Historical Cooking, Week 4: Maiden’s Mystery

This week Miriam Buncombe takes on a mysterious recipe from our historical cookbook – the complete manuscript is available for viewing on our Digital Collections Portal

Nestled amongst recipes for vinegar-pickled pressed veal and herb-ginger tripe, the idea of these yeasted almond buns, gently flavoured with aniseed and finished with butter, makes a pleasant change of pace. They sparked curiosity because of its almost appealing flavours, and the technical challenge in following the puzzling instruction to add yeast to a dough made primarily of almond flour (How well would it rise? Would this produce bread or a biscuit?). This recipe also jumps out as it includes a magic ingredient: a few descriptions that might generously be described as measurements. The instructions to add ‘ein oder 2 löffel voll nidlen’ (a spoonful or two of cream) and a ‘einer baumnuβ groβ hebi’ (a walnut-sized piece of [fresh] yeast) were a helpful starting point from which to estimate the measurements for the other ingredients.

However, the thing that appealed the most about these buns were their name, ‘Jungfrawen Schenkelin’. This is one of the few recipes in this cookbook whose title is not a direct description of the dish, such as ‘hard boiled eggs’ or ‘filled pear’. It was perhaps the enthusiasm engendered by this more poetic name – possibly in combination with the relief of escaping from the bewildering plethora of the egg section – that led to an initial misstep in my translation. An early whimsical flight of fancy turned these into ‘virgin’s buns’, taking the ‘Jungfraw’ (virgin or maiden) of the title and the ‘weggli’ (delicious sweet yeasted milk buns known as Weckchen) in the instructions provided on how to shape the dough. However, as these little cakes had actually already been allocated a name in the cookbook, this name was duly translated as ‘maiden’s gifts’, based upon an incorrect reading of ‘Schenkelin’ as ‘(Ge)Schenkelin’, meaning ‘little gift’.

It seemed possible that the ‘Jungfraw’, so out of place in this cookbook, might be a reference to the Virgin Mary. There is, after all, a long tradition of the association of particular foods or pastries with certain feasts of the Church, such as the Weckmänner of St Martins Day. Thus, the virgin of the title of this sweet treat might suggest that these pastries would have been made for a particular Marian feast. Yet no reference was to be found to any Germanic pastries known as maiden’s gift or to any possible link to a feast day. Clearly this was a false turn. Moreover, in various historical German cookbooks such as the anonymous fourteenth-century Buch von Guter Speise, the name Schenkelin or Jungfrawen Schenkelin makes no appearance: another dead end.

However, finally stripping away all the extras and false leads, a positive result was at last stumbled upon. The eponymous Schenkelin were not ‘Geschenke’ (gifts) but rather ‘Schenkel’ (thighs). ‘Schenkeli’, it turns out, are a deep-fried speciality made primarily in Switzerland during Karnival, which are still made to this day (if to a somewhat different recipe). That said, the ‘maiden’ part of the name now seems to have dropped from the title without a trace, but when or why remains a mystery. Thus, coming almost full circle, these historical delights might therefore be known by the slightly eyebrow-raising moniker of ‘maiden’s thighs’. So, it turns out that the initial whimsy of virgin’s buns wasn’t so far off after all.

Maiden’s Thighs:

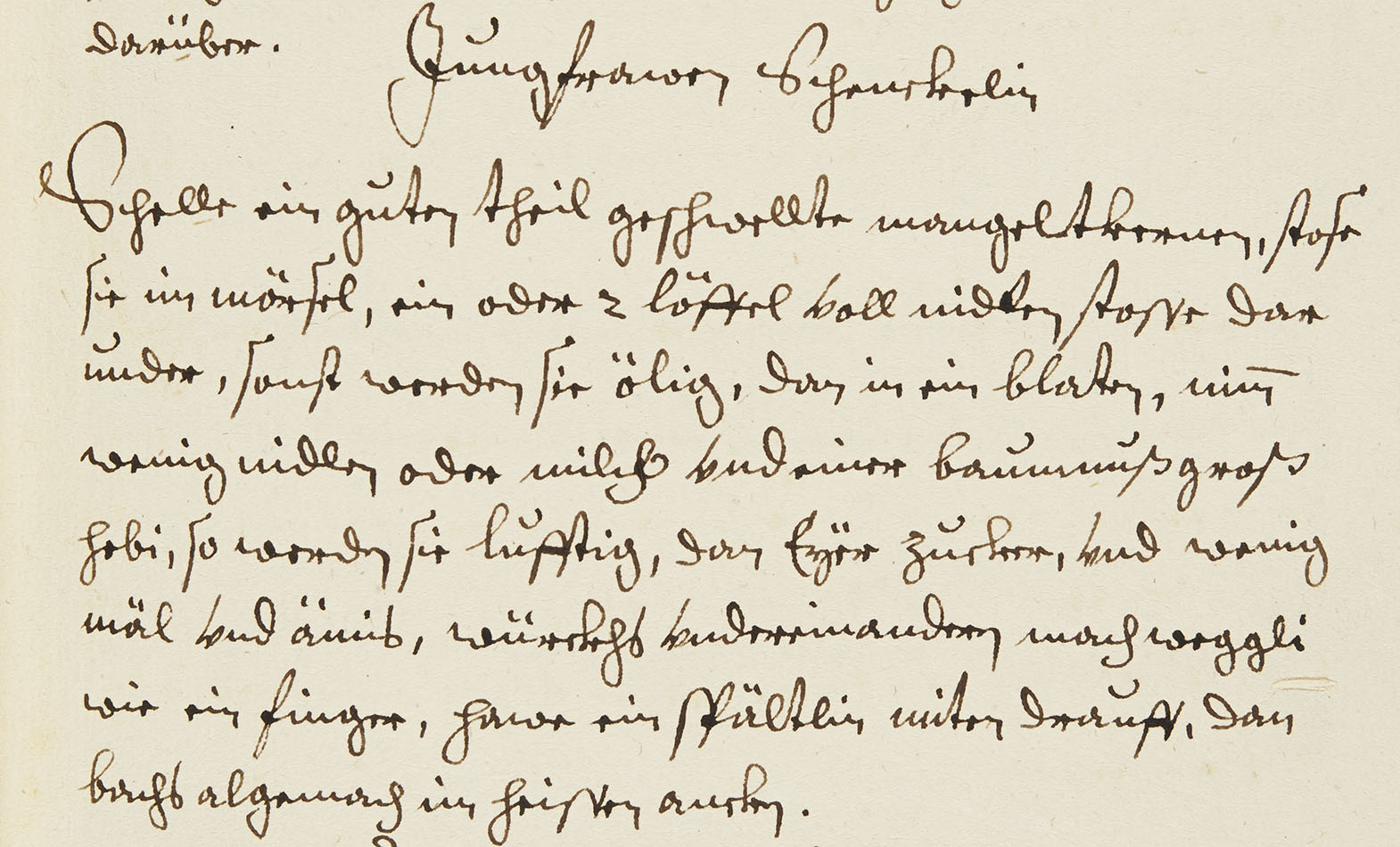

Shelle ein guten theil geshwellte mangeltkernen, stose sie in mörsel, ein oder 2 löffel voll nidlen stosse dar under, sonst warden sie ölig, dan in ein blaten, nim wenig nidlen oder milch vnd einer baumnuβ groβ hebi, so warden sie lufftig, dan eyer zucker, vnd wenig mäl vnd äniβ, würckhβ vndereinanderen mach weggli wie ein finger, hawe ein pfältlein miten drauff, dan bachβ algemach im heissen ancken.

Shell a number of soaked almonds, cut into pieces, add one or 2 spoons of cream, lest they become oily, then put in a bowl with a little cream or milk and a walnut-sized piece of [yeast], so they are light, then [add] eggs, sugar, and a little flour and aniseed, mix together then make finger shaped buns, cut a crease in the middle, then bake in hot butter.

First, two tablespoons of cream were mixed with 150g (pre-ground) almonds as per the recipe, so that the nuts did not become oily. Such oiliness did not really seem to be an issue, but the cream was added nonetheless. Next, 100 g strong bread flour, 40 g sugar, two star-anise (having been toasted and ground) and 10 g fresh yeast were mixed into the almonds. Then an egg and approximately 75 ml milk were added, and the mix was beaten thoroughly to make a wet, sticky batter.

The description of the cakes as ‘weggli’ made them seem reminiscent of an enriched, sweetened dough, thus strong bread flour was used, and the combined mix was left expectantly to rise for two hours. A big flop – as far as could be observed, there was no discernible difference in size after this proving time. It was clear that fluffy, light, sticky almond buns were not to be. Still, moving swiftly on to the recipe’s subsequent direction to make finger-shaped buns, 14 walnut-sized balls of the dough were crafted into sausage-shaped biscuits using floured hands, then a ‘pfältlein’ or crease was made along the centre of each bun using a floured knife.

The recipe then offered up the instruction to bake in hot butter – most confusing to modern cooks. Unclear as to whether the recipe envisaged these cakes as baked or fried, the version which seemed to present the highest chance of the buns being cooked through was chosen. After brushing them with melted butter, they were baked in the oven at 180oC for 12 minutes. Success! The buns may have looked a little misshapen and grey, but they had finally doubled in size and the taste was oddly moreish: semi-fluffy, just slightly sweet and with just a hint of aniseed. As they were, they worked quite well as a breakfast bun alongside coffee as they were not overly sweet, however for those with a sweet tooth, the sugar could easily be increased.

Modern schenkeli recipes have less almond flour or omit it altogether, flavouring them with vanilla, lemon or cinnamon rather than star anise, and tend to call for the buns to be fried. For completeness sake, the second possibility of the bake in hot butter instruction is attempted, and a second batch of buns – otherwise made to the same recipe – is fried in butter. The verdict: charcoal on the outside, raw on the inside. Baking is the clear winner for these delicious almond buns!

Miriam Buncombe

Special Collections Volunteer

Fascinating subject …. I wonder if the maiden's thighs have any cultural relationship to Fatima's Fingers?

Thanks for your comment James - we aren't sure if Fatima's Fingers are related - we'd be glad to know if anyone can find out!