Remembering those lost in times of war, Christmas 1916

Full of old memories she yet shall be

Nurse of heroic men for whom the debt

To that dim past is unacknowledged yet,

Till Time shall set their names in history.

From St Andrews by W L Courtney

Just as 2016 has been a year of shocks and reversals, atrocities and hard-to-believe events, so was 1916, with the calamity of the Battle of the Somme – over one million killed or injured in 5 months of endless brutality. Christmas that year would not be a celebration but a time to remember and mourn. Almost everyone would have known of someone lost in the conflict. As we reflect upon a year that has not gone to plan, so would they. They knew now it was not going to be over by Christmas 1914 and the spirit which had brought the first year’s Christmas ceasefire and football game in no man’s land was gone. The Somme had plunged the world into the bloodiest battle ever, with almost 60,000 British casualties on the first day alone. No one could have imagined slaughter on this scale. Nothing in the war so far had prepared them for this.

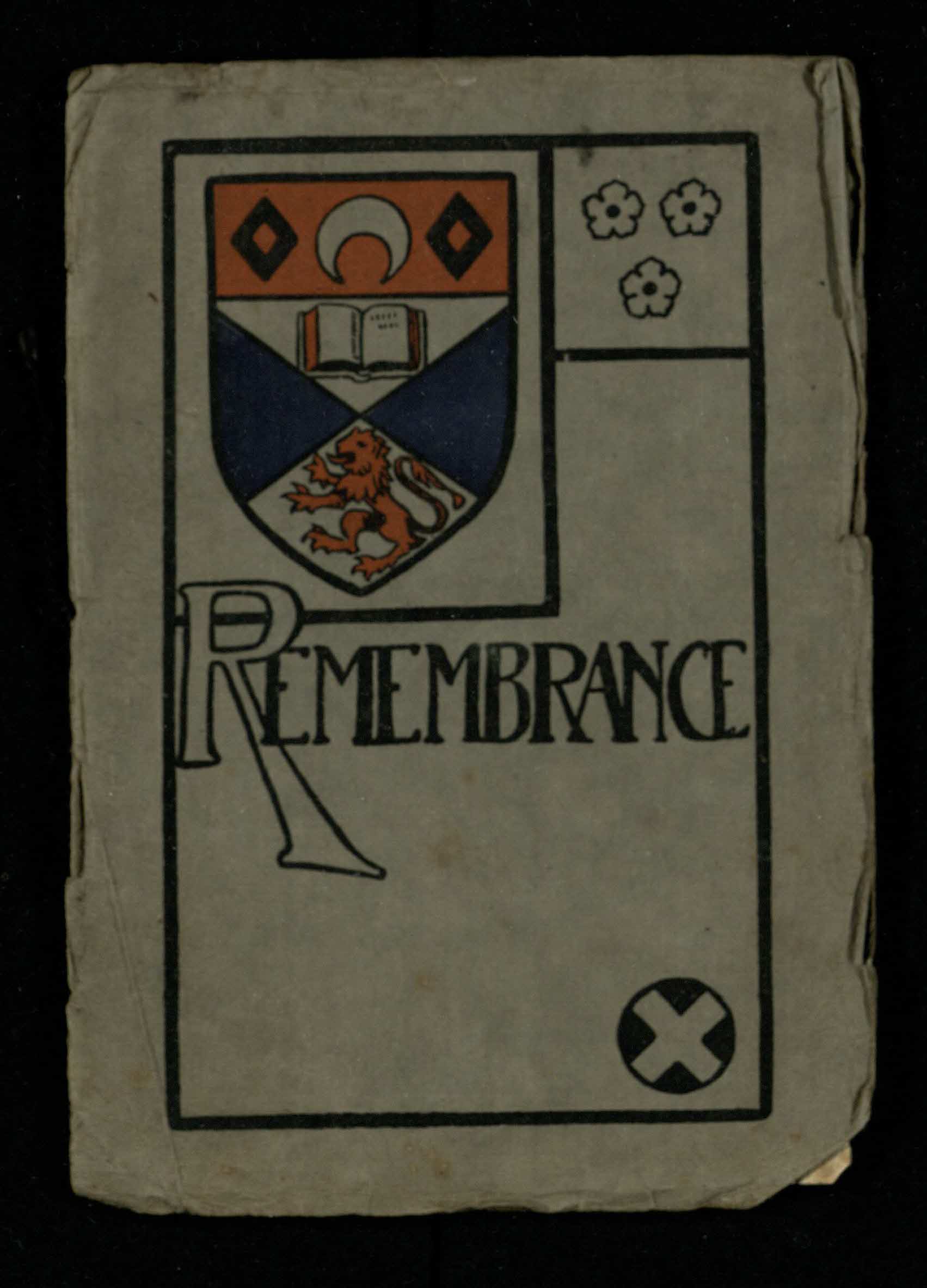

This short pamphlet called Remembrance was produced for Christmas 1916 by Mrs Herkless, wife of Principal John Herkless, and the ladies of the University. They had brought out a similar booklet in 1915, featuring poems by alumni Andrew Lang and R F Murray, about the University and the town (UYUY37781/F/4). That was for Christmas cheer. This one surely was influenced by the losses of the Somme which had removed the flower of the officer class of England and Scotland, as well as all those ordinary men. Although written for different occasions, the poems fit well with thoughts of heroism, duty, loss, remembrance, in the lines at the start by William Courtney and these from ΑΙΕΝ ΑΡΙΣΤΕΥΕΙΝ by RF Murray:

To lead

In whatsoever things are true;

Not stand among the halting crew

The faint of heart, the feeble-kneed

Who tarry for a certain sign

To make them follow with the rest.“The fire of striving in thy breast,

Shalt win, although the race be long.

Not much is known about Principal Herkless as he left very few personal or official records. He is seen as something of a caretaker principal, holding office from 1915 to 1920, moving into the post after the death of Principal Sir James Donaldson at an uncertain time of war. There is even less known about his wife and how the ladies got up the idea of these booklets. I have found two but there may have been more, perhaps a fundraiser for good works during the war. The idea of using poetry from St Andrews alumni was a good one, something to send out to graduates at the front to remind them of happier days.

You can read the full text of these two pamphlets here:

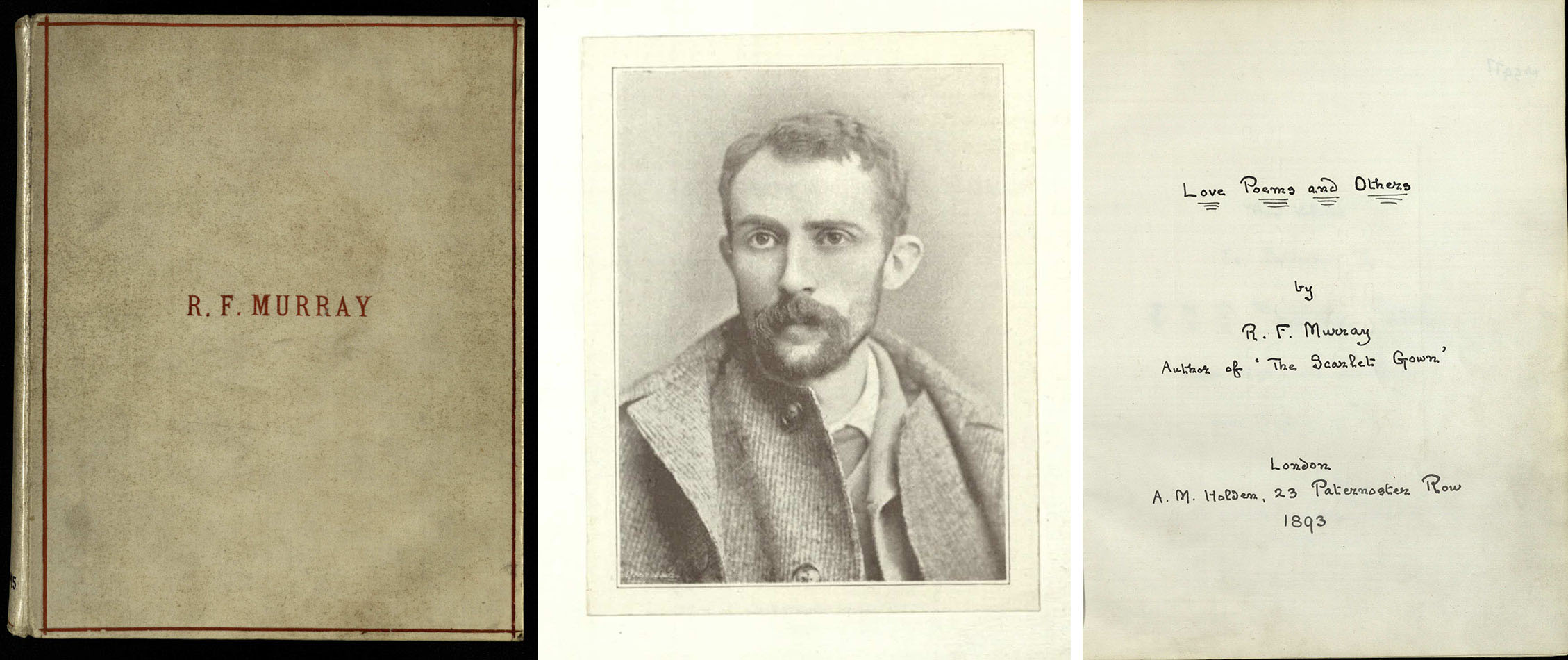

Robert Fuller Murray (1863-1894) came on a scholarship to St Andrews in 1881, and had stayed on as a research fellow to Professor Meiklejohn. He produced two volumes of poetry but died very young of TB in 1894. As well as The scarlet gown; being verses by a St Andrews man, 1891 we have a beautiful volume of poetry handwritten by Murray, later edited and published by Lang after Fuller’s death as Robert F. Murray (author of the Scarlet Gown), his poems; with a memoir by Andrew Lang (msPR5101.M5 [ms5477]). There is also St Andrews Student Songbook: A Selection of Songs from the Scarlet Gown by R.F. Murray set to music by John Farmer (ms36998).

William Leonard Courtney (1850-1928), was a writer and editor, mainly of the Fortnightly Review, who corresponded with Andrew Lang and was awarded an honorary LLD from St Andrews in 1885.

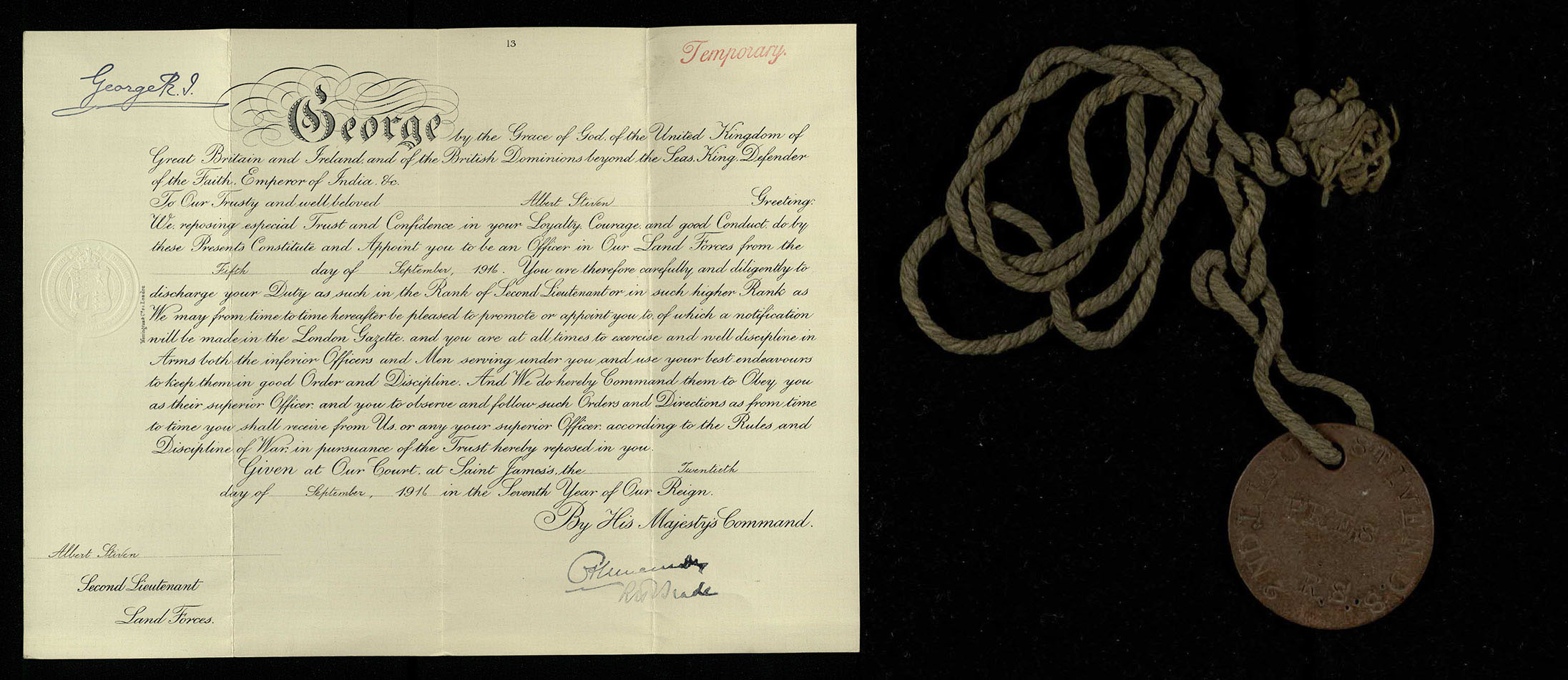

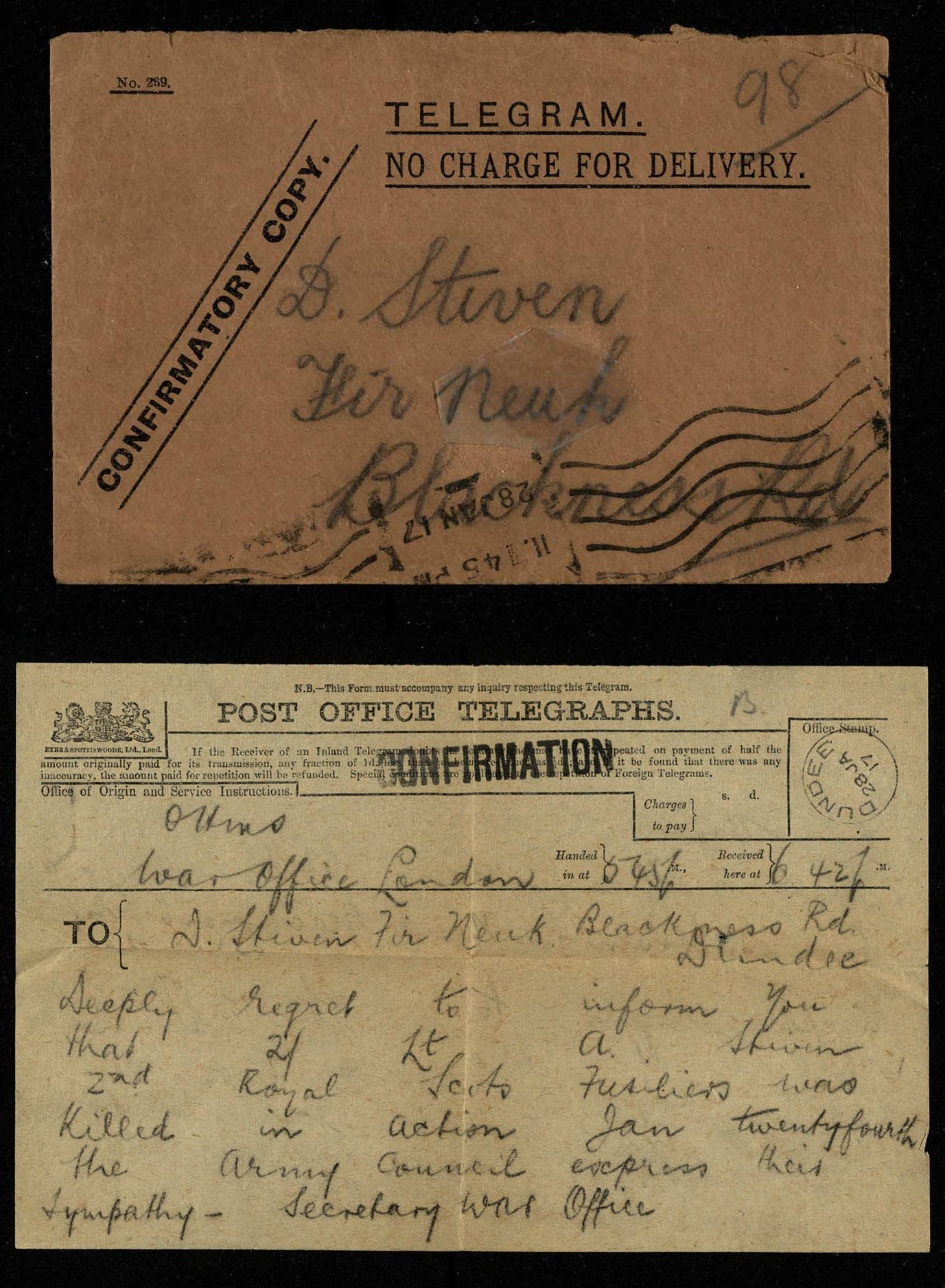

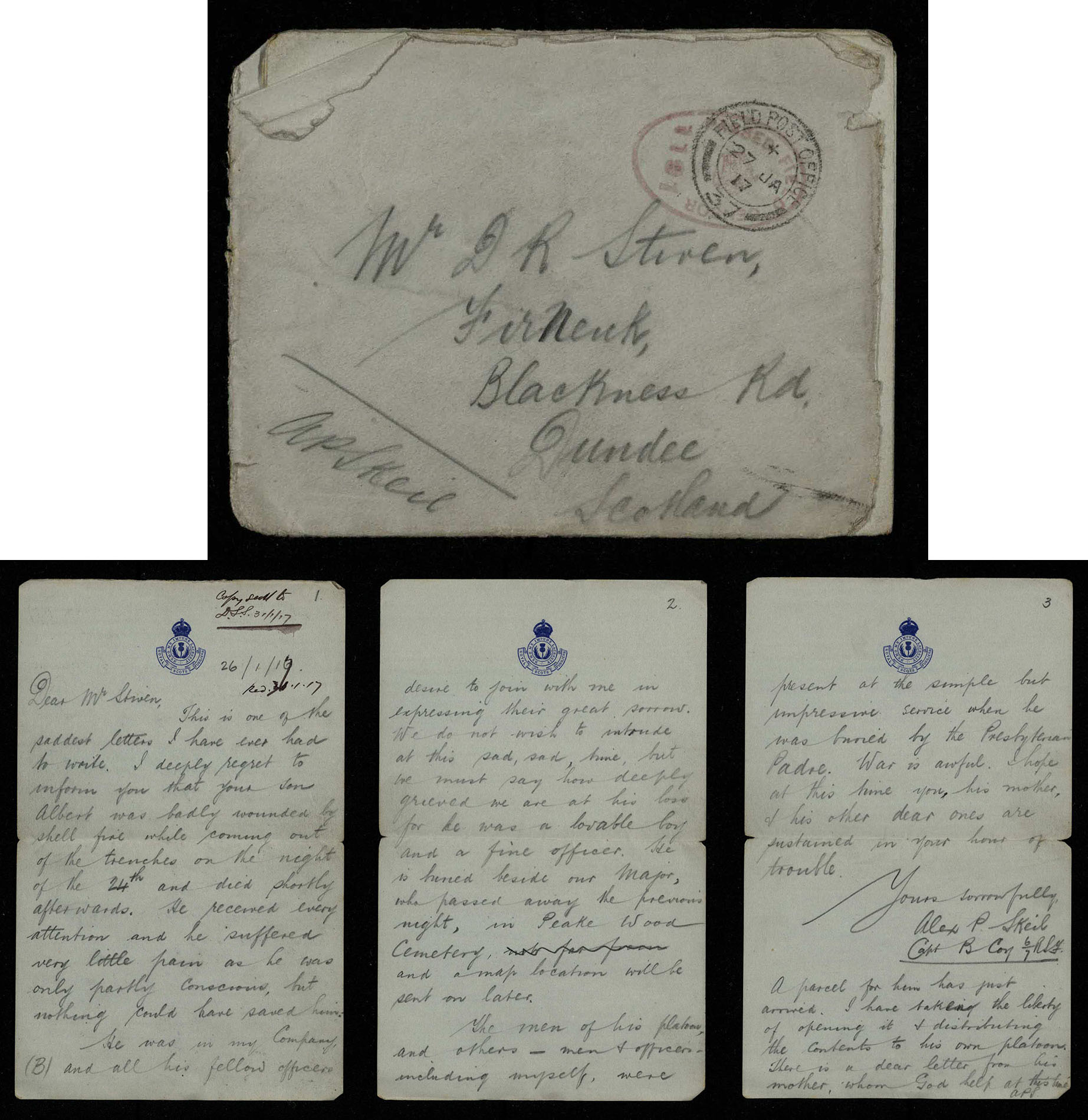

But without its human story of grief and loss, it is just a book of pleasant poems. I came across Remembrance in the papers of David Sime Stiven, kindly gifted to us by the Stiven family recently. He was a St Andrews graduate in divinity and minister in the Church of Scotland. But in 1916 he was in the Royal Scots Regiment at the front in France and his brother Albert was fighting with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. Both were away at Christmas, and soon after, on 26th January 1917, Albert was killed in action. Perhaps that’s why this book had such resonance that his brother kept it all his life.

There are letters from Albert, always positive and cheerful, then letters about his death from his brother, their father, and his commanding officer, which show how important this young man was to his family and friends, and what a great loss his death was to them.

The brothers were sons of David Russell Stiven (1859-1924), manager of the Blackness Foundry and later Consulting, Inspecting, Mechanical Engineer and Valuator in Dundee, and Jane (Jeannie) Sime (1855-1938). David was the elder by a year, born in 1896, and went up to St Andrews in 1913, but volunteered for active service in 1914. He served in Egypt with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, 1915-1916, and then in France, 1916-1918. Albert volunteered too. He started training camp in April 1916, and was sent to the front in November that year, just missing the Somme.

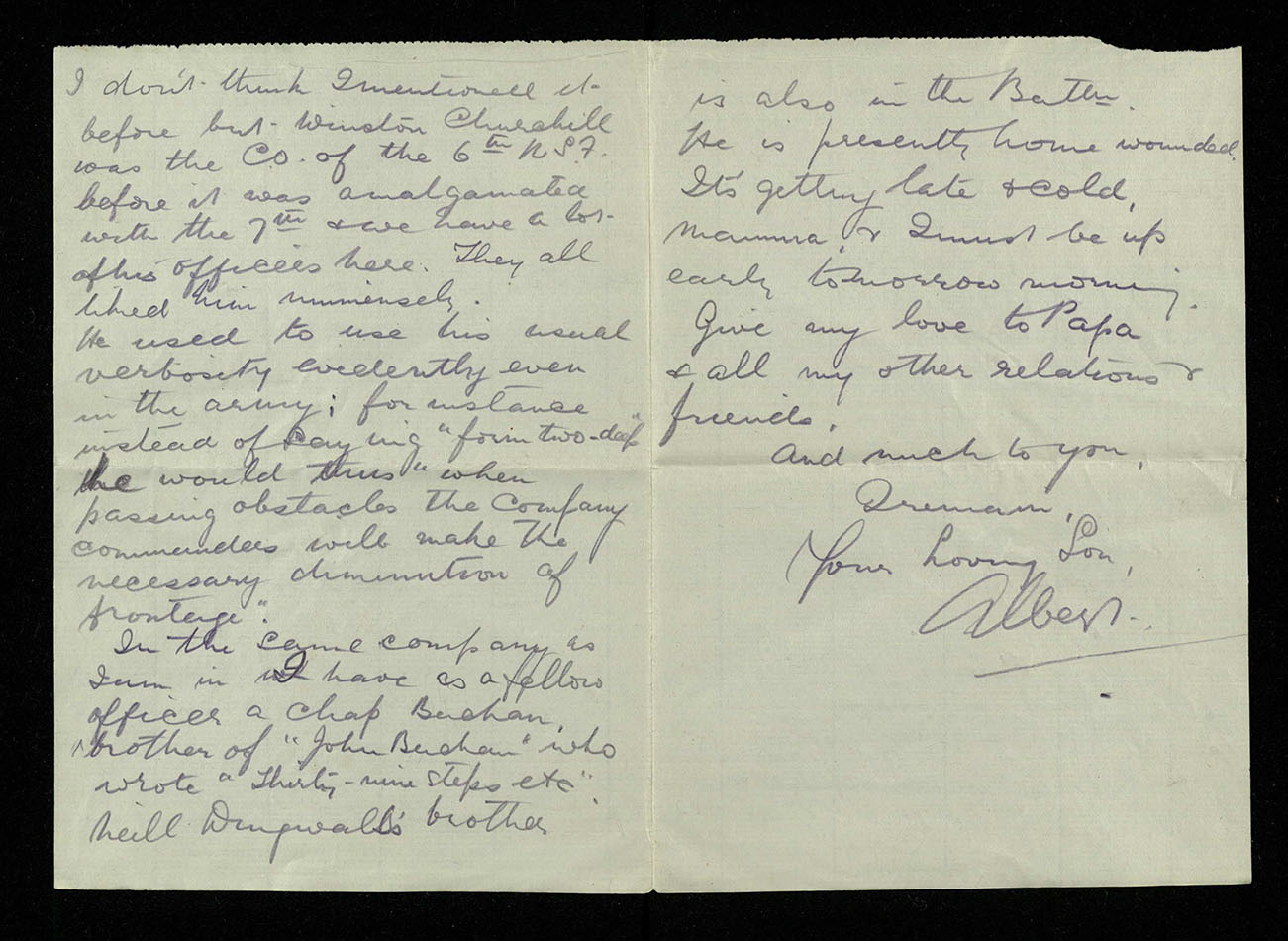

Albert’s letters are full of stories, like the one about Winston Churchill, or about the enraged French Madame, with requests for items to be sent out, “The most relished thing the Chaps get here is butter, the Army butter is so rotten”, or “a loaf or two of Hovis bread”; he says little about the war.

I don’t think I mentioned it before but Winston Churchill was the CO. of the 6th NSF before it was amalgamated with the 7th & we have a lot of his officers here. They all liked him immensely. He used to use his usual verbosity even in the army; for instance instead of saying “form two-deep” he would thus “when passing obstacles the company commander will make the necessary diminution of frontage”.

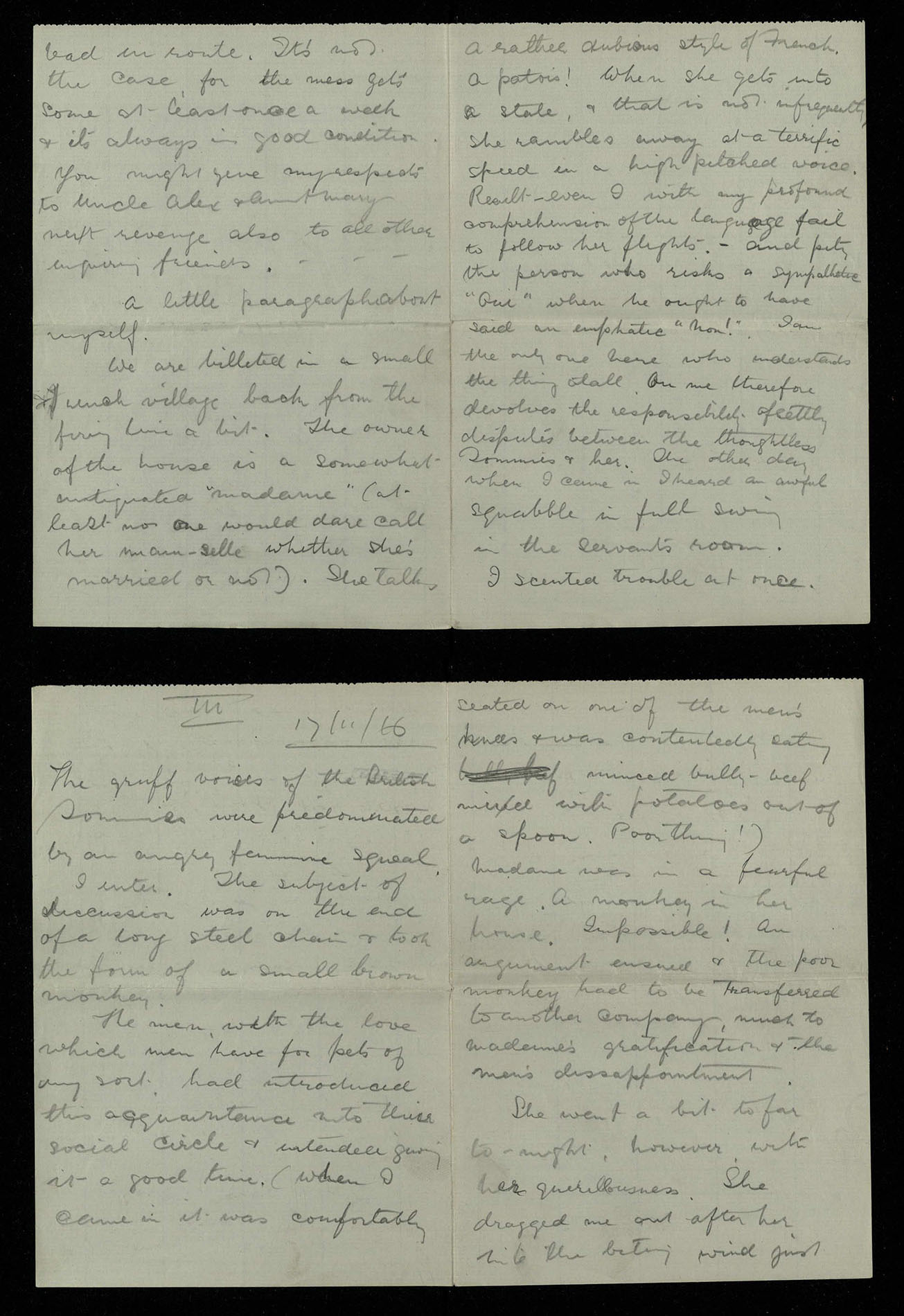

“We are billeted in a small French village back from the firing line a bit. The owner of the house is a somewhat antiquated “Madame” (at least no one would dare call her mam-selle whether she’s married or not). She talks a rather dubious style of French a patois!….pity the person who risks a sympathetic “Oui” when he ought to have said an emphatic “Non!” I am the only one who understands the thing at all. On me therefore devolved the responsibility of settling disputes between the thoughtless Tommies and her.

He has to intervene when the soldiers find themselves a pet monkey.

Madame was in a fearful rage. A monkey in her house. Impossible!” The monkey had to be transferred to another company.

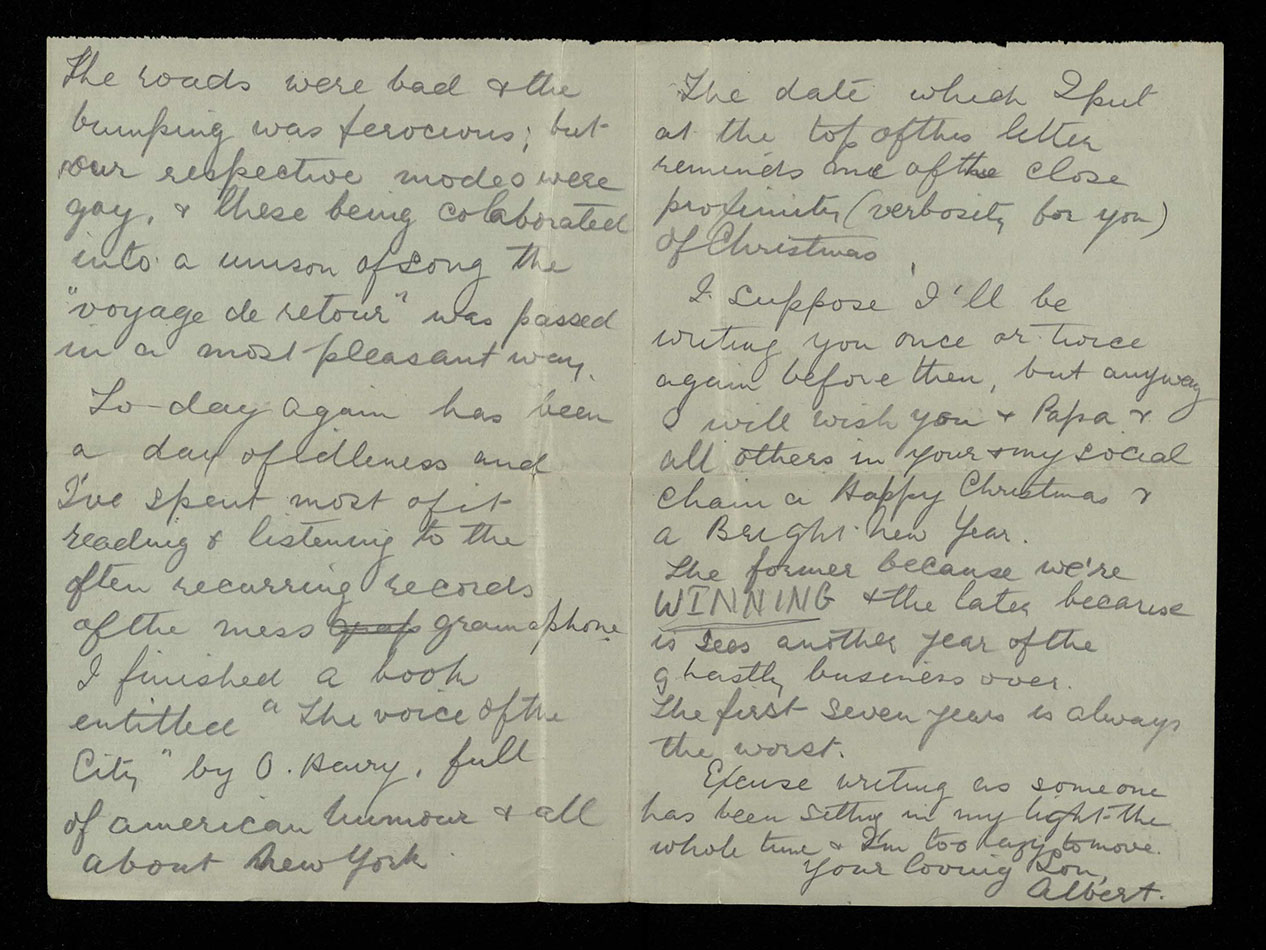

He sends Christmas wishes and thinks the war will be over soon as they were WINNING!

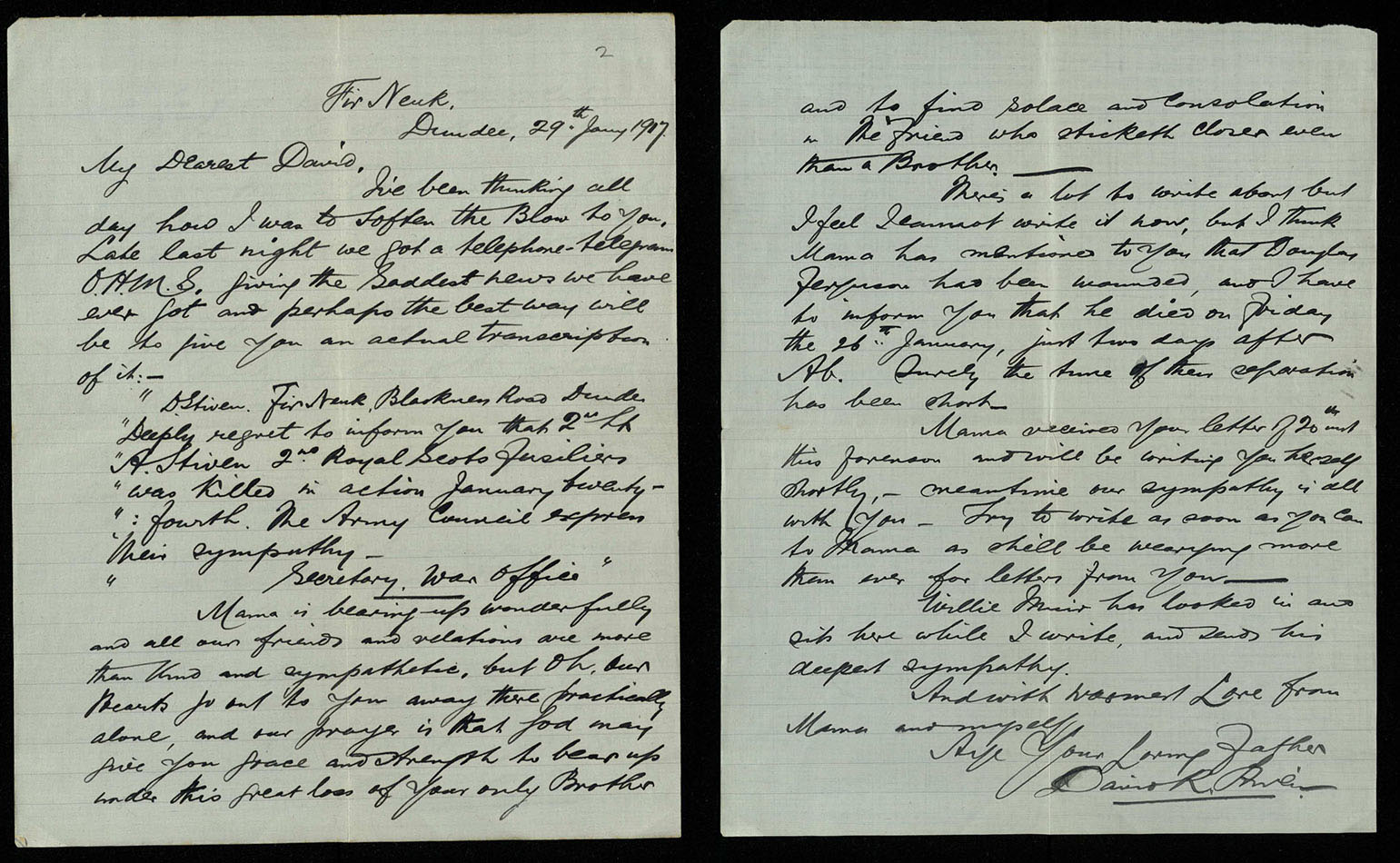

Albert is full of life and fun. Then he was gone. The letters from his CO to his father and from father to son are heart-breaking.

‘We must say how deeply grieved we are at his loss for he was a loveable boy and a fine officer’.

‘I’ve been thinking all day how to soften the blow to you. Late last night we got a telephone-telegram OHMS giving the saddest news we have ever got.”

Albert was buried in Peake Wood Cemetery, Fricourt, near the Somme. The letter talks of the simple but impressive service by the Presbyterian Padre.

David Stiven returned to St Andrews after the war, graduating with an M.A. in 1919 and B.D. in 1922, gaining the Berry Scholarship. He went on to a long career in the Church of Scotland, but never got rid of this little book. It symbolised his missing brother who went cheerfully to war and never returned.

Maia Sheridan

Manuscripts Archivist

[…] via Remembering those lost in times of war, Christmas 1916 — Echoes from the Vault […]

[…] called Remembrance produced for Christmas 1916 by Mrs Herkless, wife of Principal John Herkless, and the ladies of the […]