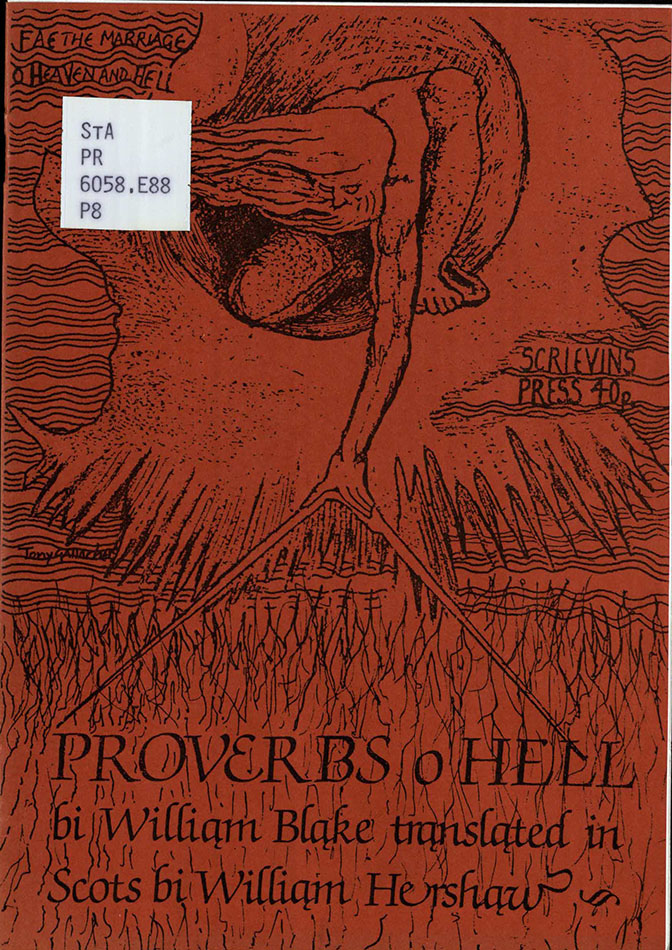

Reading the Collections, Week 24: Proverbs o Hell bi William Blake translated in Scots bi William Hershaw

This piece opens with a confession, offered by a penitent Sassenach: until very recently I thought that Robert Burns was a novelty poet, somewhat in the mould of an 18th century Spike Milligan. Sorry, I had no idea…

This state of affairs was joyfully remedied at a Burns supper soon after I moved to Scotland, where I was treated to a rendition of Tam o’ Shanter. I was smitten by the beauty of the imagery, the passionate political message and, above all, by the intensely expressive use of the Scots language. I had found a challenger to William Blake in my personal league table of poets. Like his contemporary Blake, Burns could take just a few words and express so much with them, could nuance every syllable.

So I was thrilled to find a Scots translation of Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell in the collection. The translation is taken from Scrievens, the Fife Writers Group magazine. Proverbs o Hell, Fae the Merriage o Heevin And Hell, 1793.

The background to Blake’s original work is relevant: written during the period of revolution in France and subsequent to revolution in America, the Marriage of Heaven and Hell challenges the contemporary orthodoxy in Britain which viewed purity, order and obedience as being central to civilisation. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is not a juxtaposition of good and evil (opposites), simply a juxtaposition of different outlooks. Blake would argue that the Hell he is portraying is not necessarily a bad place; simply a place where order (reason) is somewhat overshadowed by human energy and a degree of hedonism that is to be encouraged rather than admonished.

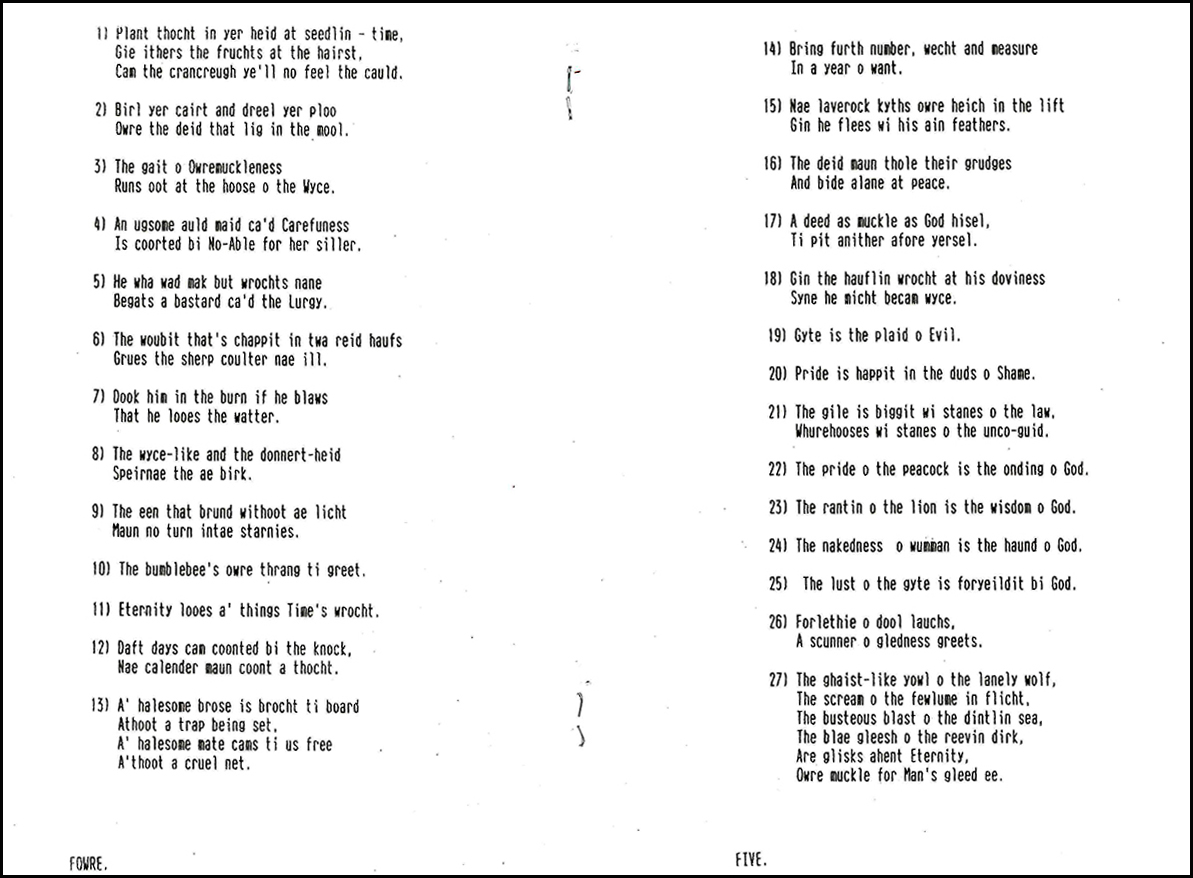

In Hershaw’s translation of two proverbs of Hell there is not too much that jumps from the page to alarm or excite: “The nakedness o wumman is the haund o God” (“The nakedness of woman is the work of God”) holds charm in the notion of God directly forming woman with his own hand – the labour being manual rather than spiritual – but otherwise the translation is very similar. “The most sublime act is to set another before you” is perhaps more interesting in translation: “A deed as muckle as God hisel, ti pit anither afore yersel.” This gives an interesting translation of sublime as being Godlike, bringing Christ’s sacrifice on the cross to the forefront as the ultimate example of setting others before yourself. But, again, the translation is pretty straightforward otherwise.

There are a few proverbs that are very much open to interpretation (as is customary for Blake in his poetic works). For example: “Dip him in the river who loves water” brings (to my mind at least) an image of the River Jordan and baptisms aplenty. Of course it might be a simple instruction to give people what they want – the hedonism alluded to earlier. In either case I am not sure that the translation gives any further interpretation or accurately reflects the original intention: “Dook him in the burn if he blaws that he looes the watter.” But then I am not a native Scots speaker – I struggle to pick up the nuances.

It becomes apparent from reading the translations that Blake’s original work is more of a political prose tract than poetry per se. Blake’s view was that some form of opposition – a world view contrary to the accepted authorities – was required in order for mankind to evolve and progress. To some extent it is disappointing that the author of the translation chose this, of all Blake’s works, to translate into Scots. Proverbs are more or less prosaic – they have an intrinsic meaning and, even if the meaning is (as here) occasionally challenging, the central message remains uncomplicated.

Reading this translation was a disquieting exercise. Translations are seldom satisfactory, however, having read Burns in Scots and in translation, original tends to bear testimony to the fact. This translation of Blake into Scots is not so blindingly obvious – the original being, by definition, a collection of single sentence homilies and thus not overly poetic. I would like to see a Scots translation of more Blake – perhaps the Songs of Innocence. If this were attempted we could see how the challenging wordplay and imagery of the mystic/romantic/radical Blake is tackled and morphed into the language of the romantic/radical Burns. But I fear that any satisfactory translation would require the genius of Burns and the collaboration of Blake to achieve it and no doubt they would be side-tracked into other works of wonder. Hmm, now that is a party that I would very much like to be invited to.

-Trevor Ledger

Golf Collections Project Cataloguer