Reading the Collections, Week 25: Shining Jewels of the East

This week we are not really reading items from the collections, but more just admiring them, and then hoping that someone out there may be able read them for us. These Burmese manuscripts of the Buddhist scripture Kammavaca, msPK4591.K2 (ms1603-1611), are written on some very beautiful lacquered palm leaves. I travelled in Burma or Myanmar back in 1999, a beautiful country full of treasures and wonderfully hospitable people, and have long admired these manuscripts. But I don’t read Pali, ancient language of Burmese monks. I’m not even sure I’ve got all these images the right way up!

Delving into the background of these leaves with the help of a couple of very useful websites, it would seem that we have a number of different sets of Kammavaca leaves, almost all incomplete, and from various times and places.

Delving into the background of these leaves with the help of a couple of very useful websites, it would seem that we have a number of different sets of Kammavaca leaves, almost all incomplete, and from various times and places.

The Kammavaca is a religious text setting out the rules and regulations that monks should live by, as well as rituals for ceremonies. It contains books from the khandaka, the second book of the Vinaya Pitaka, scriptures of the Theravadan Buddhist tradition.

The Kammavaca is a religious text setting out the rules and regulations that monks should live by, as well as rituals for ceremonies. It contains books from the khandaka, the second book of the Vinaya Pitaka, scriptures of the Theravadan Buddhist tradition.

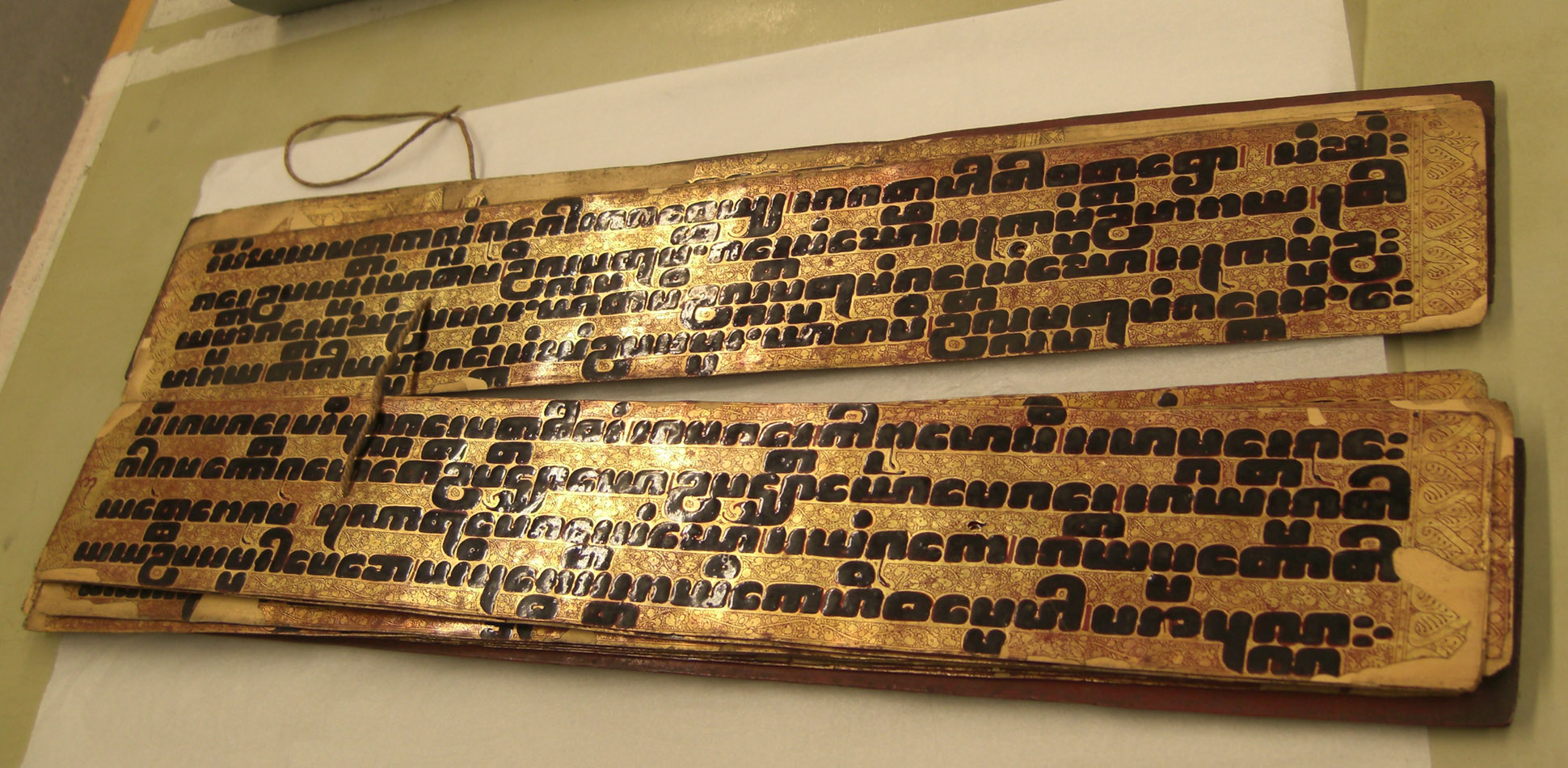

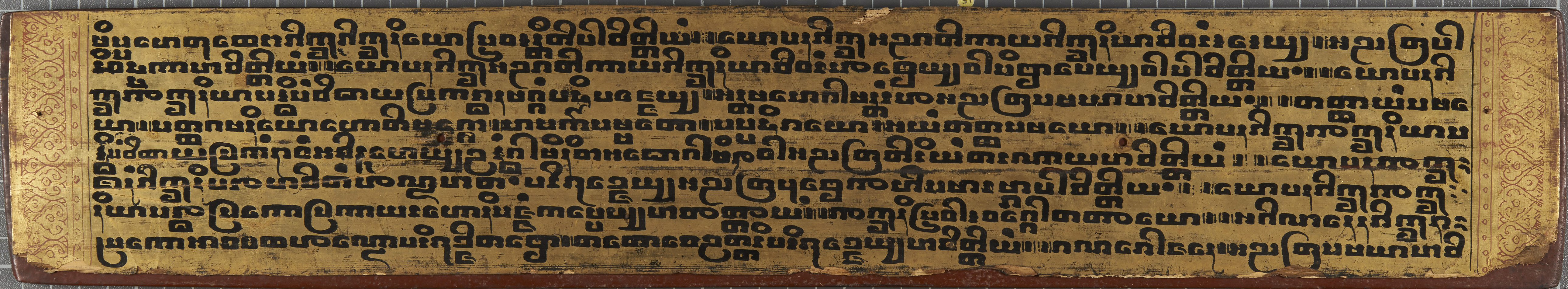

A copy would often be presented to a monastery by the parents of a boy becoming a novice or later when ordained as a monk. Traditionally made of palm leaf, then later folded cloth, the base material would be covered in lacquer, then gold leaf (shwe saing) or silver, with writing in black lacquer. The ends of each leaf are decorated with palm leaf fans and/or lotus flowers or buds. They are often a set of 16 leaves with teak outer boards (kyan) for protection, decorated with gold and red lacquer. They perhaps are joined by a string through holes in each leaf, more often loose-leaf but kept together by a wrapping of cloth with specially woven ribbon which contained a prayer (sasigyo), or in a special box made to fit. Sadly none of ours came with the cloth, ribbon or box.

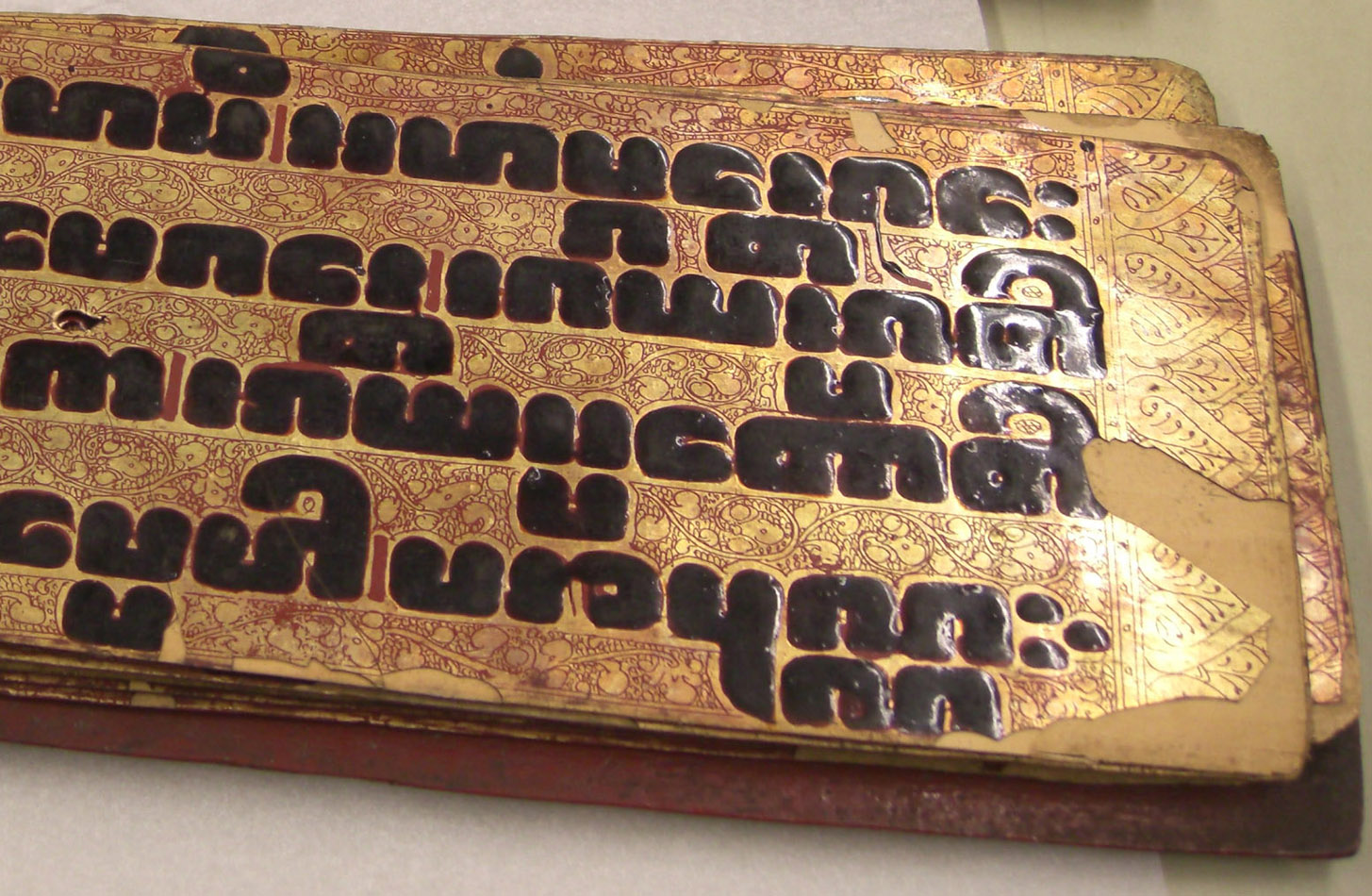

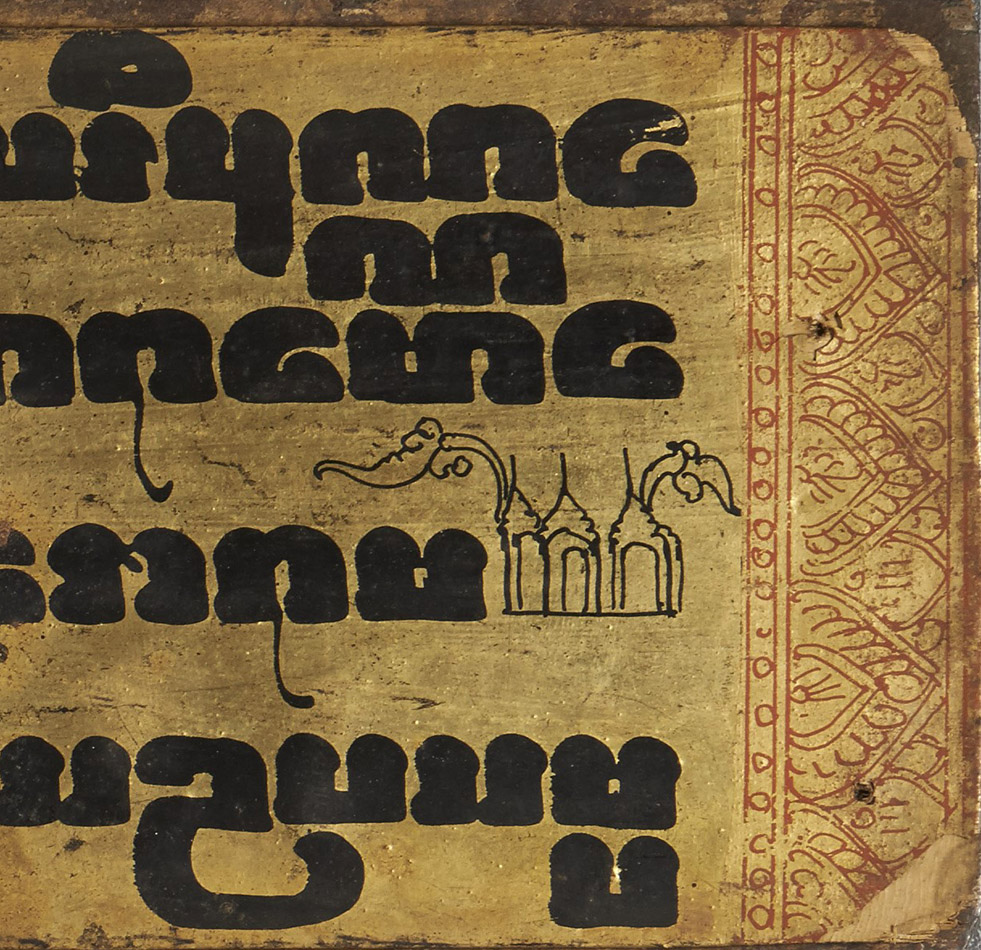

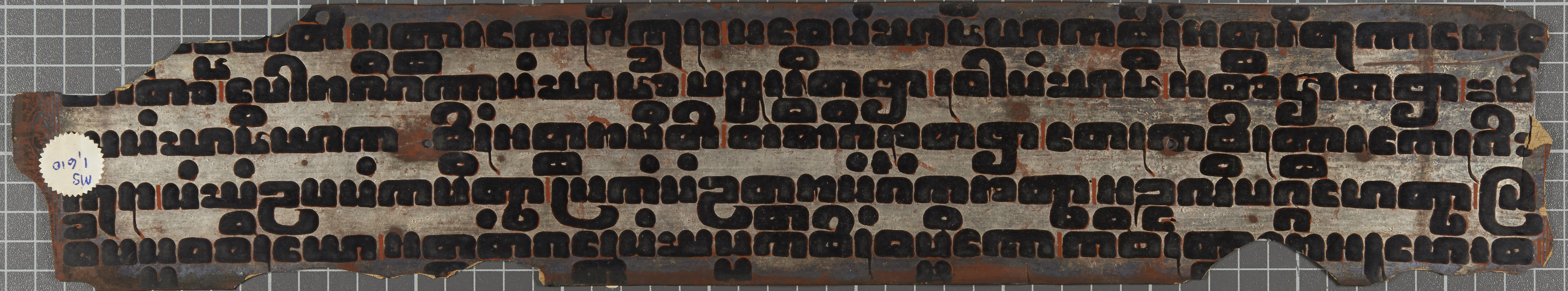

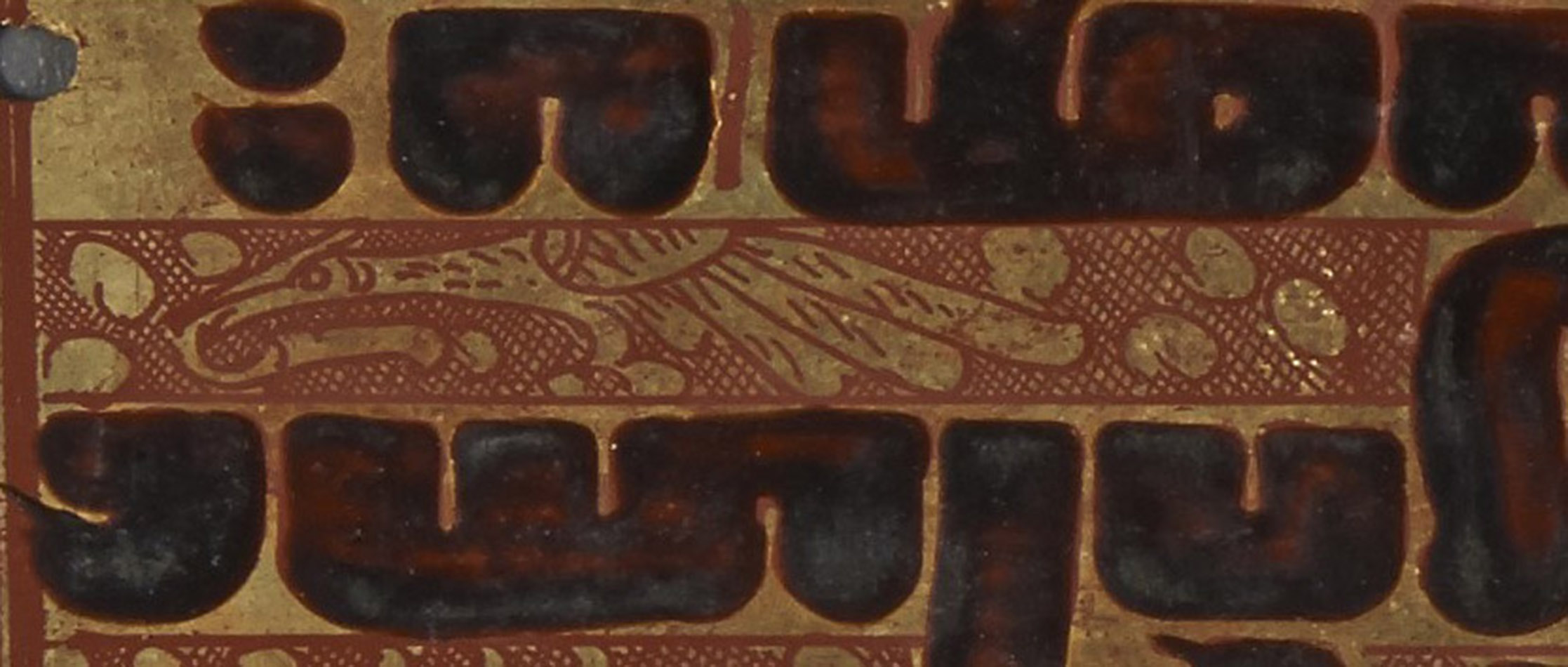

The script is distinctive, in the style of stone inscriptions. The square embossed shape made by special viscous black lacquer was thought to resemble the tamarind seed, and so it became known as tamarind seed script (magyi si sar). You can see the amazing thickness and solidity of the raised lacquer in this example:

It turns out that we have a number of sets, most of them incomplete, some just fragments. There is no information on where they came from and how long they have been in the collection, but the suggestion that they may have been ‘collected’ during one of the Anglo-Burmese wars, either 1826 or 1852, seems very plausible. Many Scottish sons were active in the military in the 18th and 19th centuries, or perhaps through mercantile activity with the East India Company, and so these were brought home and presented to the University.

Our sets are all either stunning gold or silver on palm leaf – damaged areas show the leaf underneath. The number of lines of text indicates date, in general the fewer lines, the earlier they may be.

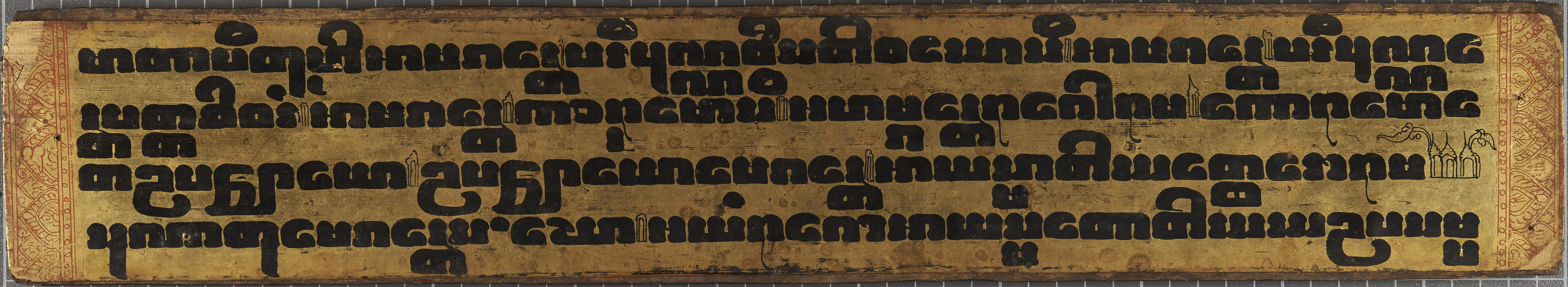

This maybe the earliest set, with 4 lines on a plain gold background, with pillars and thrones to show punctuation, which suggests a date of late 17th or early 18th c. The detail shows the end of a chapter denoted by thrones (or are they stupas?) and umbrellas.

This maybe the earliest set, with 4 lines on a plain gold background, with pillars and thrones to show punctuation, which suggests a date of late 17th or early 18th c. The detail shows the end of a chapter denoted by thrones (or are they stupas?) and umbrellas.

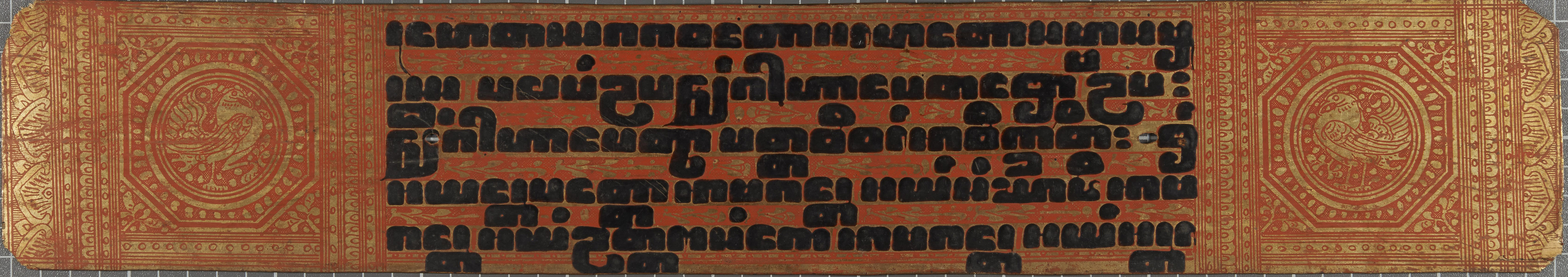

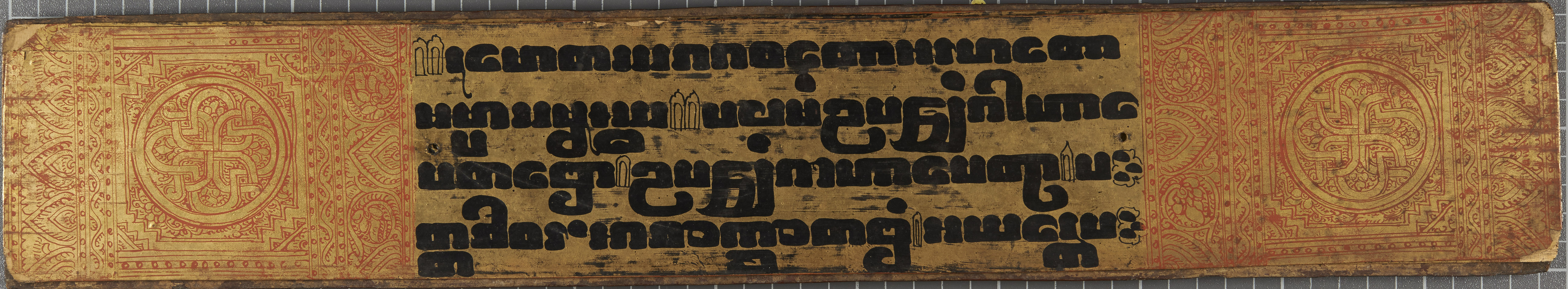

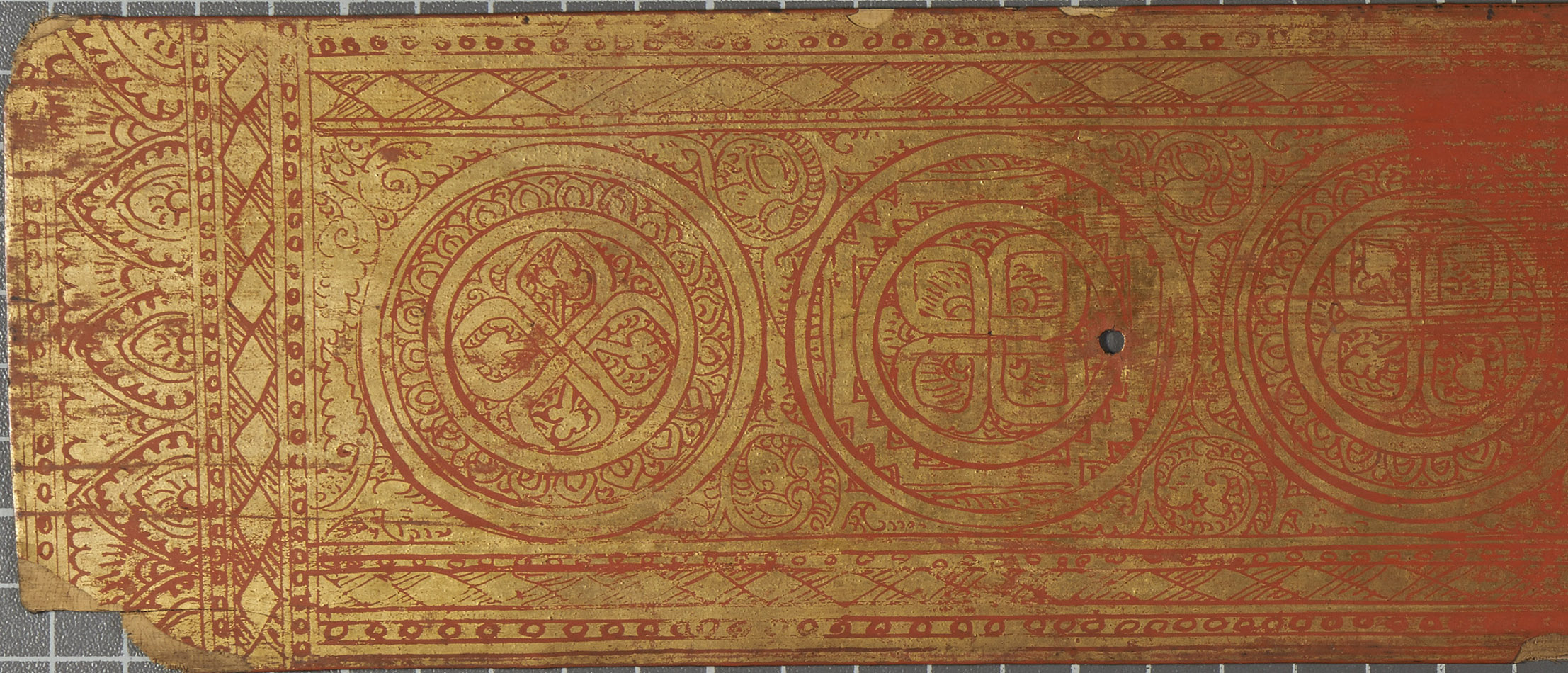

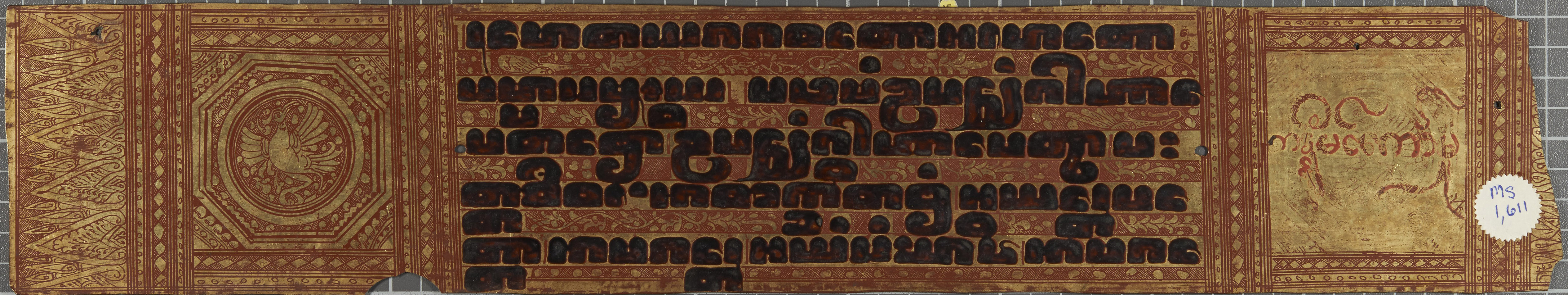

This 4 line manuscript is probably later, early to mid 18th c, because decorations between the lines have now appeared. This leaf is from the start or end of the work, with text flanked by decorated panels.

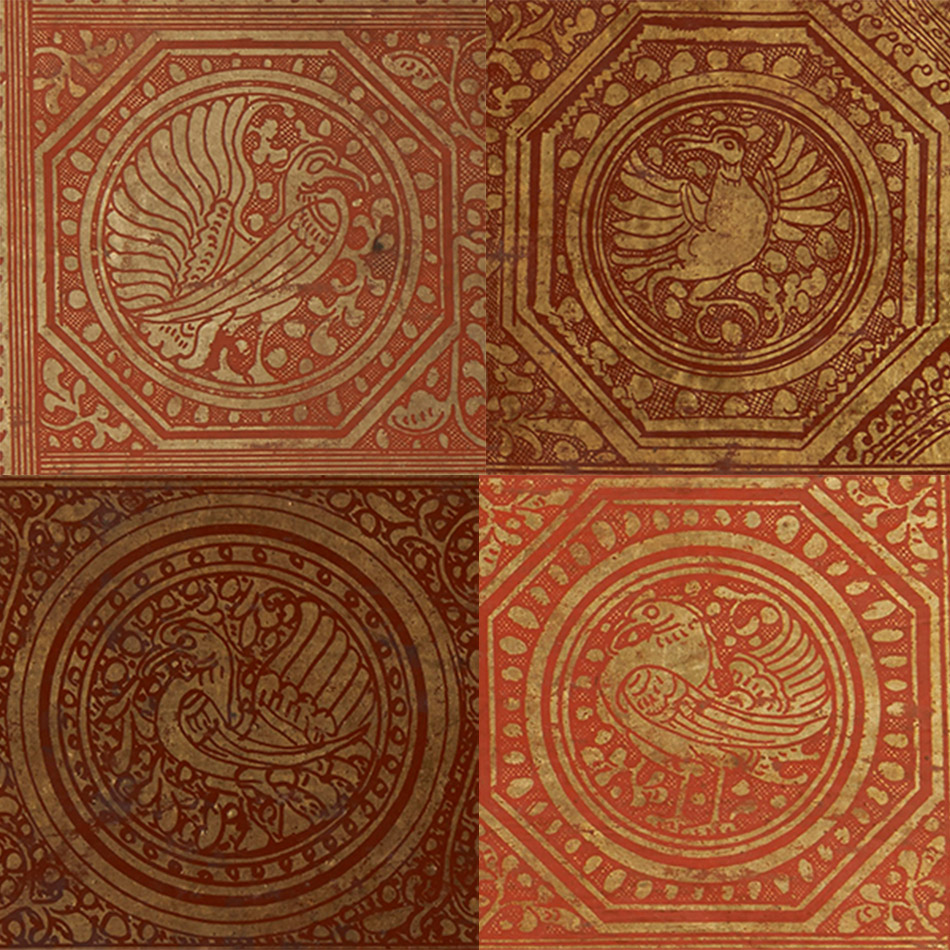

Although many decorations were used, ours are mostly of 2 kinds. Firstly birds, which may be the sacred Hintha or Hamsa bird, thought to be a kind of duck or goose, or could be the Burmese mythical bird, the karaweik.

Although many decorations were used, ours are mostly of 2 kinds. Firstly birds, which may be the sacred Hintha or Hamsa bird, thought to be a kind of duck or goose, or could be the Burmese mythical bird, the karaweik.

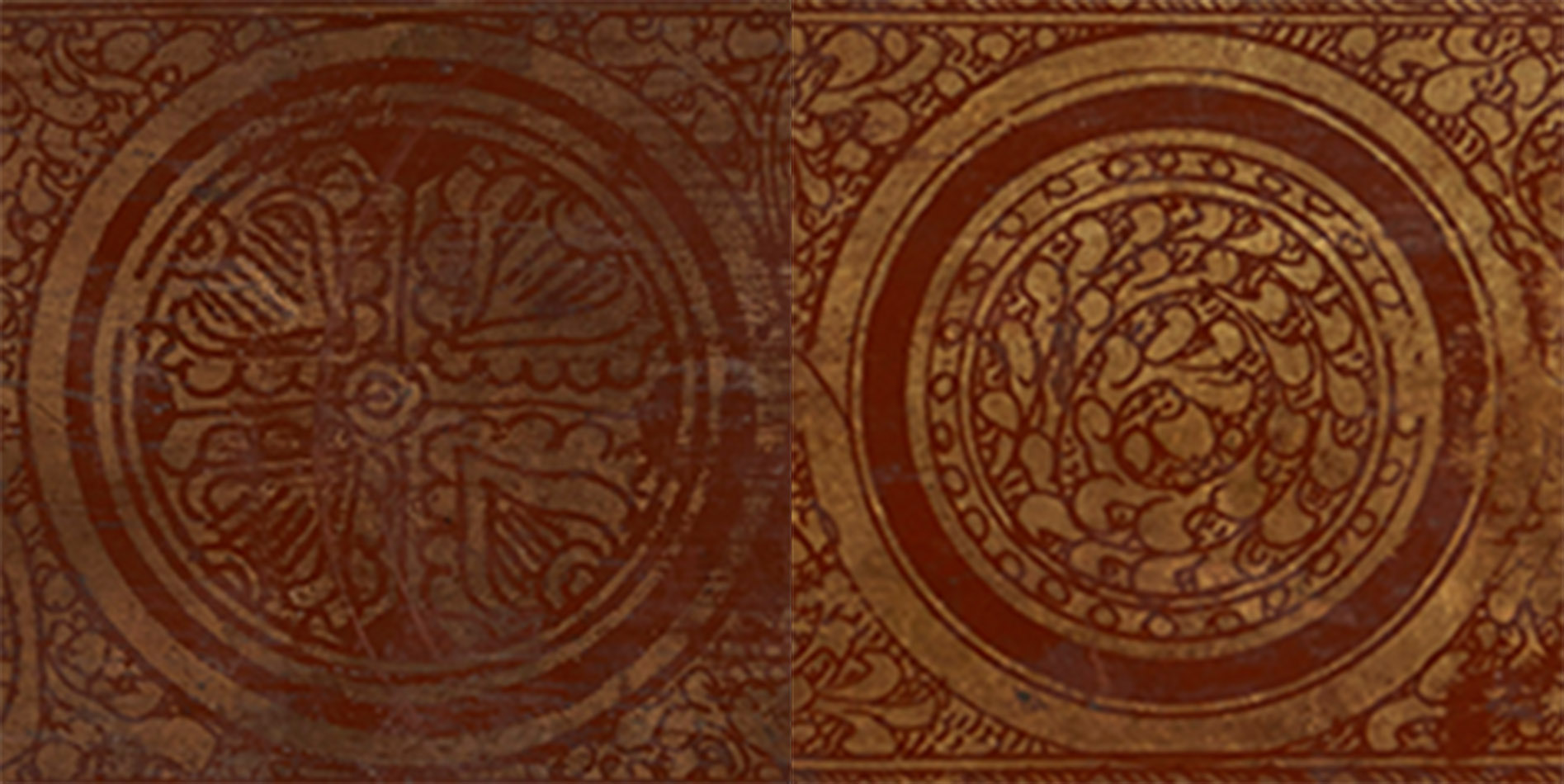

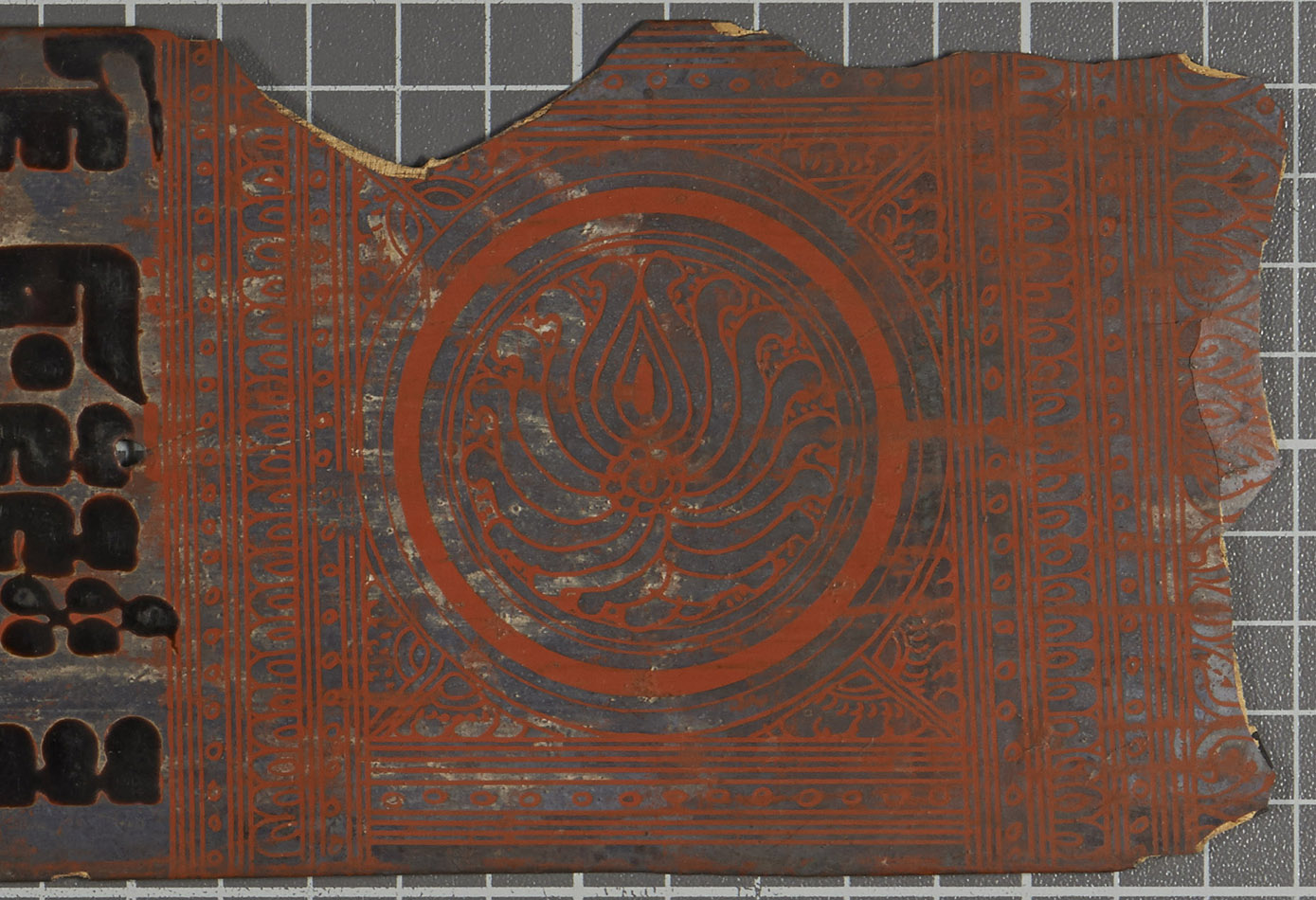

The other frequent decoration is the rosette or perhaps these are mandala, featuring knots, flowers or strings of leaves.

The other frequent decoration is the rosette or perhaps these are mandala, featuring knots, flowers or strings of leaves.

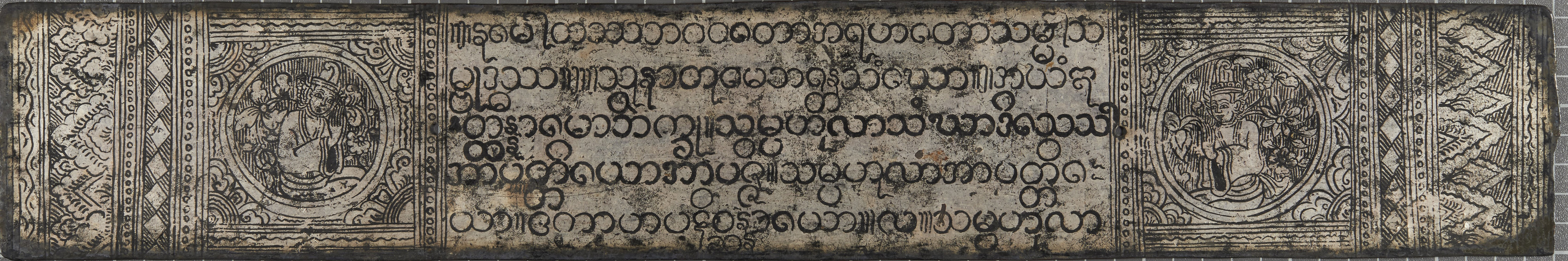

Ours don’t feature any deities as many later versions do, and only one features an image of Buddha surrounded by lotus flowers. This is an unusual set, silver instead of gold and written in round or circular script not the thick tamarind seed style. It is thought these manuscripts are associated with the Mon people of Lower Burma.

Ours don’t feature any deities as many later versions do, and only one features an image of Buddha surrounded by lotus flowers. This is an unusual set, silver instead of gold and written in round or circular script not the thick tamarind seed style. It is thought these manuscripts are associated with the Mon people of Lower Burma.

This one maybe tarnished silver, or it could be a commonly used gold/silver alloy (mo-gyo), which has faded to blackish silver over the years. It bears tamarind seed rather than circular writing, and an unusual roundel of a tear drop flower. Perhaps 18th century again?

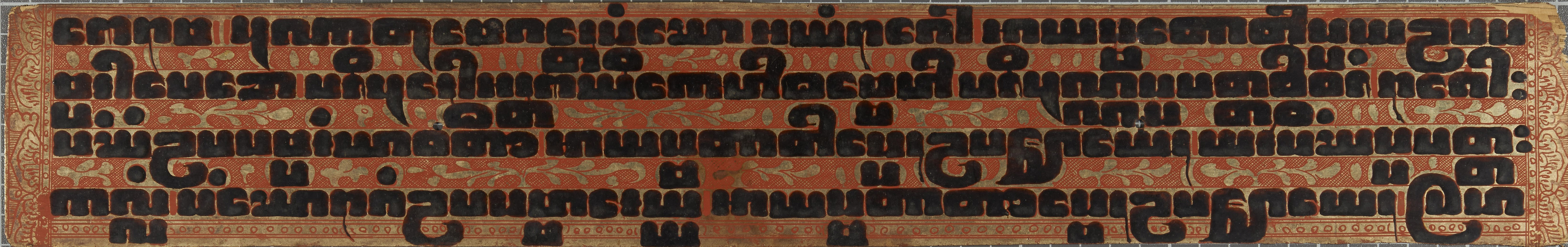

More elaborate interlinear foliate designs, often resembling mistletoe, with birds, and 5 lines of text, suggest this one is more recent, perhaps later 18th to early 19th c. The crazy dancing bird at the end is the other way up to the 2 birds hidden within the lines, giving no clues as to which way up this should be. Is that a title on the right hand end?

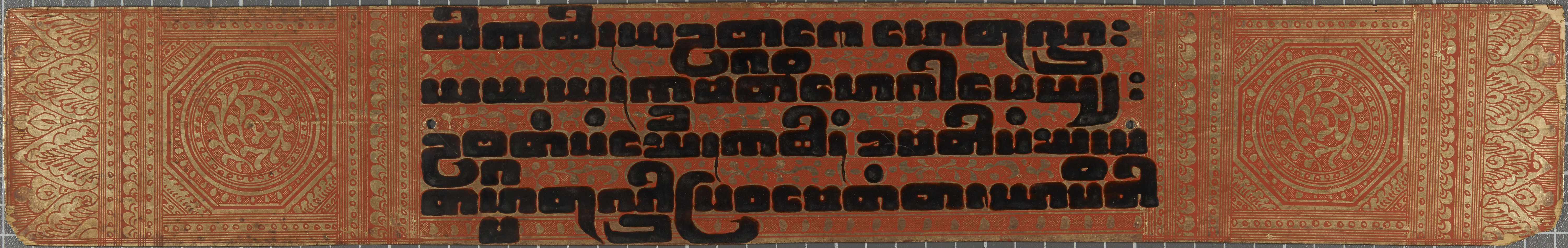

Then this one doesn’t fit as it has a plain gold background (early) but eight lines of text (late).

Then this one doesn’t fit as it has a plain gold background (early) but eight lines of text (late).

These are two very useful websites on the subject which have been used to try to work out what we have:

http://www.burmese-buddhas.com/burmese-manuscripts/kammavaca-manuscripts

http://www.gandhara.com.au/kammavaca_info.html

Even if you can’t read the script, we hope you will still appreciate the skill and craftsmanship that went into the creation of these inspiring manuscripts. We also hope to be able to add accurate details to our catalogue as a result of this post – so if you can answer any of our many questions, do get in touch!

-Maia Sheridan

Manuscripts Archivist