Banned Books at the University of St Andrews

This week, 24-30th September, celebrates Banned Books week. Banned Books Week is an annual celebration, launched in 1982 by the American Library Association, aimed at promoting the freedom to read. Books might have been banned for a variety of reasons, including censorship, fear of the corruption of young minds, diversion from studies, prevention of theft, and the protection of the University’s investment in expensive and rare editions. Here at St Andrews we thought we would share with you some extracts from our Minutes of Senatus, 1820-1821, when students of Divinity petitioned to have access to ‘banned’ books.

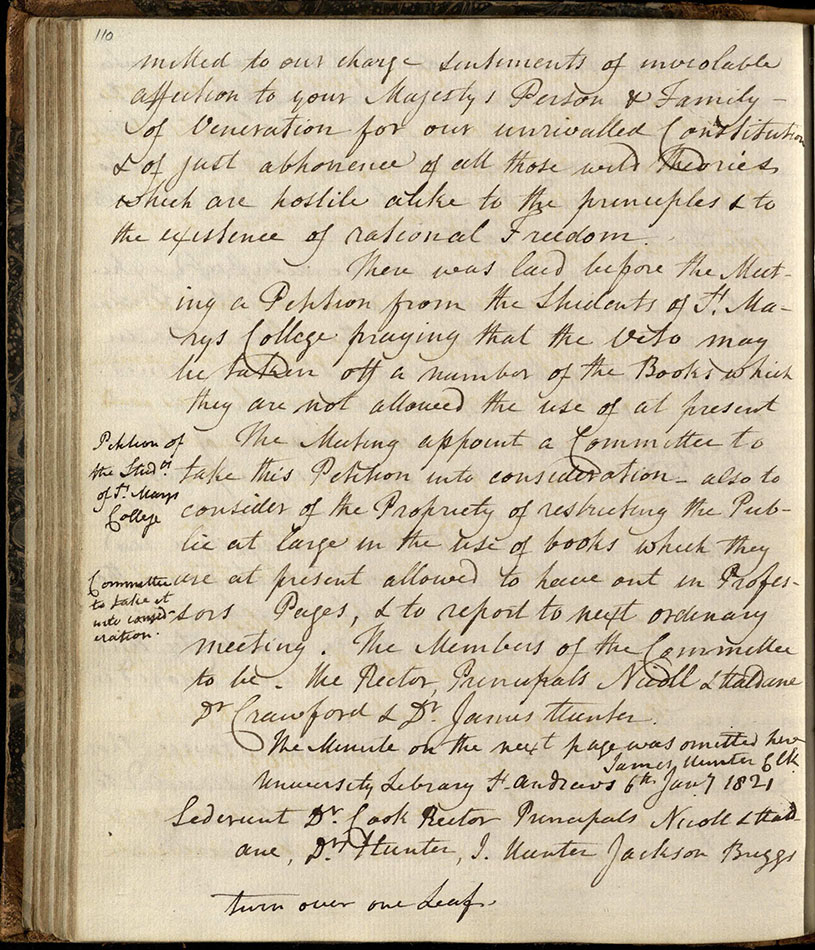

There was laid before the Meeting a Petition from the Students of St. Mary’s College praying that the Veto may be taken off a number of the Books which they are not allowed the use of at present. The Meeting appoint a Committee to take this Petition into consideration – also to consider of the Propriety of restricting the Public at large in the use of books which they are at present allowed to have out on Professors’ pages, and to report to next ordinary meeting.

The Committee appointed on the 14th December gave in the following Report.

That the veto & all the Regulations respecting the Library should continue as formerly, with the exception of the following proposed alterations-

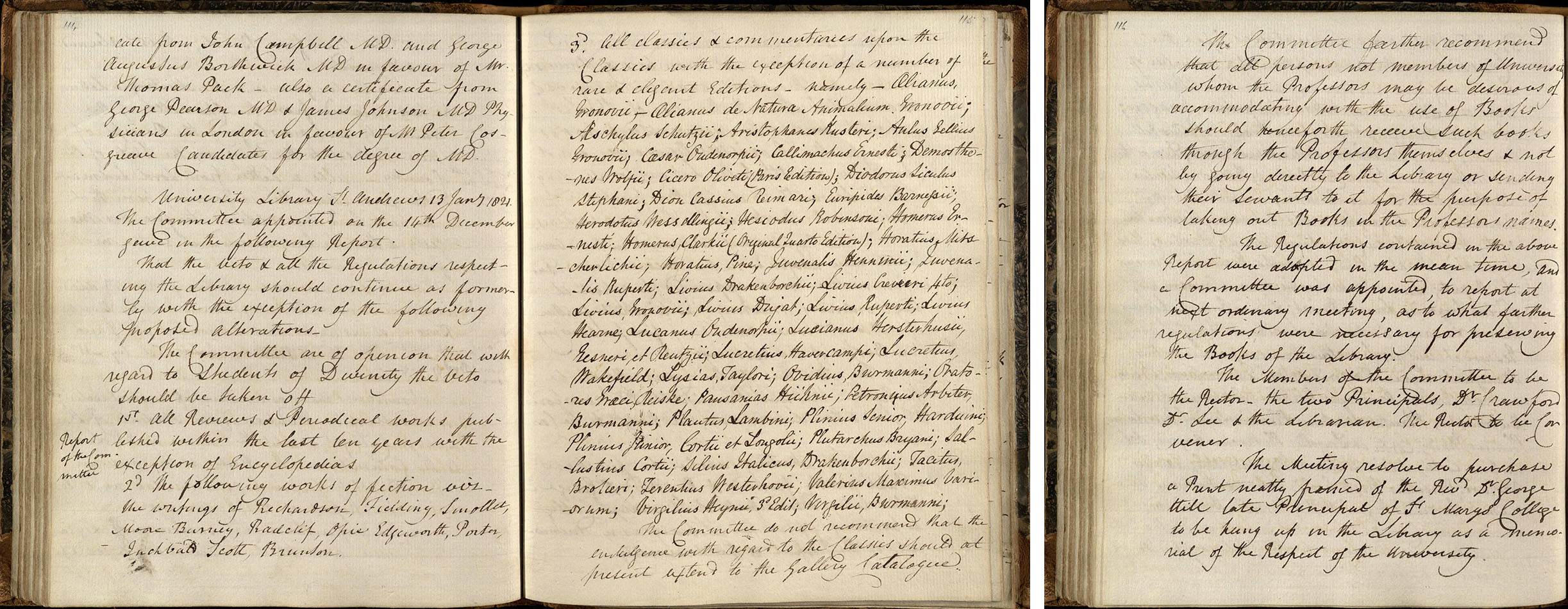

The Committee are of opinion that with regard to Students of Divinity the Veto should be taken off

1st. All Reviews and Periodical works published within the last ten years, with the exception of Encyclopedias

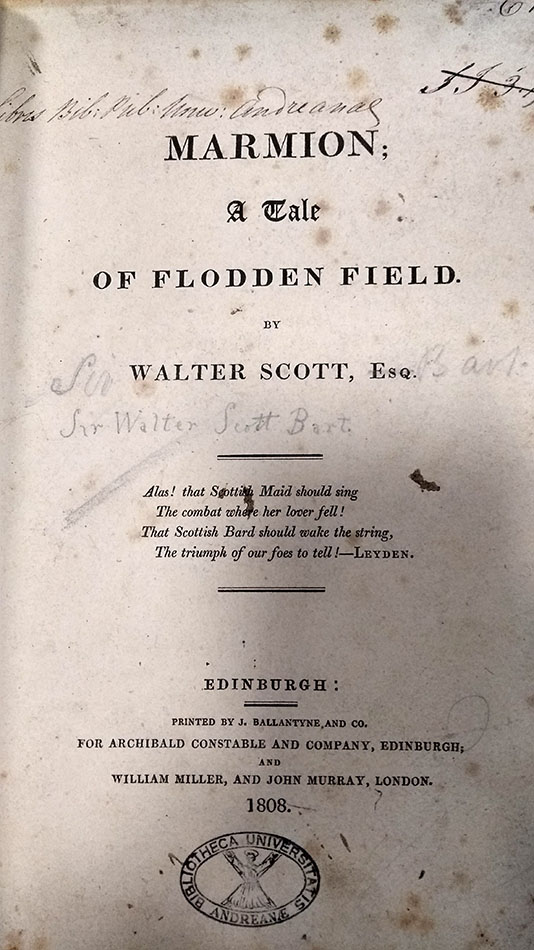

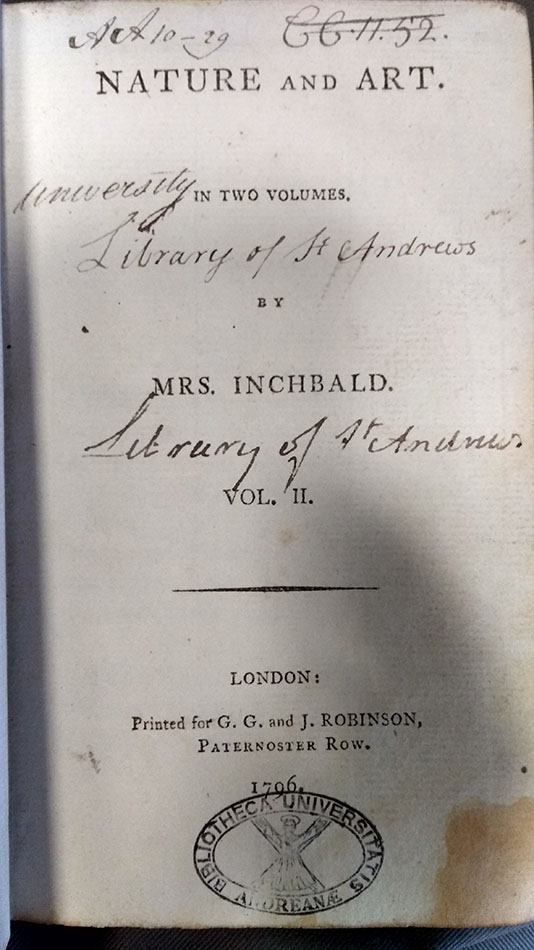

2d. The following works of fiction, viz- The writings of Richardson, Fielding, Smollet, Moore, Burney, Radcliffe, Opie, Edgeworth, Porter, Inchbald, Scott, Brunton.

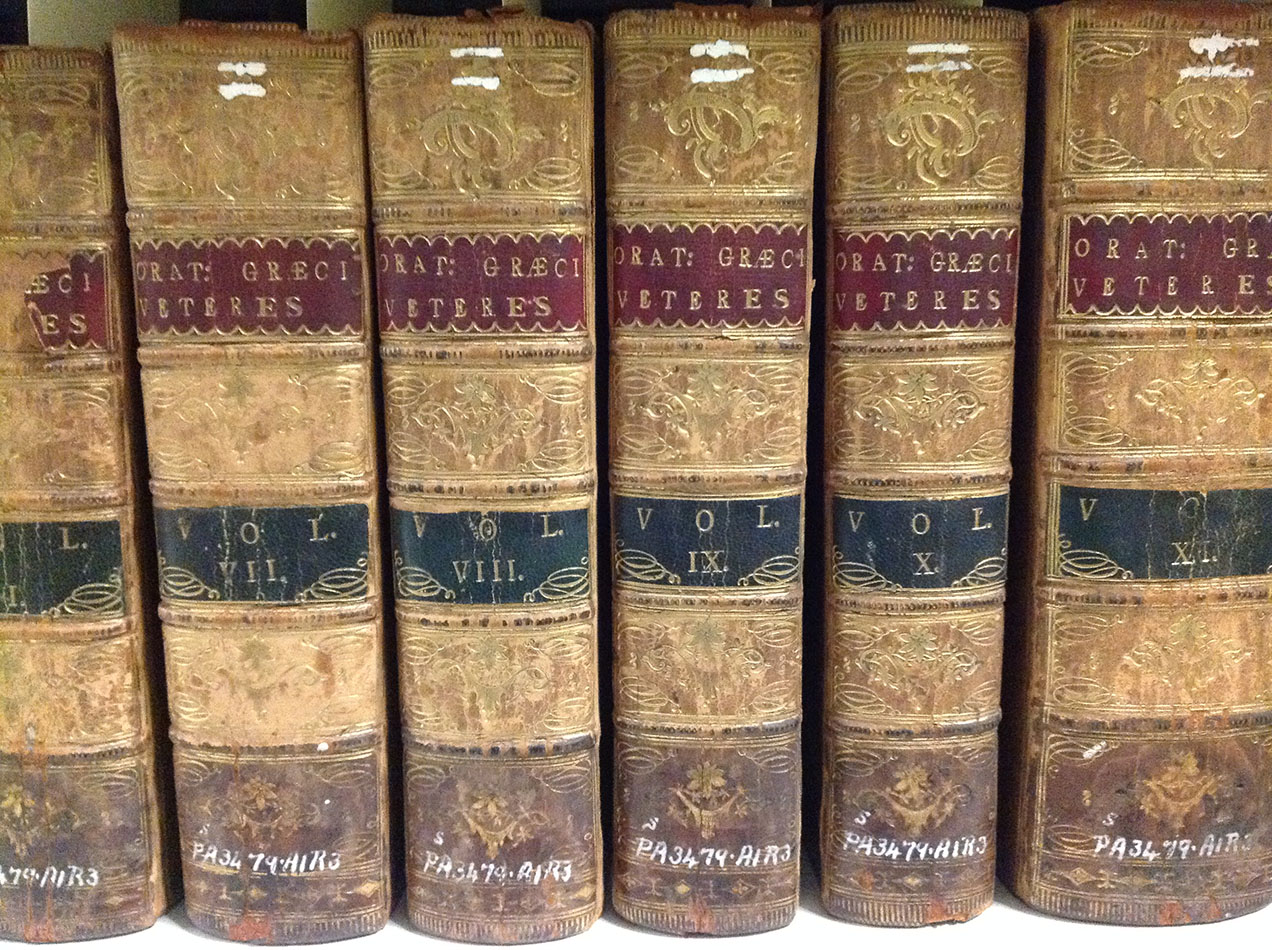

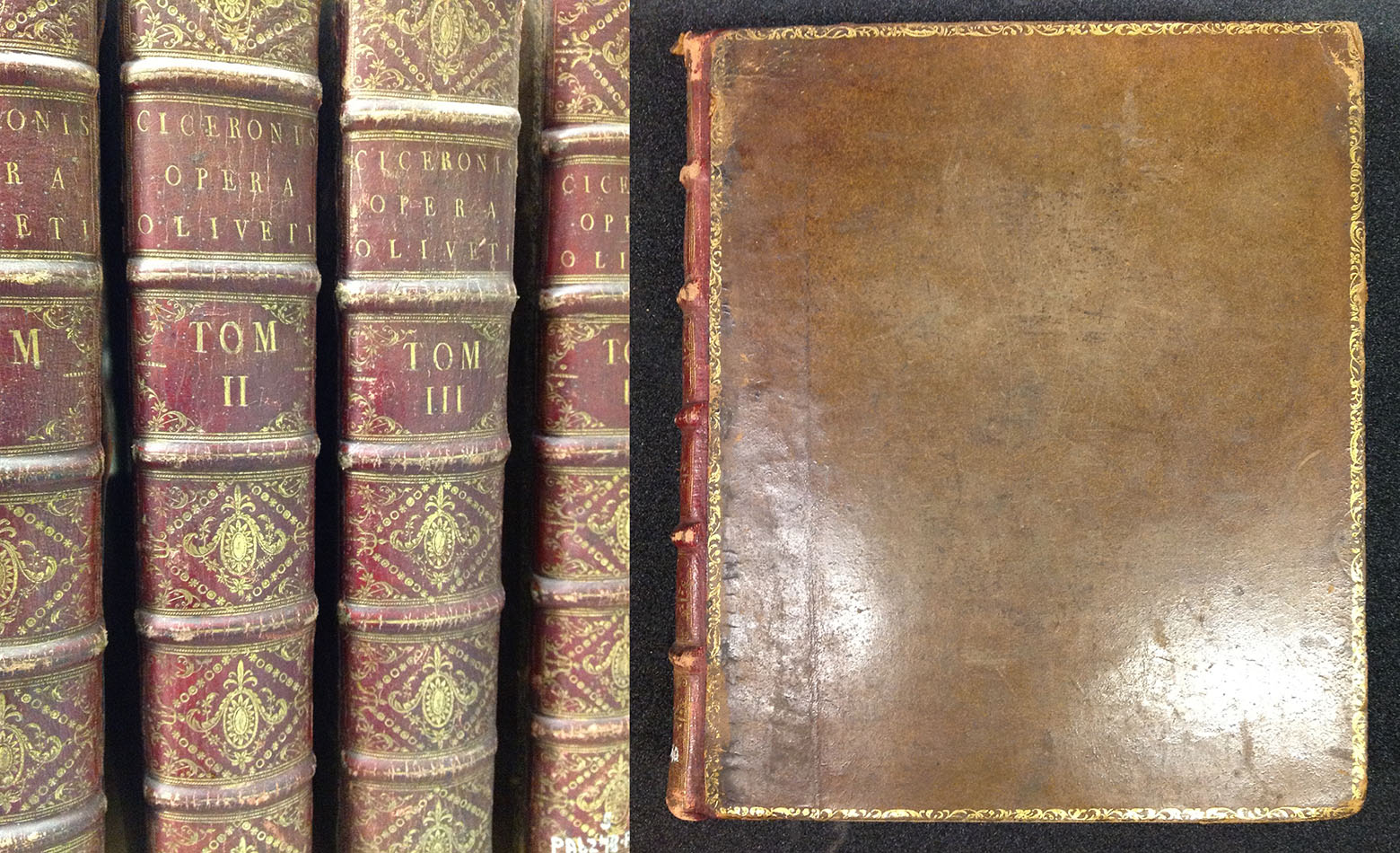

3d. All classics and commentaries upon the Classics, with the exception of a number of rare & elegant Editions – namely – Aelianus Gronovii – Aelianus de Natura Animalium Gronovii; Aeschylus Schutzii; Aristophanes Kusteri; Aulus Gellius Gronovii; Caesar Oudendorpii; Callimachus Ernesti; Demosthenes Wolfii; Cicero Oliveti (Paris edition); Diodorus Siculus Stephani; Dion Cassius Reimari; Euripides Barnessii; Herodotus Wesselingii; Hesiodus Robinsoni; Homerus Ernesti; Homerus Clarkii (Original Quarto Edition); Horatius Mitscherlichii; Horatius Pine; Juvenalis Henninii; Juvenalis Ruperti; Livius Drakenborchii; Livius Crevieri, 4to; Livius Gronovii; Livius Dujat; Livius Ruperti; Livius Hearne; Lucanus Oudendorpii; Lucianus Hersterhusii [sic], Gesneri et Reutzii [sic]; Lucretius Havercampi, Lucretius Wakefield; Lysias Taylori; Ovidius Burmanni; Oratores Graeci, Reiski; Pausanias Kühnii; Petronius Arbiter Burmanni; Plautus Lambini; Plinius Senior Harduini; Plinius Junior Cortii et Longolii; Plutarchus Bryani; Sallustius Cortii; Silius Italicus, Drakenborchii; Tacitus Brotieri; Terentius Westerhovii; Valerius Maximus Variorum; Virgilius Heynii, 3d Edit; Virgilii Burmanni;

The committee do not recommend that the indulgence with regard to the Classics should at present extend to the Gallery Catalogue.

The committee farther recommend that all persons not members of the University whom the Professors may be desirous of accommodating with the use of Books should henceforth receive such books through the Professors themselves & not by going directly to the Library or sending their Servants to it for the purpose of taking out Books in the Professors’ names.

The regulations contained in the above Report were adopted in the mean time, and a Committee was appointed, to report at next ordinary meeting, as to what farther regulations were necessary for preserving the Books of the Library.

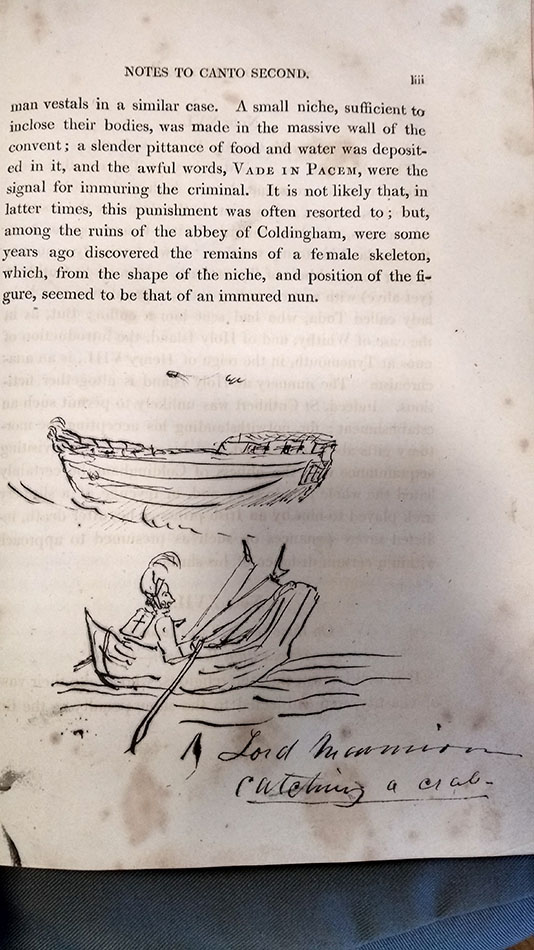

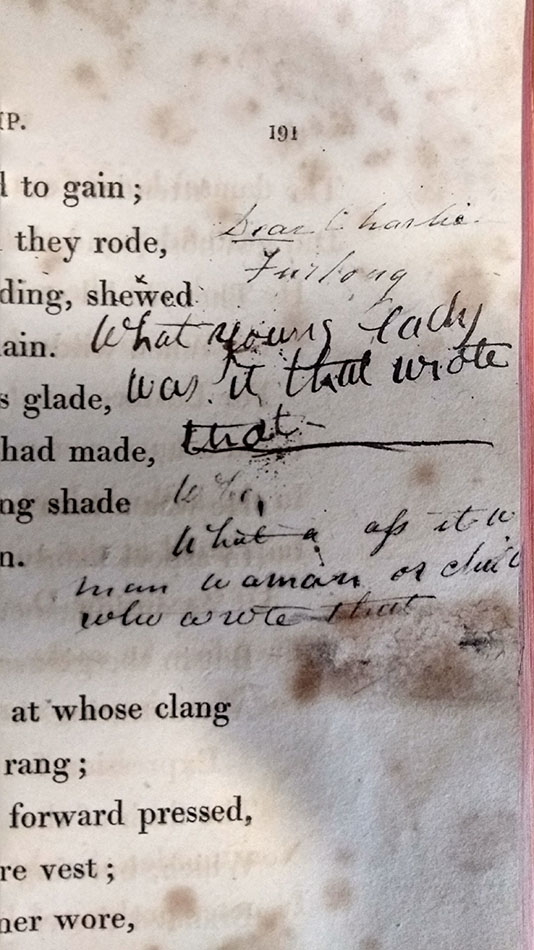

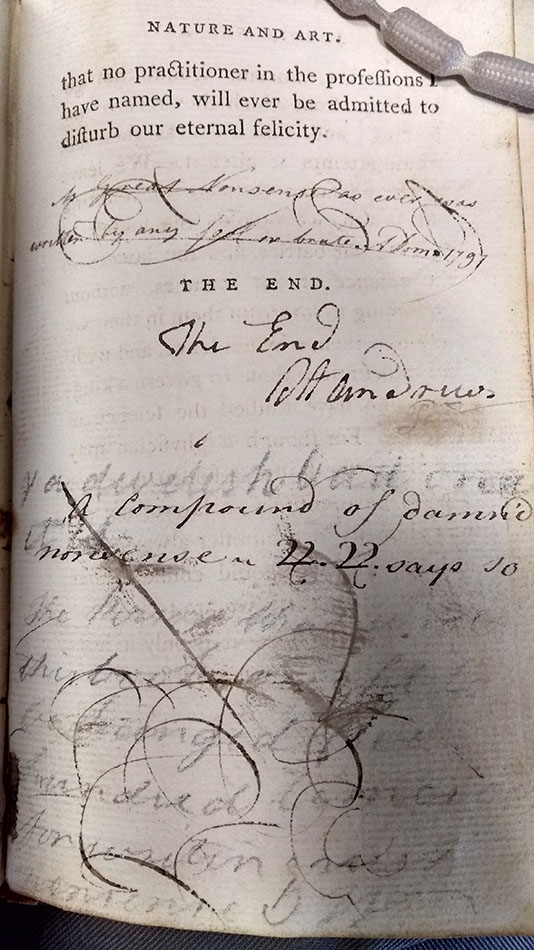

The committee lifted the ban on ‘The writings of Richardson, Fielding, Smollet, Moore, Burney, Radcliffe, Opie, Edgeworth, Porter, Inchbald, Scott, Brunton,’ and some examples of these authors’ works, which have been in the Library since their publication, show evidence of keen reading by the student body. Was the University Senate justified in the original ban?

Whilst the ban was lifted on some books, others (those ‘rare & elegant Editions’ of the Classics) were still forbidden to students or visitors, ‘for preserving the books of the lIbrary’.

The "veto" is clearly the same as putting certain popular titles and authors "on reserve" in order to serve the students more fairly, just as we do today. Note also that the encyclopedia remains on veto, meaning it is a reference book for use in the library as opposed to circulating. These are not "banned" books, they are simply "on reserve" or "for reference only."

Hi David, thanks for your comment. The meaning of the term "veto" is somewhat ambiguous in this context. Yes, the students could simply have been prohibited from borrowing rather than reading. However, the term "not allowed the use of" suggests there was an attempt to control students’ use of books and their access to certain types of material. It is in this sense that we have described the books as "banned".

[…] blog, Echoes from the Vault, I was reminded of these luminaries. The latest blogpost, ‘Banned Books at the University of St Andrews‘, shares early 19th century Senate discussions as to which books should remain banned to […]