Reading the Collections, Week 14: George Herbert, The Temple (Cambridge: Thomas Buck and Roger Daniel, 1633)

Although I thought that the work of George Herbert was all new to me, I found that I already knew some of his poems almost by heart, having sung the hymns “Teach me, my God and King“, “King of Glory, King of Peace” and “Let All the World in Ev’ry Corner Sing” from a young age, but without taking a great deal of notice of the name of the person who wrote the words.

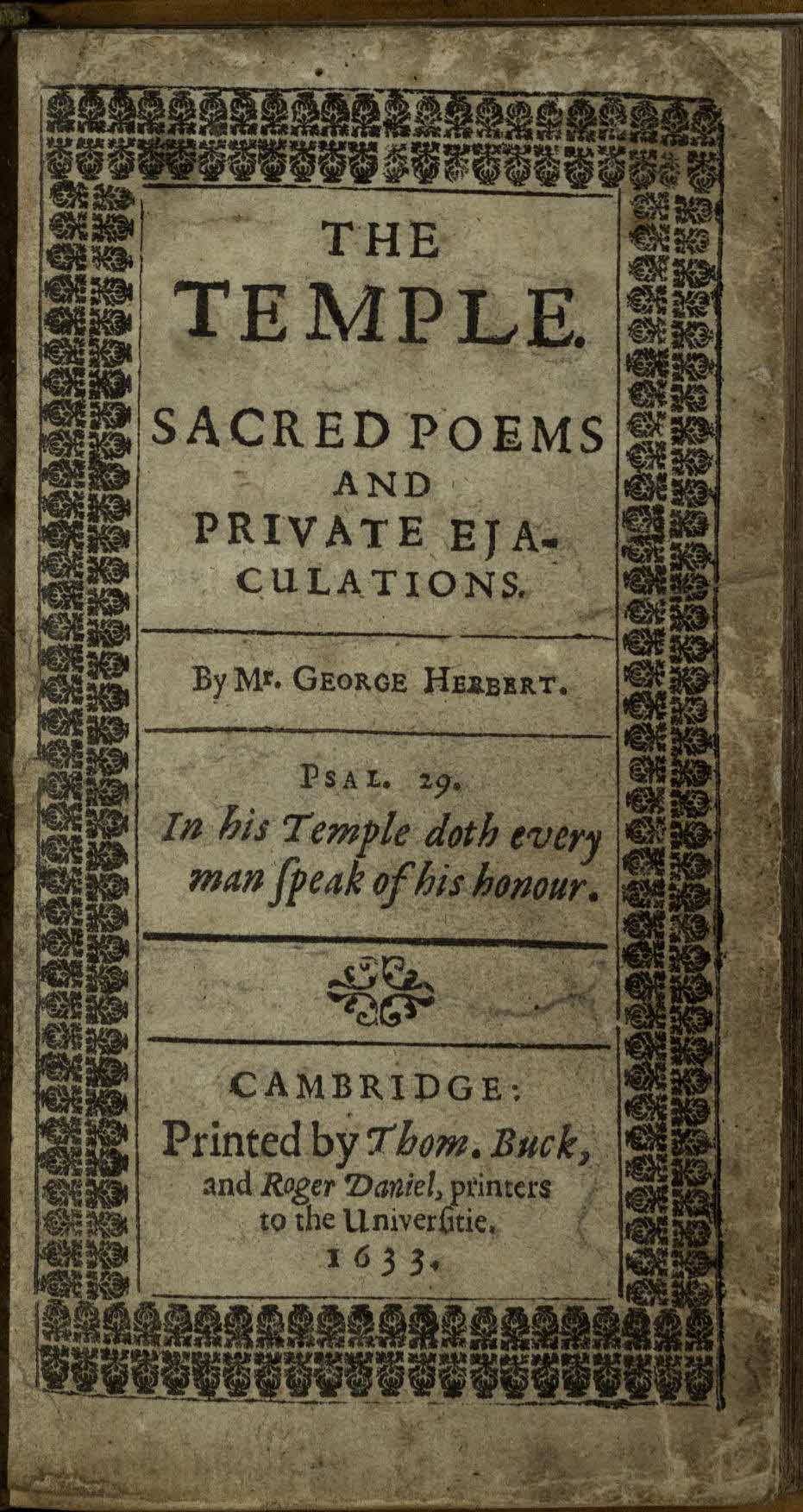

The 1633 first edition of George Herbert’s The Temple is a recent acquisition for Special Collections. A small duodecimo volume, we purchased it earlier this year to fill a longstanding gap in the collections, taking the opportunity to strengthen our early 17th century holdings from both an English literature and a printing and book history point of view. The purchase of this very significant book by one of the greatest of English devotional poets was made possible through the generous support of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

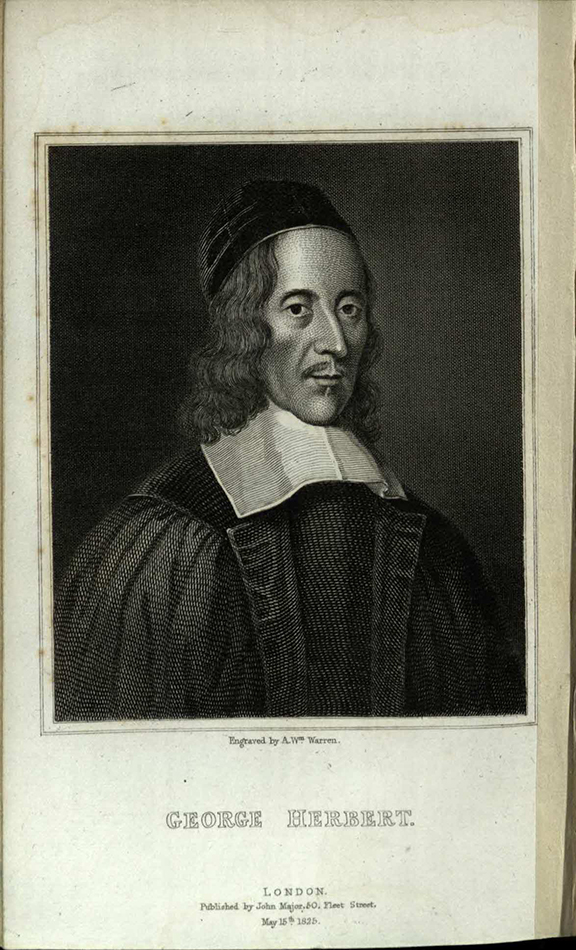

Born in Montgomery in 1593, Herbert was the seventh of ten children. His father, Richard Herbert (a descendant of the earls of Pembroke) died when George was three, leaving his mother, Magdalen, to bring up seven boys and three girls on her own. One of Magdalen’s close friends was John Donne, who preached her funeral at St. Paul’s. Magdalen’s hospitality was perhaps one of the sources for Herbert’s poem, “Love (III),” in which the reluctant sinner is invited to Love’s table to dine without conditions, but fully accepted as a guest, without snobbery:

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked anything.

The family moved to Oxford, and then to London, where George went to Westminster School and then on to Trinity College, Cambridge. By 1616 he was an MA and a Fellow of the college. In 1619 Herbert was appointed to the prestigious post of Public Orator of Cambridge, but despite having good prospects of achieving high public office, in 1624 he left Cambridge and decided to “enter into Sacred Orders”. In his autobiographical poem “Affliction” – which was probably written between 1624 and 1630, when Herbert settled at Bemerton in Wiltshire and was ordained as a priest – he expresses doubts and worries about his future, and articulates his struggle with worldly ambition:

Now I am here, what thou wilt do with me

None of my books will show:I reade, and sigh, and wish I were a tree;

For sure I then should grow

To fruit or shade.

Herbert had been writing poems since he was a teenager. In 1610, aged 17, he sent his mother two sonnets with a letter saying, “My meaning is in these Sonnets to declare my resolution to be, that my poor Abilities in Poetry, shall be all, and ever consecrated to God’s glory”. None of Herbert’s poetry in English was published during his lifetime, but he hoped it would act as consolation ‘of any dejected poor soul’. When Herbert was dying aged just 39, he arranged for his handwritten book of poems to be taken to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, the founder of the religious community at Little Gidding. Ferrar was instructed by Herbert on his deathbed either to burn or publish the manuscript “for I and it are less than the least of God’s mercies.” The collection, entitled The Temple was an instant success, went through at least 11 editions up to 1695. This work established Herbert as one of the foremost religious poets in the English language.

The first edition of The Temple was printed by Thomas Buck, the Cambridge University Printer. Buck was a careful printer, who employed heavy punctuation and regularised layout of lines and stanzas. The collection of poems, printed with an index of titles, was obviously meant to be carried around by the reader, and used for reflection and prayer. The first edition of The Temple also contains the first example of an index to an English book of poems. Although it does nothing more than list the titles of the individual poems in alphabetical order, the index was innovative in that it makes the book available for a specific, devotional use. A reader could use the index to find poems on a given religious topic appropriate for meditation: “Avarice”, “Conscience,” “The Crosse,” “Easter,” “Love,” “Mortification,” “Sunday,” “Ungratefulnesse.” The index (from the Latin for “forefinger” subsequently became instrumental to the use of books. It made the contents usefully accessible but also identified the book’s central subjects.

All of Herbert’s poems (except some of the Latin poems he wrote in his youth) are on religious themes and his reputation rests chiefly on the poems in the middle section of The Temple, called “The Church”.

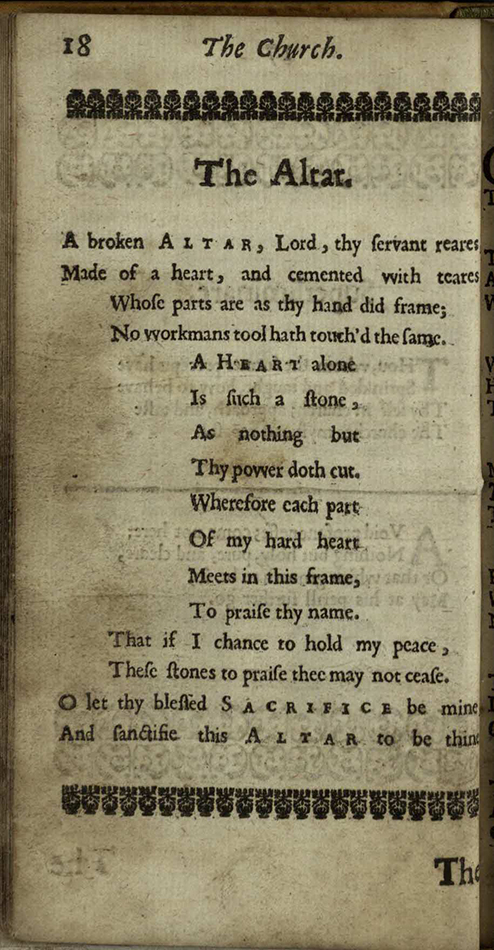

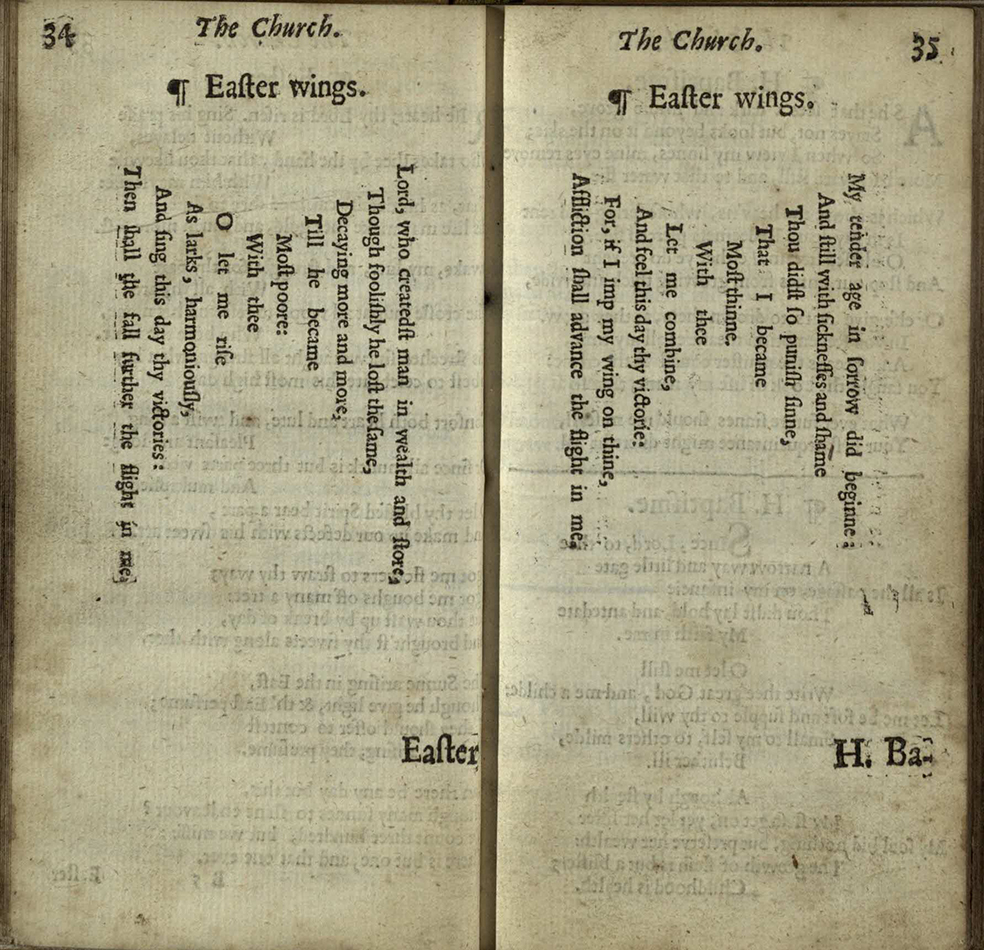

Among these are the well-known pattern poems, “The Altar” (in which the lines are arranged into the shape of an altar) and “Easter Wings”, in which the lines represent the shape of wings on the page:

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store,

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore:

With thee

Oh let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me.My tender age in sorrow did beginne:

And still with sicknesses and shame

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne.

With thee

Let me combine

And feel this day thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine

Affliction shall advance the flight in me.

The lines mimic its subject, suggesting two birds flying upwards, with their wings spread out, representing the ultimate flight of humanity when Christ claim his followers.

Herbert’s poems are full of tortured self-doubt, agonised examination of his motivations, and complaint. Often these are resolved in a tidy couplet at the end of the poem, recalling the poet to God’s promises or presence, but Herbert sometimes rails against and agonises about his vocation. Charles I read Herbert’s poems when imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle before his execution, while the moderate nonconformist Richard Baxter spoke for many seventeenth-century readers when he praised The Temple as a text in which ‘‘Heart-work and Heaven-work’’ were combined. Herbert is a writer whose work fascinates and inspires and has the potential to give spiritual comfort to readers from all traditions.

Gabriel Sewell

Head of Special Collections

The claim that "The first edition of The Temple also contains the first example of an index to an English book of poems" is, I believe, mistaken (provided I understand what is meant by "index"). Even Tottel's Miscellany of 1557 - generally thought to be the first poetic anthology in English - contains a table of first lines at the book's close.

Dear Jeremy, thank you for your comment. You are indeed correct that Tottel’s Miscellany contains an index (although this didn’t appear in the first edition of 1557), and we’re pleased that you spotted our error that the first edition of The Temple was not the first work in English to contain an index.