Where we find new old books, chapter 3: buried treasure amongst the stacks

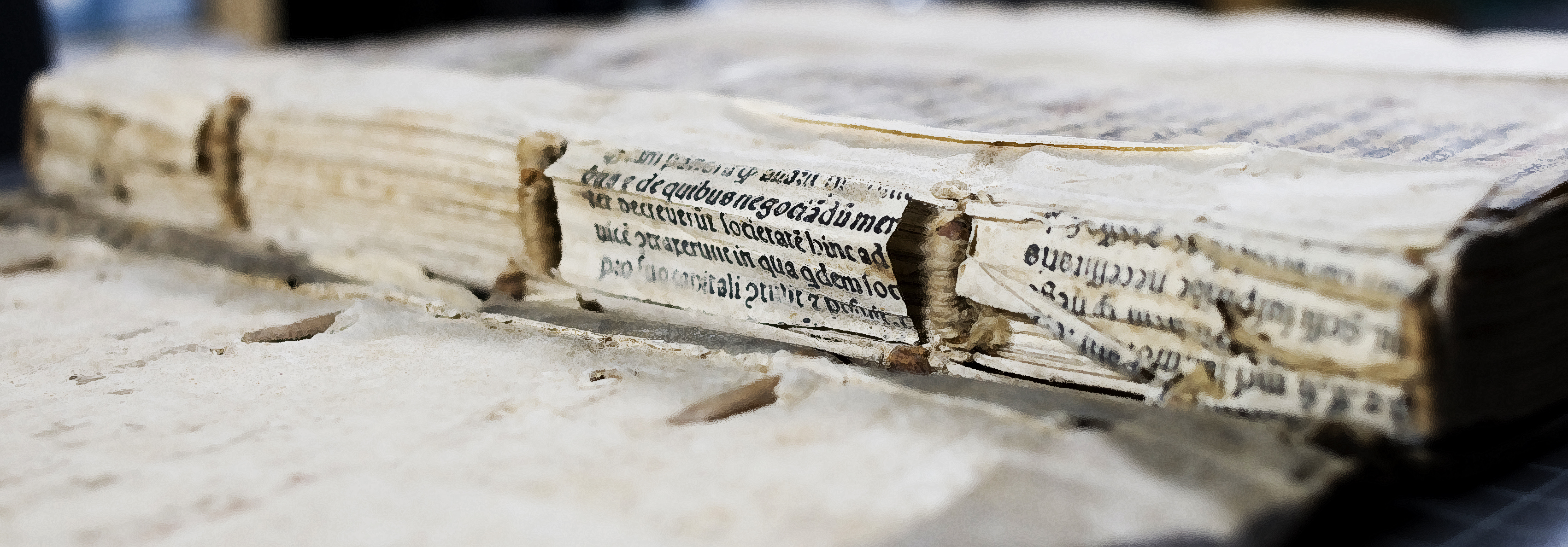

This is what buried treasure looks like in a library:

This book, which is a collection of two perfectly respectable but not very rare tracts by Vatican Librarian Agostino Steuco, has acted as a vessel, a treasure chest, for the bits and pieces that went into the binding and physical construction of this book. This volume has come off the shelf recently during some scans of the stacks and, although quite rough looking from the outside, when we opened it up a whole process of discovery began. The manuscript leaf that was used to wrap and cover this book, and why it was washed black, was of interest and was what initially had caught our eye in the stacks; however, as we opened the volume we were thrilled to find a much earlier manuscript fragment tied into the binding, and, because the book is in such a poor state of conservation, the spine and the printed waste fragments used as spine-guards, were exposed. This was all a surprise, mostly because until very recently the catalogue record for this book plainly described the binding as “bound in a piece of vellum Latin MS, further fragments in binding, traces of ties”. That was it.

In fact, almost everything about this book hints at the economy, the recycling nature of the book world in early modern Europe:

The boards used for the front and back cover of the book show every sign of being taken from another, similar sized book, and being reused for this book (we can tell this from the extant lace-holes seen in the board);

Because of the state of preservation of this book (read: dire), the spine was fully exposed and the waste material commonly used to pack a spine cavity or protect the gatherings from the cover rubbing at the spine was in plain sight;

And two leaves, both fragmentary, of the same late 12th century manuscript have been sewn into the front and back of the book (these leaves, and the outer wrapper have now been assigned St Andrews manuscript numbers: ms38983/1-3). The front and back of the book are not uncommon places to find manuscript waste; however, normally this waste is used to wrap around and protect the first and last gatherings of a book. In the case of TypFL.B47GS, though, the fragments of the manuscript have simply been laced into the structure of the book, almost as if the owner of the fragments had sewn them into his book for safe-keeping.

Rachel, our resident palaeographer, got rather excited by these fragments (the understatement of the week) and has spent her spare time of the last few days closely examining the text and the hand. Here’s what she has to say:

“Each fragment contains 33 lines of text, one column on each side, so we have 132 lines in all. There is some damage, particularly along the outer edges and at the folds and in one column a line has been erased and written out in abbreviated form in the top margin but never copied back into the text block. The leaves seem likely to have come from a breviary. They include liturgical material for the offices for ferial 2 and ferial 3 in the Octaves of Easter (i.e. Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday). The litany contains antiphons, versicles, responses, and prayers, along with short Bible and lectio readings, from the 23rd Homily of Pope Gregory, and Luke chapter 24. This covers part of the resurrection narrative and the appearance of Jesus to disciples on the road to Emmaus. The text frequently refers to Vespers. Ordinary liturgical texts like these were in constant use, regularly became obsolescent and were subject to the effect of religious reformation and most survive in bookbindings (read more on this in Christopher de Hamel’s History of Illuminated Manuscripts) – so perhaps we should not have been surprised to find them in this book!

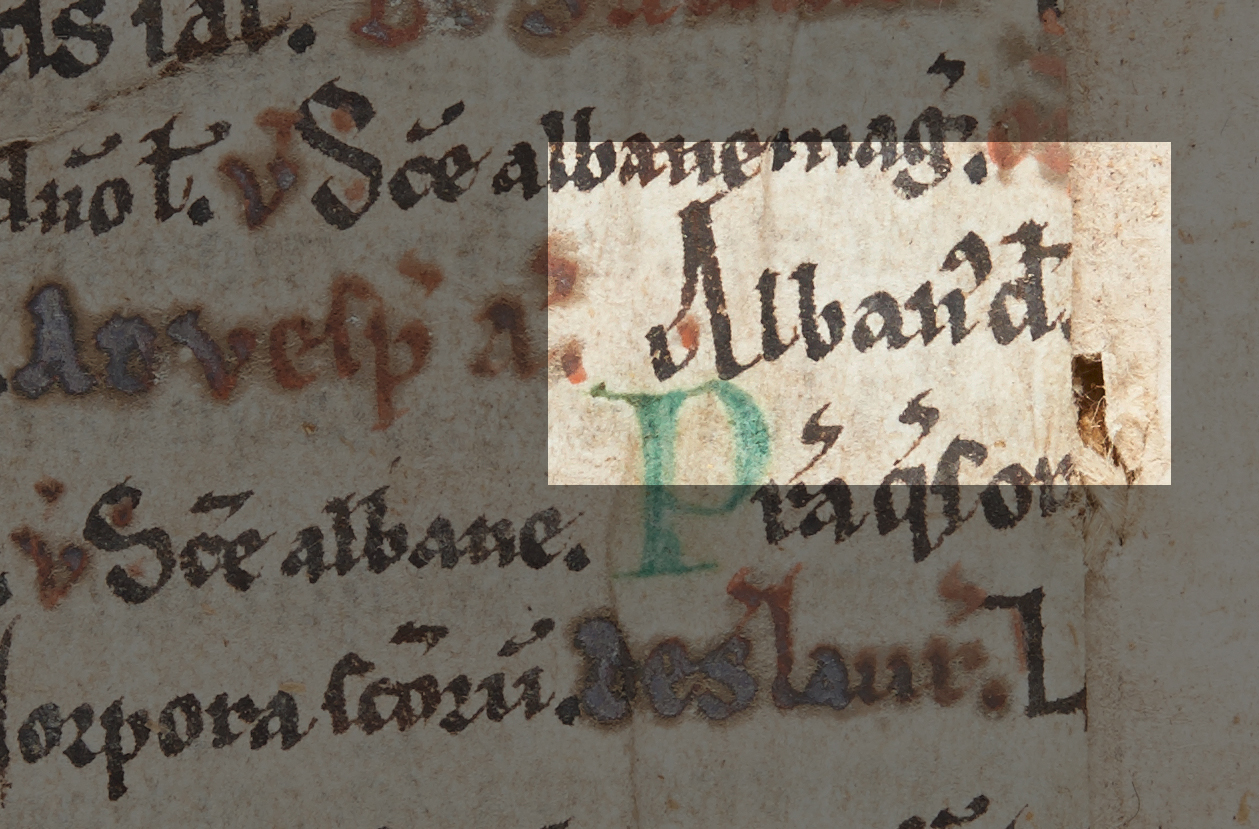

“The script is a clear protogothic hand, with two variants, one more formal and square used for the prayers in the office, and a smaller more informal and more pointed style for the versicles and responses. There are red and green initials and red rubrication, some of which is in rustic capitals. On occasion the red ink shows evidence of having been overwritten with silver, oxidised deposits [1] of which remain on the page. An analysis of the hand indicates that the text dates from the later part of the 12th century. Particular features such as the use of y (ymnus) [2] and treatment of the abbreviated forms of Praesta quesimus and populum (Cappelli) [3] as well as the wavy contraction line [4] and the separation of letters such as ‘pp’, and ‘the occasional biting in letter pairs with contrary curved strokes (do) [5]’ (de Hamel, p.94 and e-mail correspondence from Erik Kwakkel, University of Leiden) suggest a date of circa 1175. Erik also adds that the ‘decoration style in for example A and D at f. 2v points at second half of 12th century’.

“The script is a clear protogothic hand, with two variants, one more formal and square used for the prayers in the office, and a smaller more informal and more pointed style for the versicles and responses. There are red and green initials and red rubrication, some of which is in rustic capitals. On occasion the red ink shows evidence of having been overwritten with silver, oxidised deposits [1] of which remain on the page. An analysis of the hand indicates that the text dates from the later part of the 12th century. Particular features such as the use of y (ymnus) [2] and treatment of the abbreviated forms of Praesta quesimus and populum (Cappelli) [3] as well as the wavy contraction line [4] and the separation of letters such as ‘pp’, and ‘the occasional biting in letter pairs with contrary curved strokes (do) [5]’ (de Hamel, p.94 and e-mail correspondence from Erik Kwakkel, University of Leiden) suggest a date of circa 1175. Erik also adds that the ‘decoration style in for example A and D at f. 2v points at second half of 12th century’.

“The fragments are of English origin. This is evidenced by the presence of English saints in the memorials or suffrages of saints (Alban [see left], Cuthbert and Oswin for example). The hand is consistent with documents of known English origin, and letter forms such as the pointed capital of Albanus show typical English features. Erik pointed out that the text contains chants that are recorded in the Cantus database: – Quo agnito discipuli in Galilaea propere pergunt videre faciem desideratam domini (386837); Ostensa sibi vulnera in (008271i); and Qui sunt hi sermones quos (377958). These three are hymns of the Anglo-Saxon Church, known from the Durham Hymnal (Durham Cathedral Library ms B.III.32). Much more could be said, but since we hope to use these in palaeography teaching, we can’t give away all the details or there will be no chance to set them as transcription/research exercises!”

“The fragments are of English origin. This is evidenced by the presence of English saints in the memorials or suffrages of saints (Alban [see left], Cuthbert and Oswin for example). The hand is consistent with documents of known English origin, and letter forms such as the pointed capital of Albanus show typical English features. Erik pointed out that the text contains chants that are recorded in the Cantus database: – Quo agnito discipuli in Galilaea propere pergunt videre faciem desideratam domini (386837); Ostensa sibi vulnera in (008271i); and Qui sunt hi sermones quos (377958). These three are hymns of the Anglo-Saxon Church, known from the Durham Hymnal (Durham Cathedral Library ms B.III.32). Much more could be said, but since we hope to use these in palaeography teaching, we can’t give away all the details or there will be no chance to set them as transcription/research exercises!”

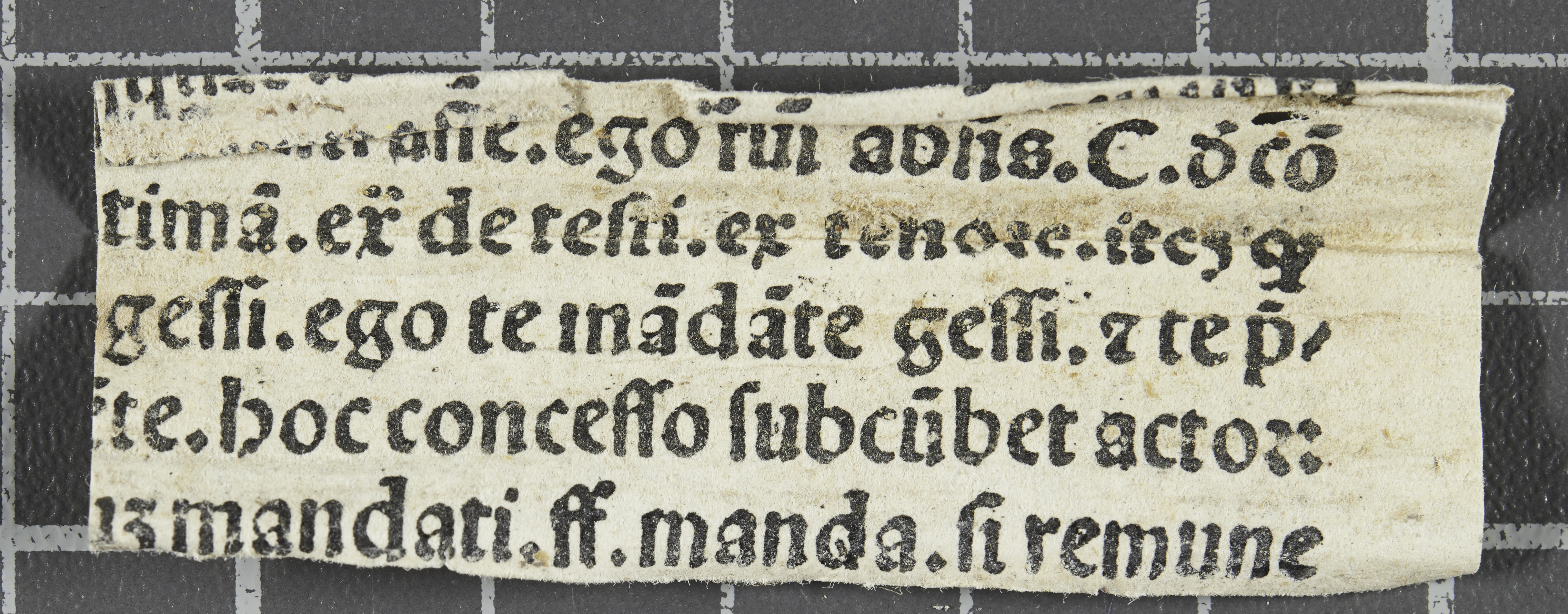

The bits of printed waste used as spine-guards were also of particular interest. By comparing the size and type of typography, the two visible fragments (one of which had become detached) both looked to be from the same work, and both looked quite early – maybe even 15th century early. However, with each fragment measuring just slightly over 50x20mm, displaying at most five lines of type, we had little to go on. So, just like the previous blog post in this series, we reached out to our friends Dr Falk Eisermann and Dr Oliver Duntze at Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW) in Berlin for a little help. I sent them this image (which is to say, very little to go on):

Amazingly, incredibly, within two hours Oliver, emailed back, quite casually, the following:

“Look here: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00052570/image_46

Second column, line 15 from the bottom.

That’s GW 09161 Duranti, Guillelmus: Speculum iudiciale. Venice: Baptista de Tortis, 1499.”

We then identified that the other fragment, still attached to the spine, comes from the same page, just slightly higher up in the same column. The mechanics of just exactly how Oliver was able to make this identification based on such little evidence is still unclear to us, he’s clearly operating on an enlightened bibliographical level that can only be obtained by staring day-in and day-out at 15th century typography. Whatever the case, according to ISTC these very fragmentary witnesses to this 1499 imprint found in our binding are now the second copy of this work to be recorded in the United Kingdom.

∴

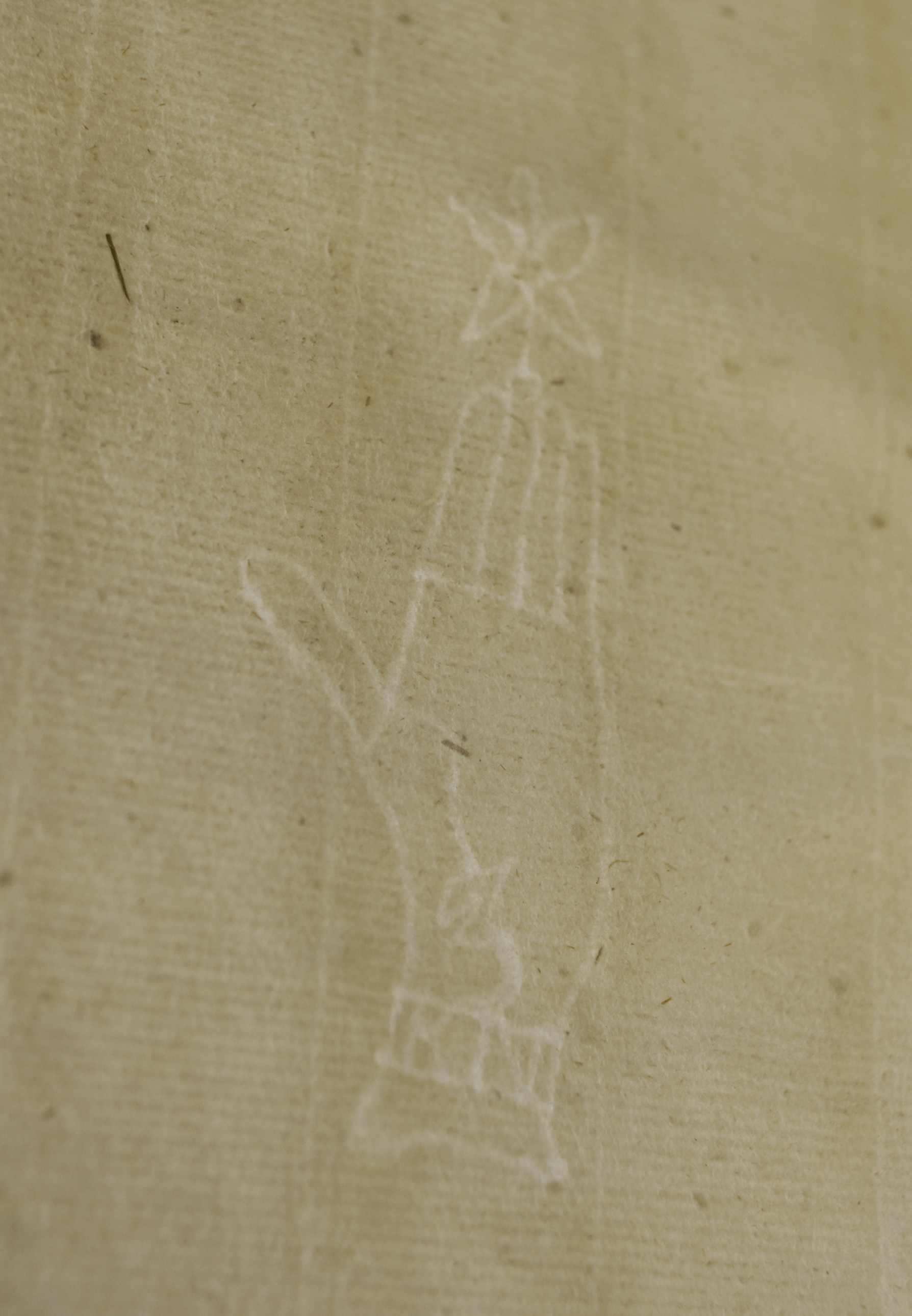

So, when did all of this get chucked into this binding? Well, it’s quite hard to tell; it is well known that both manuscript and printed waste was regularly circulated to binders, dress-makers, etc. The only bit of evidence that has helped us potentially locate and date the construction of this binding has been the watermarks found on two of the added fly-leaves:

This watermark is a near-match to C.M. Briquet’s 11380 or 11381, but not exact. Both watermarks are dated 1552 by Briquet and identified as paper used in Osnabrück, Bruges and Clervaux. So, we can be fairly certain that this binding came together sometime in the 1550s in the north of Europe.

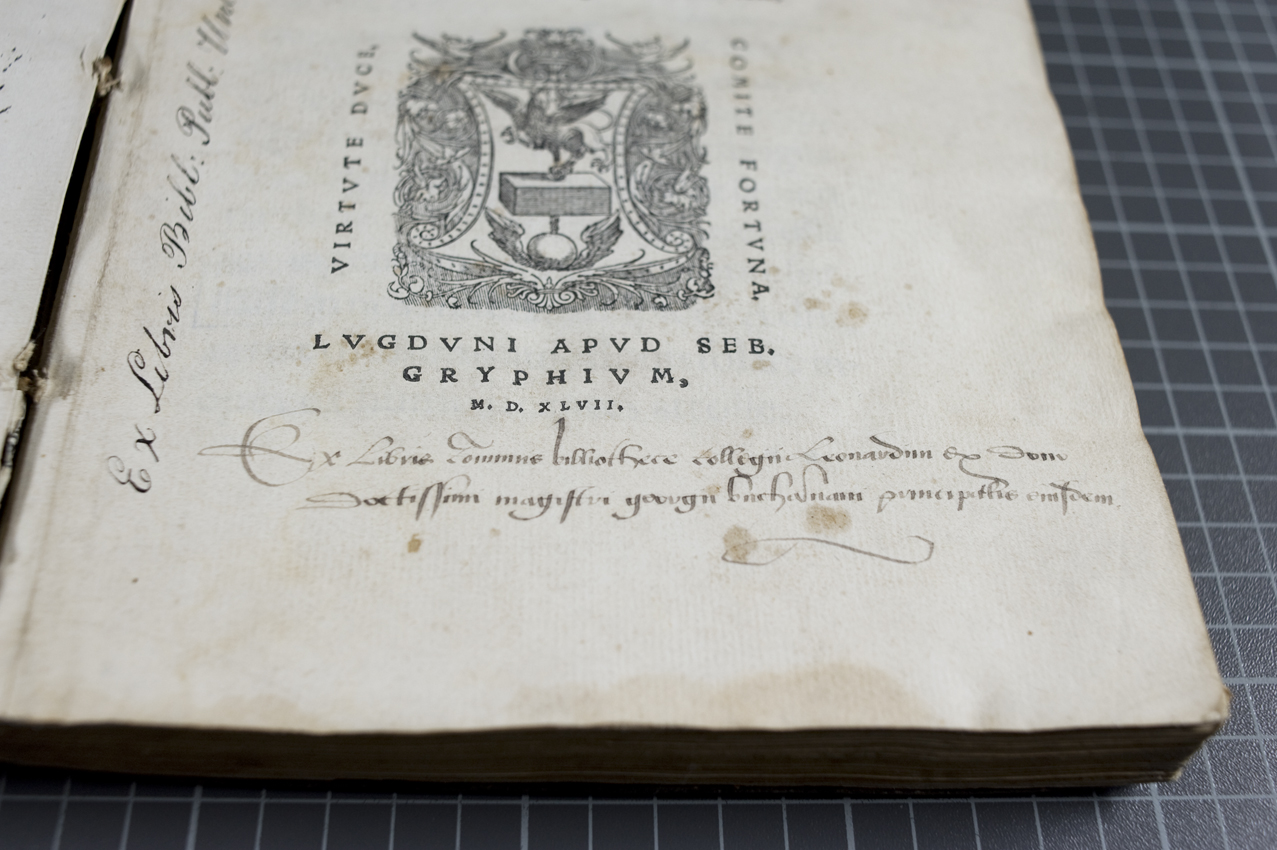

We do know that this book was one of many donated to St Leonard’s College in the 1570s by George Buchanan; this certainty is taken from the presentation inscription (left) which is found at the foot of the title page of the first item in the volume and which is repeated at the back of the book.

So, in conclusion, we have a couple of books that were written by an Italian librarian, printed by a German working in Lyon in the second quarter of the 16th century; these books were bound together, probably in the north of Europe, in the 1550s in a leaf of a 15th century manuscript Bible, using printed waste originating from 1490s Venice and the cuttings of a leaf of a 12th century liturgical manuscript as packing and support for the structure of the book. This book was then acquired by the Scottish humanist George Buchanan, and was on shelves in remote St Andrews by the last quarter of the 16th century. Pretty much a canned history of the book trade in the 16th century all in one book!

–DG & RH

N.B. A huge thanks to those that have helped us in identifying and processing the new items uncovered in the book: Dr. Erik Kwakkel (Leiden); Dr Falk Eisermann and Dr Oliver Duntze (Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke); and Jamie Cumby, our MEI Intern, who put together the catalogue record for the new incunabula fragments.

N.B. 2 – This book will soon be going off to conservation, and so hopefully this book’s current dire state will be remedied!

Fascinating detail! (And I'm looking forward to starting my research project investigating your Music Copyright collection in just a couple of weeks, so I look forward to meeting some of the team again in due course ... lovely books, lovely people ...)

Stuff for a Hollywood blockbuster, Daryl! "And the Oscar goes to ... Oliver Duntze for 'The Men Who Stare at Types'". Keep, on the good work, cheers, Falk

Thanks, Falk, and thanks to your team again for such sterling work. Perhaps someday a film will be made about the GW team - I can just see the headlines now: "a rag-tag team of the world's best book historians assembled to answer the book history world's most niche of questions!" Kind of like Armageddon, but with books instead of meteors!

[…] Buried Treasure Amongst the Stacks: “a canned history of the book trade in the 16th century all in one book!” […]

[…] The University of St. Andrews is finding buried treasures amongst their rare book library stacks. […]

[…] Using incunabula catalogues is often tricky and requires special knowledge. In many cases catalogues are accessible only in foreign languages. The leading bibliographical authority, the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (which we’ve been informed is celebrating its 111th birthday tomorrow!) can only partly be accessed in English. Throughout the workshop the students developed a sound understanding of terminology and how they can describe incunabula. Bibliographic information on the first printed books is abundant, but finding a specific copy can be difficult. Eisermann explained in detail how catalogues such as the GW, BMC and Hain can help to find information on early printed books. He also introduced students to more specific catalogues; sources of particular use when trying to identify fragments. Together, the group worked through how a tiny fragment found in the binder’s waste of a sixteenth century French book was identified. […]