Reading the Collections, Week 45: The papers of Alexis Aladin

When I was tasked with looking for material for a school session on the Russian Revolution, I was dubious as to how much Russian material we would have here at the Special Collections in St Andrews. As I searched the catalogue for all things Soviet, the name ‘Alexis Aladin’ repeatedly cropped up, and as I looked into who he was, I quickly realised that this individual, unfamiliar to me, was certainly worthy of closer study.

Born in 1873 to a peasant family, Aladin attended the same school as Lenin and was expelled from university for political agitation in 1896. By the time of the 1905 revolution, he had risen to leader of the Trudoviks, the revolutionary peasants’ party, and consequently suffered exile under the Tsar, imprisonment under the Bolsheviks, and gained glory and promotion in the Civil War.

During exile in England, Aladin befriended Fife paper mill owner Sir David Russell, and it is for this reason that some of Aladin’s papers are here at the Special Collections: Aladin bequeathed his papers to his friend, and in turn they became a small part of our David Russell Collection. This material is spread across five boxes which largely consist of Aladin’s sizable correspondence with Russell. Here I will focus upon just one folder of his personal documents.

I should immediately say that although this blog series is entitled ‘Reading the Collections’, my ability to read Russian is non-existent and so I am indebted to the catalogue entries made by Professor Reginald Christian (Aladin’s biographer) which allowed me to make sense of these documents. Yet as I hope this post and its accompanying images will demonstrate, one does not have to be fluent in Russian to appreciate how visually interesting these very personal sources are.

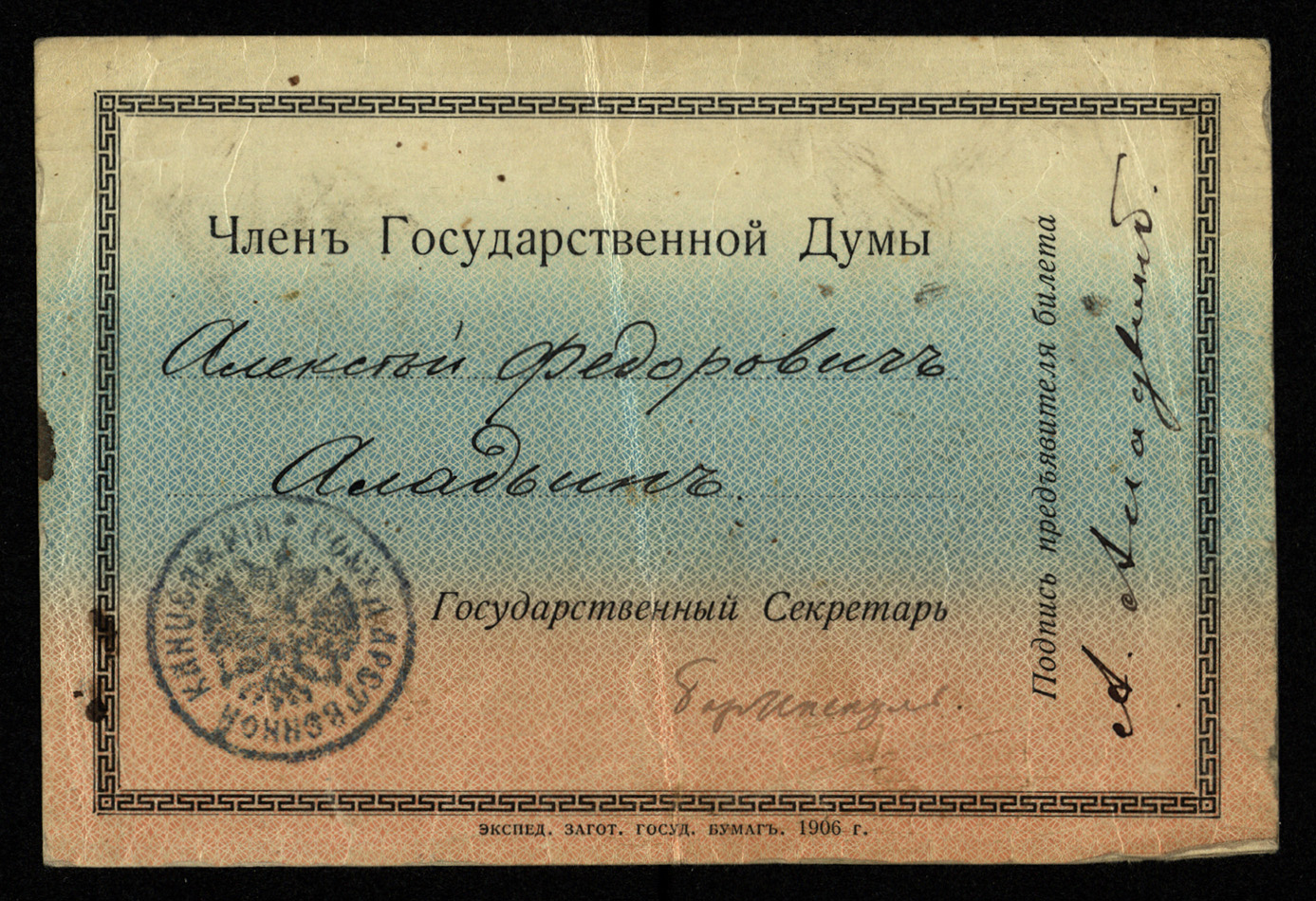

Aladin rose to prominence in the aftermath of the 1905 revolution, when he was elected to represent the revolutionary peasants’ party in Russia’s first elected parliament, the Duma. His membership card of the State Duma, written upon Russia’s national colours, was issued at its opening in April 1906 and was valid until 1907. However, the Duma only lasted for seventy two days before it was dissolved by the Tsar and Aladin was summarily exiled to England.

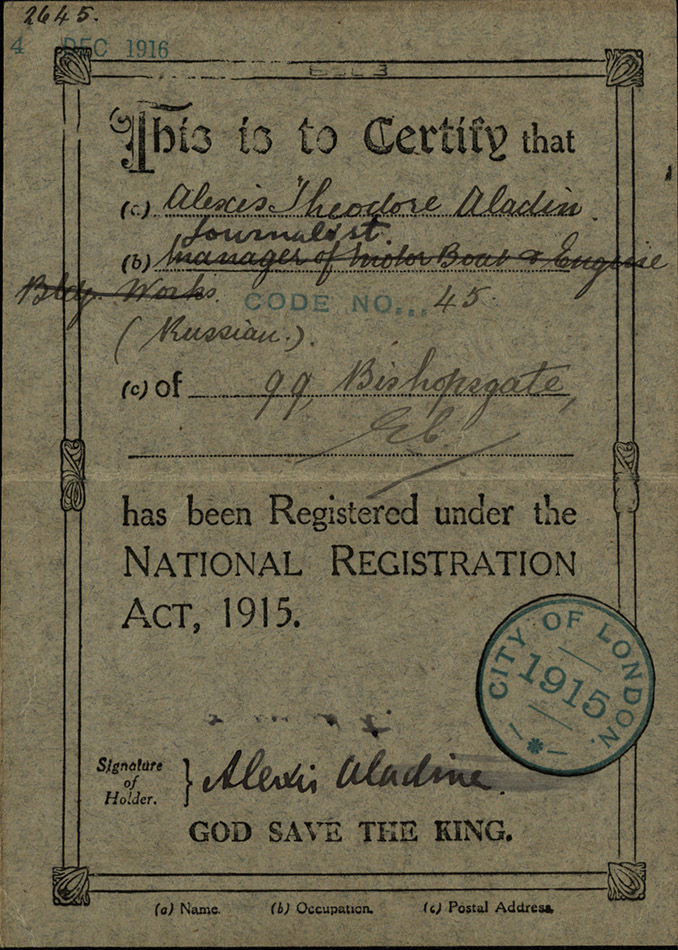

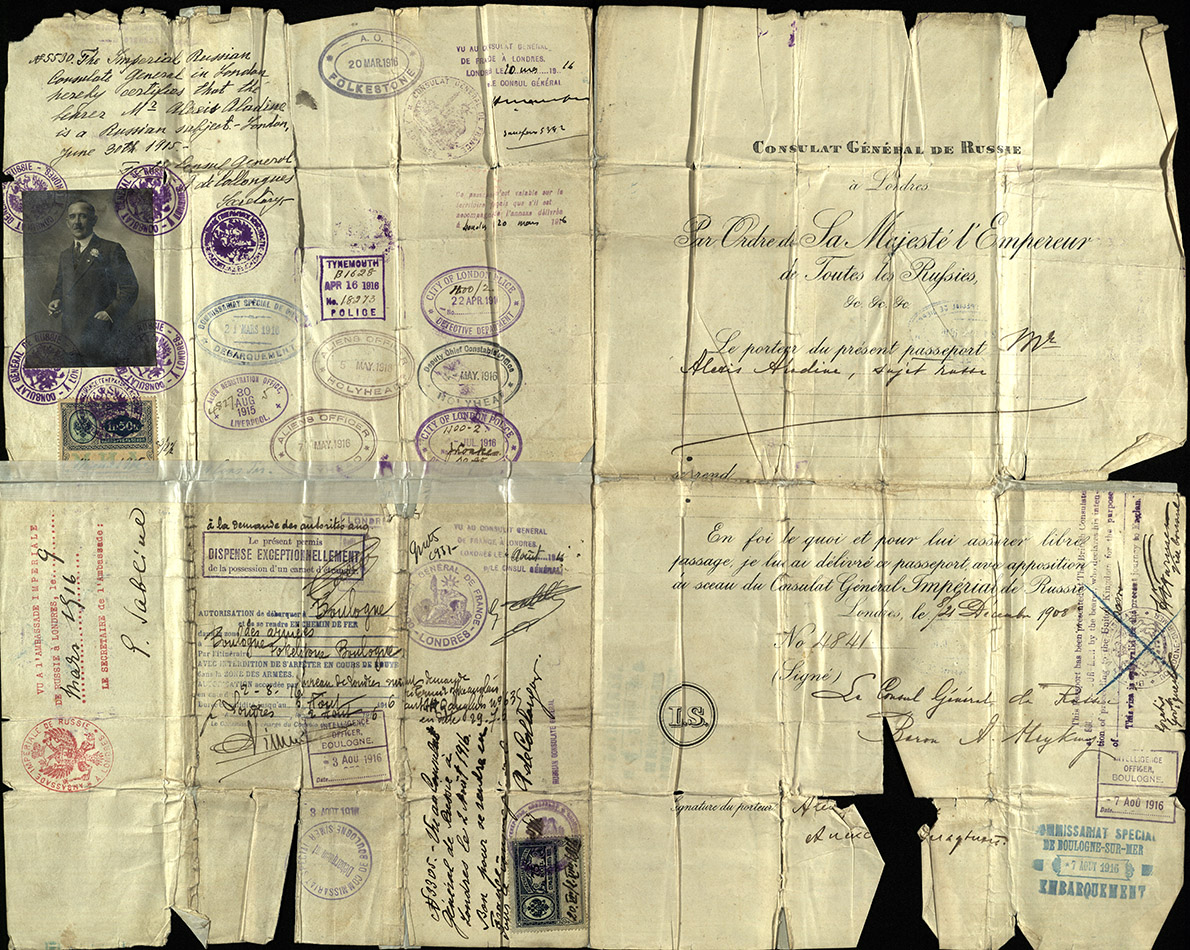

After several years spent lecturing and working for a motor boat company, Aladin secured employment as a journalist upon the outbreak of war in 1914. The material collected over the next couple of years provides an interesting insight into what life was like in Britain for foreigners during the First World War: Aladin’s internal passport is littered with Alien Office stamps closely recording his movements around the country, such as his trip to Holyhead immediately after the Easter Rising where he was sent to investigate Irish revolutionary groups.

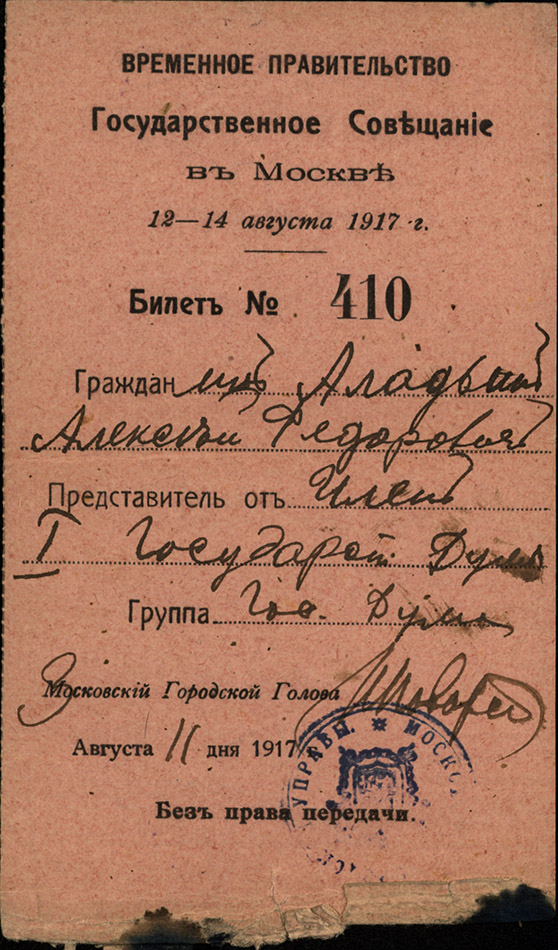

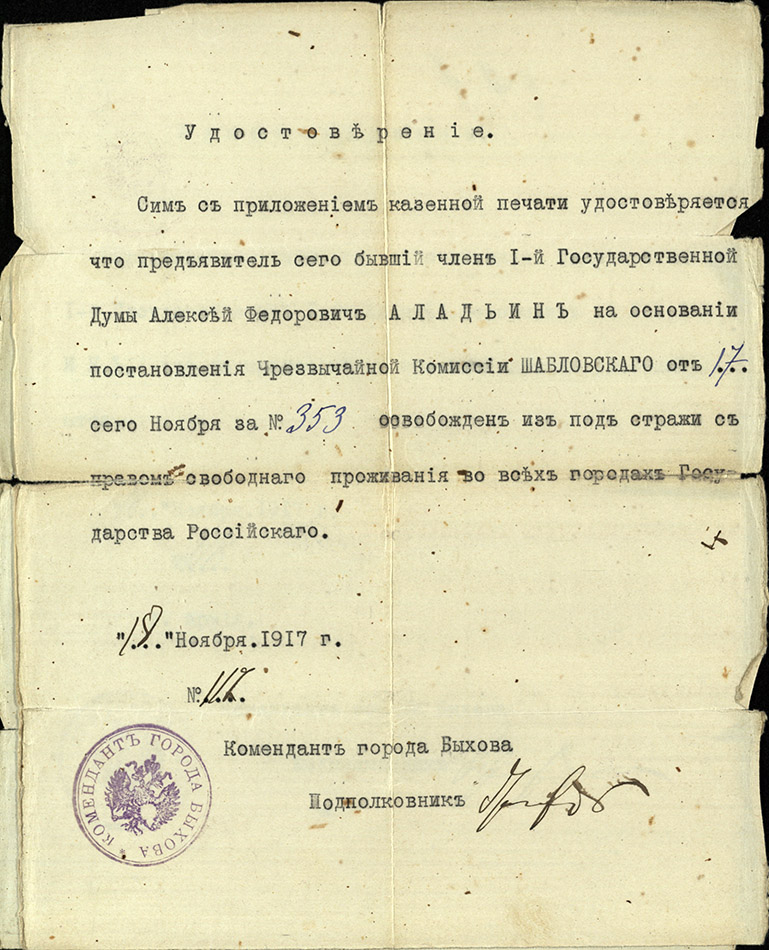

Aladin finally returned to Russia in the summer of 1917 and in August was issued this ticket to the Moscow State Conference by the Provisional Government. Around the time of this Conference, Aladin aligned himself with General Kornilov who later that month attempted a coup. Kornilov, Aladin and other allies were consequently imprisoned and after several months of incarceration were released under this short order. It is not known why this order was suddenly issued, or who ordered it (Professor Christian proposes it could have been a forgery), but it undoubtedly saved Aladin from another period of exile or from a more grisly end at the hands of the Bolshevik secret police.

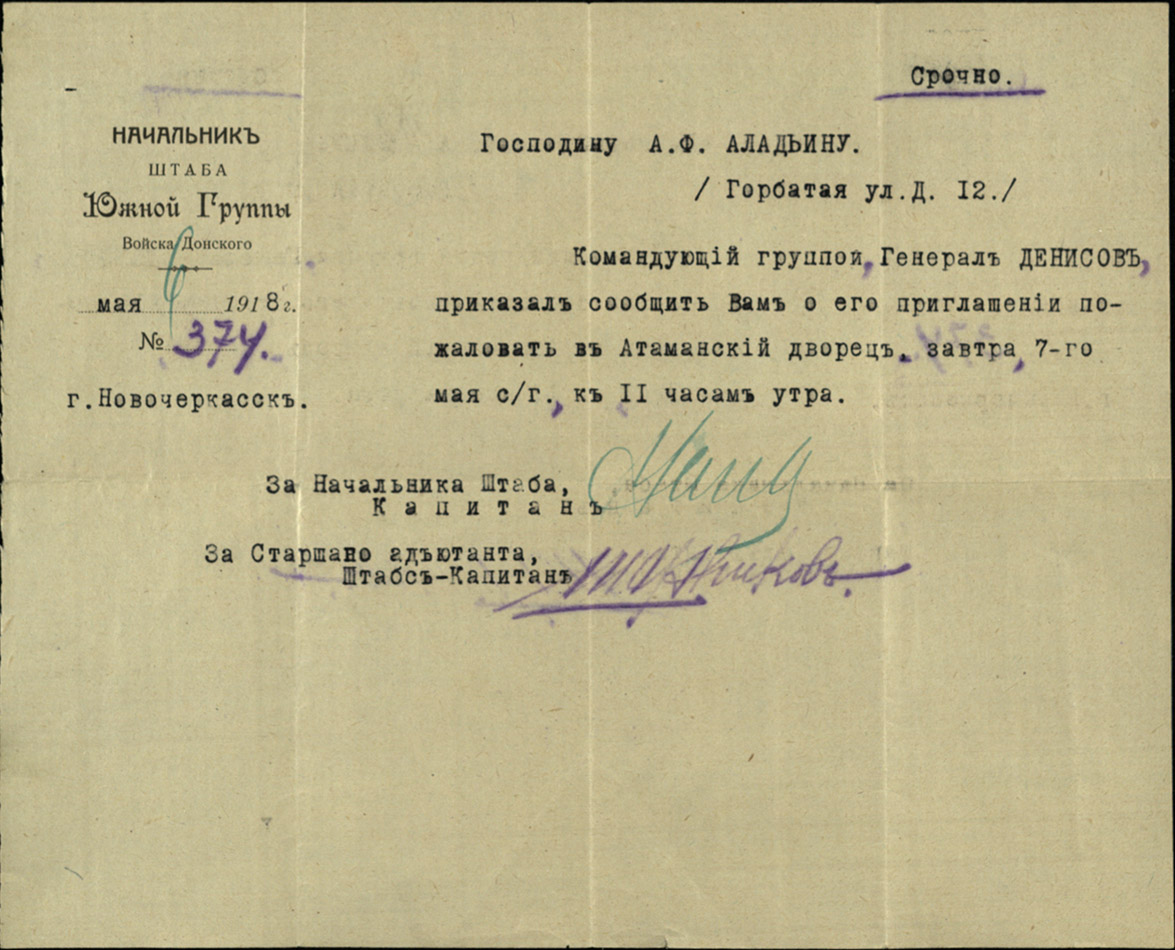

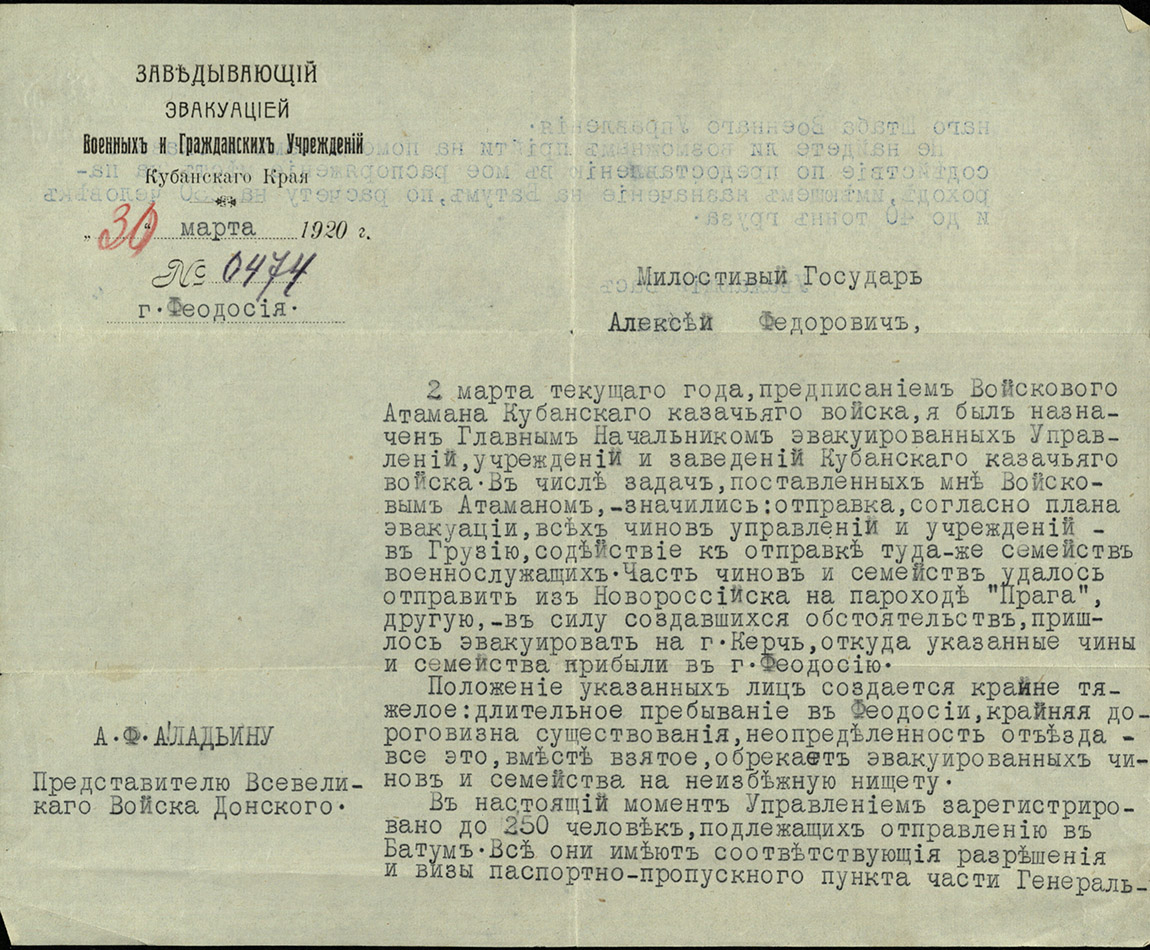

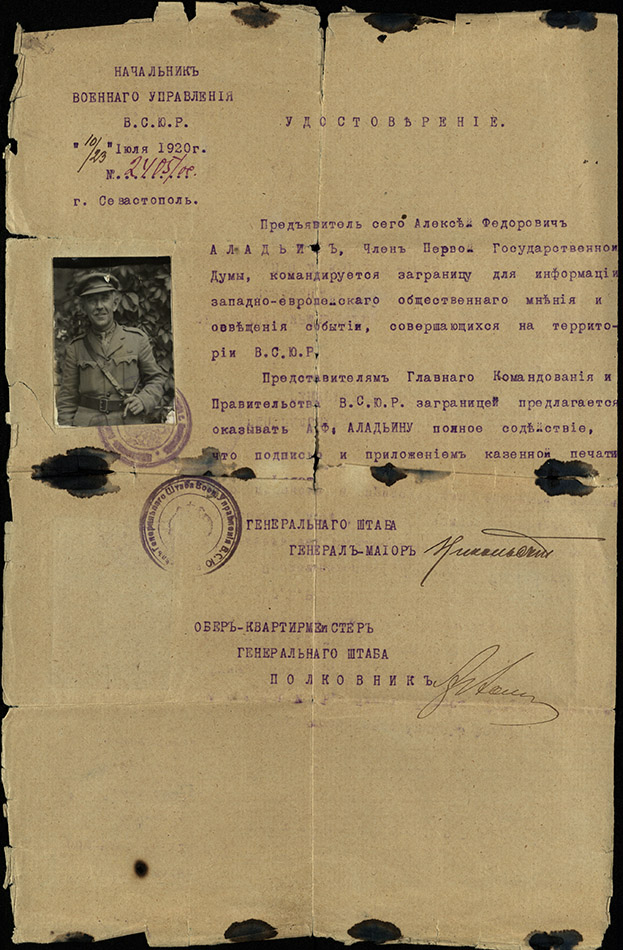

His imprisonment cemented his opposition to the Bolsheviks, and the bulk of the remaining material in this folder relates to Aladin’s time fighting against their Red Army. A multitude of identity certificates and travel permits give some indication as to the atmosphere of distrust that pervaded the country which was torn apart by civil war: one could not move anywhere without permission or confirmation that you were indeed fighting for the right side. His loyalty to Kornilov and seat in the Duma earned him respect amongst the higher echelons of the White Army: he was personally invited to attend the Ataman Palace where the supreme leader of the Cossack army was based, and was charged with helping to conduct several large-scale evacuations of Cossack troops as the Red Army forced them into retreat.

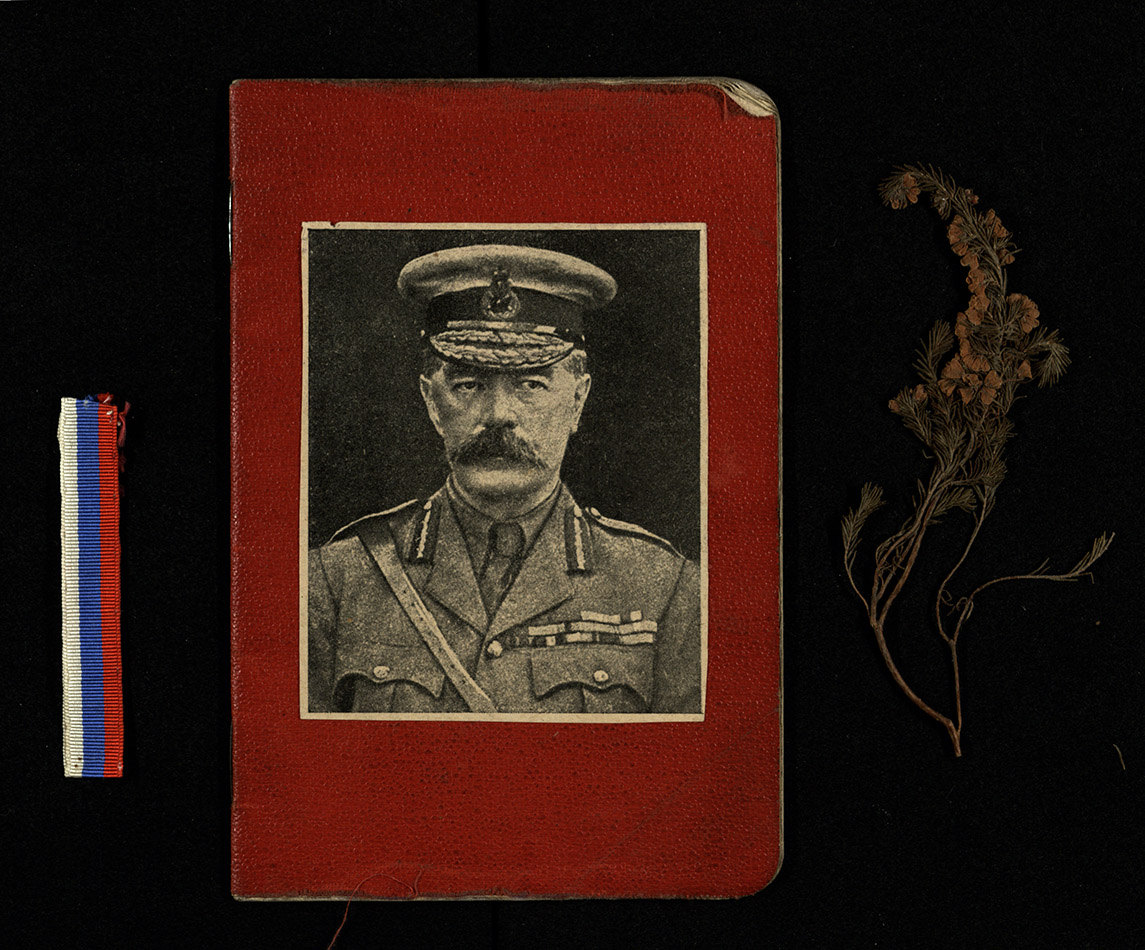

By 1919, Aladin had been placed in charge of the depot for British gifts for the Armed Forces of Southern Russia, and a year later received orders to return to London to carry out a commission on behalf of the White Army. He was issued a foreign passport in March and departed in November. Inside his passport is still tucked a small portrait of Lord Kitchener (whom Aladin greatly admired), a ribbon in the Russian national colours which typically adorned the uniform of soldiers in the White Army, and a pressed flower. Perhaps he kept the ribbon and flower as mementos of a homeland which he was unlikely ever to see again, as a Bolshevik victory appeared increasingly inevitable by the time Aladin embarked for Europe.

Aladin never returned to Russia, remaining in Britain for the rest of his life. He was clearly fond of this country – he spoke fluent English, his closest friend lived here, and he continued to dress in a British officer’s uniform long after his service in the Civil War ended. Indeed, his attachment to Britain caused Trotsky to note derisively in his History of the Russian Revolution that Aladin was a man who “never removed an English pipe from his mouth and therefore considered himself a specialist in international affairs”. In spite of his new home, Aladin’s keen interest in Russian politics endured, and he continued to lecture and write articles on the aftermath of the Revolution until his death in Hampstead in 1927.

It is fascinating to me that such an eventful history can be told in just the seventy two sheets of paper which make up this folder. I was initially surprised that the papers of this Russian revolutionary are here in St Andrews, yet after reflecting on his lonely and lengthy periods of exile, separated from the country in which he was so interested, it seems apt that Aladin’s papers should end up within the archive of the friend who supported him throughout these difficult periods. Having long been interested in Russia in these early years of the twentieth century, I am thrilled that I came across Aladin in our collections, whose captivating story has certainly enhanced my understanding of these tumultuous revolutionary years.

Anabel Farrell

Skills for the Future Trainee

Archives Team

This is so interesting! I just read the book The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk, which is about how Great Britain and Russia fought and maneuvered against each other constantly in the 1800s, and up until the Russian Revolution, so I was surprised to find out about Aladin who apparently loved both countries.

[…] pupils from Cupar’s Bell Baxter High School, who were studying the Russian Revolution (see blog), and her providing transcriptions for the online palaeography self-help tool ReadMe! This is a […]