2017 Visiting Scholarship: Newburgh Burgh Court Book, 1457-79

In the second of our reports, Dr William Hepburn, University of Aberdeen, shares with us some of his findings during his Visiting Scholarship in the summer of 2017.

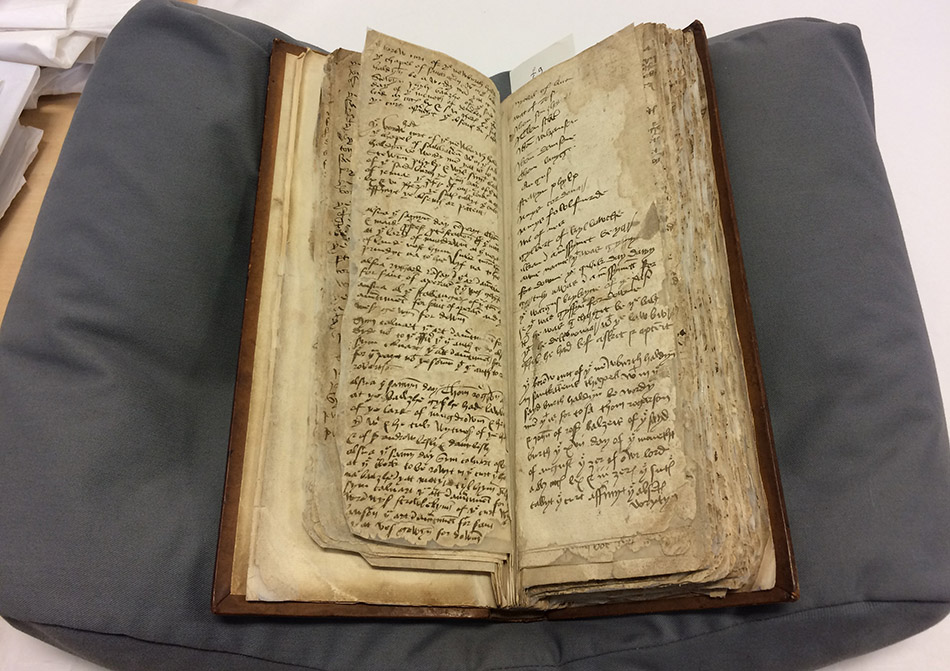

In August of this year I had the opportunity to spend four weeks as a visiting scholar at the University of St Andrews Library Special Collections. My focus was a fifteenth-century burgh court book from Newburgh in Fife, covering the years 1457-80 (B54/7/1) transferred to St Andrews by the Keeper Records of Scotland. It is one of the few examples of such books to survive from Scotland before the sixteenth century. Burghs were created as centres of trade and commerce. Creating a burgh meant conferring of a set of legal privileges on a select group of people in order to generate revenues for the party creating the burgh. The burgh community consisted of those who enjoyed these privileges. This corporate body, and officers chosen from amongst it, governed the privileges of the town. They created local legislation, enforced laws through burgh courts and administered the common property of the burgh. Books such as the Newburgh Burgh Court Book – often referred to by contemporaries as ‘common books’ – were used to record the deliberations and actions of burgh governments and the communities they represented. In this post I will highlight some of the treasures of the Newburgh Burgh Court Book, especially voting for burgh officials, a violent feud and a joke about a drunk priest.

Votes

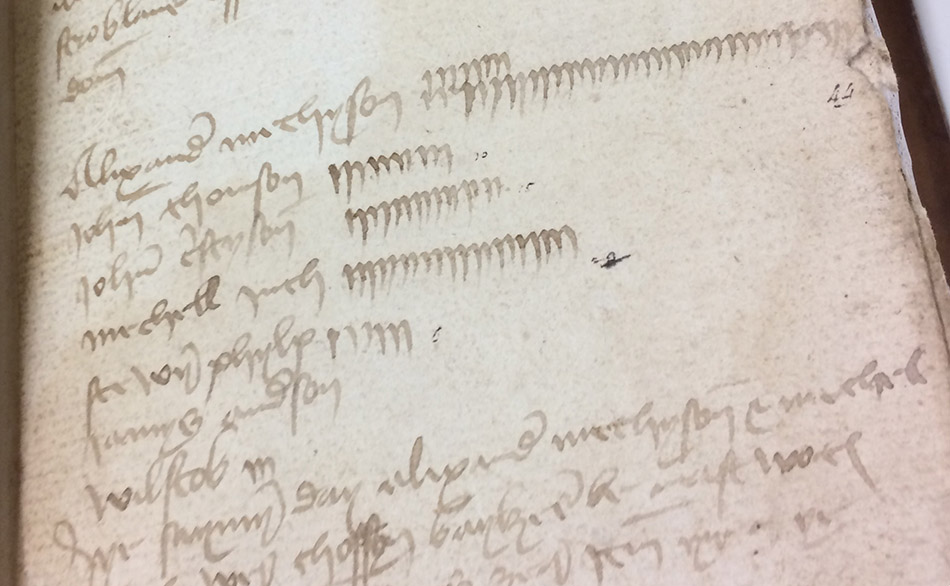

There is very little surviving evidence to show exactly how burgh officials were chosen in medieval Scotland. William Croft Dickinson, in a 1957 Scottish History Society volume, was only able tentatively to infer that baillies were elected from among the burgesses at the Michaelmas head court, as stipulated in the Leges Quatuor Burgorum. Aberdeen’s burgh registers frequently state that individuals were elected to the office of baillie but say very little about the process of the election. The Newburgh Burgh Court Book reveals vote counts from such elections. In several places in the book a list of names appears with a number of strokes penned after each name. One, apparently from the Michaelmas head court, explains what these lists record. After a list in which Alexander Mathison and Michael Inch have the most strokes after their name it states that the pair ‘wer chossyn bayleis be mast wotis’, showing that the lists and strokes record the candidates for the office and the votes they received. We can only imagine that James Anderson must have been disappointed if, as the depicted record tells us, he did indeed get no votes at all.

A violent feud

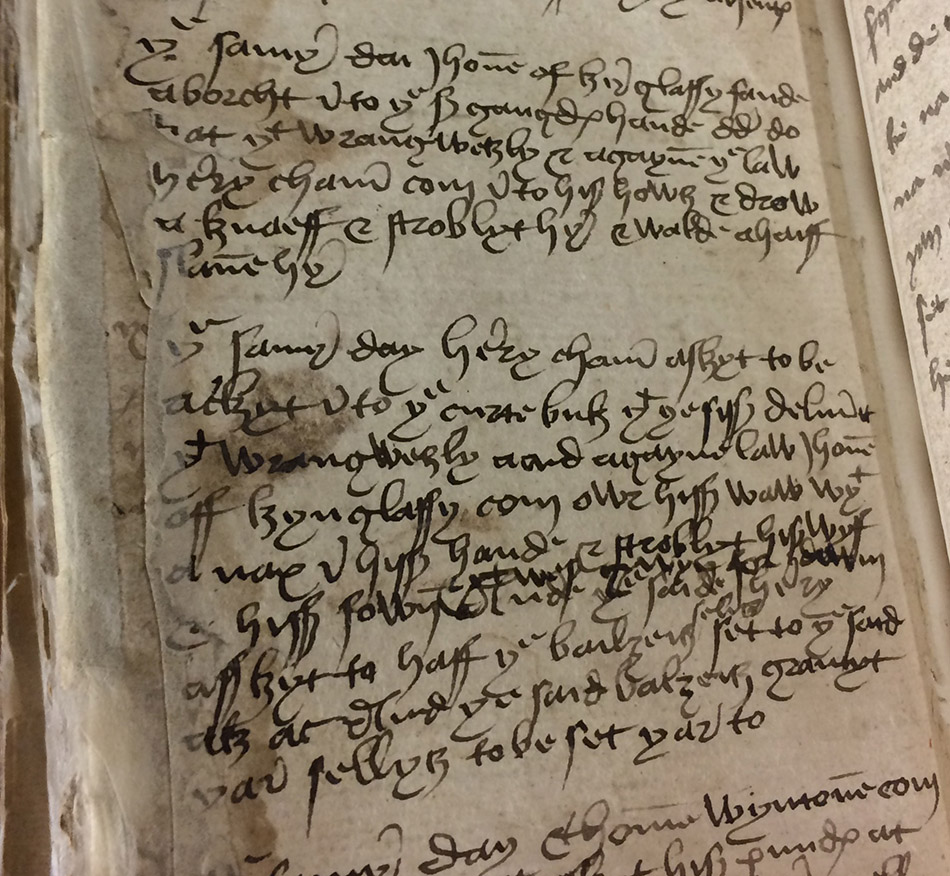

Scottish burgh records of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are full of records of punishments issued by burgh authorities for violence and other disturbances. However, in most records from prior to the sixteenth century these incidents are only described in vague terms. Newburgh’s fifteenth-century records provide an unusually detailed account of a violent feud between two members of the burgh community. Though the cause of their feud is not made clear, some detailed claims of wrongs were made by both parties. In February 1480 John of Kynglassy came to Newburgh Burgh Court to claim that Henry Chamer, ‘wrangwesly and agayne the law’, came into his house and drew a knife and attempted to kill him. On the same day Henry Chamer made the counter-claim that, also ‘wrangwesly aand agayne law’, John of Kynglassy had come over his wall with an axe in his hand and attacked or threatened his wife and son. That these claims were recorded in such unusual detail suggests this was a particularly contentious or complex case.

A drunken priest

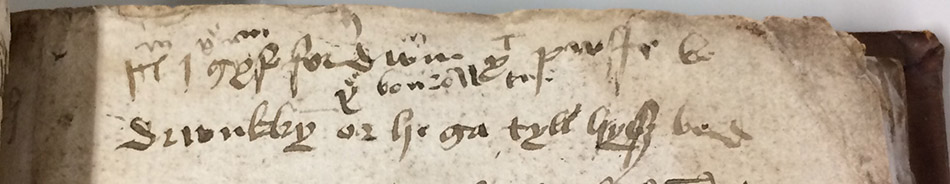

Burgh Records represent some of the richest sources for the early history of Scots as a written language. The Newburgh Burgh Court Book is particularly valuable in this regard as it is written almost entirely in Scots, as opposed to the Latin often used in similar books from other burghs. Scots in this period is better known as a literary language through the work of poets such as William Dunbar. Scholars have shown that these two spheres of Scots writing are not as far apart as they may seem. The men, often notaries, who wrote burgh registers were involved in the production and collecting of literary texts, as Sebastiaan Verweij has [1].Writers like Robert Henryson brought the styles and language they had learned from legal work into their literary output [2]. A scribe writing in the Newburgh Burgh Court book did something like this when he adopted one of the formulae used in the book to make a joke about a drunk priest. Records of legal proceedings in the book often include the phrase ‘… and that was given for doom’ after the details of a legal judgement are outlined. In the margins of one page a Newburgh scribe wrote:

Item I gyf for dwm that preste be

drwnkkyn or he ga tyll hyss bed’.

‘And I give for doom that priest is drunk before he goes to his bed.’

Who exactly the scribe might have been making fun of here we can’t know, but by subverting the formulae of his day job to humorous effect he showed one means by which writers could blur the lines between pragmatic and literary modes of writing.

These and other insights gained from my time spent working at St Andrews Library Special Collections are offering new perspectives on my broader research into late medieval burgh records as part of the Law in the Aberdeen Council Registers project (https://aberdeenregisters.org/). I would not have gained such insights but for the generosity of the visiting scholarship and the warm welcome and kind assistance given by the Special Collections staff when I was there.

William Hepburn

University of Aberdeen

[1] Sebastiaan Verweij, The Literary Culture of Early Modern Scotland: Manuscript Production and Transmission, 1560–1625 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 126-34.

[2] Robert L. Kindrick, ‘Robert Henryson and the Ars Dictaminis’ in McClure, Derrick and Spiller, Michael (eds.), Bryght Lanternis: Essays on the Language and Literature of Medieval and Renaissance Scotland (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1989), pp. 150-61.

[…] for the entries recently uncovered in Newburgh’s registers by LACR’s William Hepburn (see the post on his visiting scholarship at St Andrews University Library Special Collections). In Dubrovnik […]