Where we find new old books, chapter 2: a new 15th century fragment joins a fragmentary history

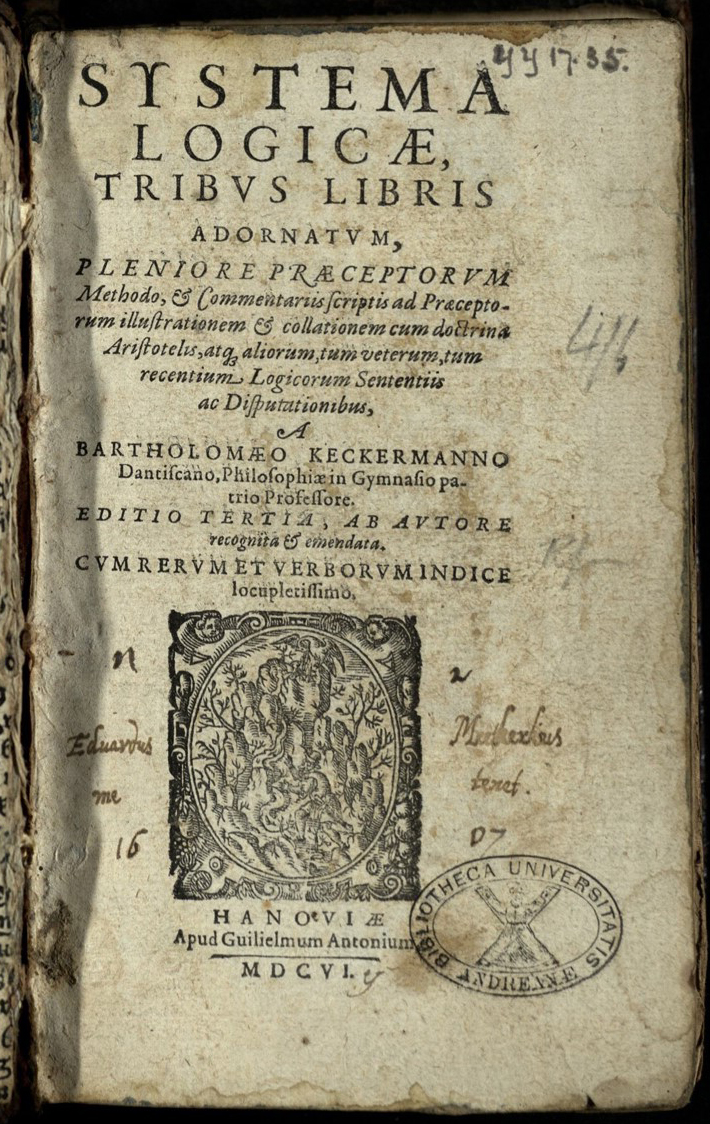

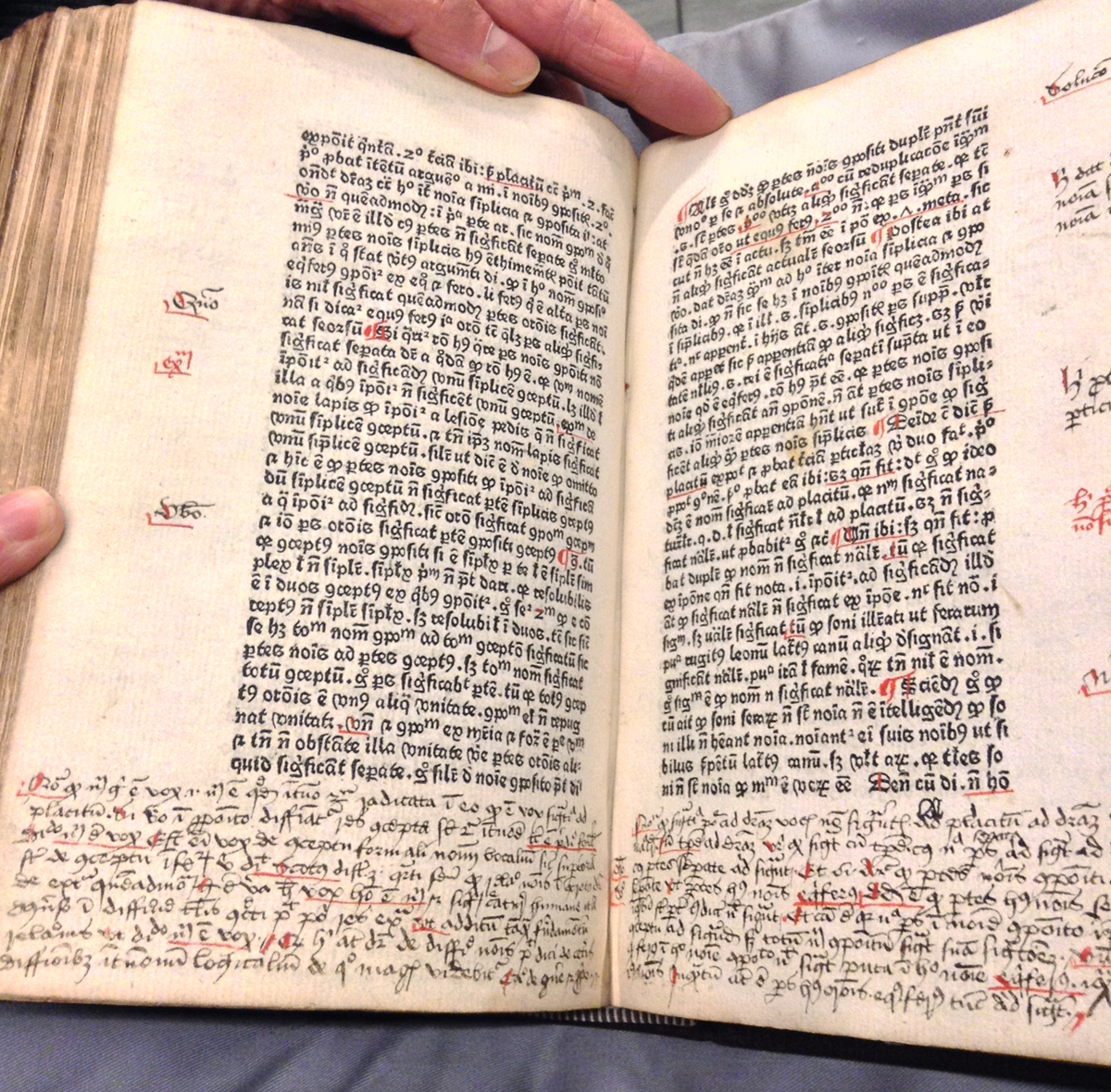

Around a month ago Liza DeBlock (one of our MLitt in Book History students) pulled from the shelf this very interesting book during her regularly scheduled bibliography lab hours:

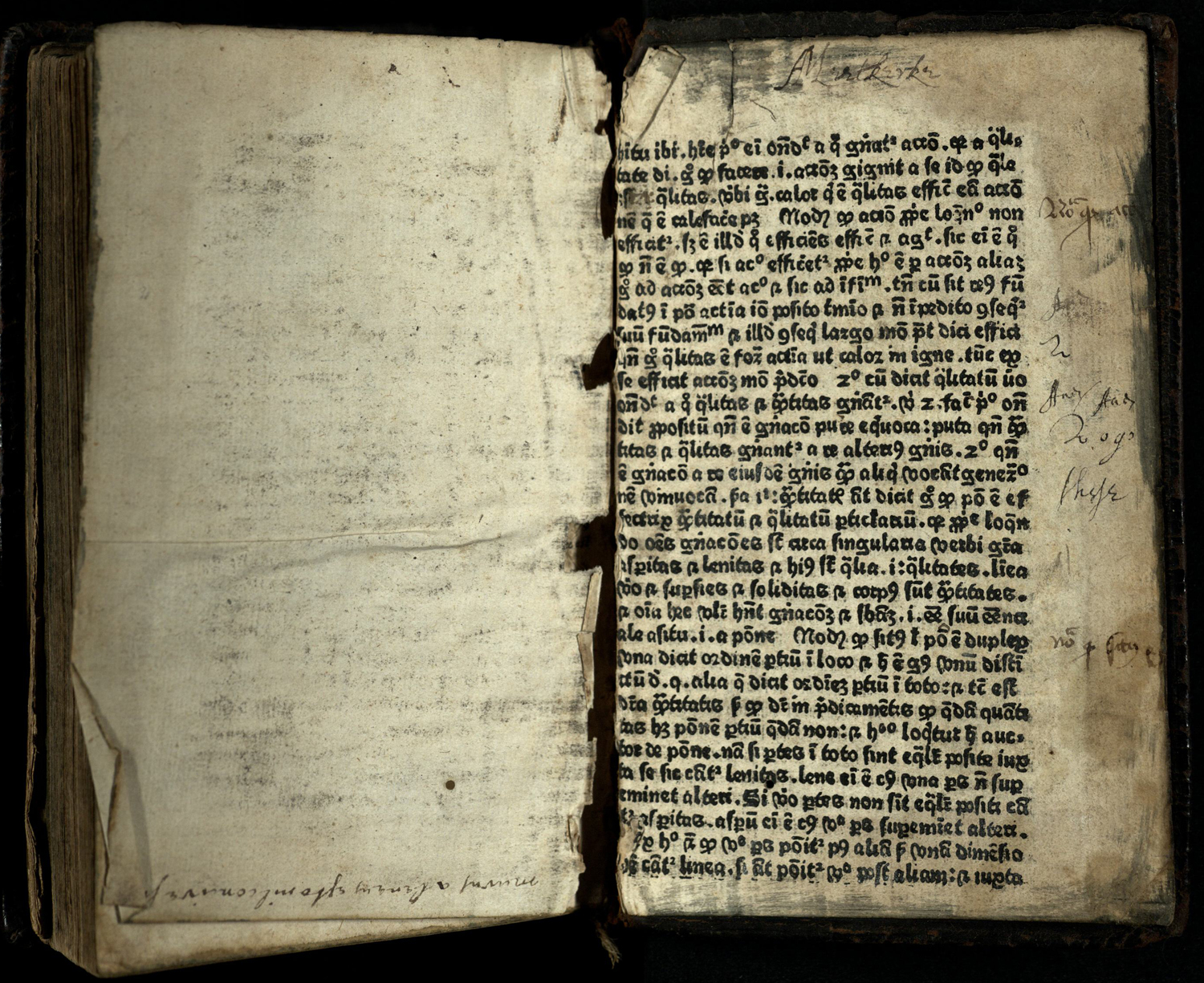

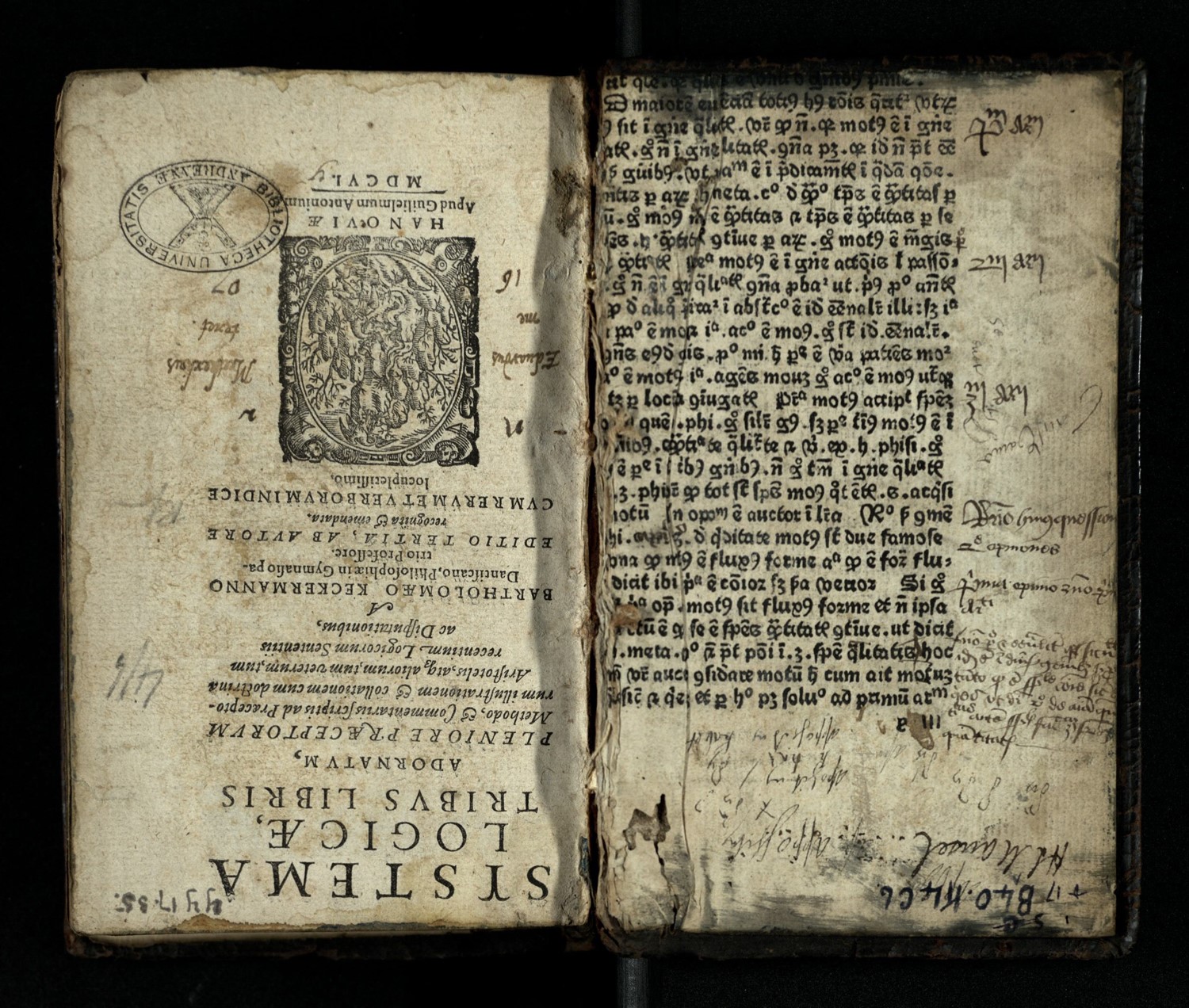

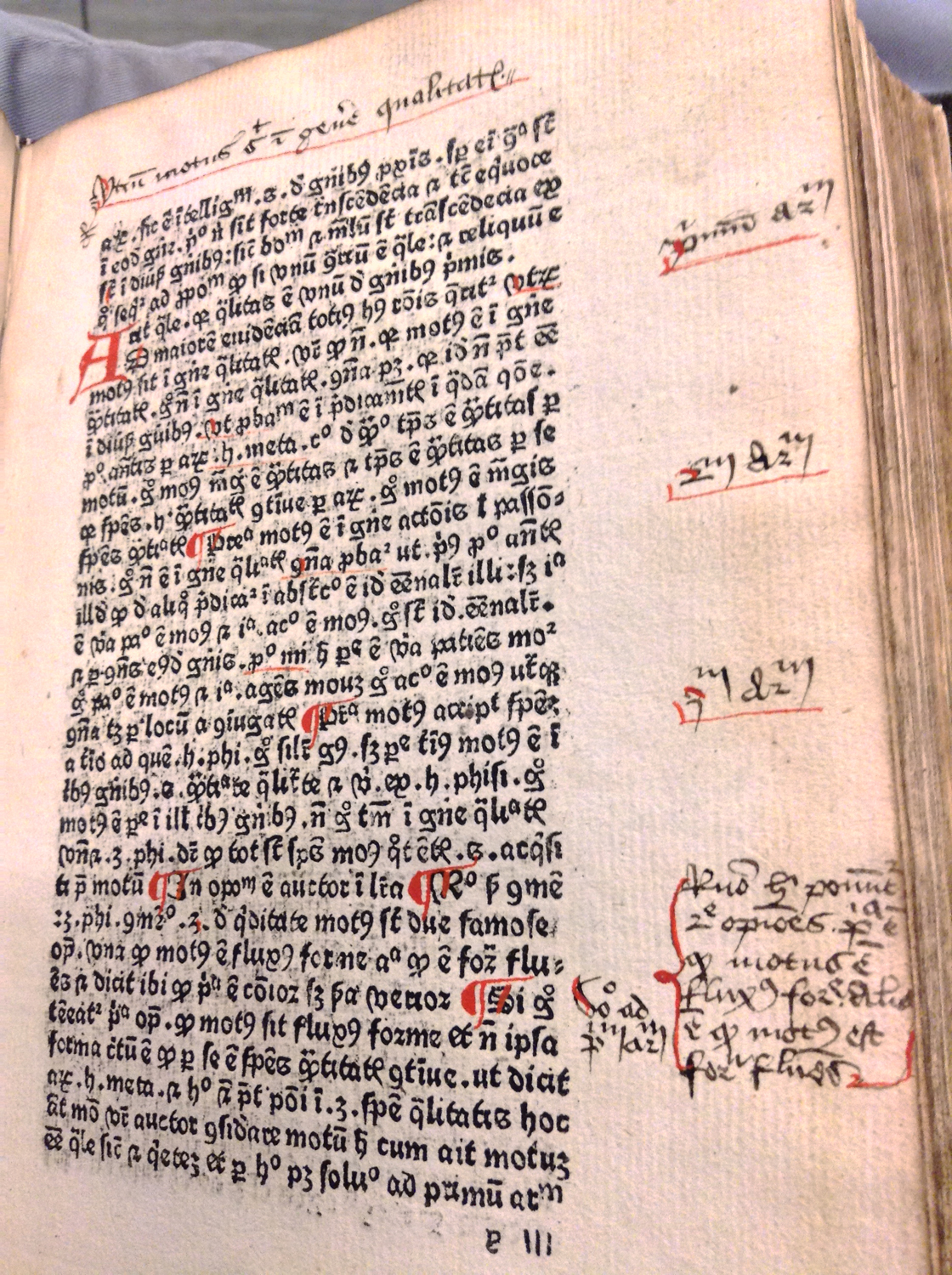

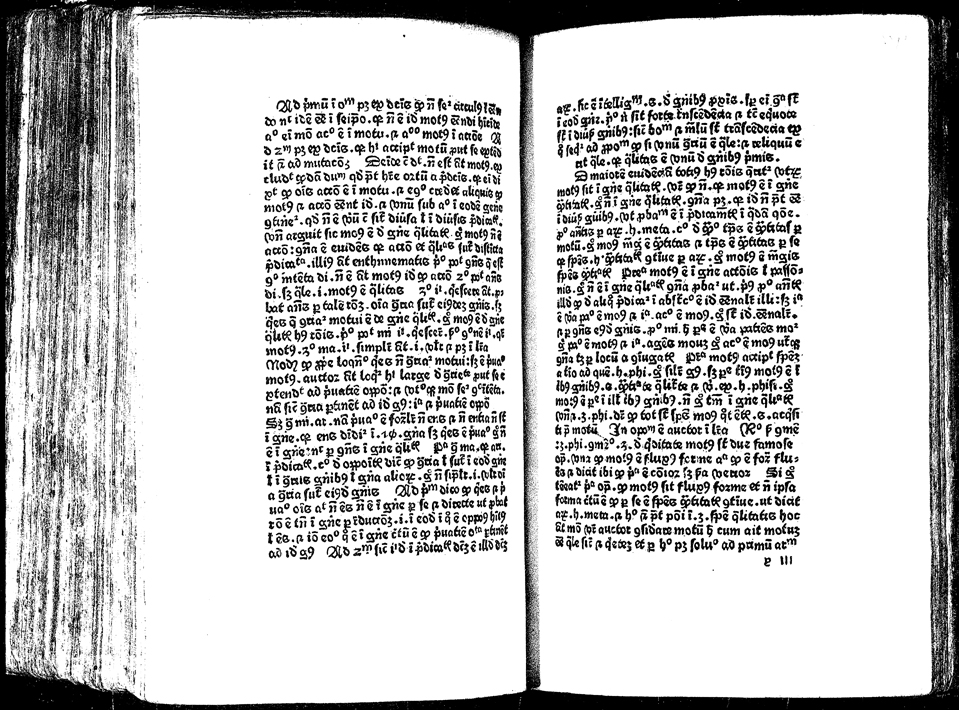

This third edition of Keckermann’s Systema Logicae was a nice find, with loads of contemporary and 19th century provenance to trace after assembling the bibliographical record (see below); however, as I was peering over her shoulder to check her work I was drawn to the pastedowns (both front and back):

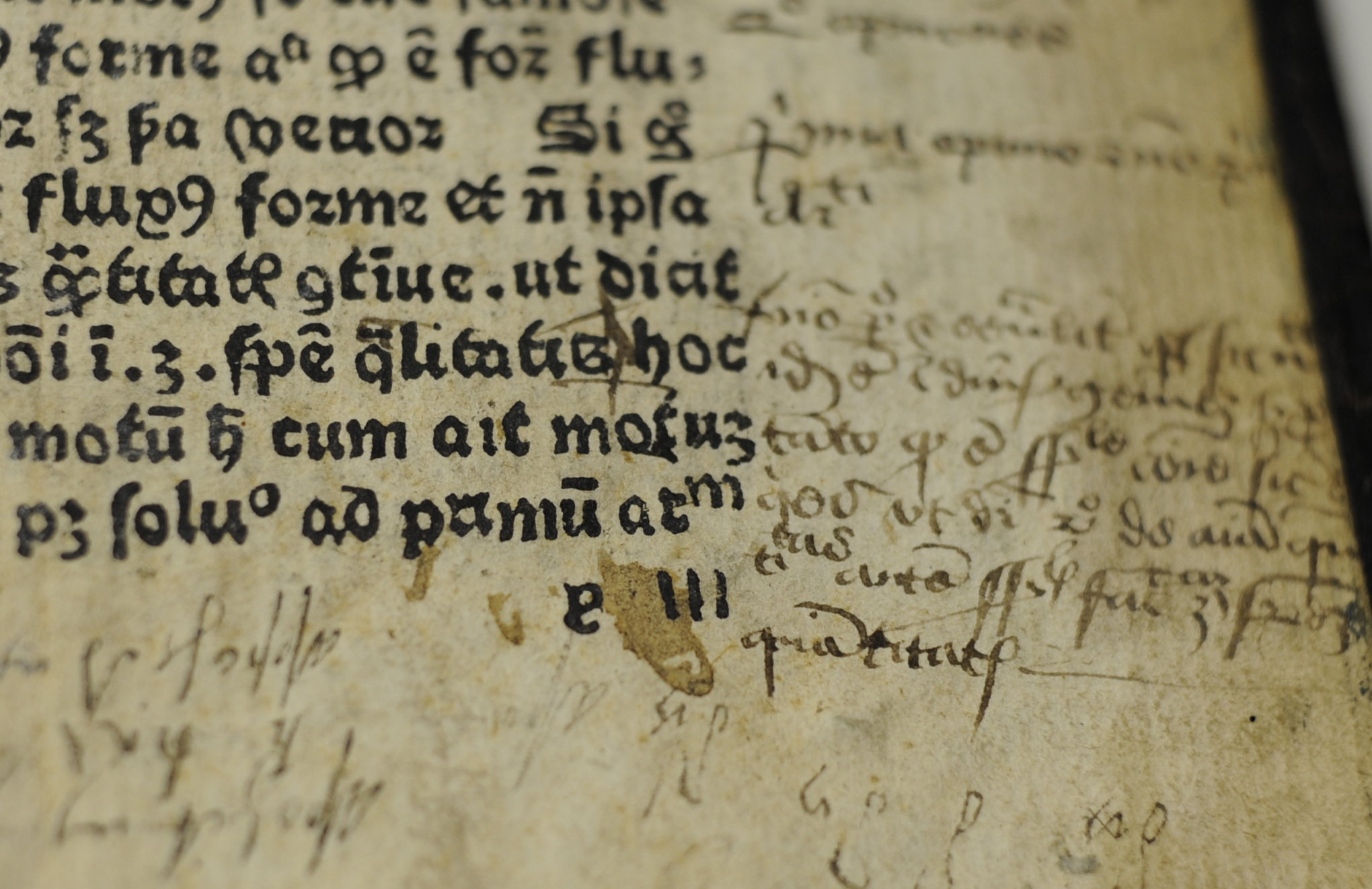

The type, the mis-en-page, the copious abbreviations throughout the text on these fragments immediately threw up incunabula red flags; this had to be leaves from a 15th century book! But, where to begin? There was very little hint on the fragments to tell us what this text might be, no running-titles or even very few un-abbreviated words in the text to try some good old-fashioned keyword searching; the frustrating fact that these two leaves were from the middle of what looked to be quite a long book meant that there was very little to go on. I spent a full afternoon with my Cappelli in-hand pulling out three- and four-word phrases to try to find a possible match for the text which would then help in identifying potential editions. This resulted in absolutely no finds at all; this text was too dense or too obscure for this kind of matching.

My next step was to put a call out for help to Dr Falk Eisermann, Referatsleiter of the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW) in Berlin and general incunabula-guru, who immediately got back to me with the supposition that it was probably English and most certainly 15th century, but a very odd type. One of his staff, Martina Nickel, did some quick work and narrowed down the field to only one likely candidate, based on the fact that this was probably English, a 32-line page, inclusive of at least a signature “y” and heavily abbreviated philosophical text: a fragmentary witness of the 1481/2 St Albans printing of Antonius Andreae’s Scriptum in logica sua (GW 1673 & ISTC ia00593500). This was rather exciting news, as St Andrews isn’t exactly flush with 15th century books printed in England; in fact, this discovery would increase our English incunabula holdings by 25%!

This got everyone excited, and the next step was to confirm these two leaves against a complete copy. According to ISTC, the only complete copy of this work recorded is, in a rather quirky turn of history, held at Norwich Public Library (all other copies listed as “fragments” or “imperfect”). Now, this was admittedly a misstep on this bibliographer’s part: had I taken the extra step to check the ESTC record for this book I would have seen that not only is Jesus College, Cambridge’s copy of this work nearly complete (instead of the ISTC red flag of “imperfect”) and that the catalogue record for their copy was exceptionally complete (which was, I later found out, done by Liam Sims, now of the Rare Books Department of the CUL), but that ESTC also linked through to an EEBO scan of the Jesus College copy. However, “hindsight is always 20/20” and all that, I chose to instead get in touch with Norwich Public Library to see if I could find someone sympathetic to my cause and help me get a positive match of our two newly discovered leaves.

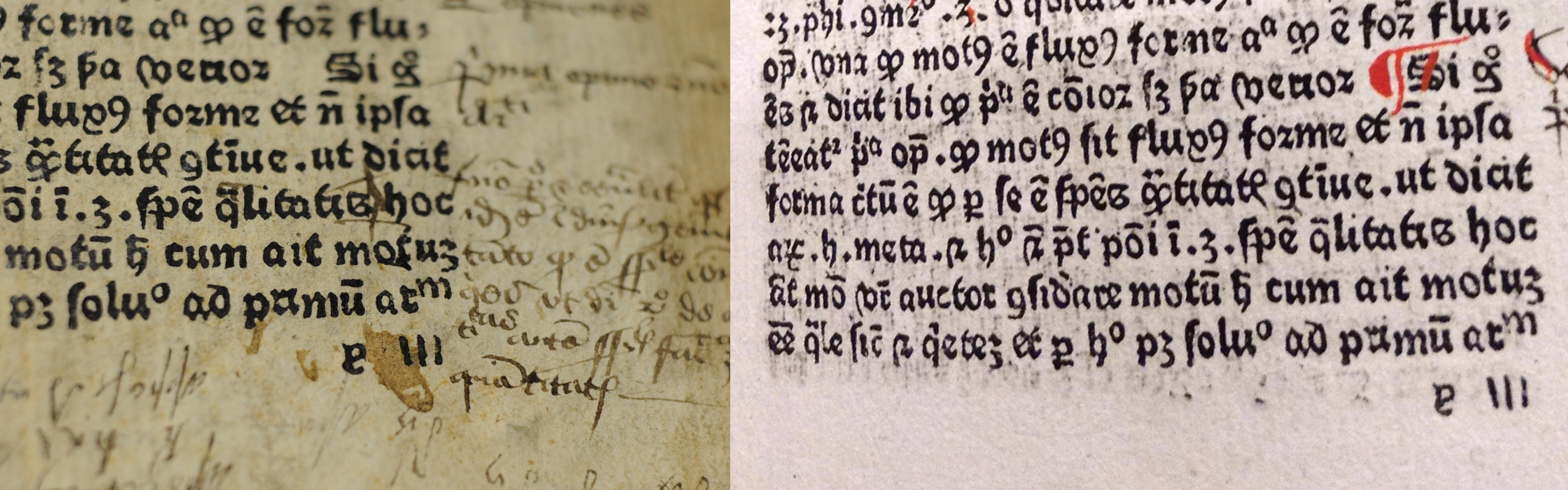

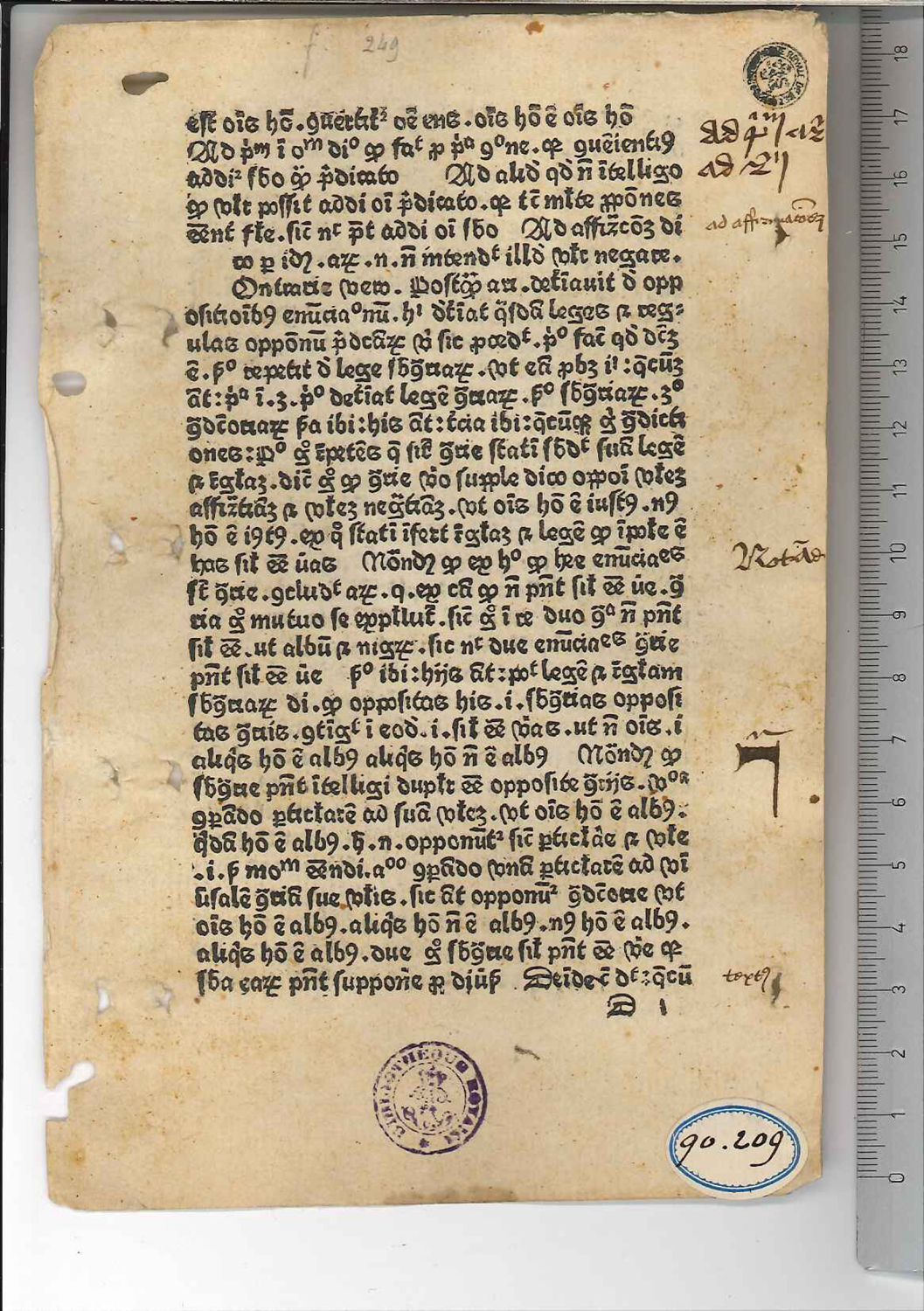

After some phone hurdle-jumping, I was finally put in touch with the wonderful Clare Agate who, admittedly very inexperienced when it came to 15th century books, enthusiastically agreed to search their copy for a match to some images I sent along. Again, within a few hours, Clare came back to me to confirm that our leaf y3 matched their leaf exactly, and that our other leaf (now used as a rear paste-down) was the recto of leaf y5. Armed with this knowledge we could now set out to enter our newest incunabula into our online catalogue, and to also record our copy’s individual history into the Material Evidence in Incunabula database (in progress). Here’s a quick canned history of how this book, printed in 1606 in Germany, came to be the vessel in which these very rare leaves have survived:

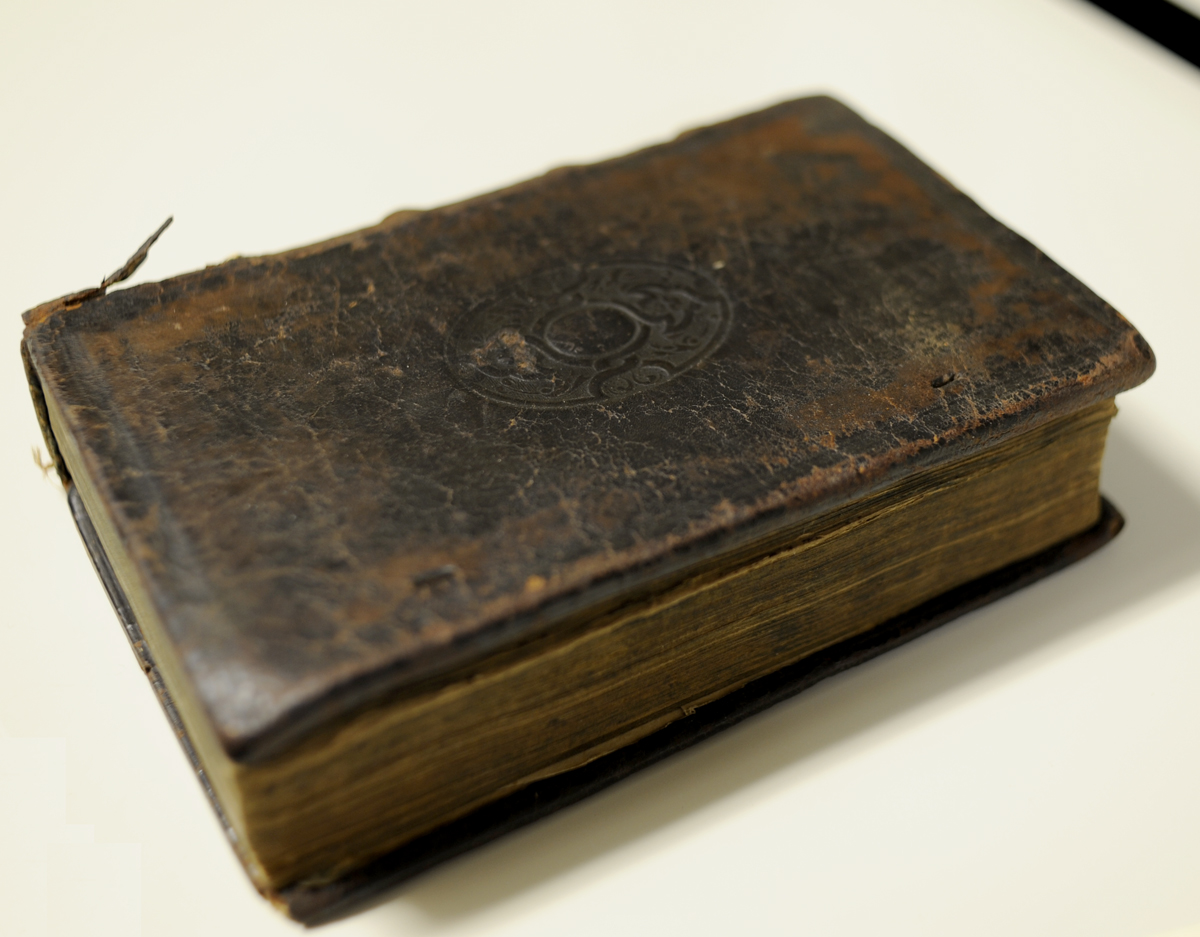

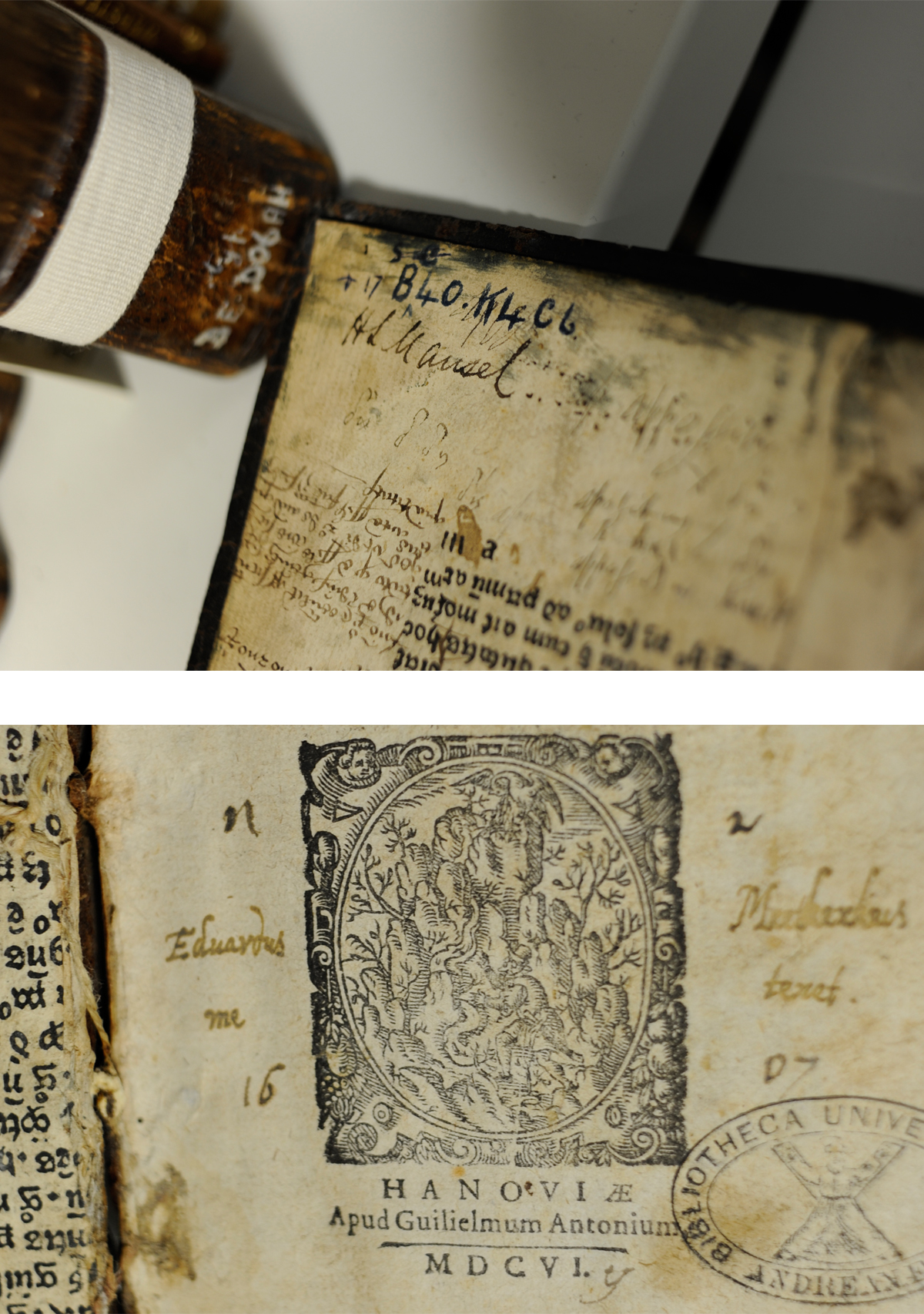

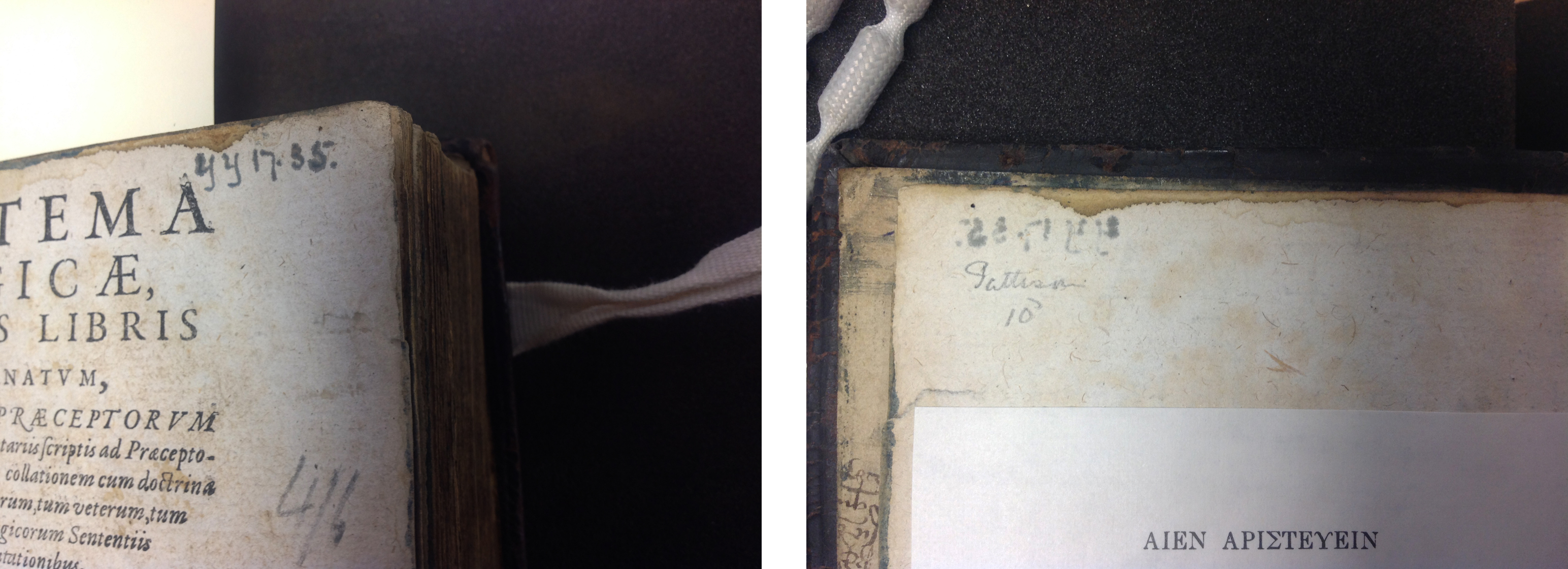

This third edition of Keckermann’s work was printed in Hanau in 1606. In 1607, a 17 year-old Edward Meetkerke purchased this book, most likely in Oxford, and had it bound there (***update: the emblem stamp in blind used on both boards has been identified by Dr David Rundle @DrDavidRundle as a match to plate xxxiv in David Pearson’s Oxford Bookbinding 1500-1640) and it was at this time that these two 15th century leaves, which had probably been purchased in bulk as waste-paper for packing bindings, were added to this work. This book passed to his son, Adolphus (whose signature “AMetkerke” is found on the back pastedown, or y5 of our new incunabula), who was also an Oxford man. The next clear mark of ownership is the signature of “HL Mansel” on the front pastedown, this being Henry Longueville Mansel, professor in Aristotelean (and other) philosophy at Magdalen College and later dean of St Paul’s; this book very well could have remained in Oxford since its original purchase in 1607.

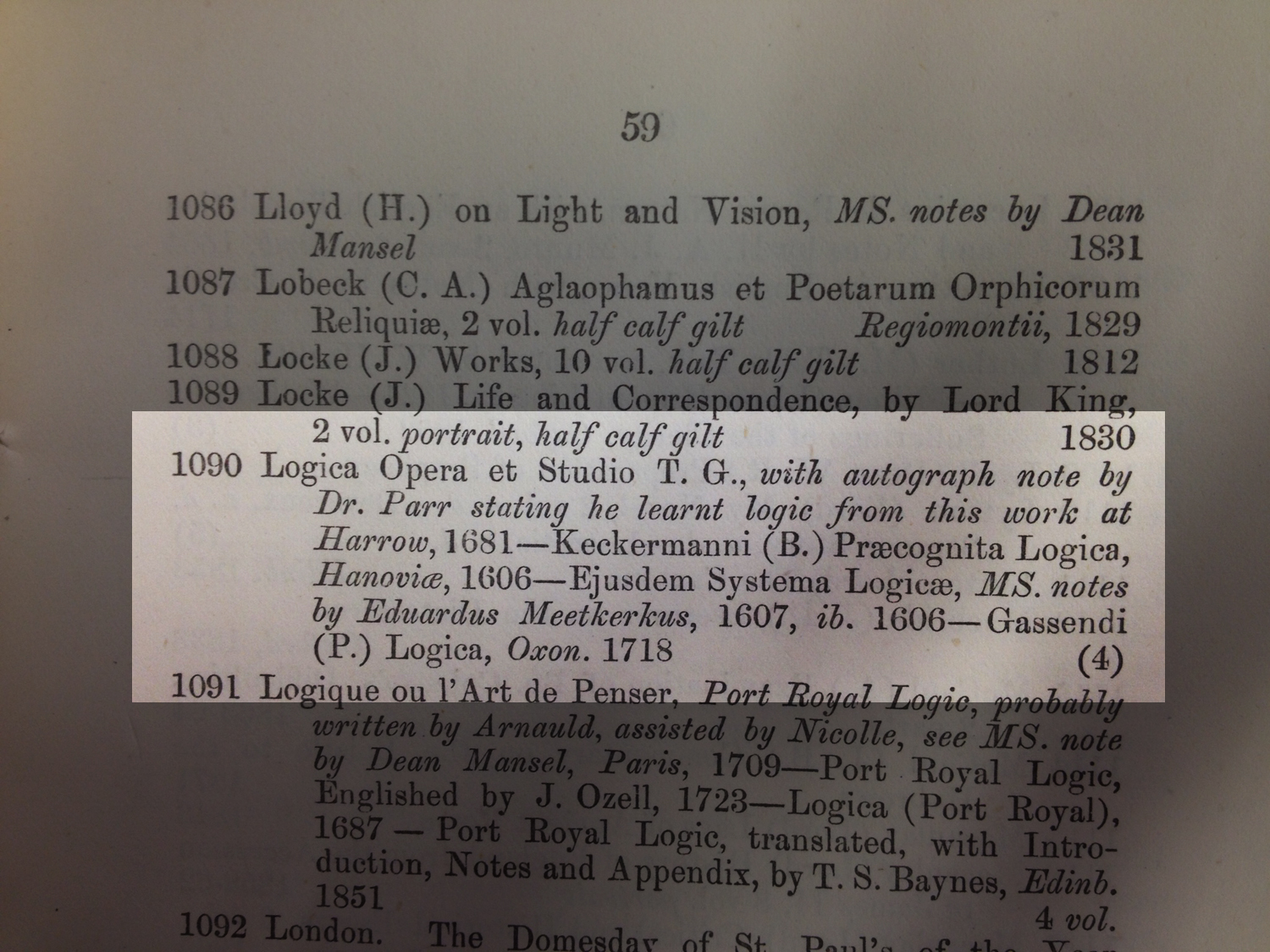

Mansel’s books were auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 1872, a year after his death, and sure enough (with humongous thanks to Jeremy Dibbell for pointing the way and Julie Blyth at the Library of Corpus Christi College, Oxford for checking their copy of the sale catalogue!) this work can be found at lot 1090, with mention to Meetkerke’s inscription. The final mark of provenance found in this volume is the combination of an old pressmark at the head of the title page (yy17.35) and a faint pencil inscription on the verso of the title page “Pattison 10d”.

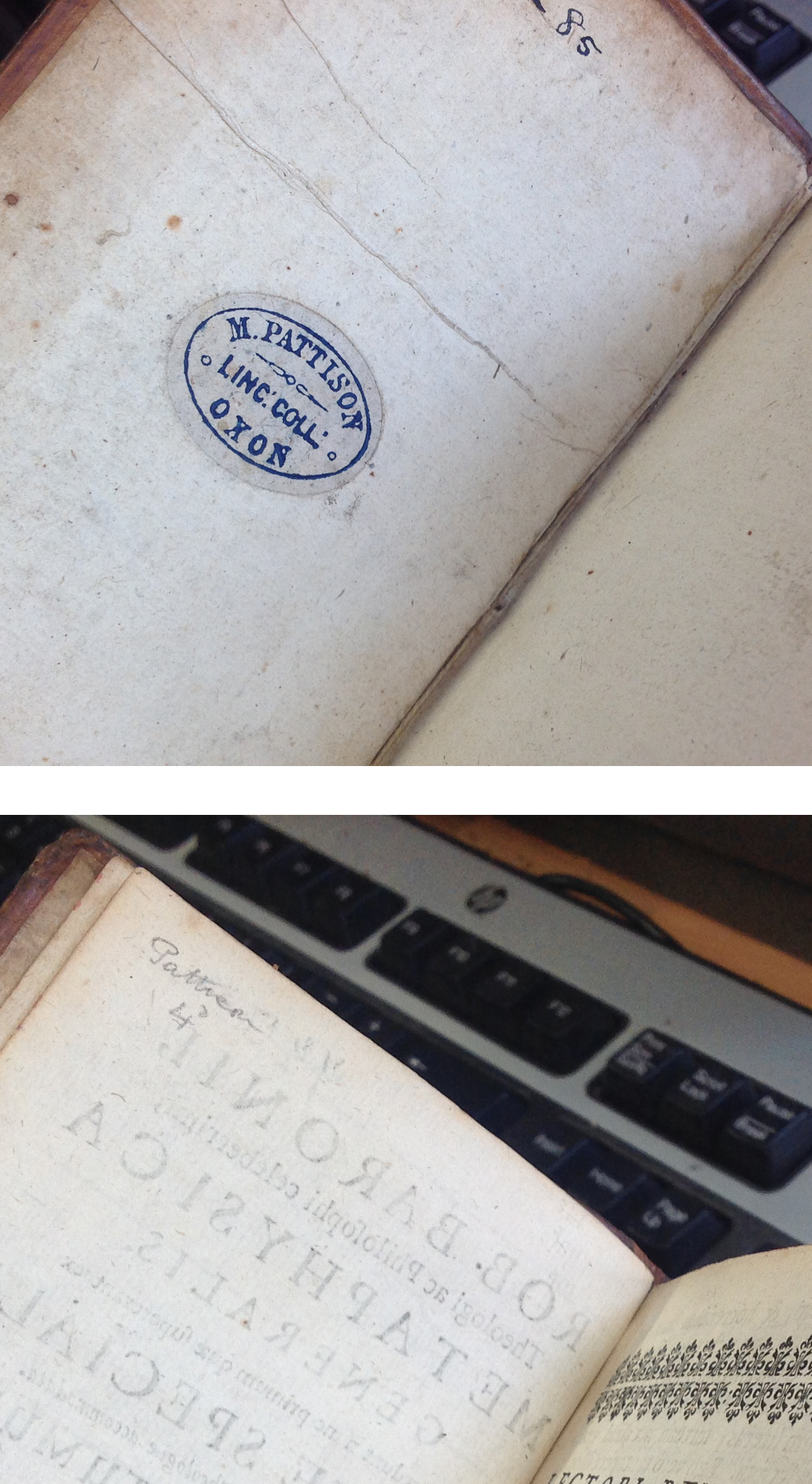

At first, I though this mark was too cryptic to decipher, I tried a few searches across authority records and historic pressmarks, but was striking out, until yesterday, by complete chance, Liza happened to pull another book for cataloguing with the same pencil markings but also with a most helpful booklabel of “M. Pattison Linc. Coll. Oxon” and with an embossed book stamp on title page “Mark Pattison Lincolc College Oxon.”, clearly from the collection of Mark Pattison, Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford. With some quick Twitter-based help of Bob McLean (@bob_mclean) and Edmund Brumfitt (@ebrumfitt) a catalogue of the Pattison sale (Sotheby’s, Wilkinson & Hodge 27 July 1885) was found.

—

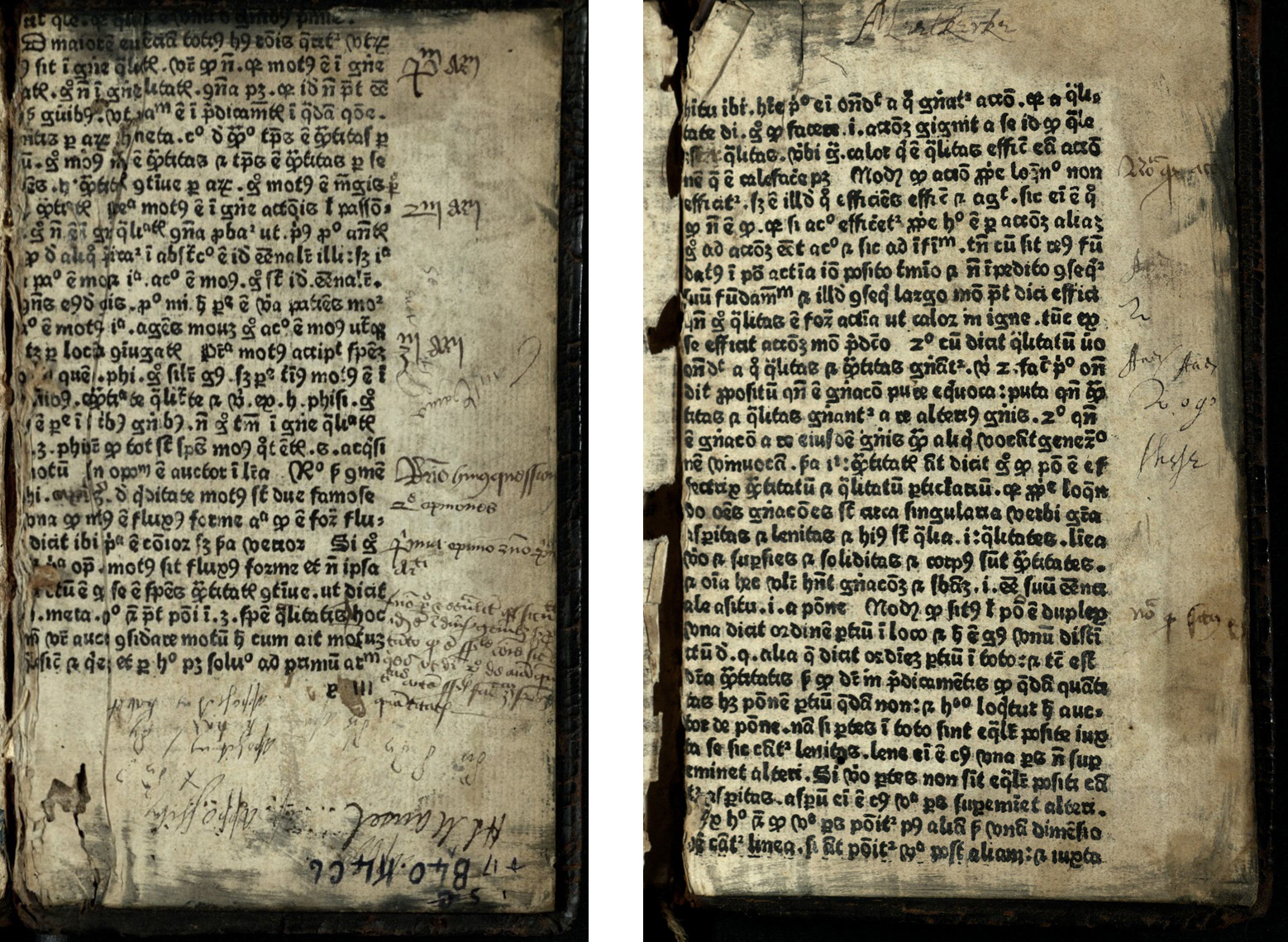

How these two 15th century leaves came to survive as waste makes for some intriguing supposition as well. We know that this collection of philosophical works by Antonius Andreae, numbering over 330 leaves, was the longest book printed in St Albans by the “schoolmaster printer” and one of two works on Aristotle issued by the press. It was also posited in 1924 by Charles Henry Ashdown that the press at St Albans not only serviced the needs of the Abbey and School in town, but also the book-needs of the students of Cambridge. Whatever the case, it is clear that this work by Andreae was heavily read and digested by its readers: all copies recorded and seen for this post bear contemporary marks of readership and the extant state of copies (see census below), almost completely fragmentary and having been removed from bindings, illustrates the digestable nature of this particular edition (several later 15th century editions of Andreae’s work were published on the continent, but no others in England). Clearly, at some point in the 16th century, copies of this book were pulped and sold as waste-sheets and made their way into late 16th and 17th century bindings, in which the largest number of witnesses to copies of this unique edition have survived.

In order to obtain a clear picture of the state of all extant copies of the St Albans edition of Scriptum in logica sua, I canvassed the libraries that have reported their holdings to either ISTC or ESTC for images of their fragments, and below is a near-complete census of all extant copies of this edition.

CENSUS of GW 1673 & ISTC ia00593500: Antonius Andreae. Scriptum in logica sua. [St Albans: Schoolmaster Printer, 1481/2]

- Norwich Public Library: Ca32 – only complete copy recorded;

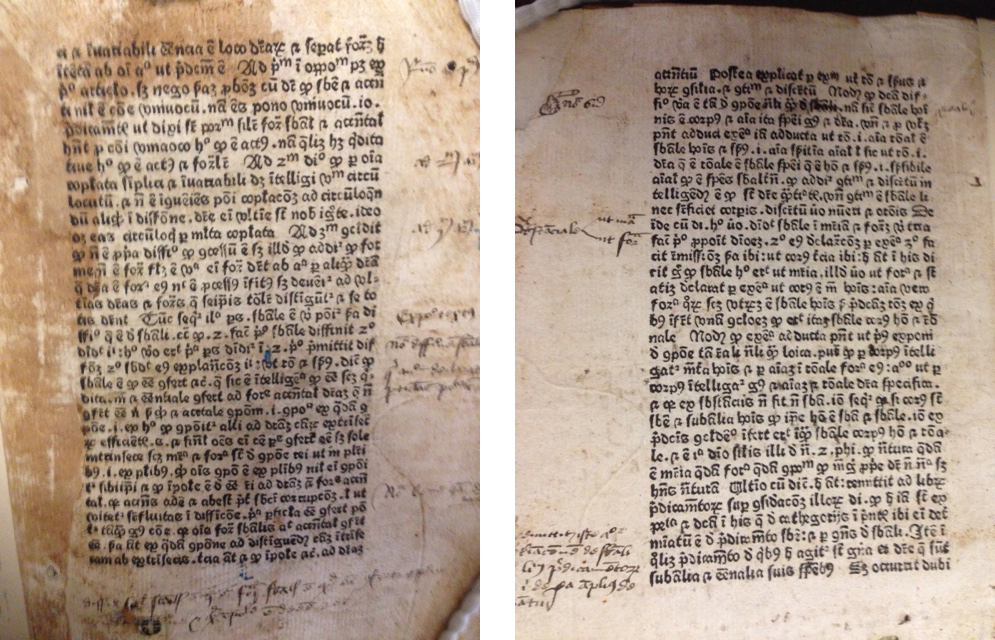

- Jesus College, Cambridge: 3.49 – nearly complete copy, wanting leaves a1 and a3;

- Wadham College, Oxford (unseen): Unknown classmark – apparently nearly complete copy, wanting all of gathering “L”;

![Leaves [est]2r and [est]7v from the Cambridge University Library copy. Image courtesy of Cambridge University Library.](https://special-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2015/05/cul-provenance.jpg?w=300)

- Cambridge University Library: Fragments.3[3633] – 28 leaves, or fragments of leaves, extracted from a binding: leaves z(2,4,5,7), [et](2,4,5,7), [con](2,4,5,7), [3 lines](2,4,5,7), est(2,4,5,7), E(2,7), L(1,2,7,8) and M(1,8);

- Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België/Bibliothèque royale de Belgique: INC B 396 – fragmentary, 14 leaves only: D1, D3, [D6]; E4, [E5]; F2, F4, [F5], [F7]; G1, G3, [G6]; H2, [H7];

- University of St Andrews: r17 BC40.K4C6 – fragmentary, 2 leaves only: y3 and y5;

- Merton College, Oxford: MER 111.E.29 – fragmentary, removed from a 16th century binding in 1918, 1 leaf only: u5.

The fate of at least three copies of this book, being used as binding waste on later works, hints at the fact that there are surely other leaves and fragments lurking in 16th and 17th century bindings within historic collections, waiting to be identified and perhaps paired up with their long-lost edition-mates.

The importance of the unearthing of this new fragmentary witness of an obscure 15th century book may seem small, but the recording of the presence of another copy of any early printed book has an impact on the perception of how individual copies of an edition circulated and how a work may have risen and fallen out of fashion over the centuries. Cataloguers and bibliographers often do not have the time and resources to identify random pastedown or waste fragments found in the books they are working on; but, if we take the time to ask around, and, with a little help from our friends (cheers, Joe Cocker), we may just find something truly special.

To that end:

The identification of our newly uncovered fragments, and the above census would not have been possible without the support of the wide library and antiquarian bookselling network which made itself available through e-mail and Twitter. Special thanks go to Dr Falk Eisermann and his team (GW), Clare Agate (Norwich Public Library), Dr Emily Dourish and Liam Sims (Cambridge University Library), Dr Julia Walworth (Merton College, Oxford), Karin Pairon (KBR), Julie Blyth (Corpus Christi College, Oxford), Jeremy Dibbell (University of Virginia, @JBD1), Bob McLean (University of Glasgow, @bob_mclean) and Edmund Brumfitt (@ebrumfitt).

–Daryl Green

Rare Books Librarian

So it was bought at the Pattison sale for 10d? Do you know by whom, and what lot no.?

Will try to get the lot no. on Friday when I see the catalogue at Glasgow. I suspect it was us that bought it, as well as others, but need to dip into the archive to confirm...

Great detective story and well done on the find. Just two thoughts. (1) Aren't the fragments in CUL and in Brussels from the same copy of yours (judging from some of the marginalia)? And (2) Is not fully clear from the photo, but isn't the centrepiece on your binding Ker / Pearson xxxiv - ie Oxford? That gives you a place where your copy was probably broken up and you could check that with the bindings for the other fragments. Can't wait to hear more!

Hi there, (1) They look similar, but I wouldn't venture a positive match until all fragments can be looked at. I can get in touch with both again and ask for snaps of all their fragments to have a real comparison drawn up. (2) I'll check Ker/Pearson tomorrow for this reference and let you know! The Merton fragment was extracted from a dateable mid-16th century Cambridge binding, the CUL fragments don't have a record of what binding they were extracted from in 1918, and I'm not sure about the KBR copy...Cheers!

(1) Look at the form of 'a' in the Brussels copy and yours - variable forms in yours but strong similarities. And the ex libris in the CUL copy strikes me as being by the same hand. (2) Merton one does seem to have separate sets of marginalia and likely then to be from a different copy. Highly unlikely that one copy hung around (even less, moved between) booksellers / binders for more than a few months, let alone decades.

Hi David, Had a chance to look at both the Ker/Pearson volume and our book again, you can see the binding emblem in this image: https://twitter.com/ilikeoldbooks/status/598814133623066627 This does indeed look like a match, i.e. bound in Oxford, which is in keeping with the 1607 Meetkerke provenance. How the sheets got to Oxford is another question, and, again, why so late? As for the CUL and KBR copies, I certainly see similarities, too, but am not convinced until all fragments can be seen next to one another.

[…] by the St Albans printer. They did some painstaking work on reconstructing it and its context, and the post they have narrating the process is a testament to how research is done nowadays, using on-line resources, sending colleagues […]

Wonderful piece. You wrote: "there are surely other leaves and fragments lurking in 16th and 17th century bindings within historic collections, waiting to be identified and perhaps paired up with their long-lost edition-mates." Just today (24 Sept 2015) I identified such a bifolium here at Princeton. It is very close to the Merton College fragment in its annotations and manicule, and has strong similarities to the Cambridge group, as well. Unfortunately the precise binding source seems not to be known; it was in a box of stray leaves awaiting identification. Your work helped me add a new survivor to the census. Thanks. Eric White, Curator of Rare Books, Princeton University Library

Hi Eric, Oh, this is wonderful news, how exciting! In the past two months I've dug up and have been able to identify (with the help of the GW team, of course) three other incunabula fragments in bindings (new blog forthcoming next week on one) and I'm now getting as excited about incunabula fragments in books as I am about MSS fragments. Such a dizzying amount of material to sift through, but then when we turn up trumps like these fragments it's all worth it! Thanks for getting in touch with this news, Daryl Green, Rare Books Librarian

Princeton has ff. x3+x6, all 32 lines but cropped across the top and bottom and with the loss of the outer half of the text of f. x3. Majestic Bull's Head watermark in the inner margin. On closer look, the annotations are almost certainly the same as Merton College's, and the aforementioned similarity to Cambridge's is superficial. Eric White, Princeton

[…] over 50x20mm, displaying at most five lines of type, we had little to go on. So, just like the previous blog post in this series, we reached out to our friends Dr Falk Esiermann and Dr Oliver Duntze at […]

I think I found 16 3/4 pages (waste paper) of this work. Can I send you some scans of the leaves to confirm it? Best regards Wolfgang Derkau

Hi Wolfgang. Do you want to email the scans to us ([email protected]), and we’ll see what we can do. All the best, Briony Harding, Assistant Rare Books Librarian

Yes, please share the results! Eric White, Princeton

agreed, please share!

Just to update our readers. Wolfang Derkau has confirmed that with the help of Dr. Duntze from the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke in Berlin, he was able to identify that the eight leaves then in his possession were from this printing of Antonius Andreae’s 'Scriptum in logica sua'.

Another binding fragment has shown up, on the market. To my eye, working from home, it looks a lot like the Princeton fragment. See Versandantiquariat Christine Laist (Seeheim-Jugenheim, Germany): https://www.abebooks.com/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=30636372854&clickid=19kVAk2j9xyJRN80EWQ%3ANRupUki1rIyuNwFsTQ0&cm_mmc=aff-_-ir-_-59419-_-77797&ref=imprad59419&afn_sr=impact&utm_campaign=vialibri&utm_medium=archive&utm_source=vialibri Pricey. What do do?