Reading the Collections, Week 33: It’s all Greek to me

Cataloguing the backlog of early and rare printed books held in the Special Collections Division of the University Library can be a source of surprises. We have to admit, the majority of the books we work with are not very exciting to catalogue, either because of the date, the printing, the subject, or even the language. And yet, often, hidden between a series of not-so-interesting books, appears a little treasure, a 16th century gem that has been hidden away all this time behind a line of younger, better-looking-on-the-outside books.

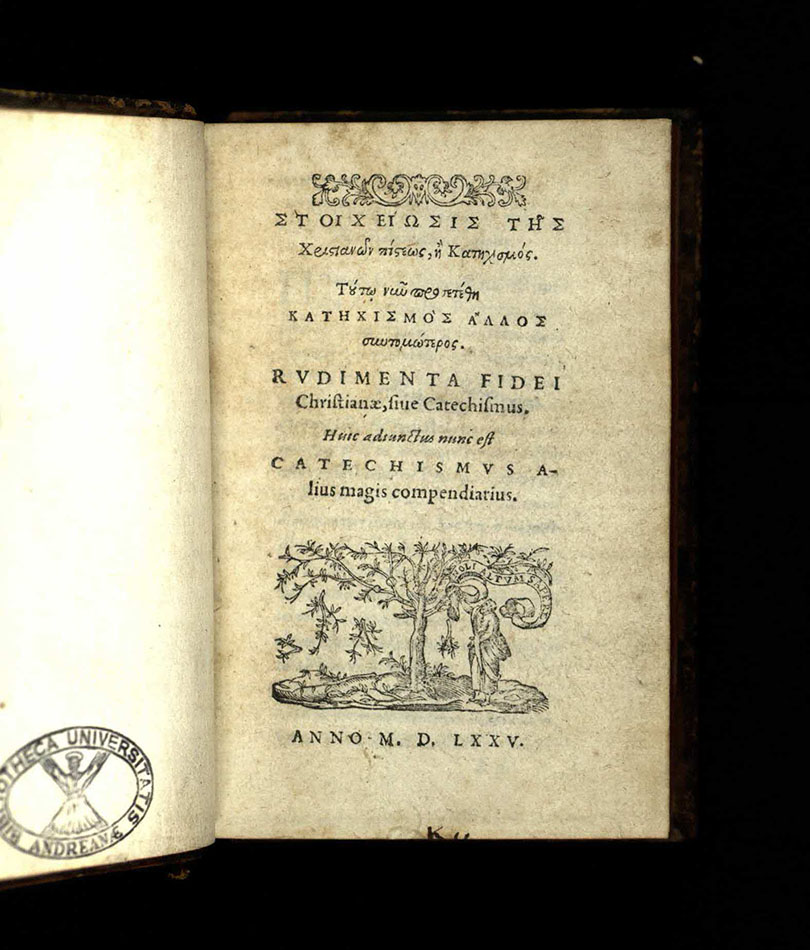

Some days ago, I came across one of these books. It was small, tied with archival tape to prevent the boards from detaching, a creaky old thing which had a beautiful title-page written in Latin and… Greek.

During the first phase of the Lighting the Past project we aim to produce records quickly and efficiently, so that our resources are made known to the outside world. We record the basic information (author, title, imprint, physical description, and subject) the majority of which comes from the title page of the book. We transcribe the title as it’s written on the title page, and if the title contains non-Roman scripts we do not Romanize them.

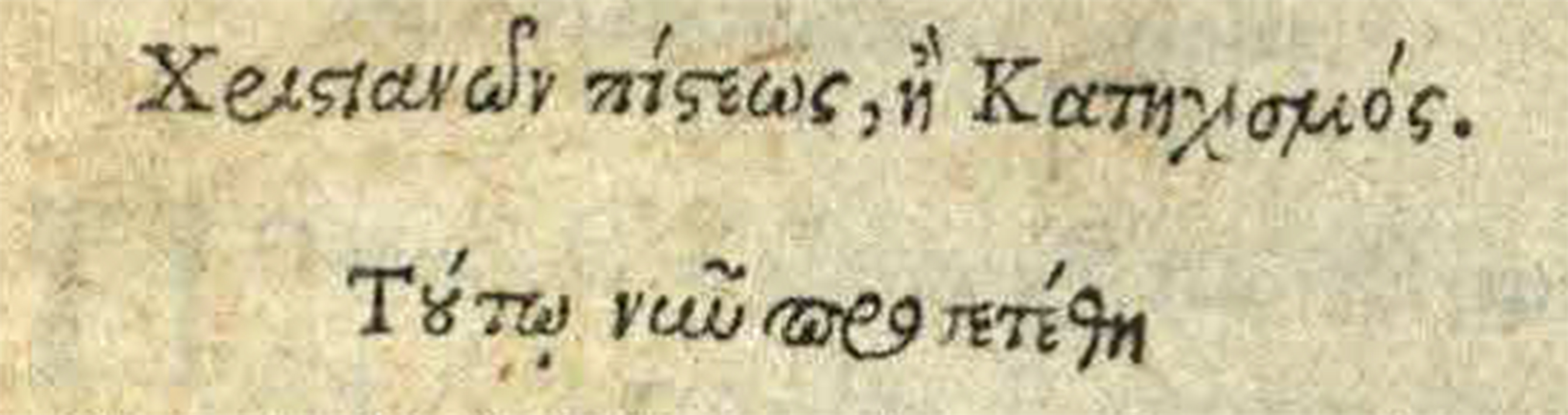

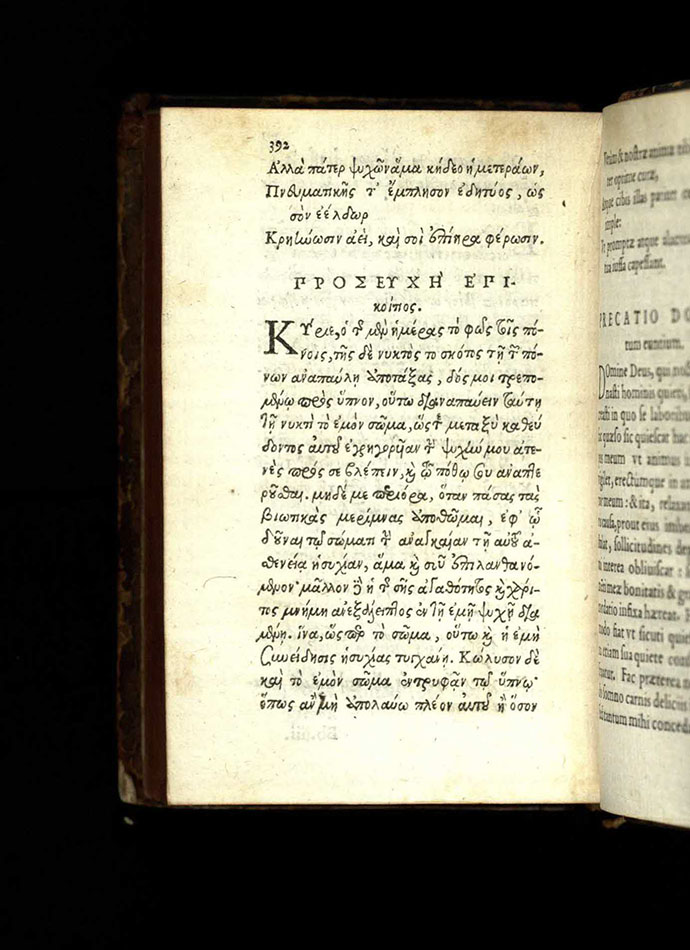

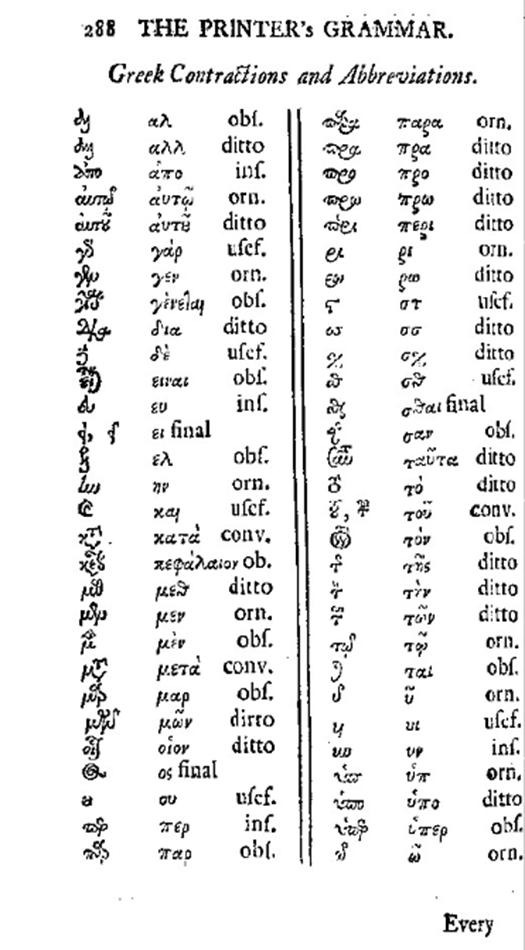

This is not a hard task if the book is in Greek, just more time consuming as we have to find the letters through the character map tool on our cataloguing software. However, if the volume is a Greek book printed in the 16th century, the title page may present Greek ligatures (combinations of two or more letters), seen frequently in early Greek printing.

Some authors have described the characters in early Greek printing as ‘dancing and jumping’ in their lines. The texts are characterized by being heavily marked diacritically, sometimes on top, but also underneath the characters.

Every time that I start to catalogue a title-page with Greek ligatures, I pass through a series of emotions that usually begin with a sense of familiarity: the writing looks vaguely similar to my own illegible handwriting; continues with a dose of speculation, how long will it take for me to decipher this?; frustration, there is no way I will be able to tell these letters apart; curiosity, wait, this is starting to make sense and, finally, a hugely satisfying feeling of accomplishment.

During the process I imagine myself stepping in the shoes of William Legrand, a reclusive man who deciphers a secret message to discover a buried treasure, the main character of The Gold-Bug by Edgar Allan Poe. I have been fascinated with The Gold-Bug since first reading the story when I was just a kid who wanted to have nightmares inspired by the House of Usher or by the swing of a pendulum in a small dark room.

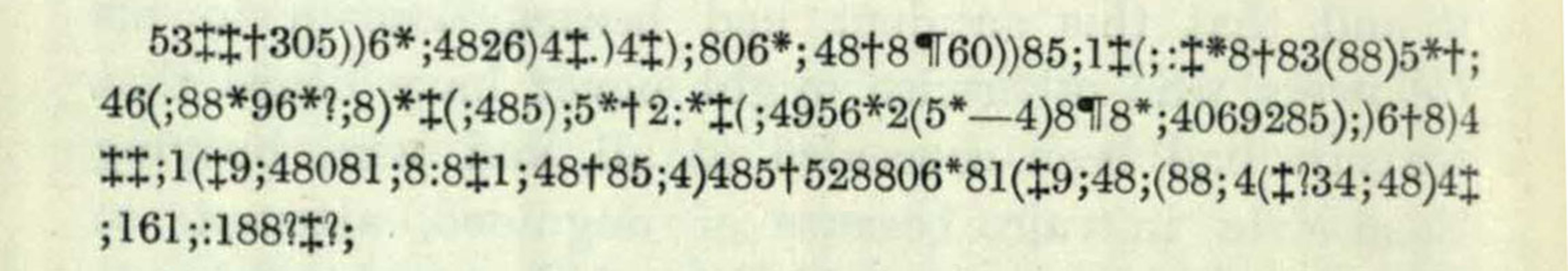

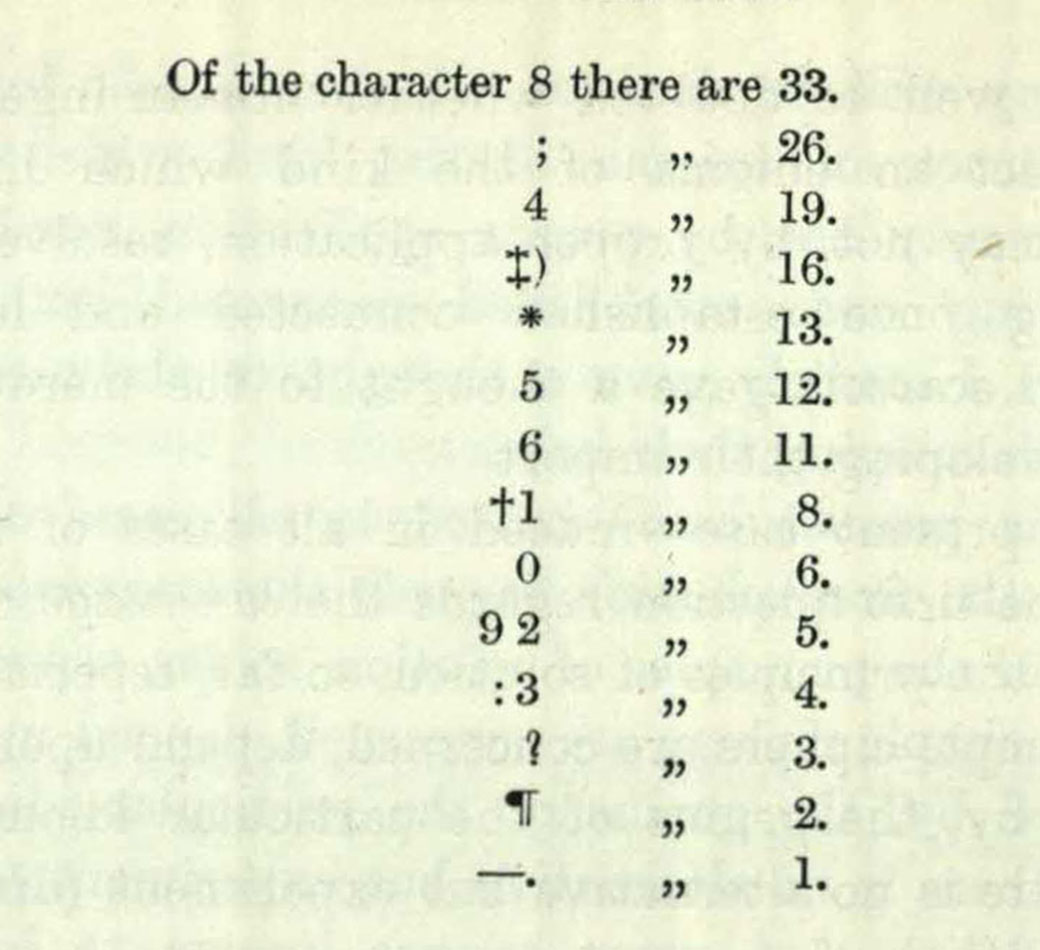

William Legrand solves his cipher using letter frequency analysis as the message is encrypted by letter substitution. He counts the frequencies of all the characters on the cipher, and creates a table of the most and least frequent characters.

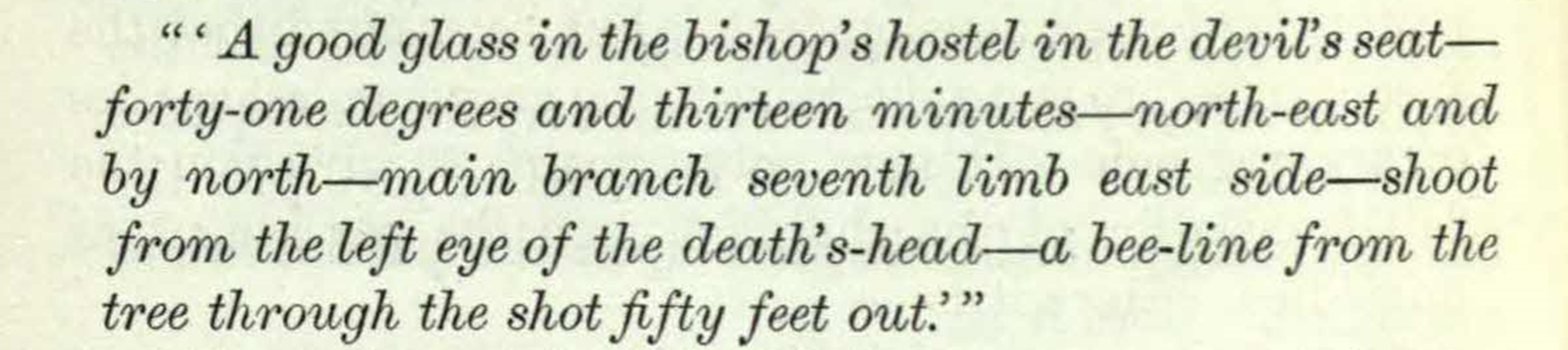

He assigns the most frequent character to the letter ‘e’ – according to his reasoning, the most prevailing letter in any sentence – and tests his assumption by checking if the character is repeated in pairs, as ‘e’ is one of the most common doubled letters in English. This proved, he looks for combinations of the letter ‘e’ with other characters, finding ‘the’ –again, the most prevailing word in the English language. He goes on, identifying words and inserting punctuation until he succeeds in un-riddling the enigma and, eventually, to find a treasure.

Encouraged by William Legrand’s success and empowered by his words: “it may well be doubted whether human ingenuity can construct an enigma of the kind which human ingenuity may not, by proper application, resolve”, I apply myself properly, ready to crack the mystery of the Greek ligatures in the beautiful title-page. For help, I turn to the tables in “The ligatures of Early Printed Greek“, an article published in 1966 in the Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies journal by William H. Ingram.

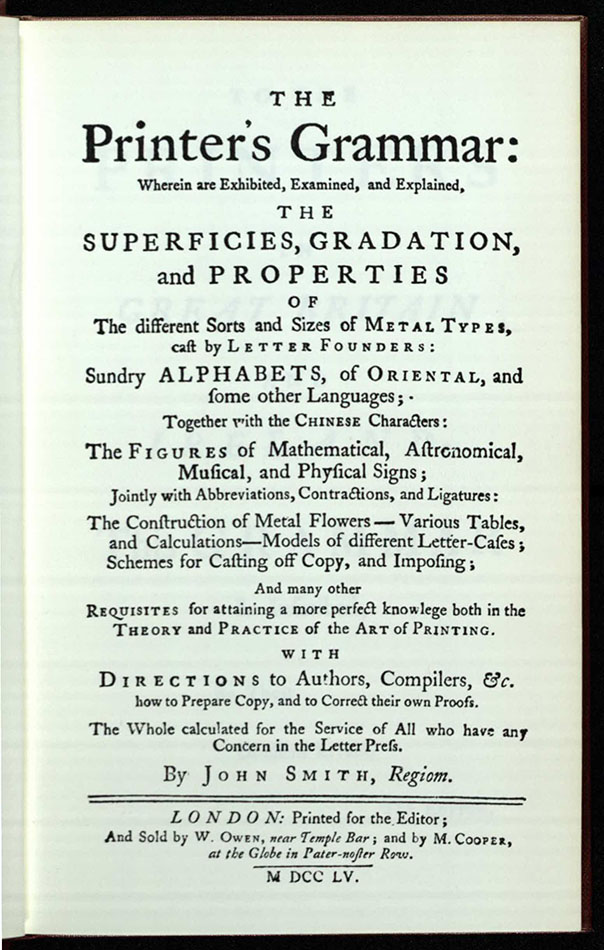

Or I might check The Printer’s Grammar, a fascinating book published in 1755 that describes the typesetting of books from an 18th century perspective (the copy in Special Collections is a 1965 reproduction).

As the pictures hint, deciphering the ligatures can be an arduous task. They might be elusive, hinting to subtle differences to distinguish one from another. I often end up pursuing a trial and error approach. But I have to admit that on finding a Greek text with ligatures, I have a much easier task ahead of me than William Legrand did with his cryptogram to the point that I sometimes wonder how long would have taken to Mr. Legrand to solve his cipher had he had access to the internet!

Pilar Gil

Lead Cataloguer (Phase 1)