Reading the Collections, Week 26: Discovery of the Microbial World

Antony van Leeuwenhoek is widely recognised as the person who discovered the microbial world and I have always been intrigued by this somewhat unusual and eccentric scientific pioneer. Although he received no formal higher education, Leeuwenhoek made some of the most important discoveries in the history of biology and opened up a previously hidden world filled with weird and wonderful microscopic creatures.

The Select Works of Antony van Leeuwenhoek Containing his Microscopical Discoveries in Many of the Works of Nature (1800, translated from Dutch to English by Samuel Hoole) sQH271.L2H7 encompasses a selection of the many letters which Leeuwenhoek wrote to the Royal Society of London between 1673 and 1723 detailing his new discoveries. Our copy is also bound together with A Description of the Muscles of the Human Body as they appear on Dissection, Carpue (1801), which addresses the readership simply as ‘Gentlemen’!

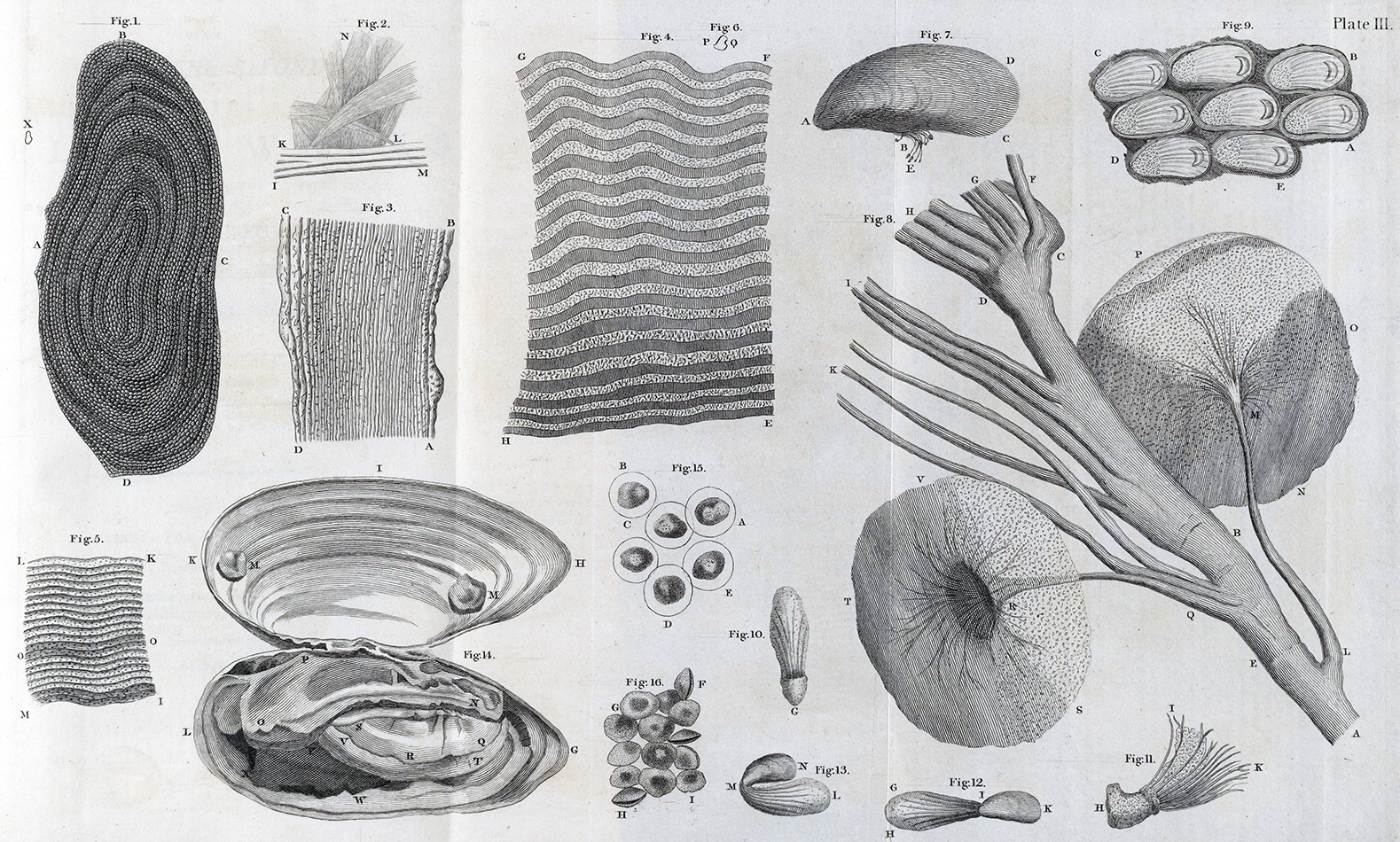

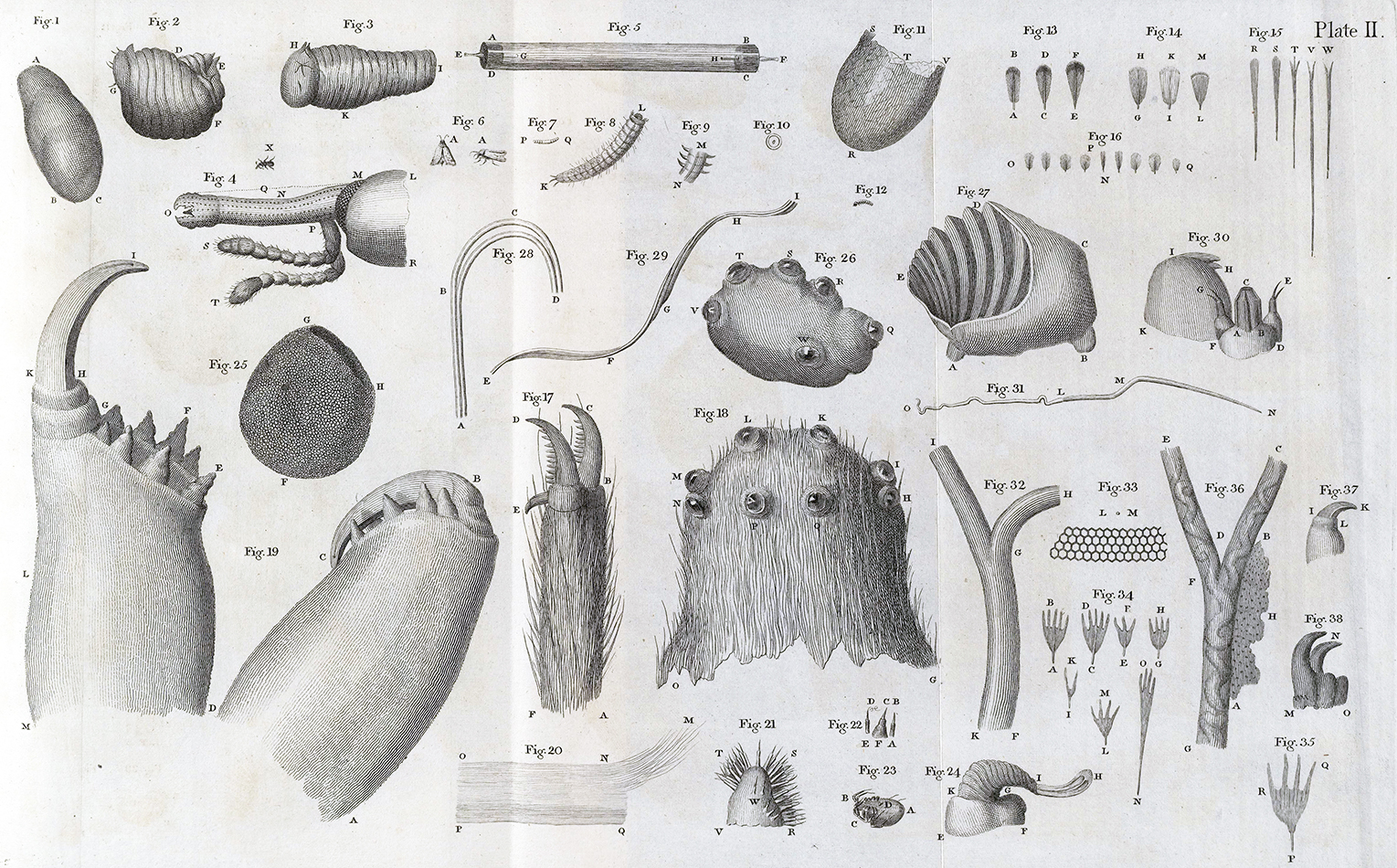

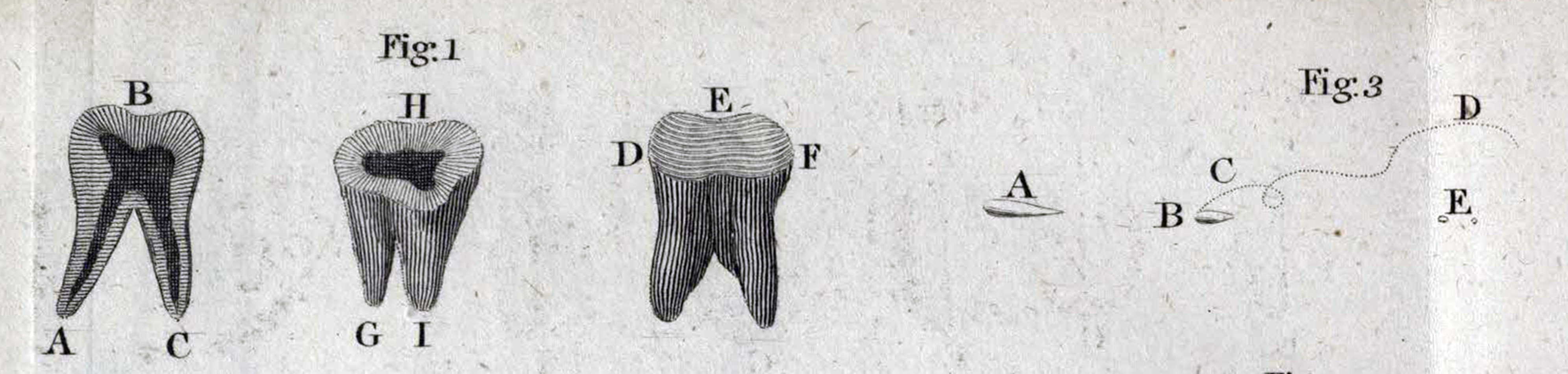

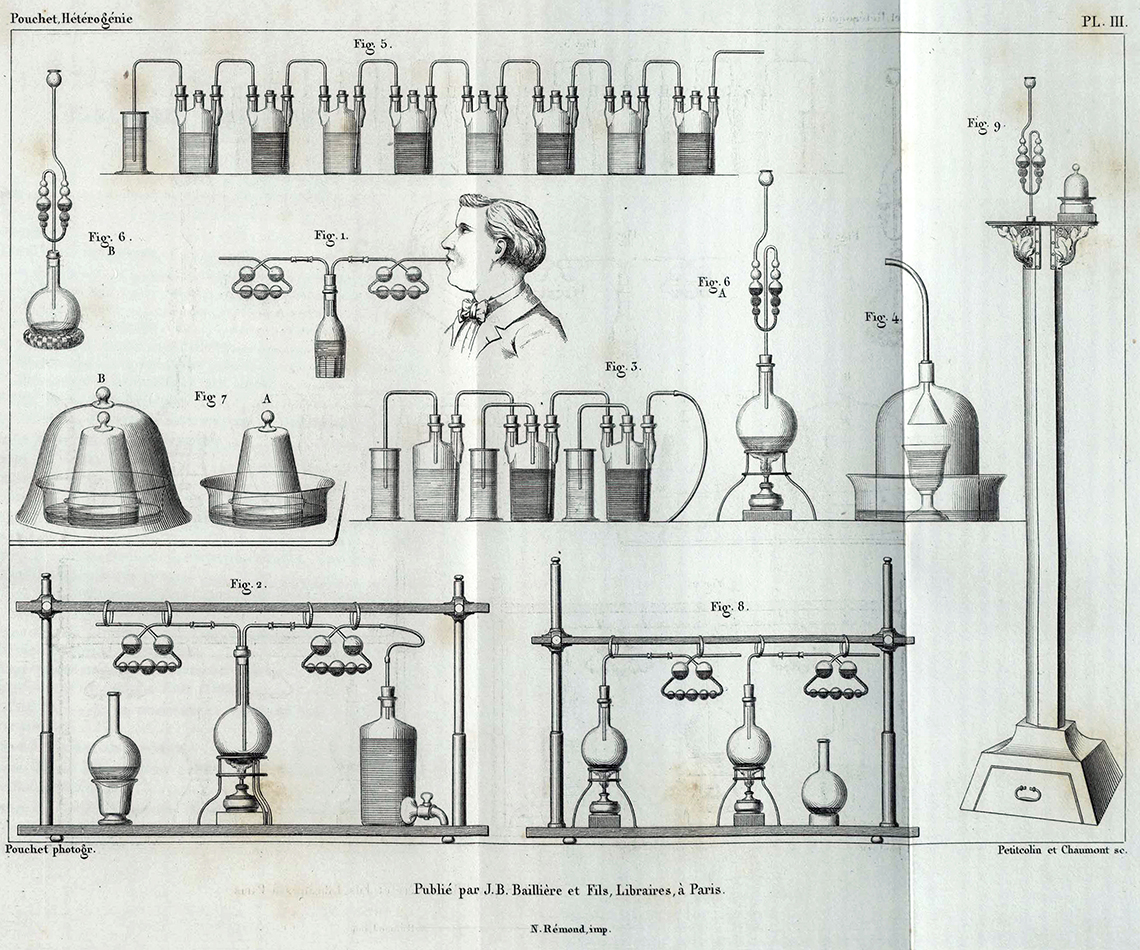

The eclectic breadth of Leeuwenhoek’s research is impressive: observations in this volume address subjects as diverse as the effects of acids in the human stomach, the nature of the sheep liver fluke and the different degrees of ‘goodness’ in fir timber. Samples gifted to Leeuwenhoek for his experiments include a whale’s eye preserved in wine from Isaac van Krimpen, the master of a Greenland-going ship and a packet from Sir Hans Sloane ‘containing three small maggots, two of which were dead, and the third alive, with a letter, informing me that they were found in a person’s decayed tooth, from whence they had been expelled by fumigation’. Leeuwenhoek developed simple single-lens microscopes to probe the structure of such samples and the resulting specimens are documented in his letters as a series of black and white engravings which exhibit a high level of detail and accuracy although no scale is included.

It is apparent that Leeuwenhoek’s life and his scientific investigations were bound up together: for him it was not mere work, more a meticulous recording of the innate joy he found in trying to understand how things work. In an experiment to observe whether it was possible to promote the growth of silkworms in the autumn Leeuwenhoek describes how some silkworm eggs were placed into a flat screwed box ‘which in the day time I carried in my pocket, and at night placed beside me in bed, that they might continually be kept warm’ and he adds that a further sample of eggs ‘my wife (who was always very warmly clad) constantly carried in her bosom’.

In another letter Leeuwenhoek describes viewing his teeth with a magnifying glass stating ‘I have observed a sort of white substance collected between them, in consistence like a mixture of flour and water’ and on further microscopic examination he records ‘that it contained many very small animalcules, the motions of which were very pleasing to behold’. This represents the first documented description of some of the microbes which are found in dental plaque.

Leeuwenhoek uses the term ‘animalcules’ meaning ‘little animals’ to describe the minute creatures he observed with his microscopes and this (now obsolete) word was adopted by other scientists and by wider society.

![A theoretical drop of water showing 16 species of ‘animalcule’ designated in the class Rotatori from Drops of Water: their Marvellous and Beautiful Inhabitants Displayed by the Microscope, Catlow (1851) sQH277.C2[SR].](https://special-collections.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2015/07/figure-6_1.jpg?w=660)

Leeuwenhoek’s writings also reveal a deeply religious man. It appears that the more he discovered about the beauty and method of nature, the more he was sure of a heavenly creator at work. ‘When we duly consider this most perfect workmanship of the Divine Artist, we must confess, that those things which we discover by our microscopes and industry, are but as the shadow of those which hitherto remain concealed from us.’

Lindsey Gray

Golf Collections Digitisation Officer

Great article...staggering stuff cf Robert Hooke. HOWEVER when introducing someone not generally 'known' you should give dates of birth/death and country of origin - it is very confusing to read dates of publication with no context as to the date of his work. The only key to his life span was in reference to his letters to the Royal Society.

Thanks for your comment Liz. Further information about Leeuwenhoek is present in the embedded hyperlink. Micrographia is thought to have been a major source of inspiration for Leeuwenhoek's work.