150th anniversary of John Stuart Mill’s rectorial address

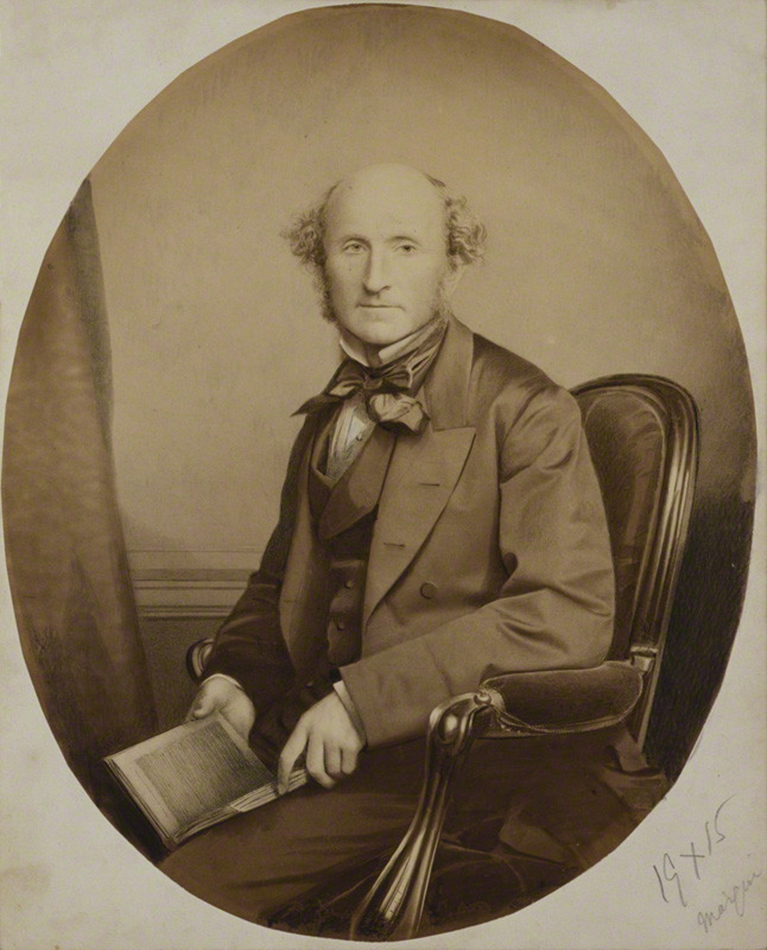

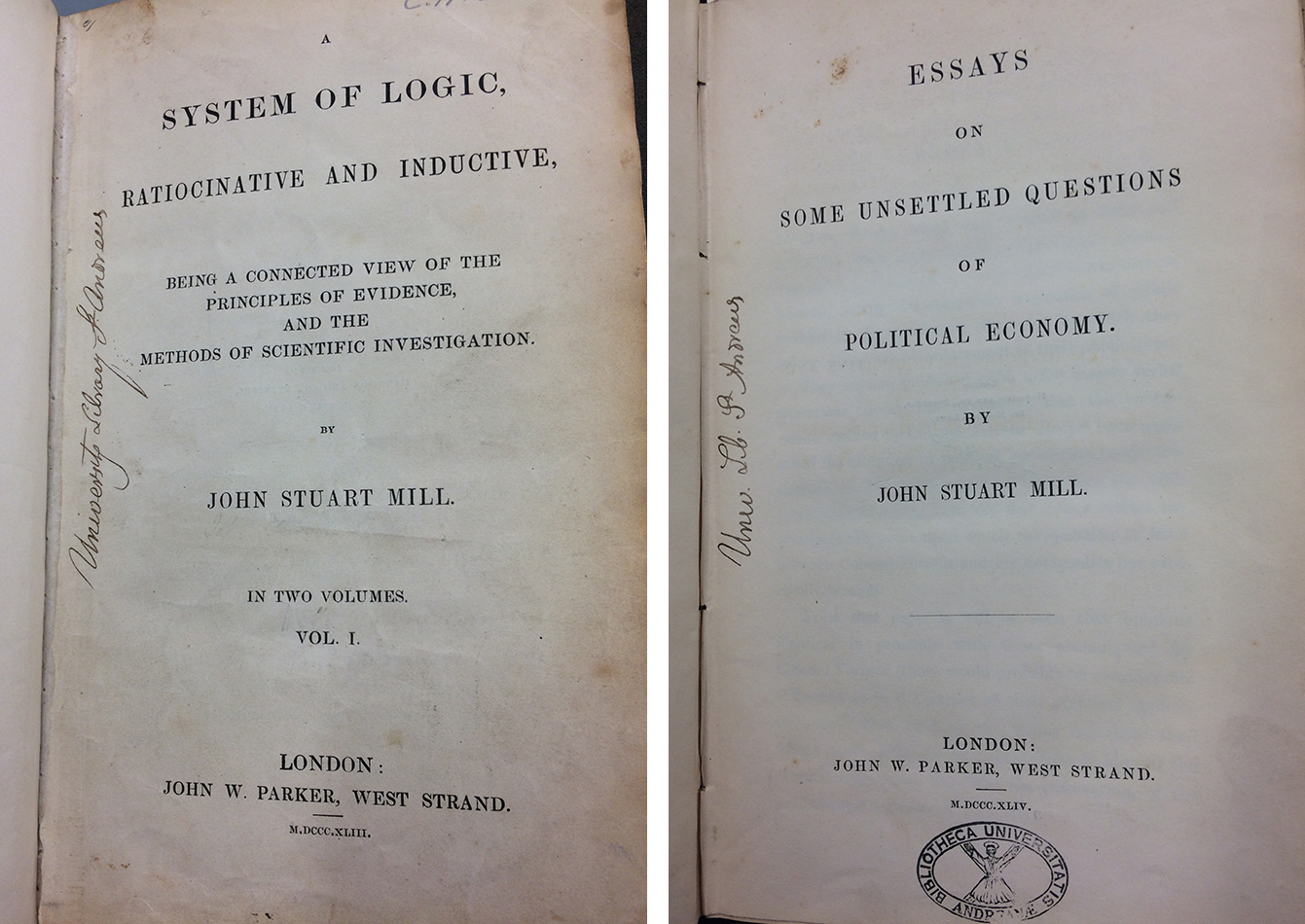

John Stuart Mill, arguably the most important British philosopher of the 19th century, and principal architect of philosophical utilitarianism, was elected Rector of the University of St Andrews by its students, holding office from 1865 to 1868. He gave his inaugural address on 1 February 1867. In commemoration and celebration, on Friday 3 February 2017 a public lecture will be given by Professor Helen Small of the University of Oxford, entitled ‘The Liberal University and its Enemies’. The current Rector, Catherine Stihler MEP, will respond and the Principal will preside. We have explored the Library’s rare books and the University’s archive to find out more about Mill as Rector.

The rectorial election of 1865 was only the third after the role of Rector had been redefined under the Universities (Scotland) Act of 1858. The opportunity was still there under the Act for a Rector to fulfil the vision of those behind the reform, and to develop the Rector’s role as Chair of Court to become pivotal to the daily administration of the University. However, Mill’s interpretation and practice of a more honorary role led to a focus on the ceremonial, leaving the way open for role of Principal to evolve as the focal point of the administration of the University.

The first of the ‘ornamental’ Rectors”

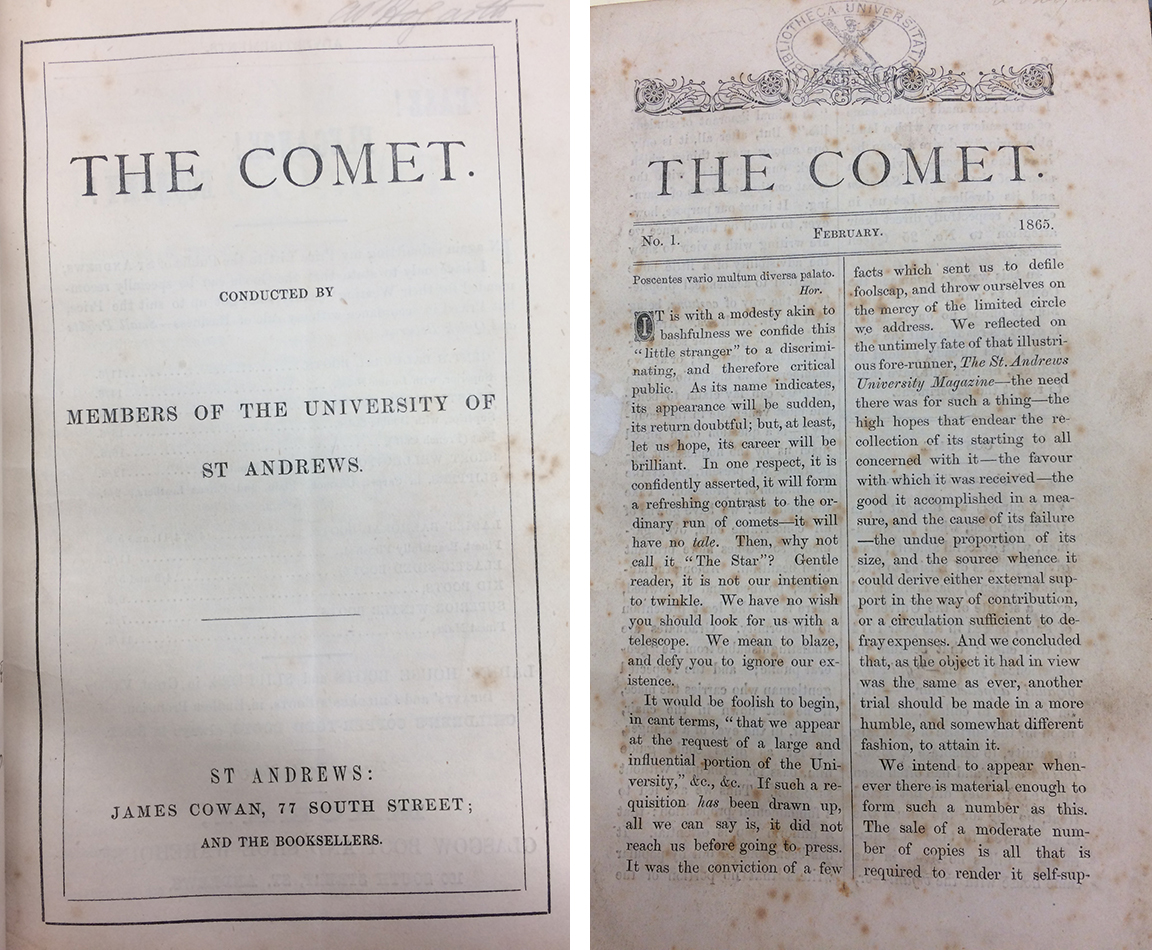

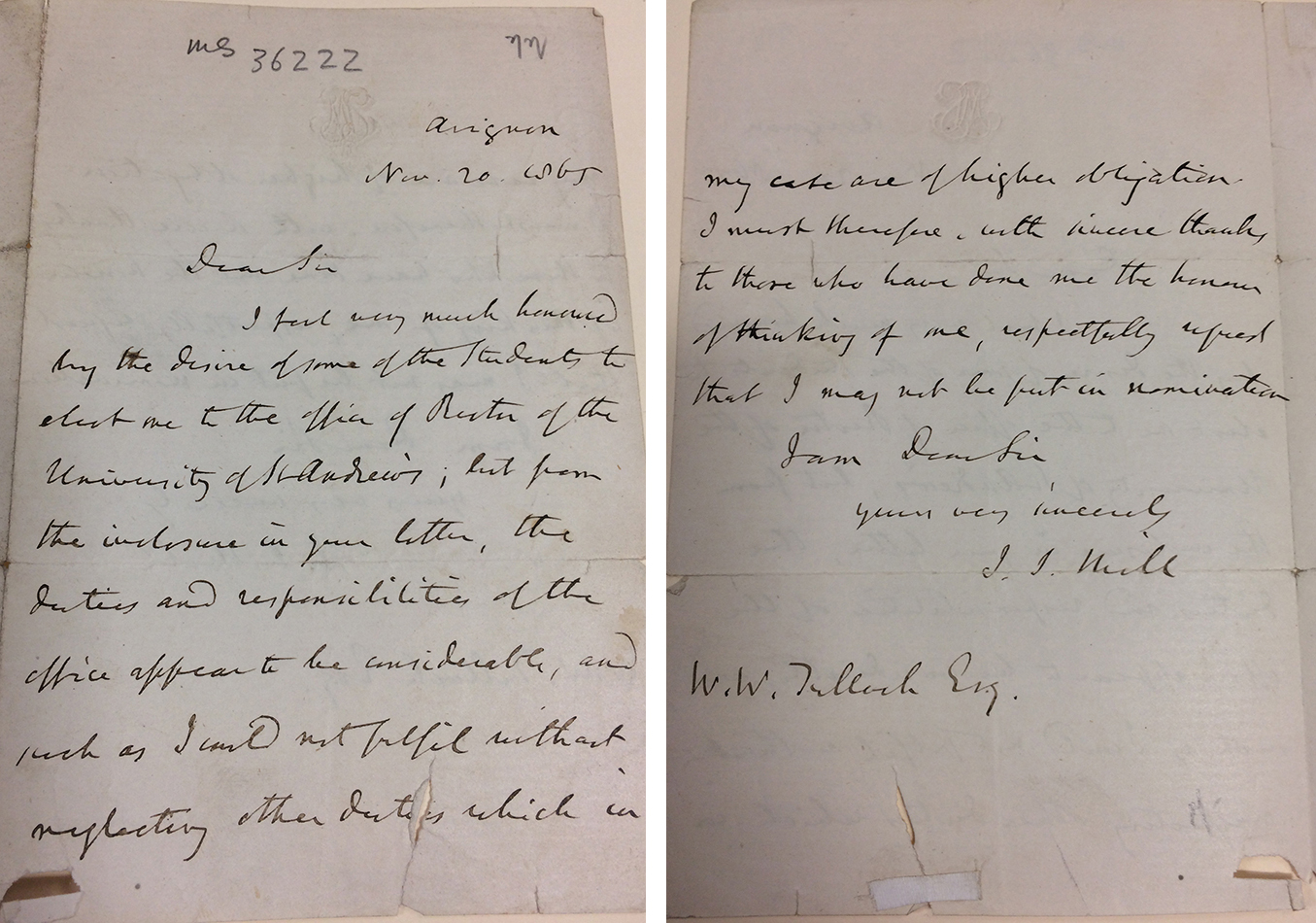

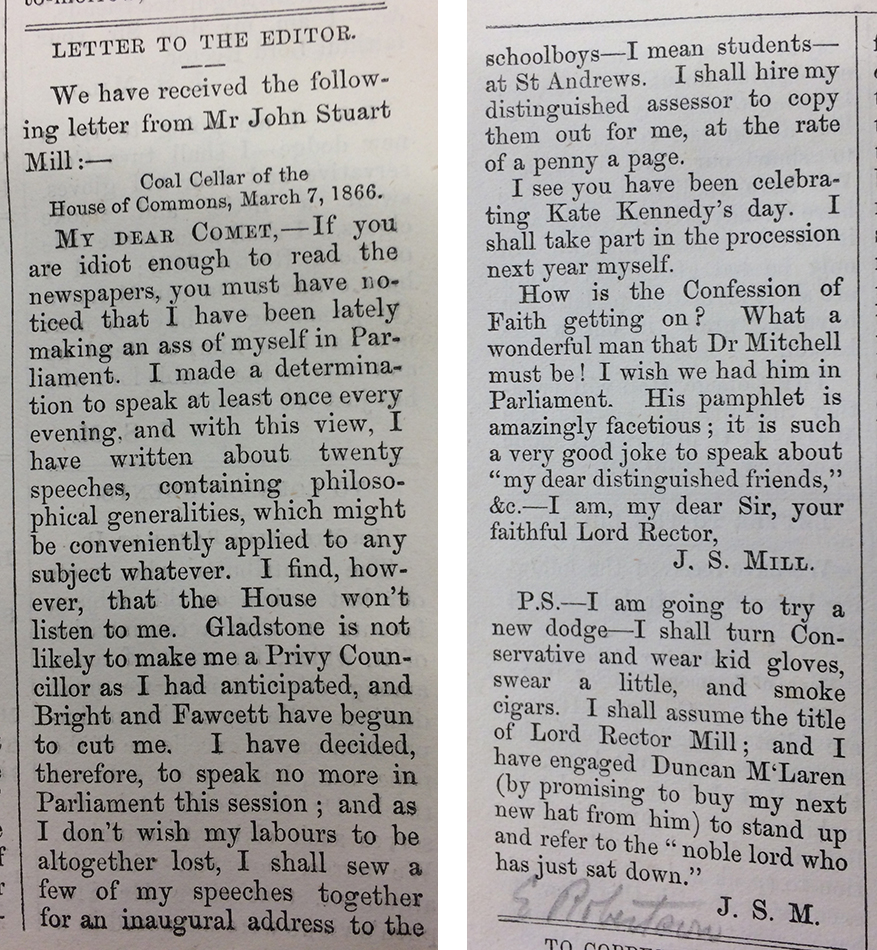

Invitations to stand as Rector come from the students. In November 1865 The Comet, a short-lived student magazine, recorded that various names were under consideration: ‘The University wants a Lord Rector, and it does not know where to get one. There is at present a sad dearth of eminent Scotchmen fitted for such an office and the task of obtaining one will be of surpassing difficulty. Amongst other names there are mentioned Mr Duncan McNeil, president of the Court of Session; Lord Justice Clerk Inglis; Edward Ellice, esq., MP for the St Andrews Burghs; Walter Thomas Milton, esq, Provost of St Andrews; and last, but by no means least, the Editor of The Comet.’ Walter Weir Tulloch, son of the Principal of St Mary’s College, who went on to become a Minister of the Church of Scotland in Greenock, Kelso and Glasgow and who wrote for The Comet, wrote to ask John Stuart Mill if he would stand. The invitation was initially met with a refusal, as this letter to WW Tulloch shows:

Avignon, Nov 20 1865

Dear Sir

I feel very much honoured by the desire of some of the Students to elect me to the office of Rector of the University of St Andrew’s; but from the inclosure in your letter, the duties and responsibilities of the office appear to be considerable, and such as I could not fulfil without neglecting other duties which in my case are of higher obligation. I must therefore, with sincere thanks to those who have done me the honour of thinking of me, respectfully request that I may not be put in nomination.

I am dear Sir,

Yours very sincerely, J.S. Mill

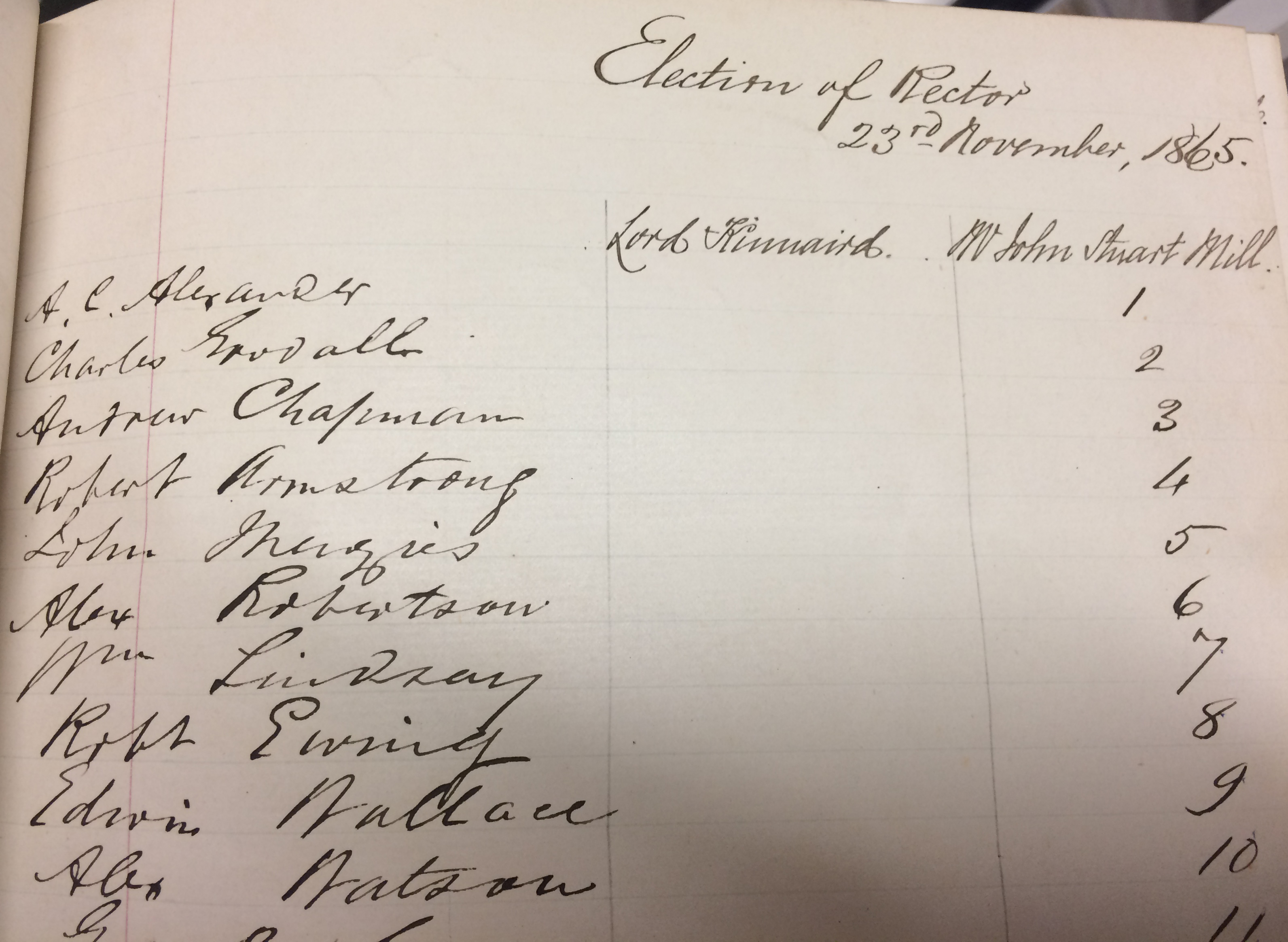

Despite this, in some way Mill’s concerns were allayed and he did allow his name to go forward in the election, which took place on 23 November 1865. He was opposed by Lord Kinnaird, 1st Baron Kinnaird of Rossie, Perthshire landowner and Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, a local agricultural improver, enlightened landowner, scientist and photographer. The result was decisive – 96 votes for Mill, 48 for Kinnaird with 26 abstentions.

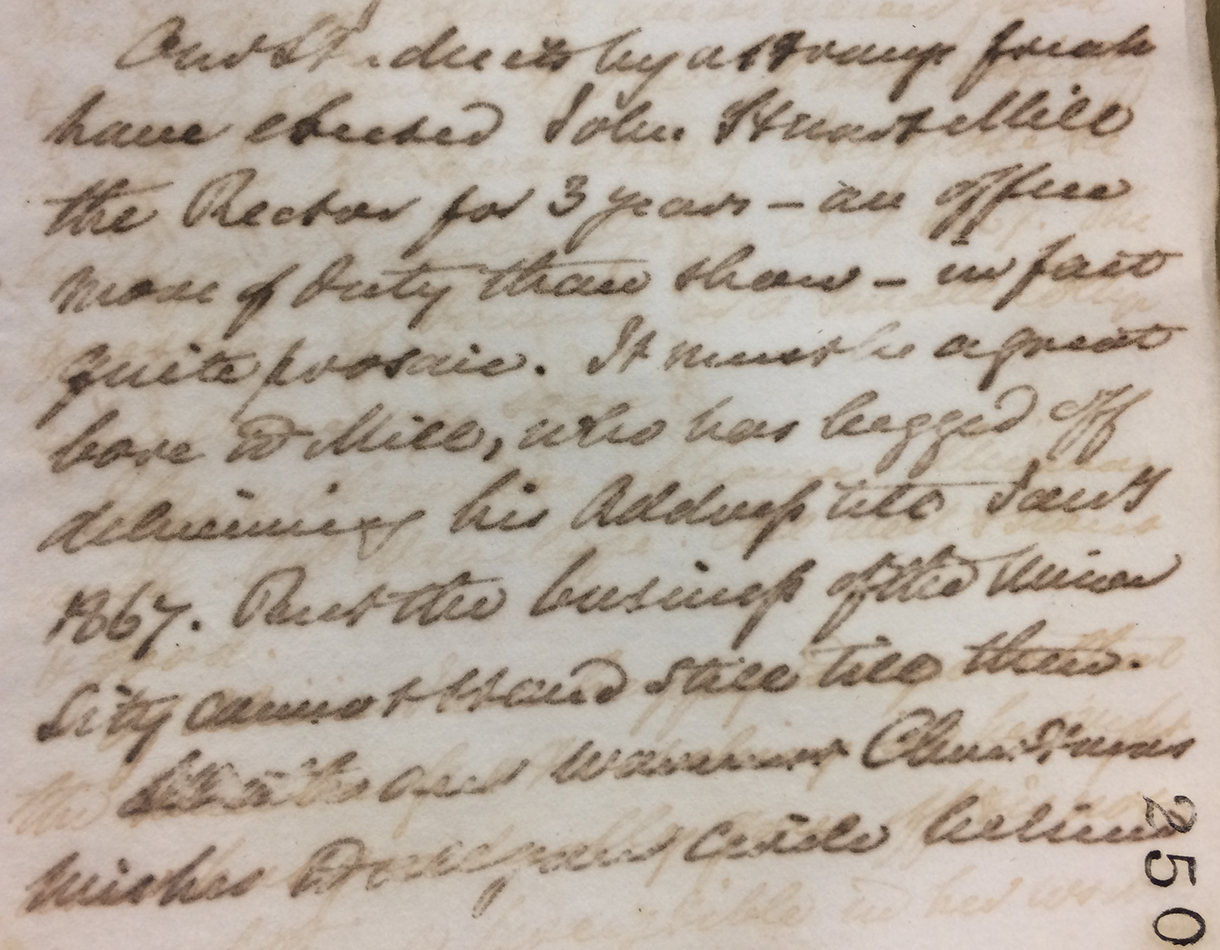

There seems to have been little contact with the University from the new Rector, then also a newly elected MP and active in the House of Commons. James David Forbes, Principal of the United College, had an interesting perspective on the election, noting that:

Our students by a strange freak

have elected John Stuart Mill

the Rector for 3 years – an office

more of duty than show – in fact

quite prosaic. It must be a great

bore to Mill, who has begged off

delivering his Address till Janry

1867. But the business of the Univer

sity cannot stand still till then.”

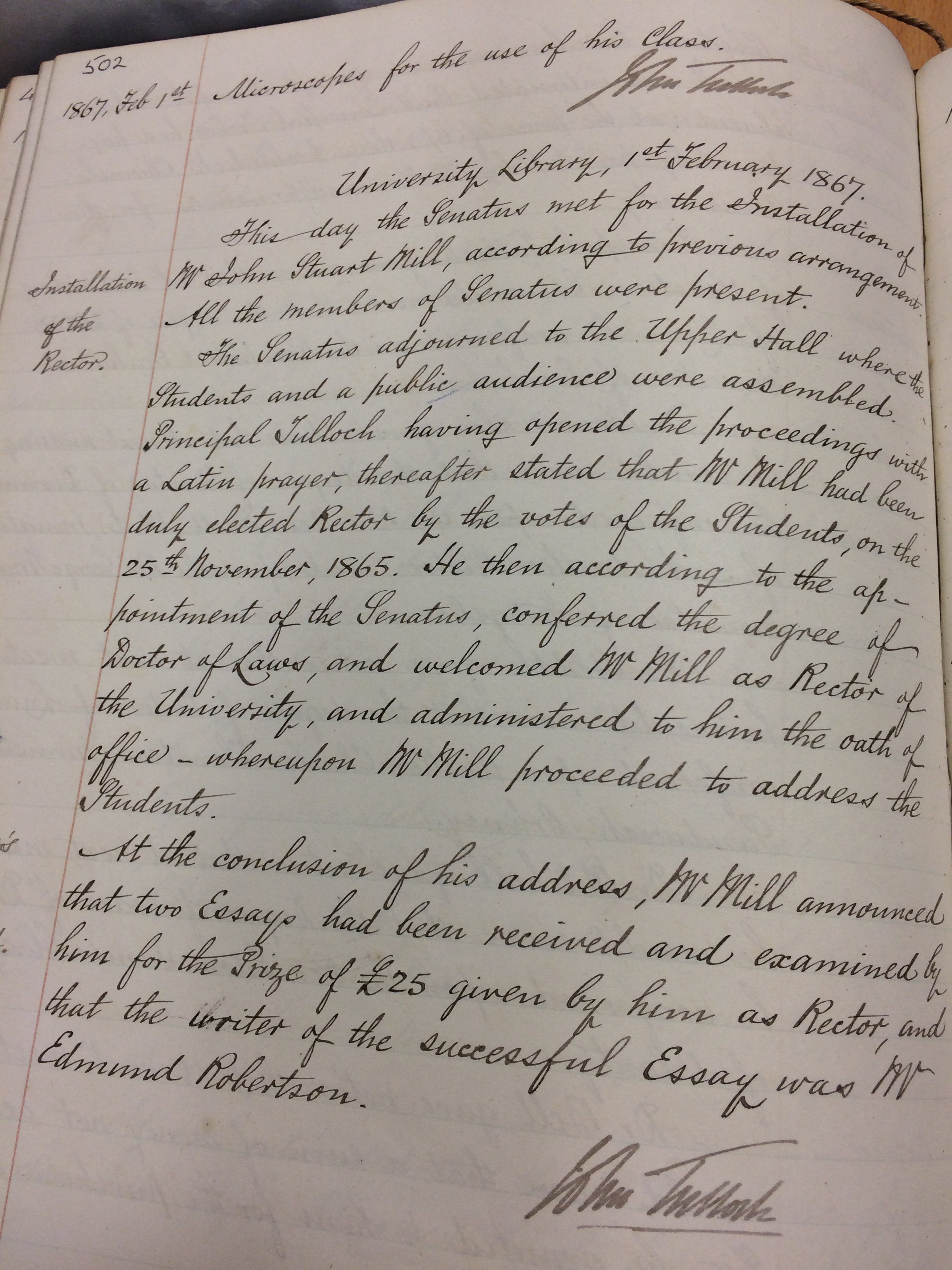

By the Spring of 1866 there was a satirical student request for a petition to senatus ‘By Mr J.S. Mill . – – “That the University Court be requested in future to hold its sittings during the session (parliamentary) in London, as near St Stephen’s as possible, and after the session, at Avignon.’ At this time Mill split his residence between London and the south of France. In December 1866 the Senatus heard that Mill was to be in St Andrews on 31 January 1867, and accordingly set up a committee to make arrangements for the installation on the following day, agreeing to confer the degree of Doctor of Laws on Mill on the occasion and that the dinner expenses should be paid for ‘out of the University Chest’.

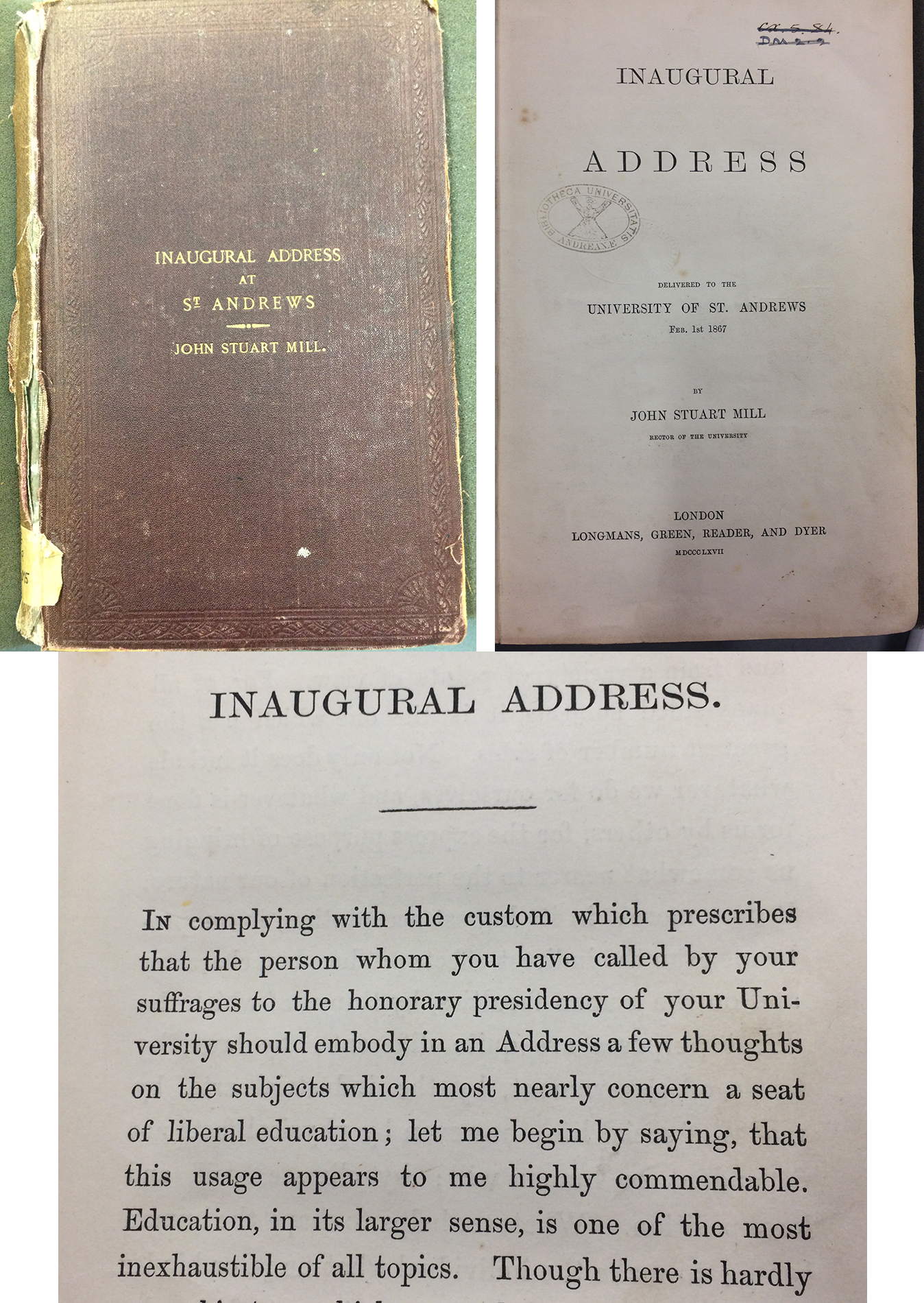

The presence of the controversial ‘democrat and atheist’ Rector, (as Principal John Shairp described him) guaranteed a full attendance by Senatus and a large student and public audience to hear his address in the Upper Hall of the University Library, now known as the King James Library. The Principal ‘opened the proceedings with a Latin prayer’ (as is still the case at graduation ceremonies which are also meetings of Senatus), without compromise in the face of the honoured guest’s agnosticism. The honorary degree was conferred, the welcome and oath of office administered and then the Rector ‘proceeded to address the students’. This address is 23,000 words long, the longest rectorial address ever delivered, and apparently lasted for three hours, even though Mill spoke quickly.

In his opening words, Mill set the pattern for the activity, or lack of it, of successive Rectors, until the election of the Marquis of Bute in 1892. He defined the role as ‘the honorary presidency of your University’. He was never a working rector, but rather an eminent man with whom the University students wished to be associated: ‘a man whose literary fame would shed lustre and dignity on any society with which he was connected’ (The Comet, issue 1, November 1865 StA LF1119.A2C71). However, in a statement ahead of its time, that same article in The Comet continues with the wish of the students to see the rector acting as representative of those who elected him. As a supporter of the rights of women, JS Mill would have been delighted to see a female Lord Rector succeeding him, but might have been less sanguine about her exercise of the primary representative role of the active University Rector today.

Rachel Hart

Keeper of Manuscripts and Muniments

[…] laws.[4] Harriet Taylor’s husband was the MP and philosopher John Stuart Mill who was also Rector of the University of St Andrews between 1865 and […]

JSM was almost always right. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/10/06/right-again

Dear Ms Hart, can you please advice me whether or not this speech consists of the followings: “Let not any one pacify his conscience by the delusion that he can do no harm if he takes no part, and forms no opinion. Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing. He is not a good man who, without a protest, allows wrong to be committed in his name, and with the means which he helps to supply, because he will not trouble himself to use his mind on the subject.” I did skim the booklet, but could not find it. My boss wants me to make sure the quote we want to use is definetly of Mr Mill and not Edmund Burke (see here: https://www.openculture.com/2016/03/edmund-burkeon-in-action.html) Thank you very much. Lilla

Dear Ms. Hart, could you tell me if, besides the printed copy of Mill's inaugural speech, your special collection also holds an electronically scanned copy of Mill's manuscript or his handwritten preparatory notes, if any such documentation exists at all?