Reading the Collections, Week 16: Kew Gardens

“The petals were voluminous enough to be stirred by the summer breeze,

and when they moved,

the red, blue and yellow lights passed one over the other,

staining an inch of the brown earth beneath with a spot of the most intricate colour.”

“Intricate” is probably the most appropriate word to describe Virginia Woolf’s (1882-1941) story Kew Gardens (1919), which she wrote during Summer 1917 and which is the first stand-alone publication of the Hogarth Press, which she ran together with her husband, Leonard Woolf (1880-1969) and which was partly founded to act as a therapy for her after she suffered a major breakdown. She first mentions the story in 1918 in a letter to her sister, the painter Vanessa Bell (1879-1961), asking her whether she would like to illustrate it.

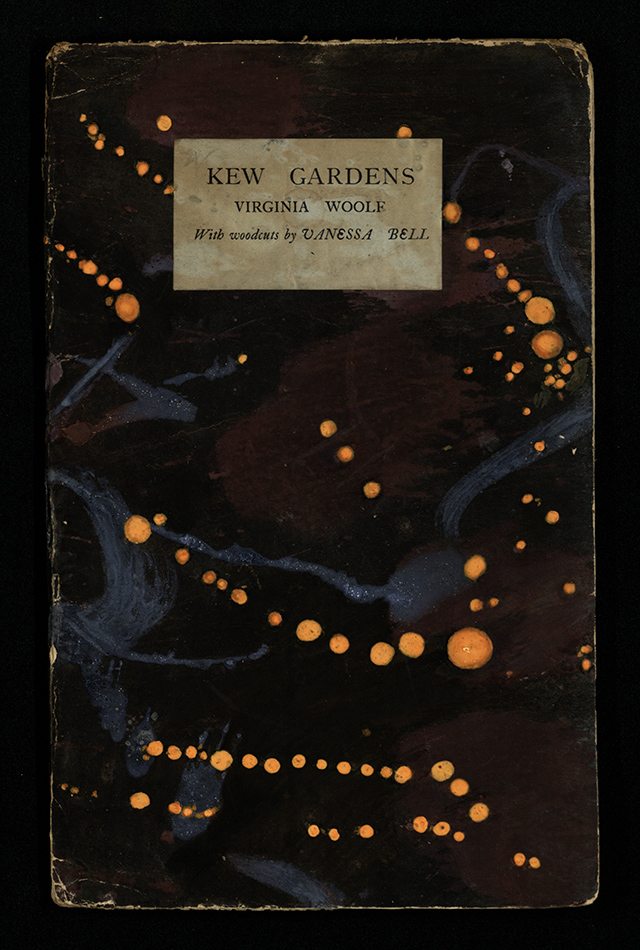

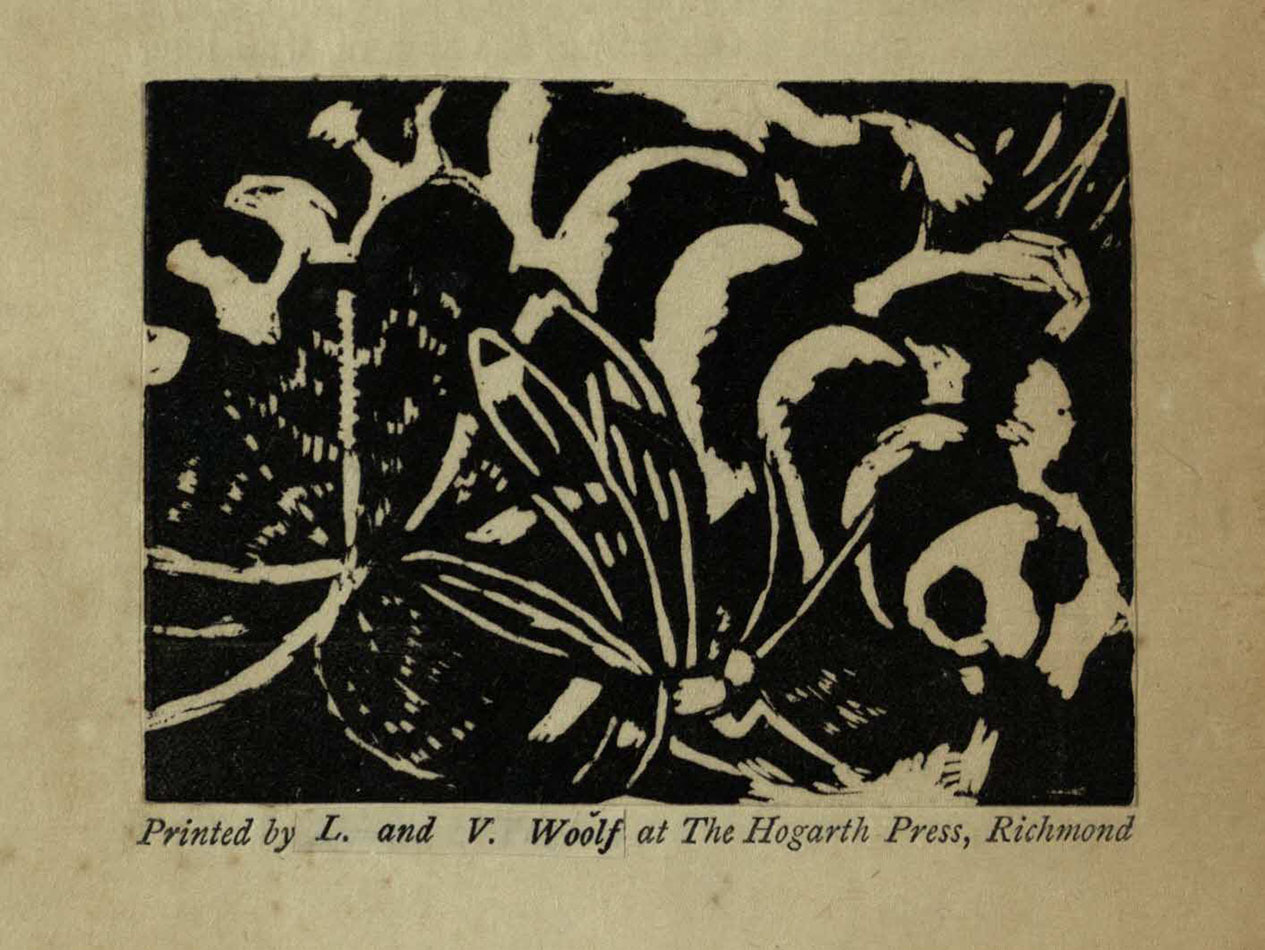

We are very fortunate to have two copies of Kew Gardens in Special Collections: one of the first edition (which was acquired in 2011) and one of the third edition (1927). The first edition is a thin, small, hand-printed pamphlet containing two woodcuts by Vanessa Bell and has a colourfully marbled cardboard cover.

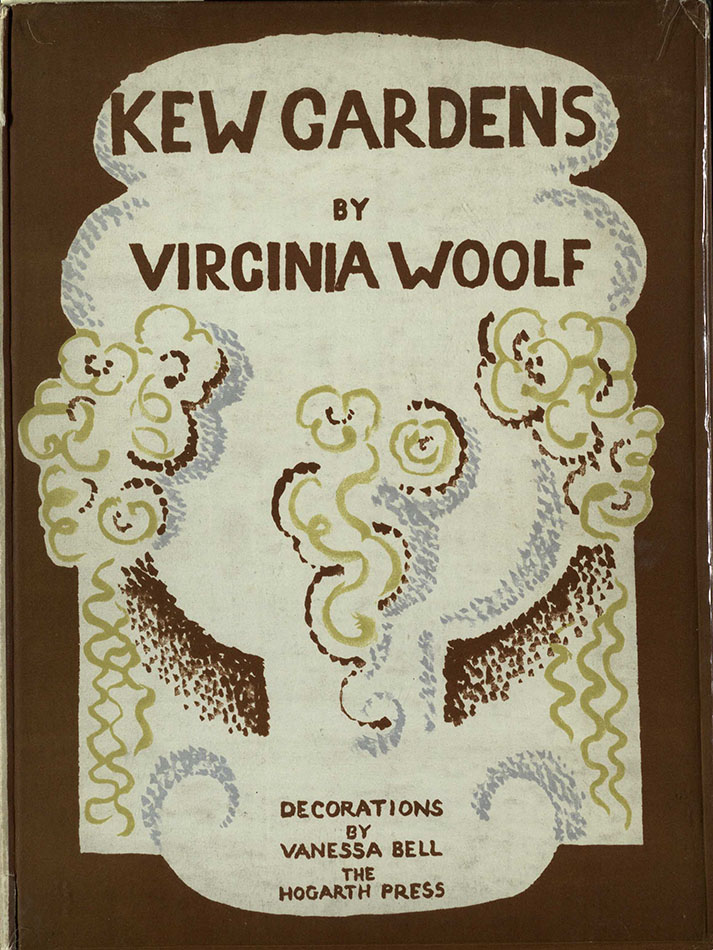

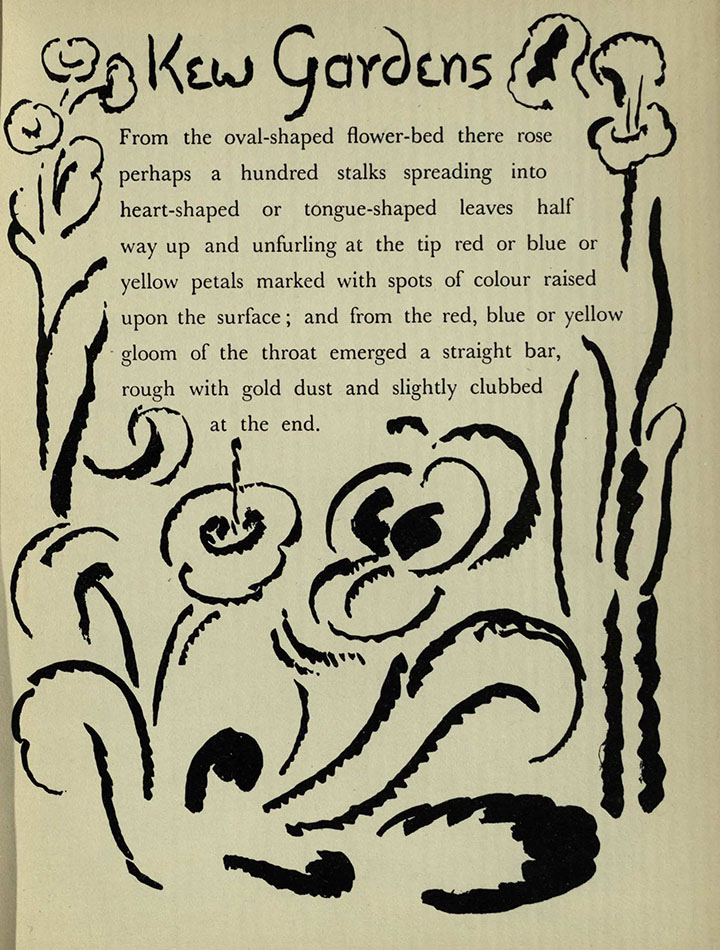

The third edition is a hardback volume with an intricate cover also designed by Vanessa Bell, who decorated each page of this volume with beautiful drawings.

In the story, we witness a hot summer day in London’s Kew Gardens: the flowers are in full bloom, butterflies are fluttering about aimlessly, a movement which is mirrored by the different people wandering through the botanical gardens. The air is ‘flimmering’ from the heat and we catch seemingly meaningless snippets of the characters’ conversations and get an insight into their thoughts as Woolf places her narrator within their minds; a narrative technique which we probably know from school as “interior monologue” and with which Woolf’s style became particularly identified.

What makes Kew Gardens so intriguing is its shifts in perspective. The focus is constantly narrowed or widened. The reader seems to look at the scenes through a camera lens which is either zooming in on details or zooming out to catch the wider picture. The story starts by focusing in on flowers in a bed, then shifts to the first couple, then goes back down to the flowerbed and a snail that is in it, then the focus opens again as the next pair of people arrive and so on. We not only follow the characters’ conversations and thoughts, but, at the same time, we follow the progress of the snail on the ground through its eyes. In the end, the story offers a panoramic view of the Gardens, where trees, plants and people blur into one another and become mere spots of colour without defined shapes.

The interaction of light, shade and colour reminded me of an Impressionist painting, almost as if Woolf had been trying to paint verbally. There seems to be an explosion of the colours red, yellow and blue when the light makes a raindrop act as a prism by breaking it up into its different component colours.

In a similar vein, the conversations we overhear are fragmented like the shards in a kaleidoscope and often very elliptical. While the snail in the flowerbed is trying to figure out whether it should go over or around a brown leaf that is in its path, four couples belonging to different social classes appear.

The first couple are married, the husband marching ahead and his wife following behind whilst keeping an eye on the children. Both are thinking of pivotal moments in their past which are linked to Kew Gardens. He thinks about an unsuccessful marriage proposal whereas she is reminiscing about a kiss she received when she was a girl during an outdoor painting class. For another couple, nostalgia for what could have been lies still in the future, as they seem to negotiate their courtship in terms of an economic exchange without overtly referring to their romantic relationship and leave their thoughts hanging in the air unsaid.

The remaining conversations reveal darker undertones, as they contain the only references to World War I. The older man in the second couple with his erratic, confused speech and jerky movements seems to display symptoms of shell shock (reminiscent of Septimus Smith in Mrs Dalloway (1925) and is obsessed with widows, the only visible reminder of all the lives lost. The “very complicated” dialogue of the two women is very similar to the collages that can be found in Between the Acts (1941) and consists of a litany of names and the frequent repetition of the word ‘sugar’, which was rationed at the time.

There is more to Kew Gardens than first meets the eye. It seems atmospheric, idyllic and even arbitrary at first sight, but is indeed a cleverly composed comment on modern life, the situation of Woolf’s contemporary society and the transitoriness or fragility of human life in general. At the end of the story, we discover that instead of being steeped in silence, the gardens resound with the sound of numerous voices and noises of the city.

The illustrations in the two different editions beautifully compliment the complexity of the narrative. The curved crayon-like lines and vaguely indicated plants or flowers framing the text in the third edition seem to convey the fleeting, vague atmosphere of the story, whereas the solid, block-like black- and whiteness of the woodcuts in the first edition seems to reflect its darker undertones very well.

Virginia Woolf herself later came to see Kew Gardens as one of the stories in which she tried out a more experimental style and which matured into a new form for the novel with her first critical success, Jacob’s Room (1922):

“Whether I’m sufficiently mistress of things – that’s the doubt; but conceive the mark on the wall, K[ew]. G[ardens]. & unwritten novel taking hands and dancing in unity.”

(Diary, 26 January 1920).

Barbara Kettel

Acquisitions