Reading the Collections, Week 44: The Mackenzie Correspondence, 1685-1691

I wonder yow writ not to mee.

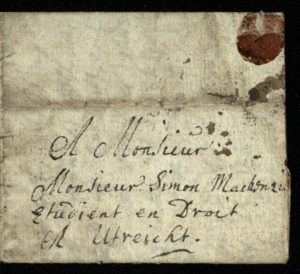

Like so many parents or guardians of young people at university, Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh was not impressed by his nephew Simon’s epistolary abilities, much less his money management. A bundle of 37 letters – worn, torn, and dirty – from the Fraser-Mackenzie of Allangrange manuscripts in Special Collections lets us reconstruct the tumultuous relationship between uncle and nephew as they weathered the storms of youth, age and revolution in late seventeenth-century Europe.

The first letters date from the summer of 1685 when Simon had been sent by his uncle to study at Christ Church, Oxford. His uncle had suggested he might train for the ministry, but as far as Simon was concerned it “matters not what [career I pursue] if it be to gett money: for now I begin to find the need of having money”, a sentiment which was common enough amongst the fast living, hard drinking Christ Church undergraduates of the 1680s. Two years later Simon travelled to the Low Countries to continue his education in the Dutch universities, like many young Scots of the time, and his uncle, writing to him in Leiden soon after his arrival observed with a touch of acerbic humour that “I am glad yow hav evited your danger at sea & made ane improvment in your devotion by it”.

Over the next three years Simon went on an academic peregrination from Leiden to Rotterdam to Utrecht with a stop in Franeker on the way. His wandering habits echoed his vacillation over a choice of career. After initially following his uncle’s advice and beginning to train as an Episcopal minister, he wrote in some anxiety to his uncle that “I’m hopefull you are not displeased with mee” for giving up that plan. His uncle, with surprising calm, wrote back that “I wish yow to study law if yow will quiyte divinity” – George himself was a famous lawyer, as well as a controversial politician, and had no great objection to his nephew’s volte-face. At least not at first. Simon badgered his uncle for favours, hoping that George’s position in the legal profession might give him an extra edge, leading the older man to snap back: “Blame not mee for changing your study but your own Presbiterian humour I was for your being a church man . . . but I cannot help yow as a Lawyer”.

As the decade came to a close, however, personal concerns began to be overshadowed by political ones with the invasion of Britain by William of Orange and the subsequent flight of James VII and II in December 1688. George, a darling of the outgoing regime, began to fear the worst as Simon tried to reassure him that rumours of his imminent downfall were “onlie the extravagant talking of some younge blades that have no kindeness for you”. After a lifetime working for what he believed was Scotland’s good, George left his native country forever in the spring of 1689, entering into a voluntary exile in England.

By 1691 George was in bad health and Simon, now returned to his childhood home at Fortrose, anxiously awaited letters sent by his uncle’s faithful friend Alexander Monro. On 31 March Monro was writing that “your uncle at present is very low and his body extremly worn and he is no sooner recovered from one bad sympton but another appears” – preparing Simon for the worst. Monro wrote again on 4 April that “I had occasion to speak with your Uncle Sir George about yow at some lenth he entertains no prejudices against yow on the contrary he prayes God heartily to bless yow and all your endeavours”; despite their stormy relationship, George was forgiving Simon unreservedly. George himself added a shaky postscript to Monro’s letter, writing to Simon that “I thought fit to leave yow my blessing under my own hand as I doe also to all our familie”. Shortly afterwards he suffered a haemorrhage and died on 8 May 1691 at his lodgings in Westminster. Simon went on to become an advocate in Scotland, had fifteen children, and died ripe in years in 1730. He named his eldest son George.

It’s this mixture of the personal and the national, I think, which gives the Mackenzie correspondence such interest. Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh was a famous man in his day and is now recognised as one of the pioneers of the Enlightenment in Scotland, but these letters blend fears of revolution and news of new scholarly books with a very intimate narrative about the difficult but deeply loving relationship between an orphaned boy and his domineering politician uncle, a narrative which is deeply embedded in the culture of late seventeenth-century Europe, but which is timeless in its depiction of a young person at university, trying to understand their place in an uncertain and changing world.

Dr Kelsey Jackson Williams

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow

Loved reading these. I remember dropping these papers off at St Andrews with my father Peter Fraser-Mackenzie. Thank you for the work you have done.

Hi Georgie, great to hear from you and glad to hear that you enjoyed the post.

This is fascinating - though I found the writing very difficult to decipher! Just to add as a postscript, the nephew Simon did die in 1730, but not in his bed; he drowned in the River Orrin, returning from a visit to Fairburn. (History of the Mackenzies by Alexander Mackenzie, published in 1879, which is online at https://archive.org/details/historyofclanmac1879mack)