Where We Find New Old Books, Chapter 5, part I: A beginners’ guide to uncovering rare book treasures: a 500-year-long tale between Parisian pages

Here two of our Lighting the Past project cataloguers retrace their exciting journey of discovery as they uncover the story of one of our new finds.

Like any great detective story, this one begins on quite an ordinary day. In the Lighting the Past office, we can catalogue over a hundred books a day; most are fascinating, some less so, but every once in a while we stumble across a true treasure. The treasure in our chapter today is a sammelband containing four 16th century Parisian works, and involves an endeavour that sent the team on a chase through 500 years of history.

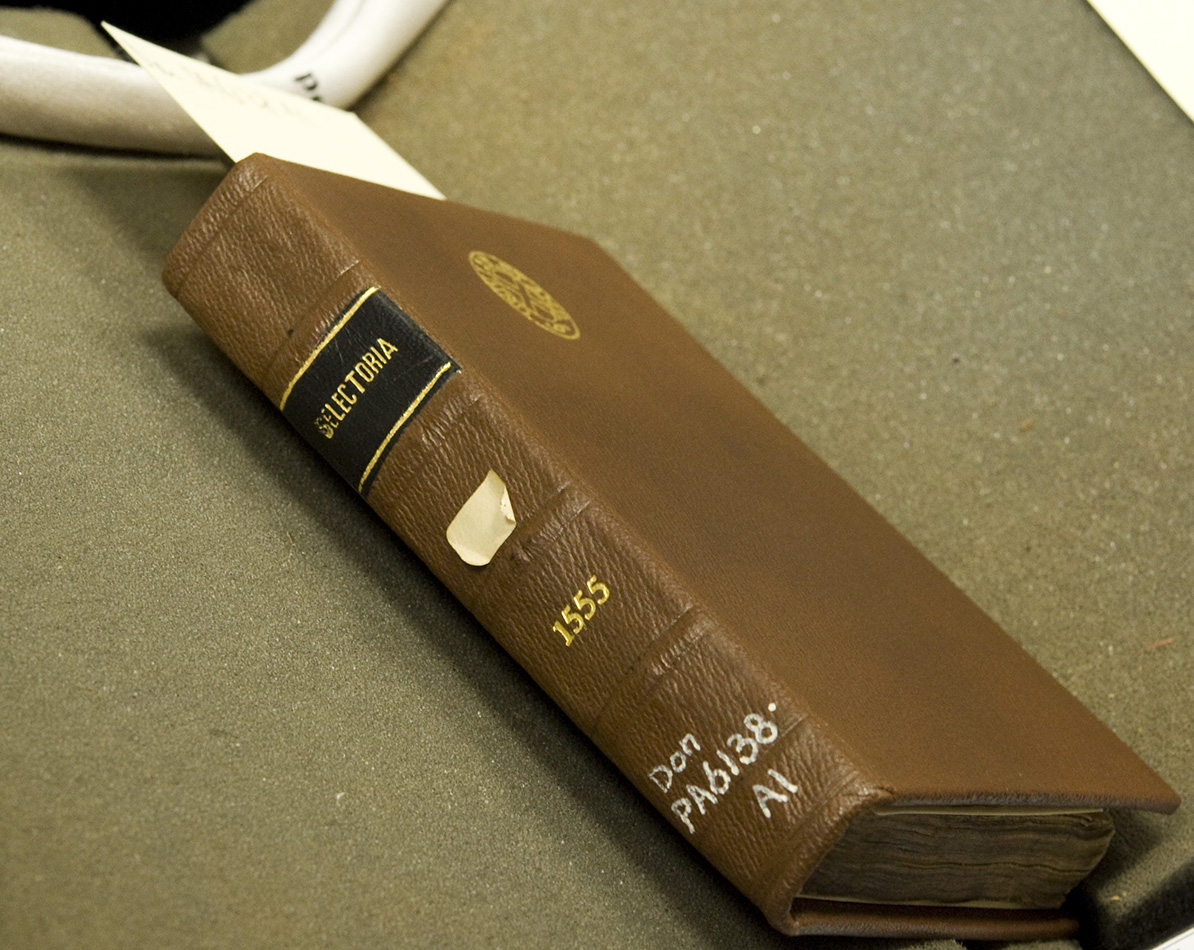

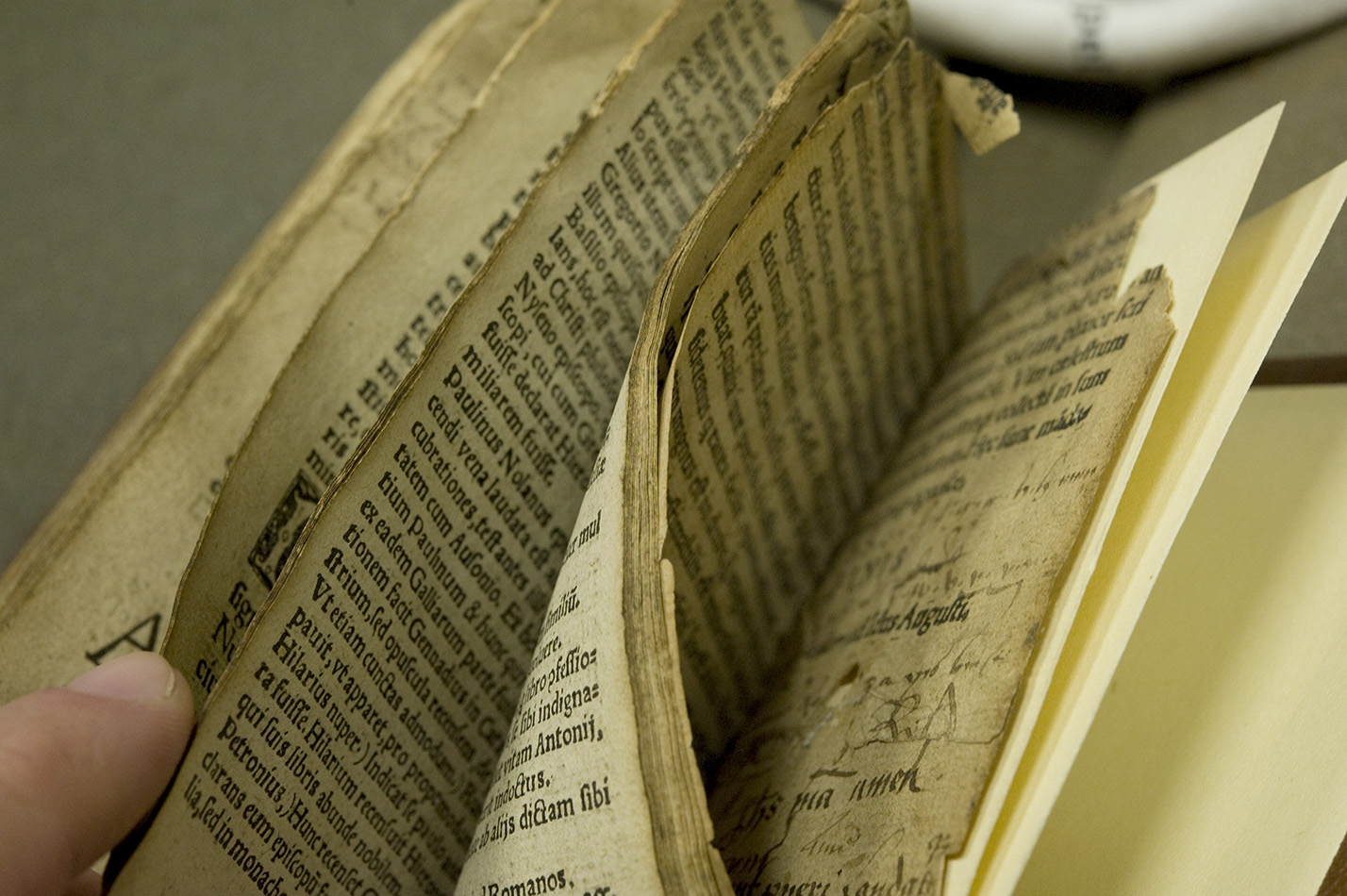

In a routine exercise while working our way through cataloguing the Donaldson Collection, we came to this volume. As you’ll see in the picture above, the modern binding seemed to belie any particularly old content; but when we opened it, we began to realise this was far from the truth. What particularly stood out to us were the beautifully aged title pages, and the incredible selection of handwritten annotations scattered throughout. It is rare to find such early material in the collections we work with and this captured our attention so much that we borrowed a camera and snapped some initial shots before we’d even discovered how rare and unique the contents were!

Through a real team effort by Pilar, our Lead Cataloguer, Daryl the Rare Books Librarian and Briony, Assistant Rare Books Librarian, we started to discover how rare the volume’s contents are. It was established that the volume contained four items:

Through a real team effort by Pilar, our Lead Cataloguer, Daryl the Rare Books Librarian and Briony, Assistant Rare Books Librarian, we started to discover how rare the volume’s contents are. It was established that the volume contained four items:

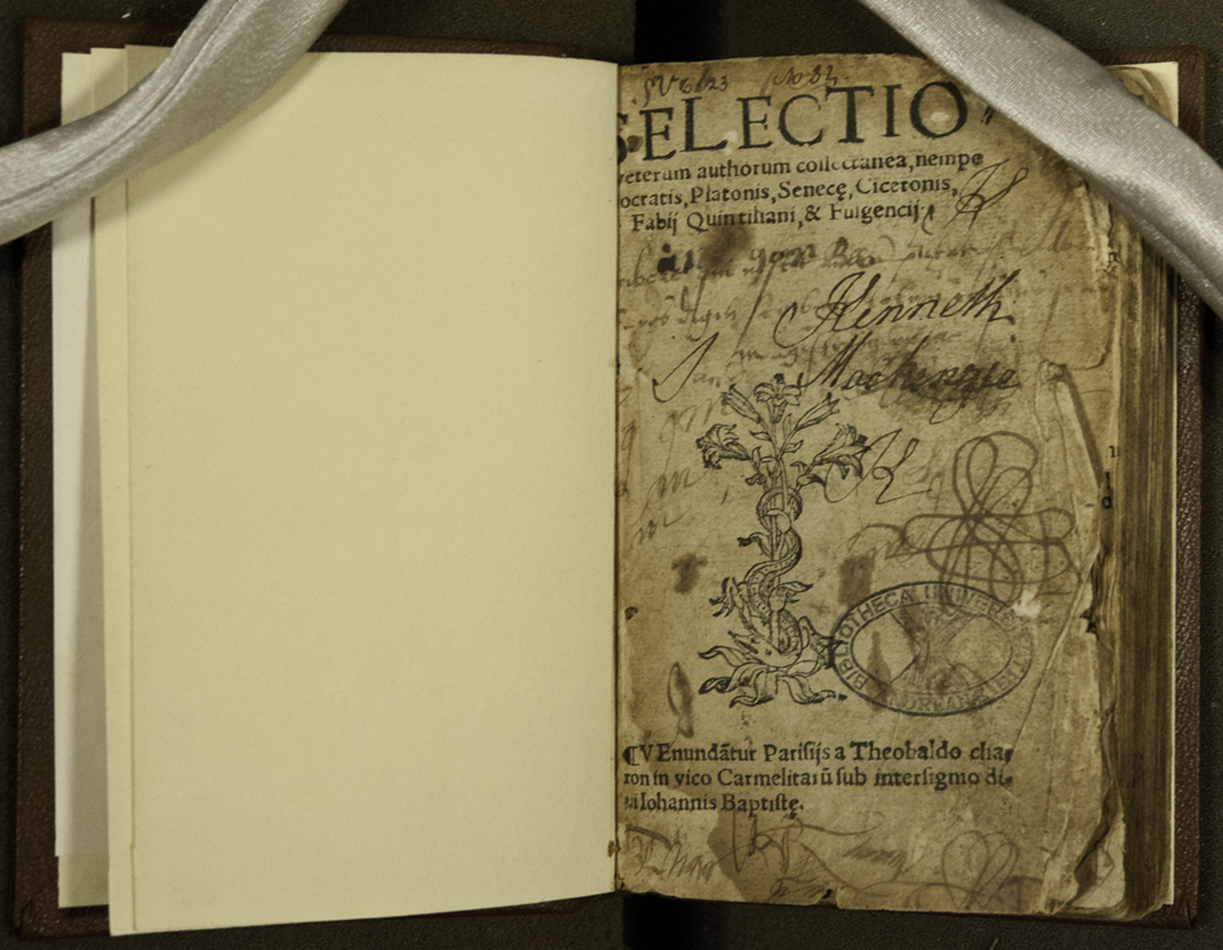

- Selectio veterum authorum collectanea. (Paris: Thibault Charron, 1530)

Unique, only surviving copy currently recorded, with no copies recorded in USTC, Bibliothèque nationale de France, &c.

This text is like a pick-‘n-mix of classical philosophers and authors; it contains quotes and proverbial sayings from heavy-hitters like Socrates, Plato, Seneca, and Cicero.

- [The Distichs of Cato] (Paris? 15–)

An imperfect, condensed version of Dionysius Cato’s Distichs, another ancient collection filled with pithy bits of wisdom.

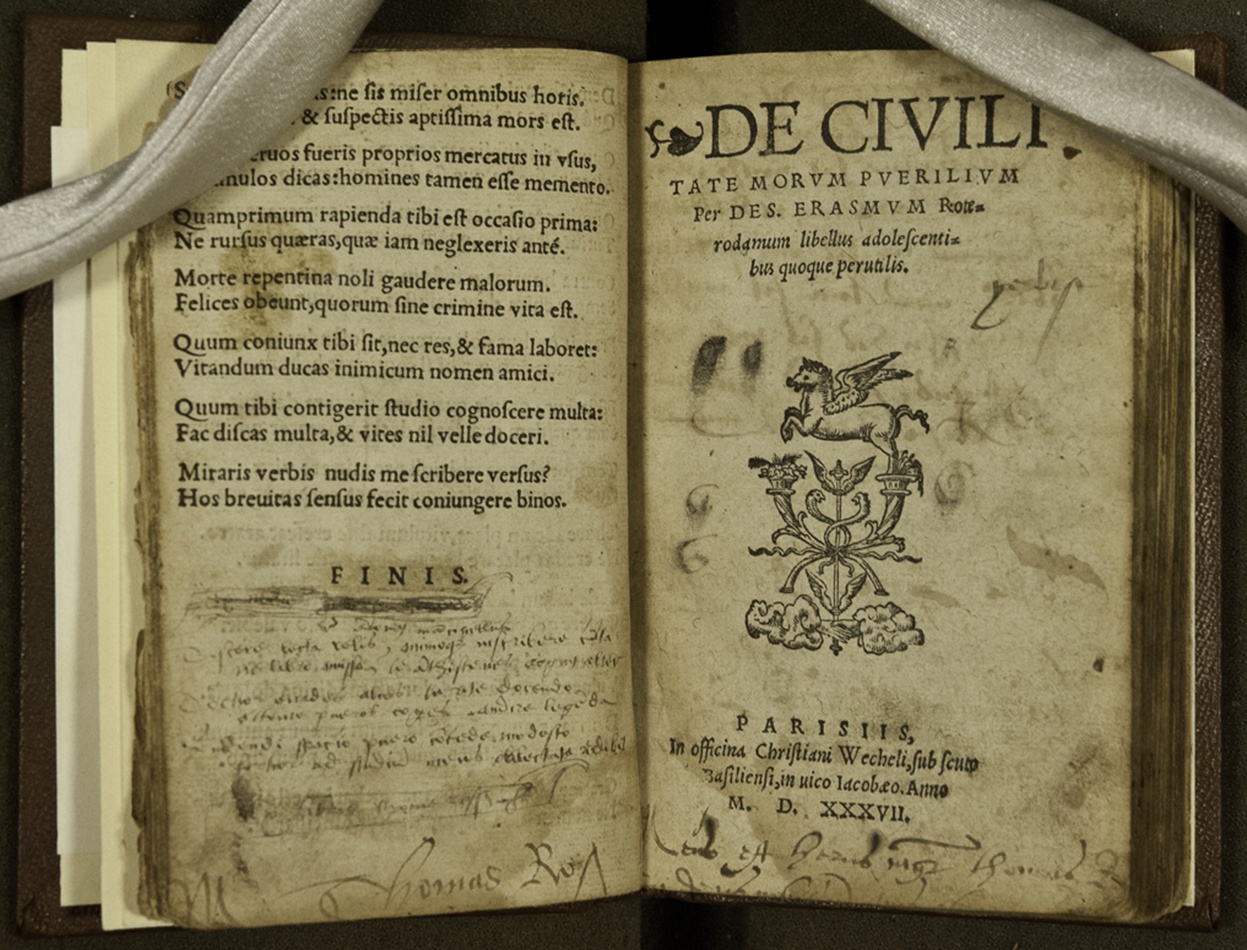

- Desiderius Erasmus, De civilitate morum puerilium. (Paris: C. Wechel, 1537).

Exceedingly rare with no copies recorded in USTC, however recorded by Moreau

An educational handbook first published in 1530, this text contains advice to boys on proper manners and instructs them on how to behave themselves in the company of adults.

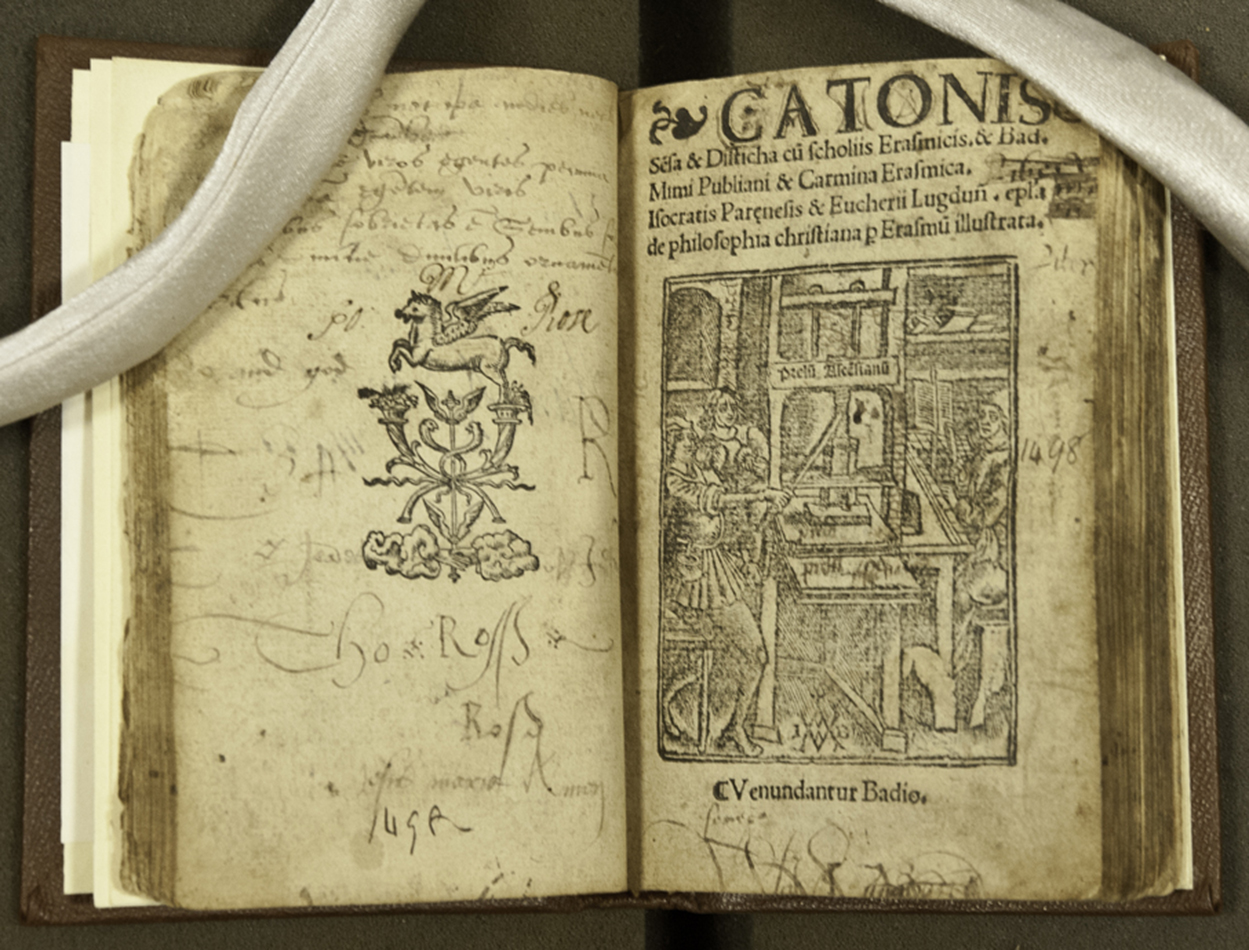

- Dionysius Cato, Sensa & disticha. (Paris: Josse Badius, 1527)

Exceedingly rare with only one copy reported to USTC

Erasmus assembled this edition of Cato’s Distichs, and published it together with a catechism of his own, Christiani hominis institutum. He also included the Mimes or Sententiae of Publilius Syrus; the Septem Sapientum celebria dicta, a collection of Greek proverbs translated by Erasmus; Isocrates’s Ad demonicum; and Eucherius of Lyon’s Epistola paraenetica ad Valerianum cognatum, de contemptu mundi.

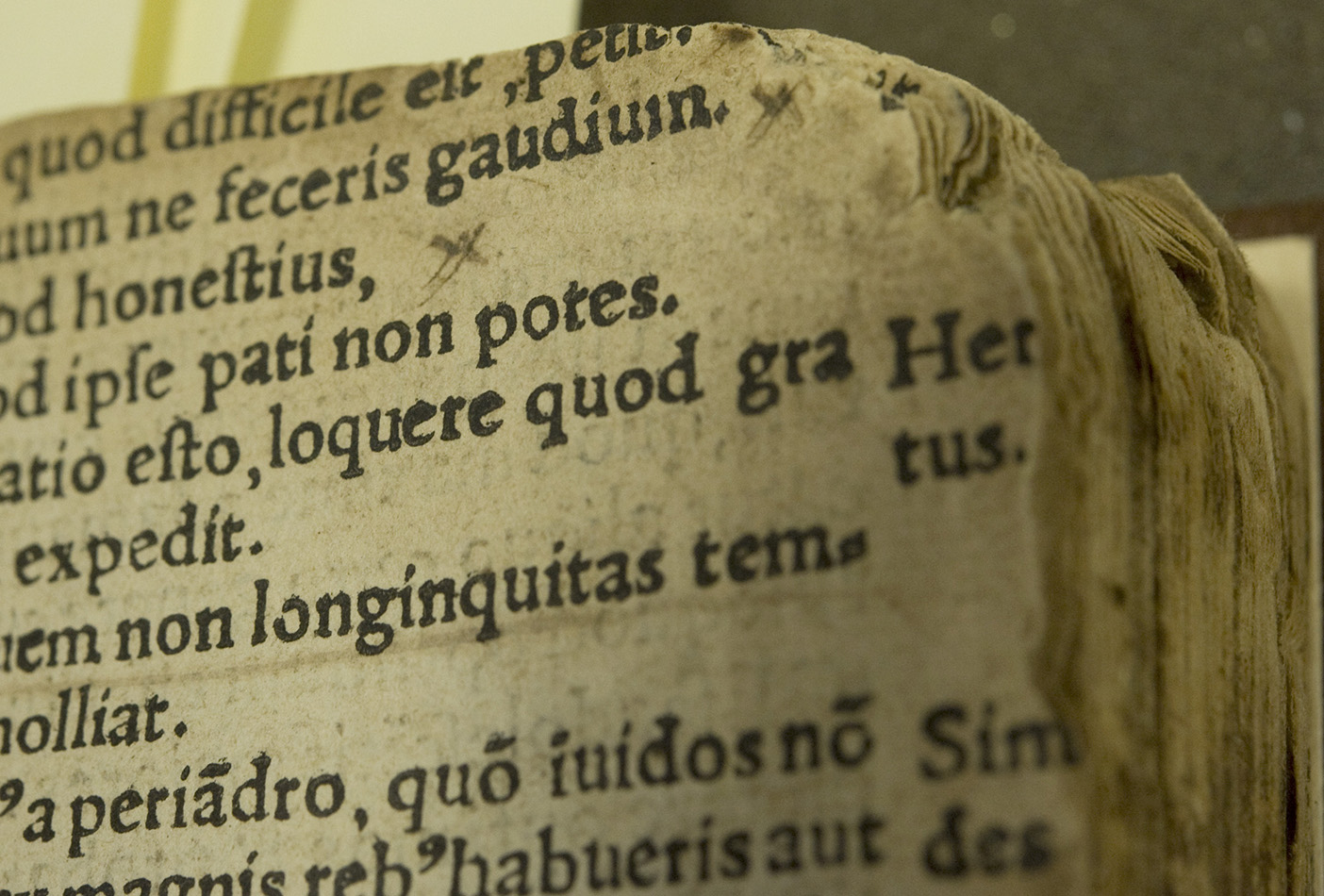

A cursory glance at these contents suggests that the book was intended for an adolescent school-aged audience. Indeed, just like schoolchildren today who underline and doodle in their textbooks, generations of readers have annotated, elaborated, and interacted with these early modern texts using their own pens. One boy, perhaps impressed by the sentiment of this particular maxim, simply marked it with a hastily scribbled x at the end of the line:

While these texts provided moral guidance and a basic introduction to classical authors, they also served as a Latin primer for their young audience. The poor quality of the paper upon which these texts were printed further attests to their intended use by students. The thin pages, browned with age, have been stained, ripped, and crumpled by centuries of clumsy fingers. It is a small miracle that they survived at all.

While the book was rebound in the twentieth century, it is possible that these texts were originally bound together much earlier, especially given their Parisian origin and similar subject matter. Faint vestiges of a crudely painted red and green fore-edge decoration are also still visible on all three sides.

Finally, annotations in a sixteenth-century hand occur throughout the volume, and at least one previous owner, Thomas Ross, possessed these texts as a single volume at some point in the late-sixteenth or early-seventeenth century; his boyish signature, initials, and other marks of ownership crop up on the pages of each of these four texts. So, although we cannot say with absolute certainty, it seems most likely that these texts were bound together at some point between 1537 (the latest imprint date) and the end of the sixteenth century (the ownership of Thomas Ross) for the express purpose of the moral and philosophical education of young boys.

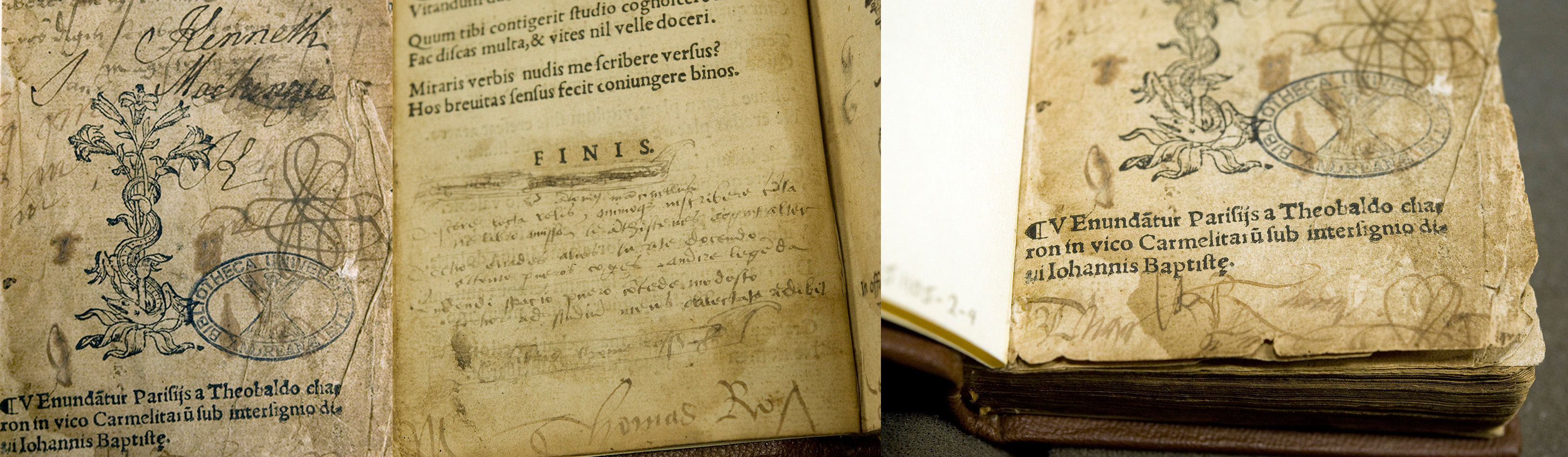

Naturally, we were drawn to investigate all we could about this completely unique copy of Selectio (1530). There wasn’t much to go on: we had a printer’s device, a few signatures and inscriptions, and a single imprint. Armed with what little information we had, we set about our research.

We began with the printer’s device. Always associated with a specific person, these marks can be as good as, if not better than, an actual name! The Universitat de Barcelona has a fantastic database of printer’s devices which can be scoured using key descriptive words; we tried a whole combination of: snake, serpent, plant, leaf, tree, coiled, flower, flowers, lily, lilies – all to no avail. The closest we found was this example, from a French printer c. 1528-1538; it was our rough time slot, but it wasn’t in Paris, nor did it match exactly – the flowers appear to be roses, the serpent is coiled inversely from our device, and there are the initials ‘GR’ on either side. No luck here.

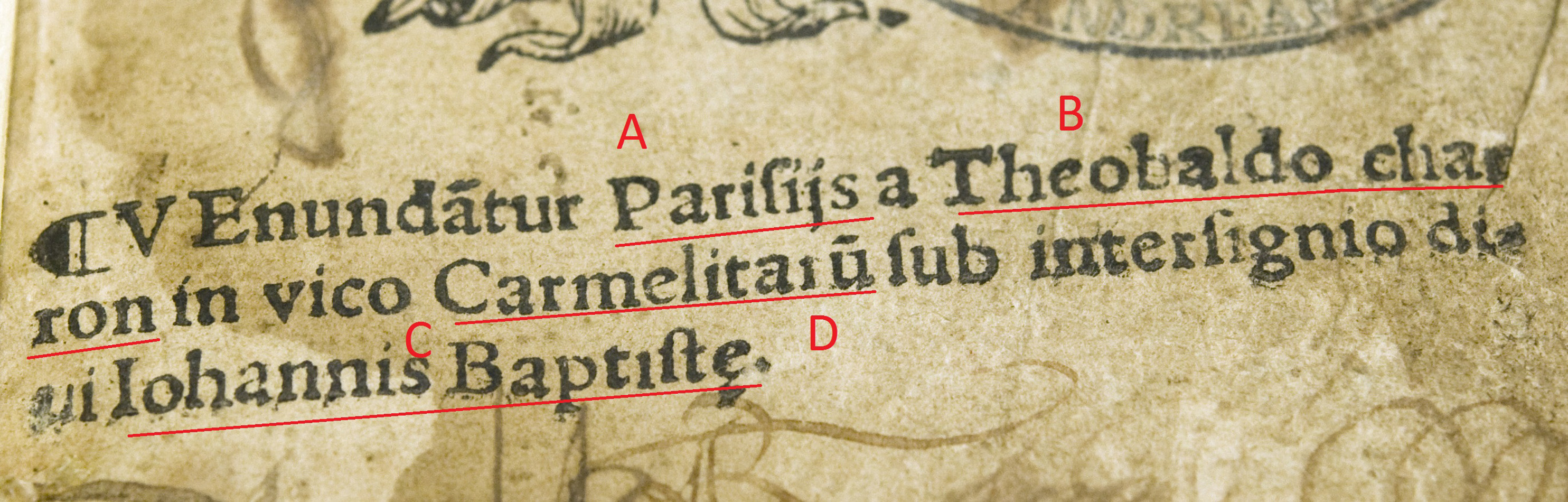

But searches for Peter Charron returned nothing either. We thought this might be the end of our journey – but after instead searching for his book Of Wisdom, we discovered his name in French was actually Pierre Charron, a Catholic Theologian! Suddenly it occurred to us – what if Theobald/o was an Anglicised/Latinised version of a French name? A quick Google search revealed that it was, and finally we had a correct name – Thibault Charron.

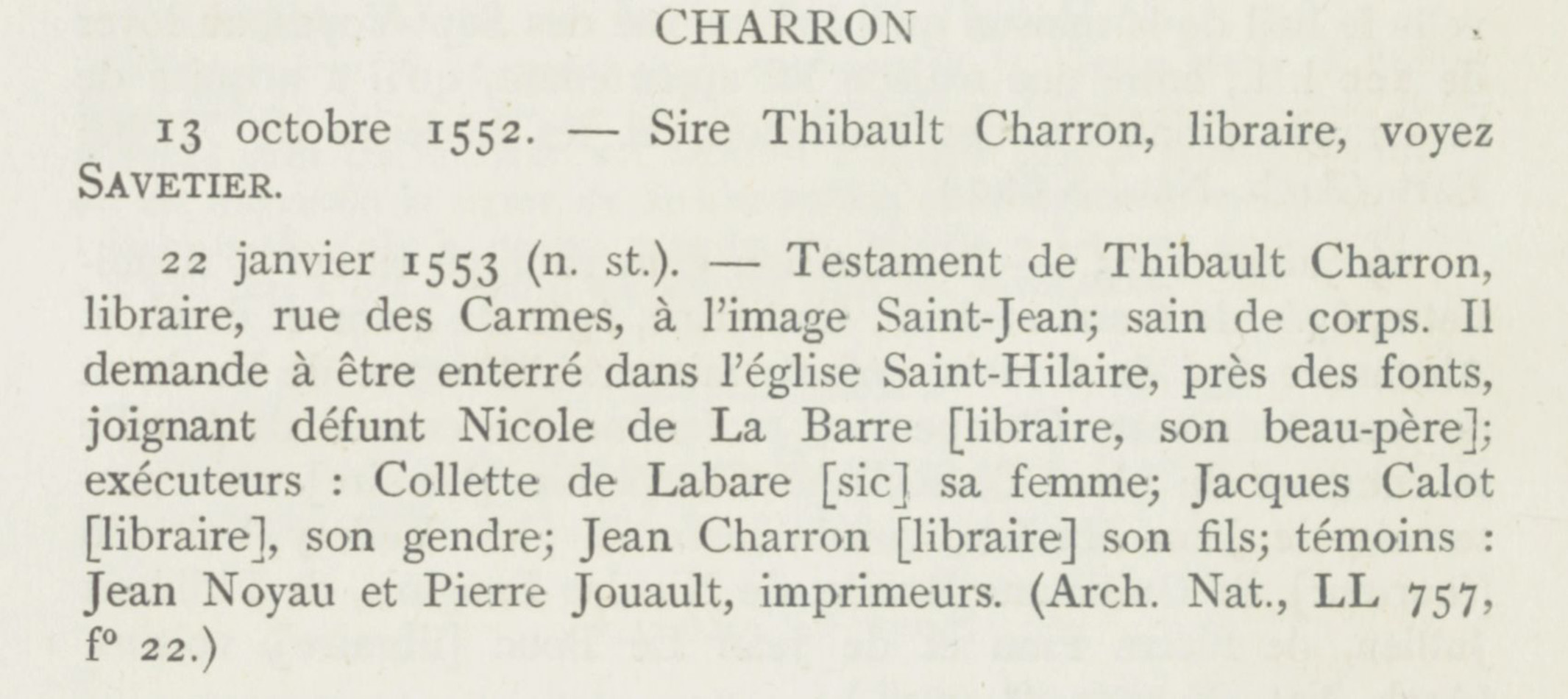

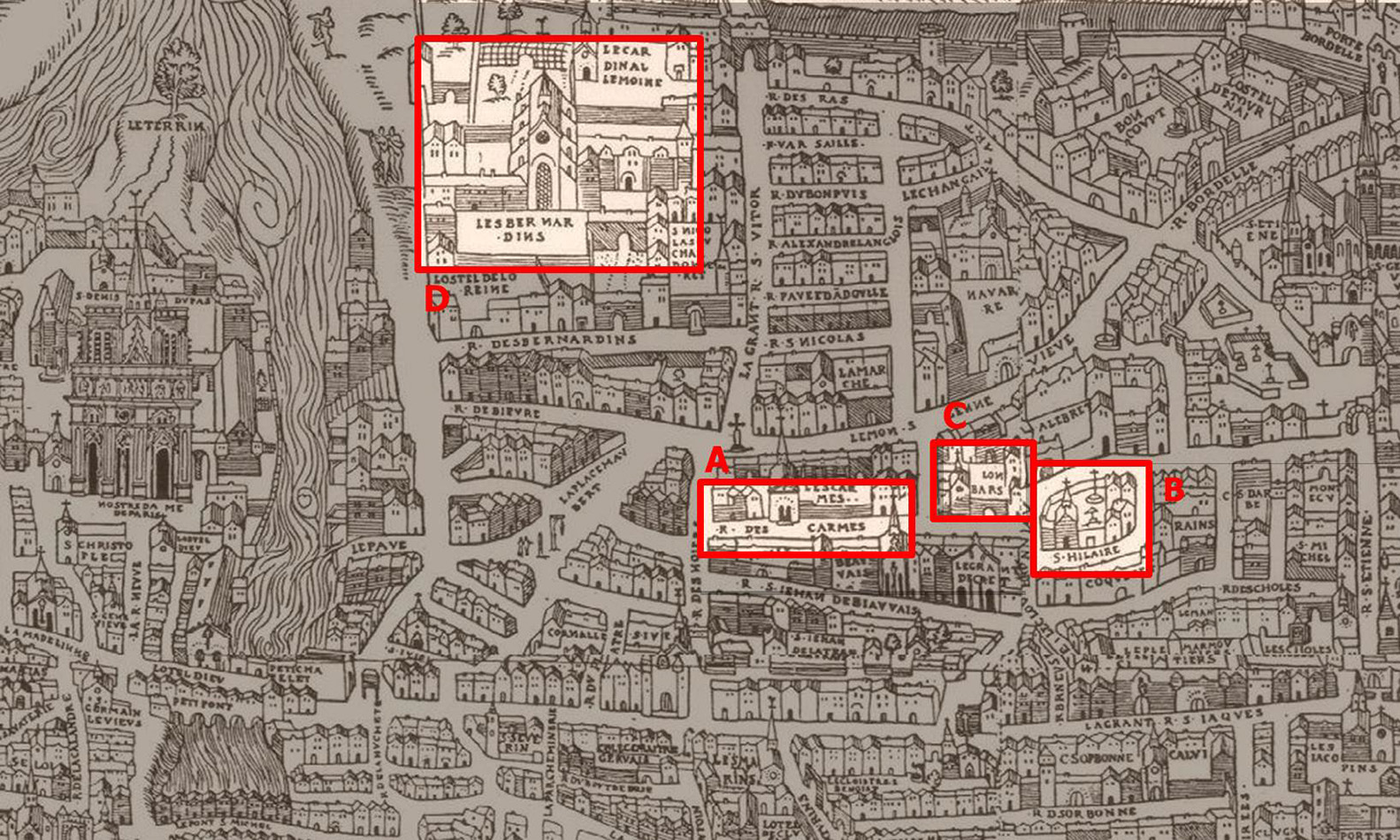

Excited that we had finally prised open the lid on this treasure chest, our searches for Thibault Charron led us to a record of his Will and Testament, in a book of collected documents from printers etc. in Paris in the 15th and 16th centuries. Filed in 1553, he requested to be buried with his father in law Nicole de la Barre, who had been buried at the Church of Saint Hilaire. His current wife, Collette de Labare, served as one of the executors. It also listed his occupation as a bookseller, which further corroborated our match, and crucially, it gave us his address – rue des Carmes, à l’image Saint-Jean! This was our ‘Iohannis Baptiste’ and ‘Carmelitai(u?)’ from the imprint!

Having established Thibault Charron’s presence on the rue des Carmes, we turned to WorldCat. A quick search for Thibault Charron brought up two matches in the printer field in the 16th century. The first was from 1520, which listed Thibault alongside another printer, Nicolas de la Barre – perhaps this was the same de la Barre family that he married in to, and he was working here with his father-in-law! The second was particularly curious. The title was almost identical to our copy, but had added two philosophers; Pythagore and Chilonis. Most interesting, however, was that Thibault Charron had not printed this work; but there was a note that said ‘Marque de Thibault Charron, utilisé par R. Du Hamel en 1536’.

Instantly alert, we scrambled to see what more we could discover. The mark of Thibault Charron, used by R. Du Hamel in 1536? Was this the same as the printer’s device in our work, that we had searched so fruitlessly to find? We followed the catalogue location in WorldCat to the record (The link can be temperamental – try navigating to the page a second time!) in the National Library of France’s catalogue, and indeed, it appeared a Richard du Hamel had used Thibault Charron’s mark! But what was the mark? Did it match our own? We had no way to corroborate it, as there were no pictures or descriptions. It was here again that Daryl dropped the final piece of the puzzle in place for our treasure.

Daryl directed us to the CERL Thesaurus, where he had found the entry for Richard du Hamel – and under the list of his known devices, in the first entry, described as being taken over from another printer, was our mark. Not only that, but the CERL Thesaurus provided a link to Philippe Renouard’s work again, where we found the following description:

‘Richard Du Hamel, libraire, 1532-1548 … Il emploie en 1536 la marque du Thibault Charron.’

That was it. We had come full circle – we had confirmation that our mark was Thibault Charron’s device, discovered exactly where he lived and worked, who he had married, how many children he had, and so much more. What began as a dead-end search had revealed a fantastic and vibrant picture of a 16th century Parisian bookseller, the little-known Thibault Charron.

Look out for Part II for the exciting conclusion of ‘a beginner’s guide …’

-Kieran Cressy and Emily Savage

Phase 1 Cataloguers, Lighting the Past

Now this really IS something, and so exciting to someone who knows Paris like the back of her hand. It can all be pictured even today in looking at the footprint of the 'Latin Quarter'. But in all these bibliophile comments, what really interests me is how these books came into the possession of St Andrews' University Library, or rather into the collections of the original donors. Perhaps Principal Donaldson knew a thing or two, and something of which today you have had to work out from the beginning. The plus is that French artisan and mercantile activities are wonderfully archived and recorded by the several remarkable libraries of Paris.

Fascinating post, thank you :) The word is 'Carmelitaru[m]' - 'in vico Carmelitarum' from the imprint means 'in the village of the Carmelites', (as in the religious order) and refers to the 'rue des Carmes' where Charron worked, as you noted.

Thanks Anna for pointing that out. We have made the correction to 'Carmelitaru[m]'. Glad you enjoyed the post!

I understand that there was an altar to St Ninian in the Carmelite church in Place Maubert, Paris, where Robert Keith was buried in 1551. He was Commendator of the Abbey of Deer. This may hint that your Thomas Ross was of the Highland family, of Balnagown.

Brilliant detective work ! If you have not yet identified Thomas Ross may I act as a potential witness to the hunt? In the late 15th-early 16th centuries there was an active clutch of Rosses in Ayrshire and several were notaries, the best-known being Gavin Ros, whose protocol book has been published in modern times. Thomas Ross of Montgrenane (by Kilwinning) is mentioned in a charter of 1546. Another (or perhaps the same man) is a Thomas who was a charter witness ten times between 1513 and 1528, and 'arbiter' in 1515 and acting as 'ballie' for James Dunbar of Cumnock in 1517 (Gavin Ros Protocol Book). The closeness of the Carrick Rosses to the Kennedys of Cassillis brings in Quintin Kennedy, abbot, then commendator, of Crossraguel Abbey, who was educated at the universities of St Andrews and Paris. Qunitin's name appears in the Acta of Paris University between 13th November, 1542 and Easter, 1542/3. {Innes Review xxiii, 2, p.152, Autumn, 1992} {C.H. Kuipers, Two Eucharistic Tracts of Quintin Kennedy, 25-26}

Thank you for your insights. Part II of this post will delve into some of the potentials of who the Ross's were. We look forward to reading your comments and suggestions about our theories.

Reblogged this on jamesgray2 and commented: I love old books, no matter how worn or humble, there is SO much to learn if we take the time.

[…] Here, our Lighting the Past team complete the story of their recent adventures uncovering the story of one of our new finds. […]

[…] this blog post title intriguing? “Where We Find New Old Books, Chapter 5, Part I, A Beginners’ Guide to Uncovering Rare B… Read Part II […]

[…] Furthermore, during our cataloguing, we have also discovered a number of unique books and two incunabula in his library. Donaldson’s passion for collecting (and also presumably reading) books is clear […]

[…] something straight out of the Da Vinci Code, or Indiana Jones – I highly recommend you check out part 1 and part 2 of the blog post that Emily and I wrote on […]