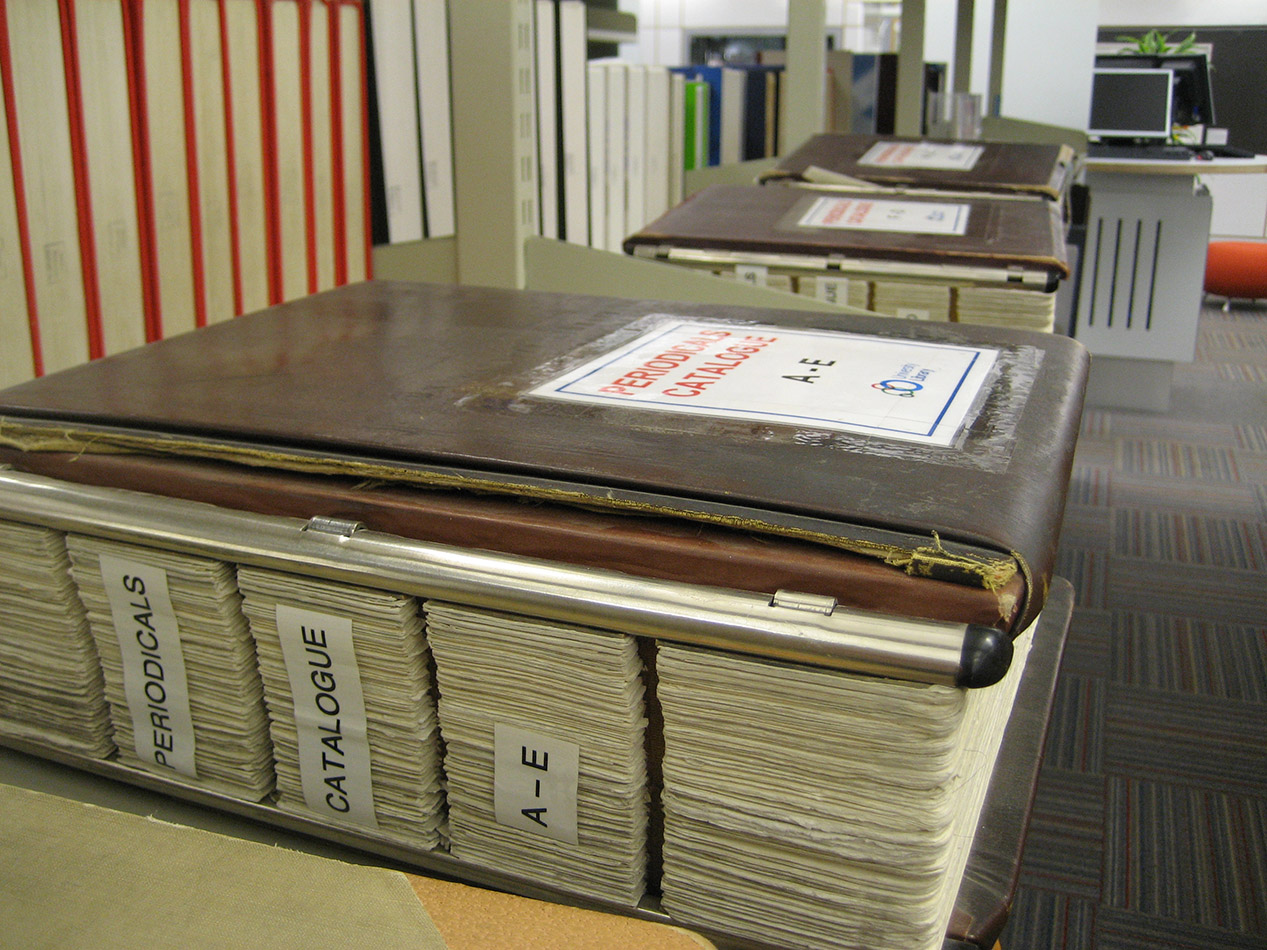

Upon gaining access to the Library, it was necessary to locate the book you wanted, both in terms of if the Library held the book, and getting its classmark in order to locate it on the shelf. To this end various Library catalogues were available, the description of which takes up five pages in the Readers’ Guide.

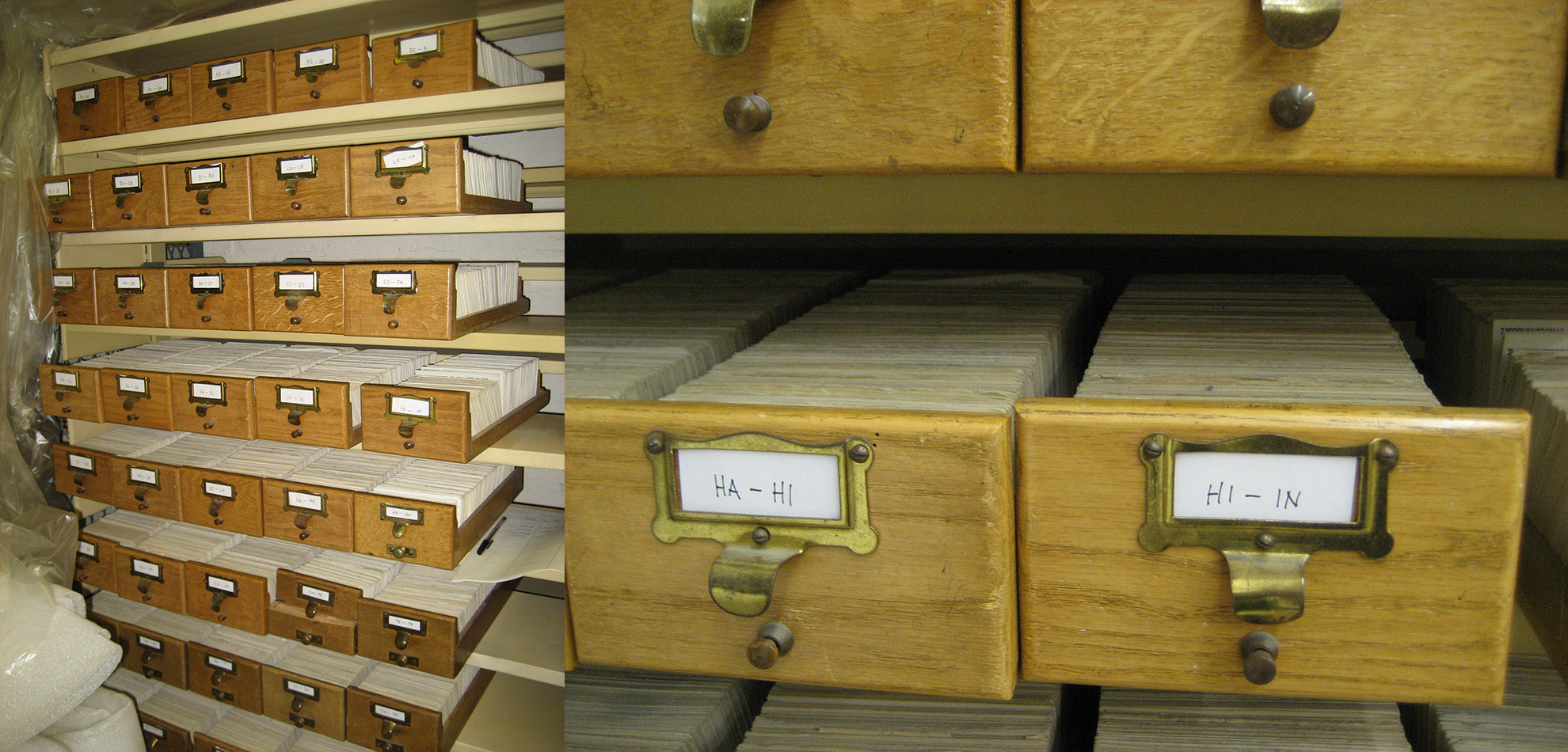

The catalogues were:

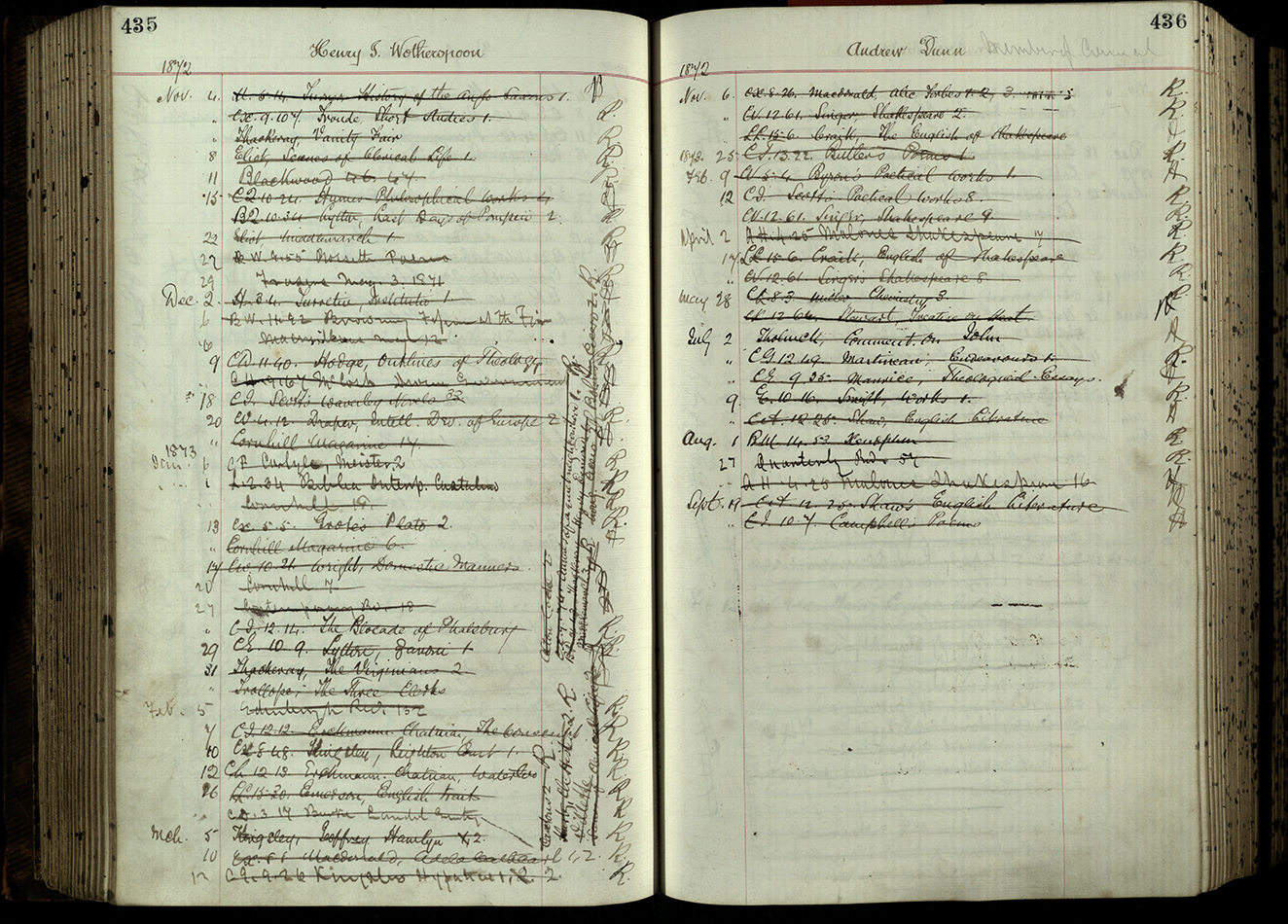

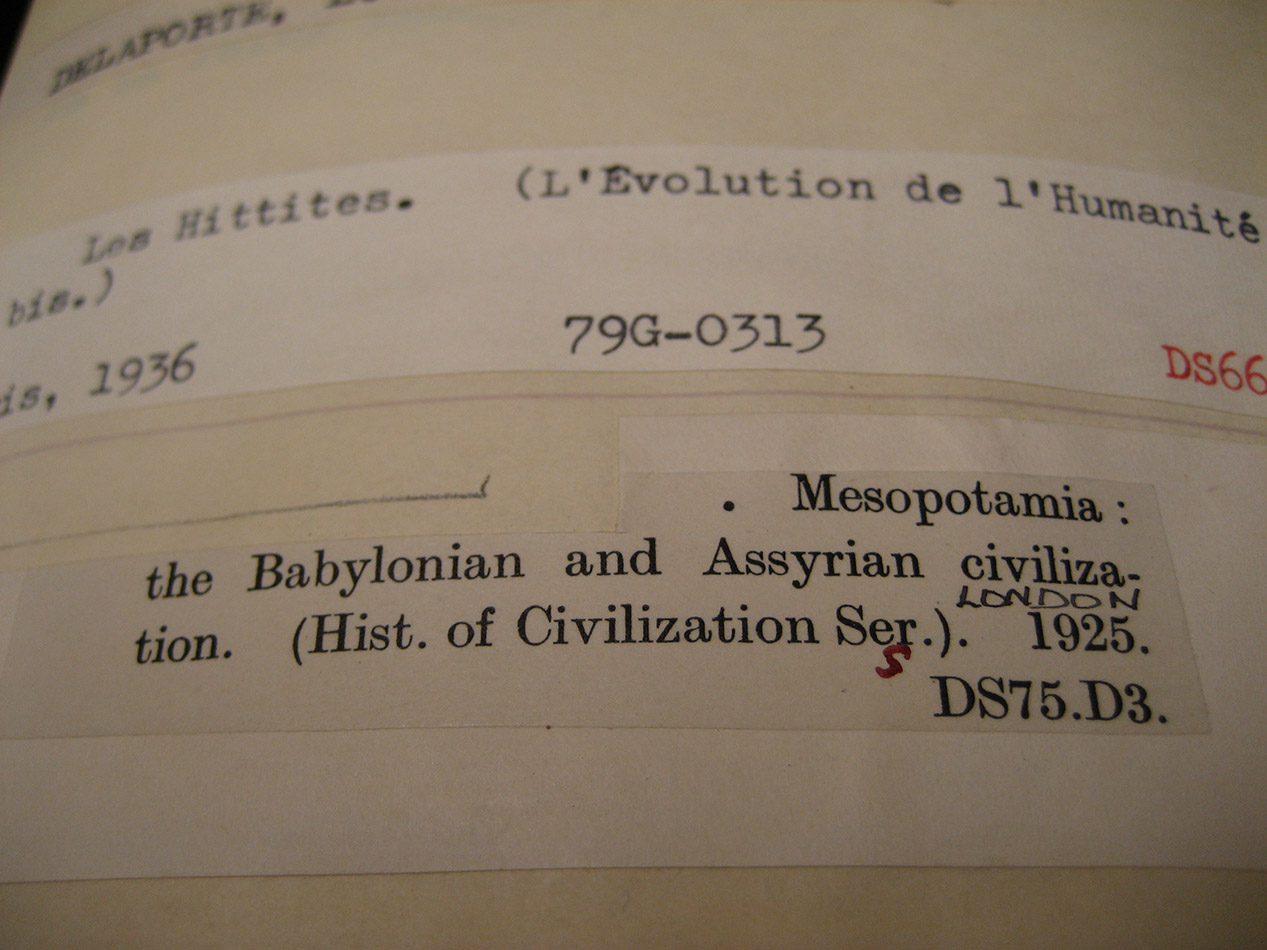

- Author Catalogue (the principal guide to the contents of the Library, known as a “page catalogue”, consisting of type-written entries pasted onto large sheets in loose-leaf binders, arranged alphabetically by author and under each author alphabetically by title)

- Recent Accessions Catalogue (a temporary drawer-catalogue of slips for books received in the Library over the previous two or three months)

- Classified Catalogue (a catalogue on cards showing the contents of the Library arranged in classmark order, i.e. by subject; as a guide, the Library of Congress’ list of Subject Headings was shelved alongside)

- Series Catalogue (giving details of the Library’s holdings in particular series or continuations, such as the Loeb Classical Library)

- Periodicals Catalogue (a single volume, recording all of the periodicals held by the Library, arranged alphabetically by first word of title, ignoring prepositions and link works such as ‘of’)

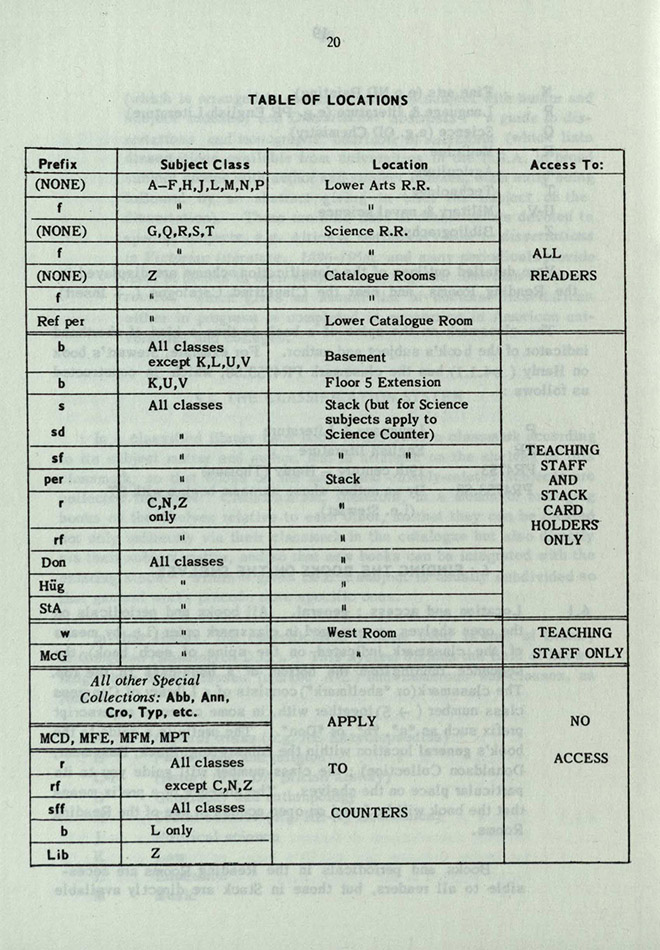

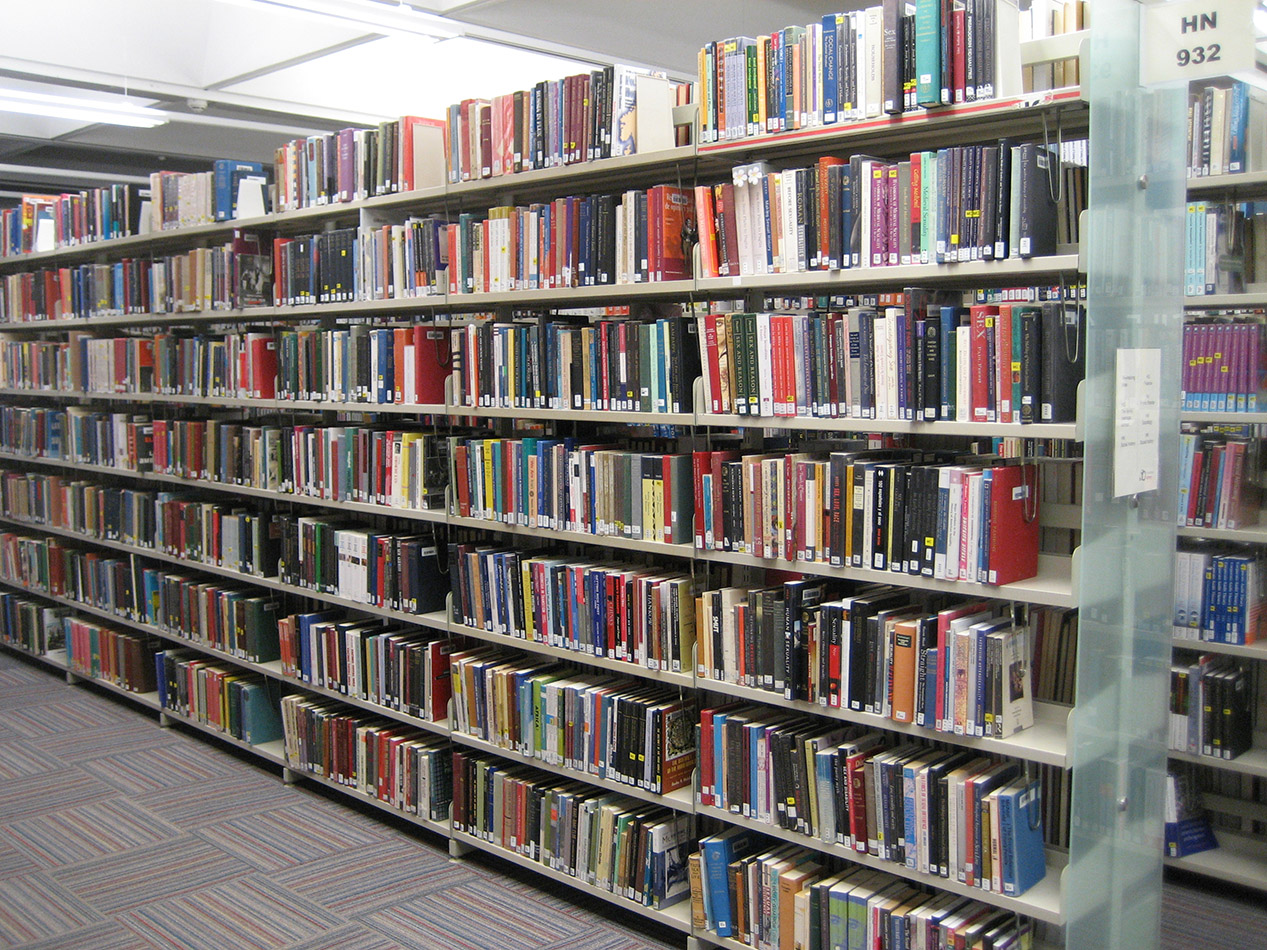

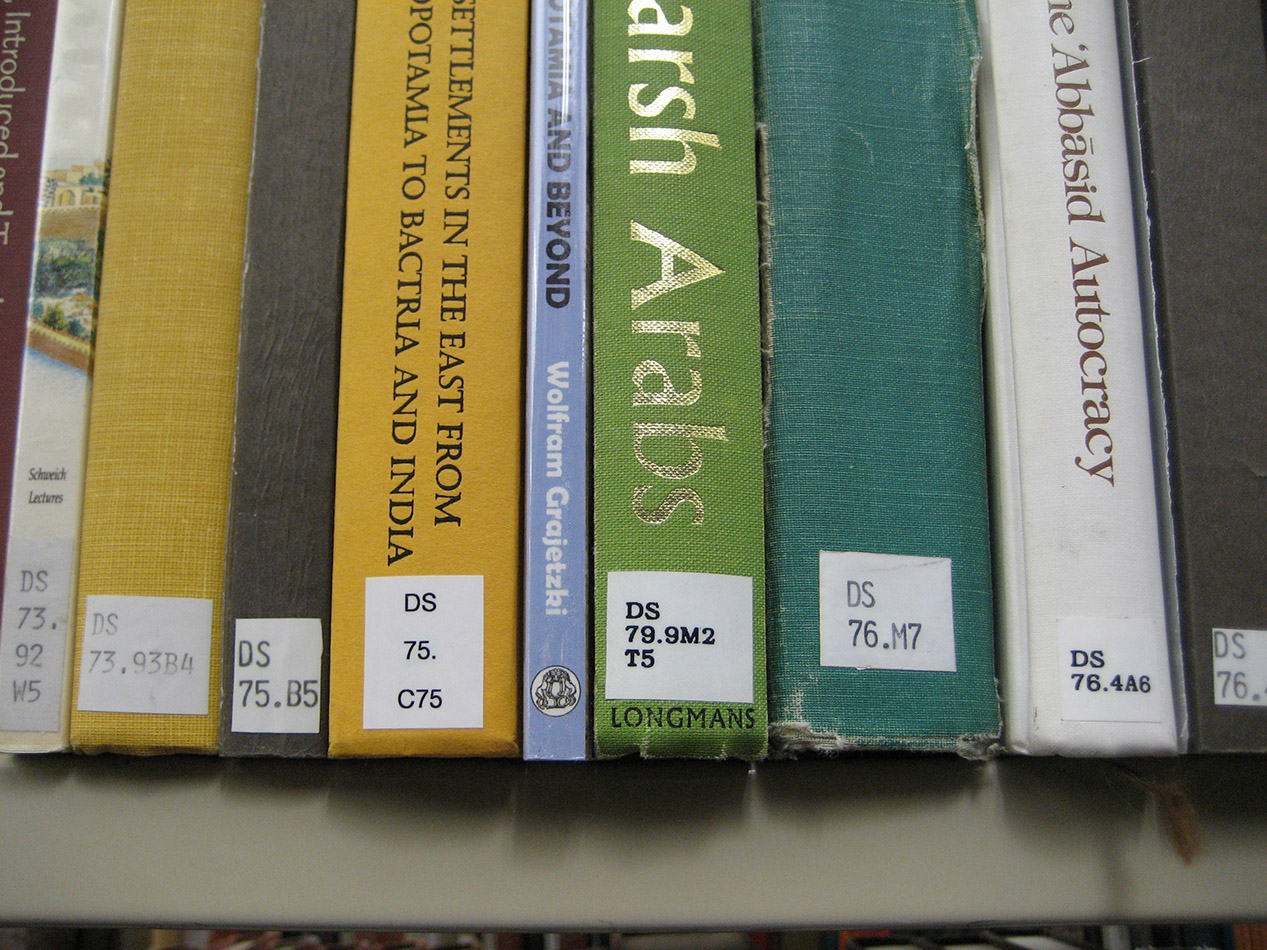

Once you had found that the library held the title you were looking for, you could locate the book on the shelves by using its classmark. As now, the Library used the Library of Congress classification scheme, which divides the field of knowledge into main classes (marked A-Z) and numerous sub-classes. For example, P stands for Language and Literature; within this PR is English Literature, whilst PS is American literature. All the books in the Library consisted of a Library of Congress class number, and in some instances a superscript prefix such as ‘s’, or ‘b’, which would give the book’s general location within the Library – in these instances, ‘Stack’ or ‘Basement’.

As today, the books had their classmark on the spine, but whereas now they are shelved top to bottom, in 1972/73 the running order was from the bottom of the book-case to the top.

The centre pages of the Reader’s Guide give handy tips for those readers who can’t find the book they’re looking for. “Don’t give up too easily!” it begins. The first tips are those for a book not in the catalogue (such as consulting the correct catalogue, or looking under the correct form of the author’s name), whilst the second set of tips is for when a book is listed in a catalogue, but is not in its place on the shelf. In this instance readers are advised to do such things as check the immediate shelf area (as it may have been shelved out of sequence), or to check the Reserve Books index in case it is on reserve. Should the book be officially listed as missing, readers could ask for a replacement copy to be ordered; “This may not solve your problem but it will help someone else”.

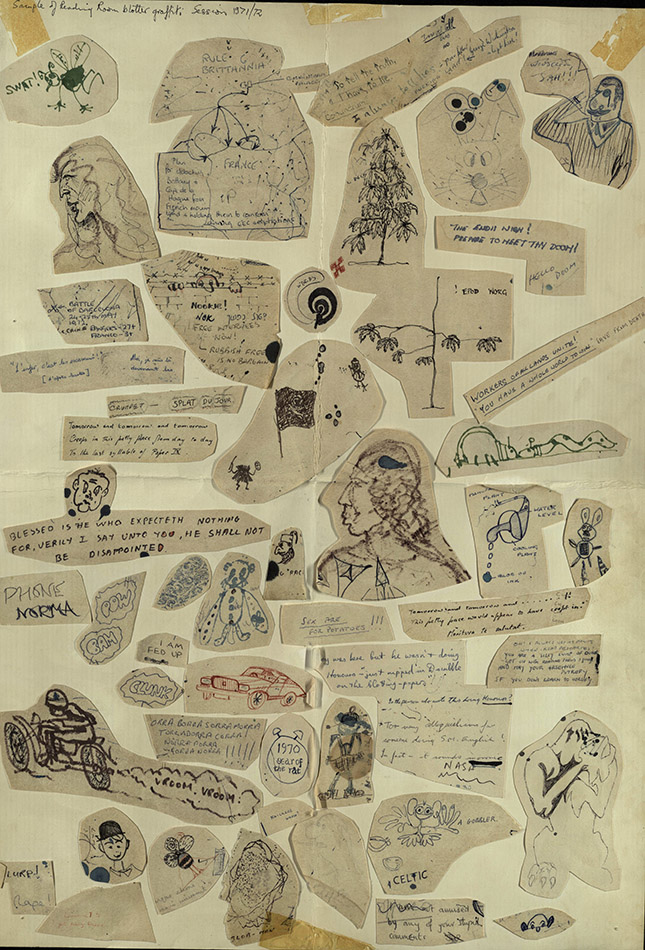

Not all books were on the open shelves. All readers had access to the Lower Arts Reading Room and Science Reading Room (both of which housed the books most constantly in use in their respective subject areas), and the Catalogue Rooms and Lower Catalogue Room. The Basement and Stacks were restricted to teaching staff and stack card holders, whilst the West Room and Upper Hall (now the King James Library) were restricted to teaching staff only.

As today, space was an issue: “For reasons of space it has been necessary to make some temporary transfers of books and periodicals to certain of the teaching departments, and to the Library Store at the North Haugh”. Even 40 years ago there was a Store at the North Haugh! (although not the current building, which houses Special Collections; in 1972/73 the store, known as ‘The Tunnel’, was located in the space beneath the high-level entrance to the Purdie Building.) These books were not inaccessible, but could be retrieved via application to the department, or to one of the Library Counters.

Apart from the exceptions set out in Section 7 (which included books on reserve, special collections, new books, and reference only books), all books and periodicals on the open shelves could be borrowed for home reading. But there were rules to be followed.

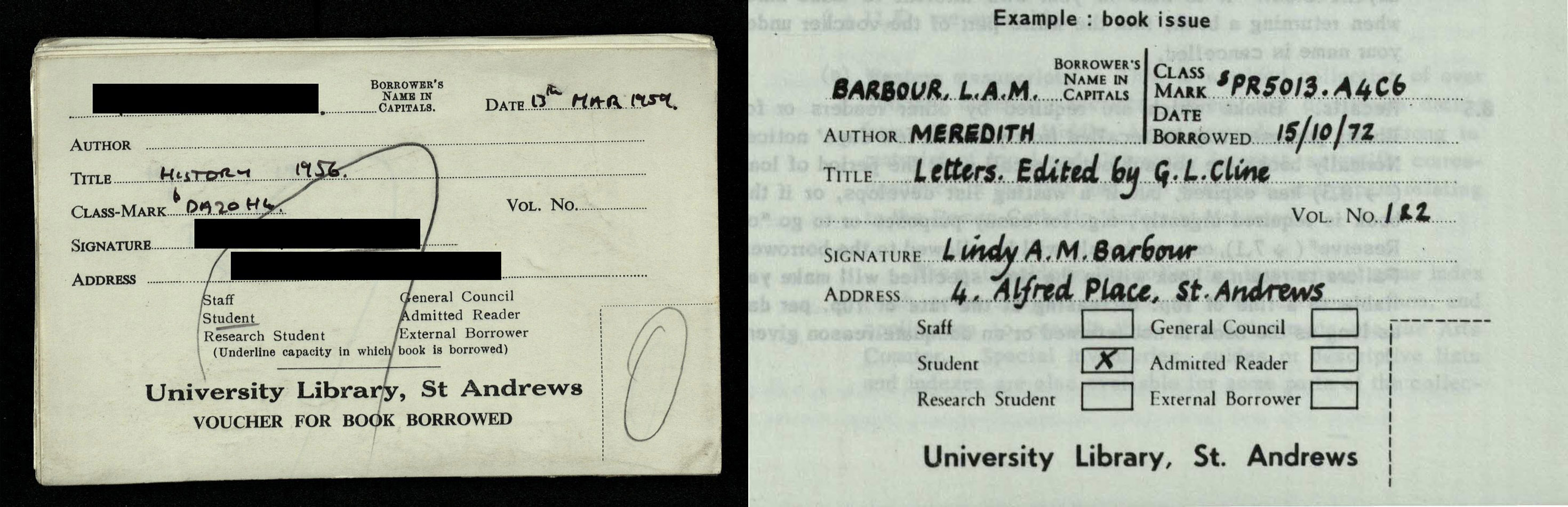

Before borrowing a book a reader had to register by completing a Reader’s Card at the appropriate Counter (either the Arts Counter or the Science Counter). There were a set number of books which readers in any given category could borrow – Honours students (those in their 3rd or 4th year) could borrow 10 volumes at a time, all other undergraduates only 6. Loan periods also varied. Matriculated students could borrow a book for 14 days, all other readers for 4 weeks, although “books may usually be retained until the end of term provided they are not required by other readers or for other library purposes.”

Before a book could be taken out of the library a Borrowing Voucher had to be completed: “Until this is done the book must not be removed from the Library under any circumstances.” This consisted of two parts, a white and yellow part. The white part was filed under the reader’s name, whilst the yellow part was filed under the book’s classmark (which enabled the book to be recalled if required by another reader). It was the reader’s responsibility to ensure that the white part of the voucher was cancelled upon returning the book.

To start with, I could go to the library during the 1972/73 opening hours; it’s term time now, so that would be 9am-10pm Monday to Friday, and 9am-12.15pm Saturday. This fits in with the current opening times, so no problems there. Next, I can look for my book in the page catalogue, as we still have these in the library. The item I’m after is L. Delaporte’s Mesopotamia: the Babylonian and Assyrian civilization (London, 1925), which I manage to find in the Page Catalogue, no. 114 (Decker, M – Delbasc). This tells me it has the prefix ‘s’ and the classmark DS75.D3.

In the 1972/73 library this item would have been in the stacks, accessible only to teaching staff and stack card holders (Junior Honours students and Research students could apply for these cards), although presumably as a member of Library staff I too would have had access. So I have no excuse, and must find my own book – which, being a monograph, should be on level 3 of the current Library.

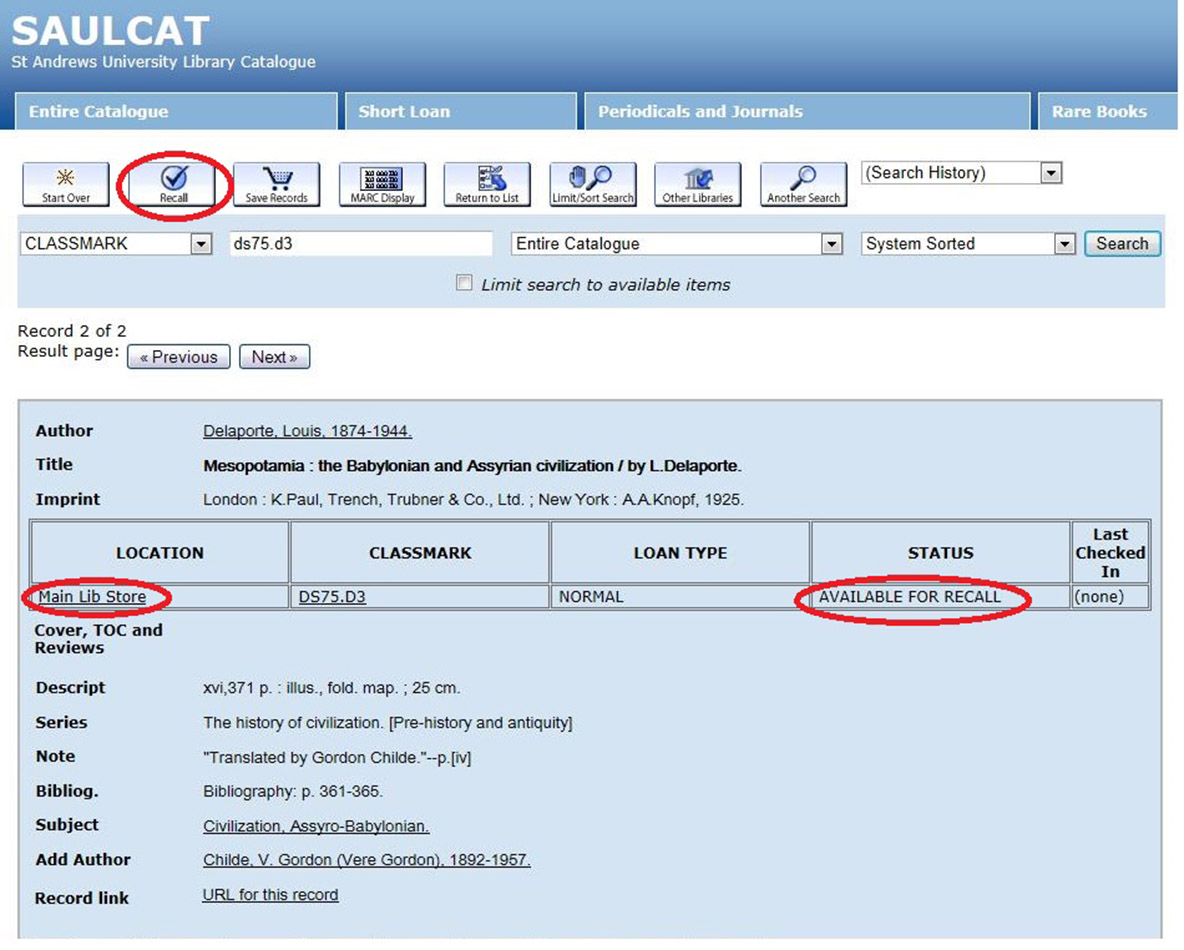

But to my frustration, the book isn’t on the shelf. Following the advice in the Reader’s Guide I don’t give up too easily, and check the immediate shelf area, but with no luck. So it doesn’t look as though it has been shelved out of sequence. Well, this is 2014, not 1973, so I decide that I should use the other finding aids at my disposal, and check the online catalogue, SAULCAT.

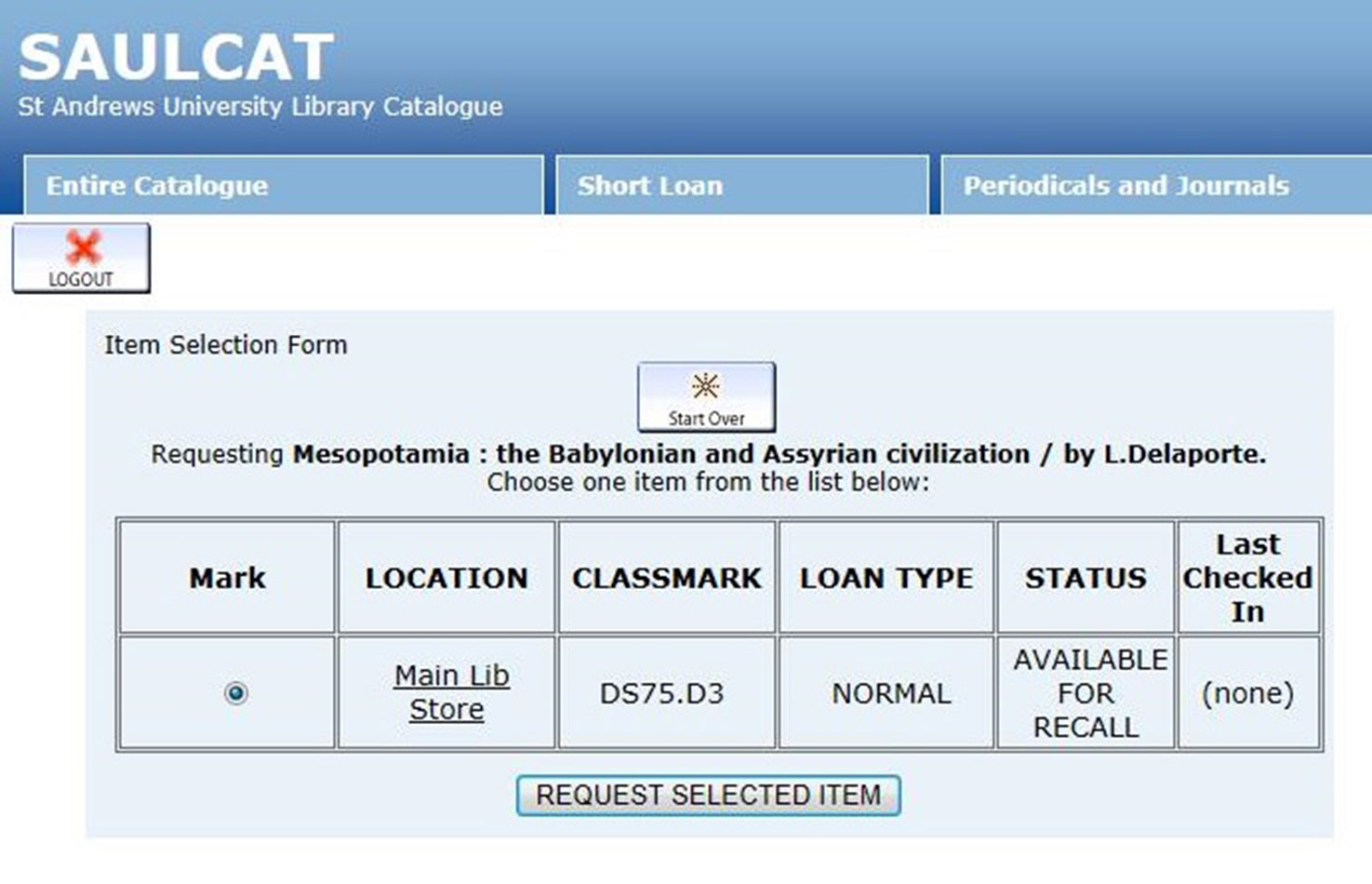

Bingo! Here’s my book, and no wonder I couldn’t find it, for the online catalogue shows that it’s a Library Store item. As a reader, I don’t have access to this area, so need to recall the book instead. Unlike 1972/73, I don’t need to speak to a member of staff at the counter, but can recall it myself via the online catalogue.

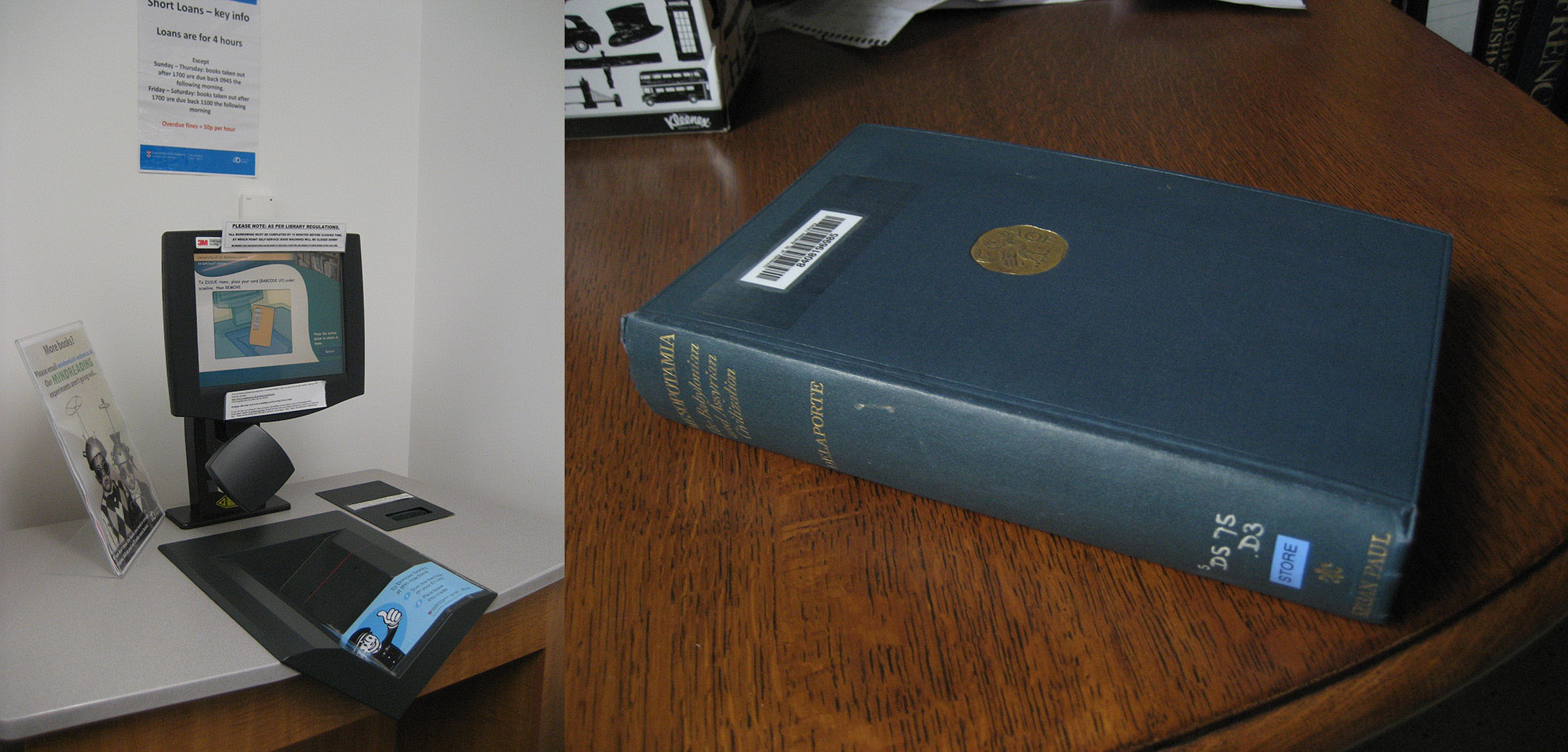

This done, I then simply awaited a notification email advising me that the book was ready for collection, and collected the book from the holding shelf in the Short Loan area on level 2, using one of the self-issue machines to check it out.

My feelings are that the whole process of borrowing a library book today is a lot more impersonal than in 1972/73, there being less contact with library staff; of course the self-service method for borrowing frees up library staff to engage with readers in new ways. It’s easy today to check the online catalogue, rather than the numerous paper catalogues readers had to peruse some 40 years ago. Who knows what will have changed in another 40 years? Will there even be physical volumes on the shelves …. ?

BA

My thanks to Jenny Evetts, Marjory Park, Janet Aucock and Martin Barkla for their help in researching various parts of this blog post.

I remember how tiring on the arms a day's research could be, lifting heavy catalogues off shelves. The St Andrews Page Catalogues were not too heavy, but the old British Museum Reading Room had heavy catalogues tightly packed - really exhausting, and you sometimes had to queue for access to your desired catalogue volume!

Well, how that takes me back! I particularly liked the illustrations and photographs. (I was a student 1959-63)

As an x-librarian (in Exeter, not St Andrews) I loved reading this post - so many memories of different systems and buildings designed to accommodate those different systems - happy trip down memory lane!