Claimed from Stationers’ Hall: St Andrews Copyright Music Collection

I first encountered music-loving Principal James Playfair (1738-1819) in University Senate records, when the professors met to discuss library and other matters. Playfair, who combined his professorial duties with being minister of St Leonard’s Church, borrowed copious amounts of music from the library. Playfair Terrace was named after one of the Principal’s many offspring – Provost (later Sir) Hugh Lyon Playfair (1787-1861). Since the terrace was built in the 1840s, nearly three decades after the Reverend Doctor died, there’s no link with the collection of late 18th and early 19th century music now held by St Andrews University Library.

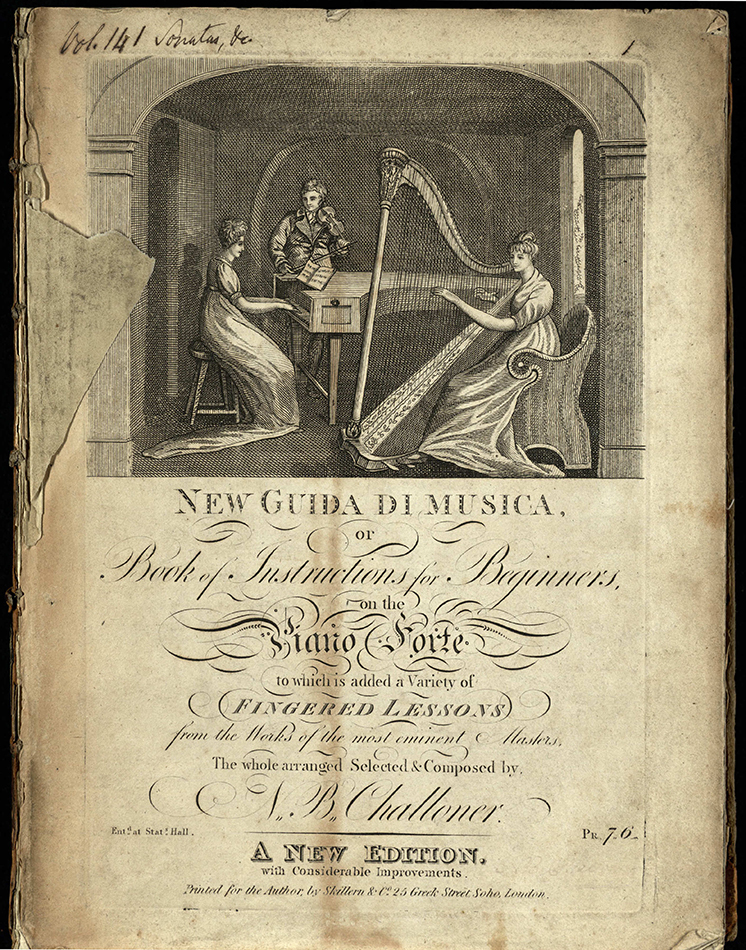

But what was this music that gave the Provost’s father so much pleasure? The story goes back to 1709/10, when the Queen Anne Copyright Act designated nine legal deposit libraries –five were in Scotland, and four of those were the old established university libraries. Once books were registered at Stationers’ Hall in London, the legal deposit libraries were sent (or later, entitled to claim) their copies. In the 1780s, it was finally established that music, maps and prints were also subject to copyright. In the next couple of decades, there was a rush to secure musical copyrights, although some publishers took the attitude that if a title-page said it had been registered, that was good enough. Far more was published than actually registered.

Even when music was registered, copies weren’t always handed in to be sent to the libraries. Moreover, when copies were sent, the libraries didn’t always keep them – some other universities were rather dismissive of the music that they received. (I have ambitions to enlarge my project to examine the whole British picture, but that’s another story for another day.)

However, when the University of St Andrews learned that they could pay to receive lists of all publications registered at Stationers Hall, they requested copies of everything they were entitled to – books and music, arguing that they couldn’t decide if they wanted it until they had inspected it. The inspection was done by a small committee, which decided what to bind immediately, what to postpone, and what would be parcelled up until they got round to it.

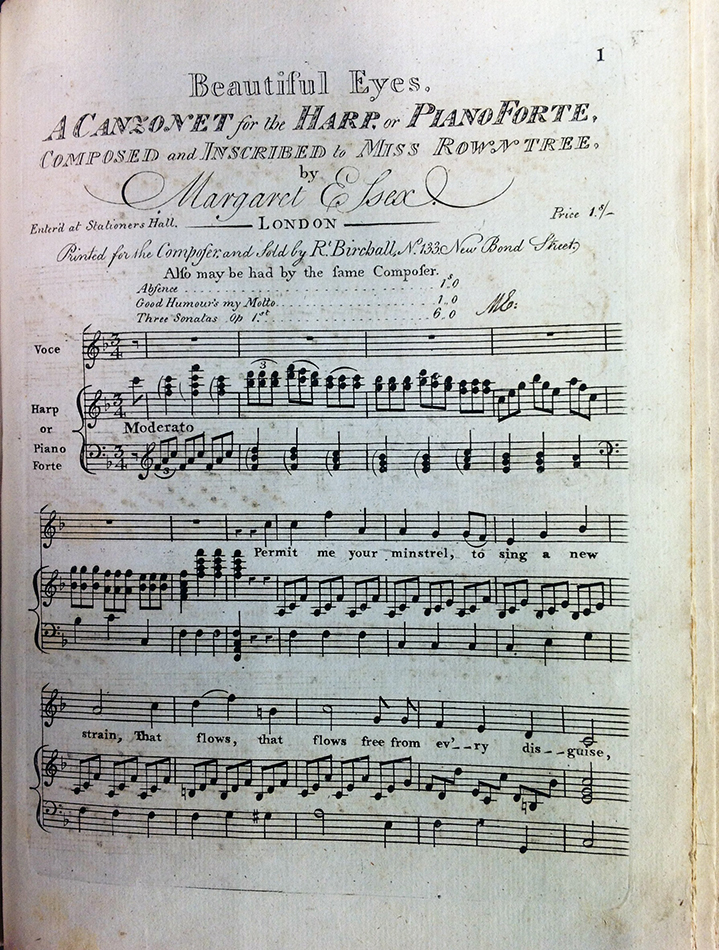

Most of the music dates from the 1790s – 1820s. In 1801, the University had the backlog bound, binding separate instrumental parts in different volumes so that each player would have a book to play from, and roughly sorting the music into categories – for example, books compiling a number of song-sheets, books containing piano variations, or sonatas for piano and one or more solo instruments. Sometimes, didactic material was bound together. One particular volume really interested me, because it collated a number of songs composed by women, along with other songs by men, and including several patriotic songs that would have been published during the Napoleonic Wars. The women’s songs included a couple of the patriotic ones, and others that were sentimental or pastoral in nature. I’m intrigued to think that someone went to the trouble of assembling all this material in one volume. My favourite is ‘Beautiful eyes’, composed by a London governess or music teacher, Margaret Essex in 1801. I’ve recorded it with soprano Dr Jane Pettegree for this blog:-

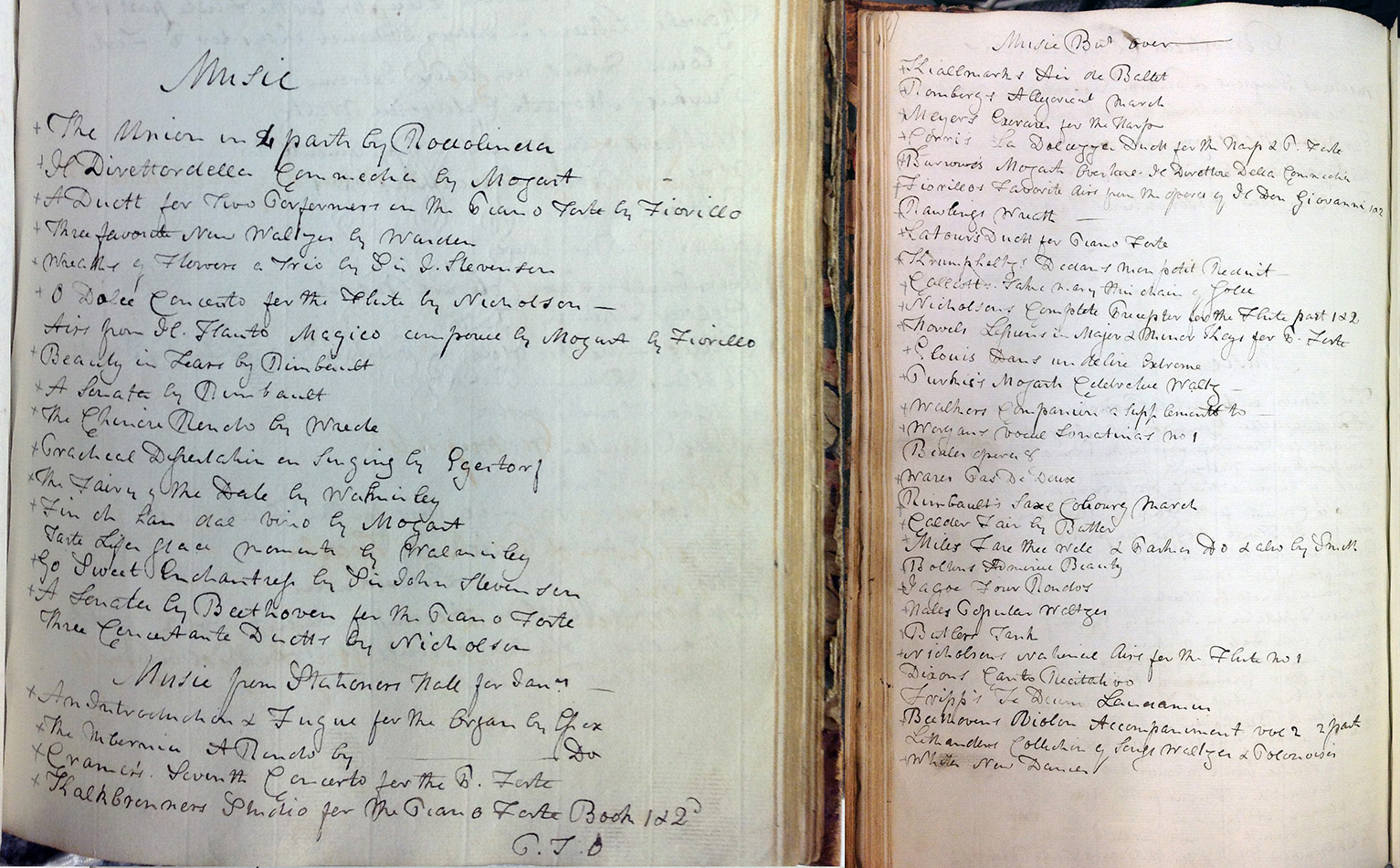

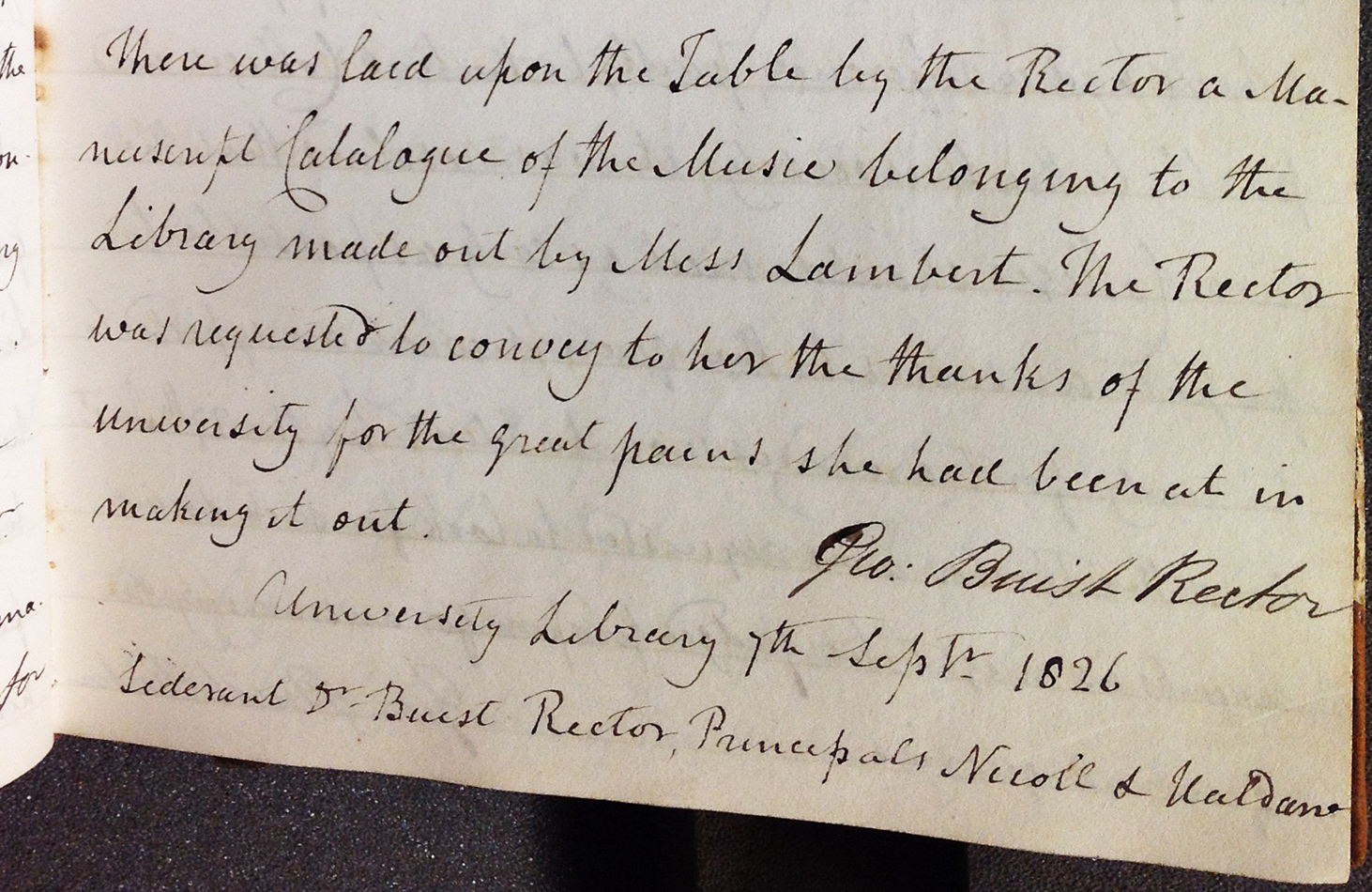

The fascinating thing about the Copyright Music Collection is that – whilst we obviously don’t know what might have been discarded or lost over time – there are still over 400 bound volumes of music. There’s also a contemporary catalogue in two volumes, written by “Miss Lambert”. It was presented at a Senate meeting in 1826, and she received payment that year.

“There was laid upon the Table by the Rector a Manuscript Catalogue of the Music belonging to the Library made out by Miss Lambert. The Rector was requested to convey to her the thanks of the University for the great pains she had been at in making it out. [signed] Geo. Buist Rector.”

The second book wasn’t fully completed until 1836. That year, the legal deposit legislation changed, giving most of the libraries book-funds to replace the free books they’d been claiming under privilege.

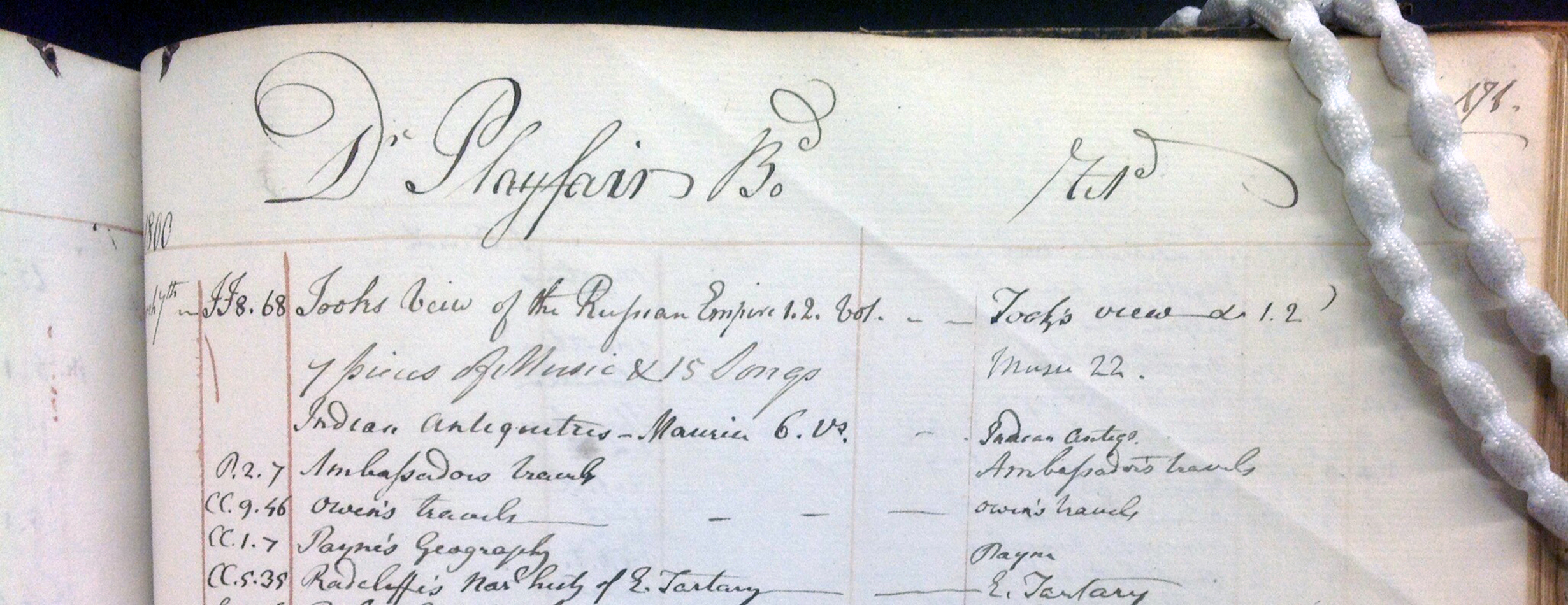

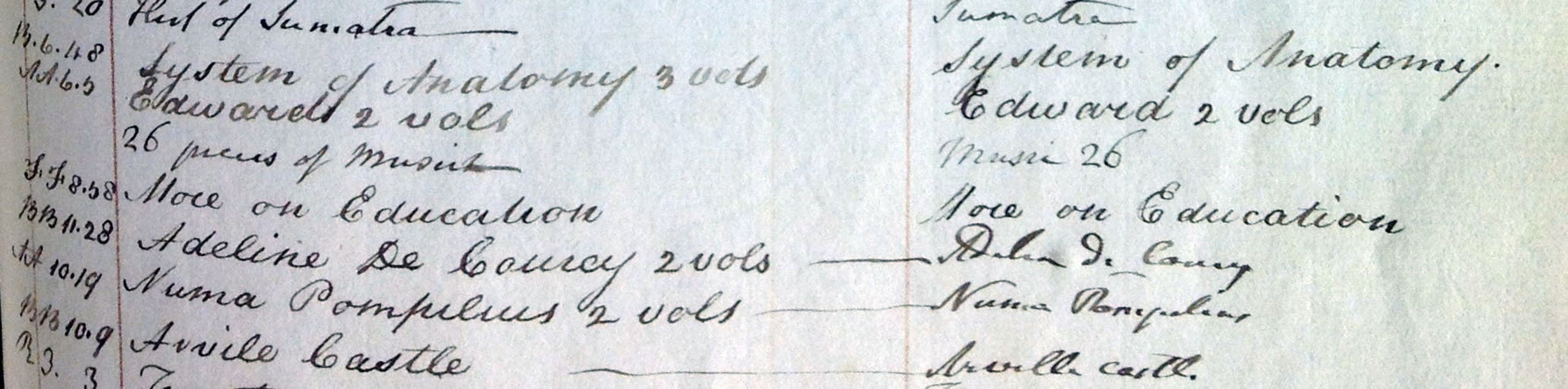

There’s ample documentary evidence that the collection was used heavily by the professors and their friends. Indeed, our friend Principal Playfair borrowed the music before it was even bound – for example, on 7th March 1800, he borrowed “7 pieces of Music & 15 Songs”, and on 26th September that year, “26 pieces of Music”.

From 1801, he borrowed bound volumes, up to ten at a time. Many professors borrowed music regularly for a small coterie of friends (mainly, but not exclusively unmarried women), and their names were entered in the borrowing records. However, Principal Playfair only borrowed for one named lady – a Miss D’Oyley – on a couple of occasions. This does lead us to speculate that his borrowing was mainly for himself and his own large family.

I haven’t yet fully logged the borrowing records to trace which music was most popular, but there are enough instances of national airs being borrowed – especially Thomson’s Scottish collections, Moore’s Irish ones, and settings of Byron’s Hebrew Melodies – to make them pretty certain top of the charts! I’m curious to see what such an analysis will let us conjecture about music-making in the Playfair family. I’m also quite keen to read some of the family journals. Meanwhile, I can’t walk past Playfair Terrace without quietly smiling to myself. For if one thing is certain, this is the terrace named after the Provost who assuredly spent his teenage years surrounded by music!

Dr Karen E McAulay

Music & Academic Services Librarian/ Postdoctoral Researcher

Royal Conservatoire of Scotland

If you’re interested in finding out more, Karen will be participating in a Show and Tell at Martyrs Kirk on Wednesday 28th September at 2pm. The title is, ‘Claimed from Stationers’ Hall: the Surprising Popularity of St Andrews’ Copyright Music Collection in the Late Georgian Era’.

Karen will also be giving an illustrated talk in the University of St Andrews Music Talk series, on 12th October at 2.30pm, featuring performances of more of the women composers’ repertoire – the event is listed at http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/music/listen/events/ .

Our thanks are extended to Dr Jane K Pettegree (Honorary Research Fellow, School of English & Director of Teaching, Department of Music, University of St Andrews), for her willingness to sing the musical example in this blogpost, and her collaboration in the forthcoming music talk this autumn.

[…] Blogpost direct link: Claimed from Stationers’ Hall: St Andrews Copyright Music Collection […]

[…] Blogpost direct link: Claimed from Stationers’ Hall: St Andrews Copyright Music Collection […]

[…] Earlier this year we published a blog post by Dr Karen McAulay of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland about her research using the St Andrews Copyright Music Collection – https://standrewsrarebooks.wordpress.com/2016/08/18/claimed-from-stationers-hall-st-andrews-copyrigh… […]

[…] CLAIMED FROM STATIONERS’ HALL: ST ANDREWS COPYRIGHT MUSIC COLLECTION (18-08-2016) […]

[…] If you have enjoyed this posting, you might also like to read about another Library reader from St Andrews – Professor Playfair and his family. He appears in another article about the Claimed From Stationers’ Hall network, on the Library’s Echoes From the Vault website. […]

If you enjoyed this blogpost, you might also enjoy "A Labour of Love for Miss Lambert", over on the Claimed From Stationers' Hall network website: https://claimedfromstationershall.wordpress.com/2019/11/20/a-labour-of-love-for-miss-lambert/