Rescued from the Ruins: The Surviving Manuscripts of St Andrews Cathedral

Today, the east end of St Andrews is dominated by the ruins of its former Cathedral. Once the largest building in Scotland, St Andrews Cathedral held the shrine of the nation’s patron saint, was the base for the kingdom’s senior bishopric (from the 1470s onwards the country’s first archbishopric), and was served by Scotland’s most important monastic community. Indeed, in the early fifteenth century, the chronicler Walter Bower described St Andrews Cathedral as ‘the lady and mistress of the whole kingdom’, and emphasised that its clerics took precedence over all other Scottish churchmen. Yet, for more than 450 years this remarkable building has been open to the elements.

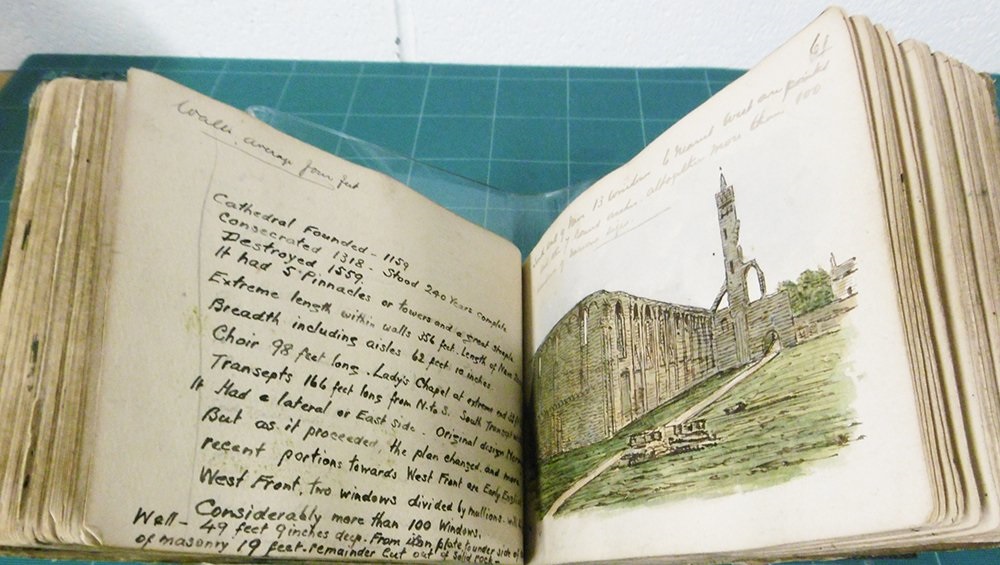

In the summer of 1559 St Andrews Cathedral, traditionally the hub of Catholicism in Scotland, was attacked by committed Protestants. According to Sir James Croft, in a contemporary report sent to the English government, the Reformers ‘put down the [Cathedral] priory of St Andrews in this sort: altering the habit, burning of images and mass books and breaking of altars’. Not long afterwards, the Cathedral’s lead roof was stripped off, and local residents began to remove masonry, causing the glories of the medieval church to descend rapidly into ruins. As early as the 1590s, the Scottish Parliament noted regretfully that St Andrews Cathedral

‘is for the most part already decayed, and daily decays and becomes ruinous in such sort that the same, by process of time, will utterly decay’.

However, this summer marks a happier moment in the Cathedral’s story – 5 July marks 700 years since the main Cathedral church was consecrated by Bishop William Lamberton in the presence of King Robert the Bruce. The late medieval chronicler Andrew Wyntoun (lived c.1350 to 1422) later celebrated the occasion in verse, recording that:

A thousande thre hundir yhere and auchteyne

Fra Crist was borne of the Maydyn cleyne,

Off the monethe of Iuly

The fift day, ful solempnely

The bischope Wilyame of Lambertone

Mad the dedicacion

Off the new kirk cathedrall

Off Sanctandrois conuentuall.

The king Robert the Bruss honorably

Wes thare in persoune bodely;

And vii. bischopis thare wes sene,

And abbotis als were thare fiftene…

On such an anniversary, rather than regretting what has been lost, it is perhaps worthwhile considering what has survived from the Cathedral – including a varied (and now geographically scattered) selection of manuscripts from the Cathedral Priory.

St Andrews Cathedral had a tradition of book collection and creation that stretched back long before 1318. There had been a religious site at the east end of St Andrews since at least the eighth century A.D. Although none of the early religious community’s books survive, there is reason to believe they did own them. Walter Bower claimed that he had seen at St Andrews ‘the silver cover of a gospel book’ engraved with the words:

‘Fothad, who is the leading bishop among the Scots,

Made this cover for an ancestral gospel-book.’

Details of Fothad’s life and career are sketchy, but he is thought to have died around 963. Sadly these early medieval books did not survive the ravages of time. Instead, the surviving manuscripts from St Andrews Cathedral date from the twelfth century or later.

The twelfth century was a time of change in St Andrews. The Culdees or ‘Celi De’, holy men from a Celtic tradition who had formerly guarded the shrine of St Andrew, were driven out from the Cathedral and replaced by ‘regular’ Augustinian canons, influenced by English and Continental customs. With the backing of successive bishops, the Augustinian canons embarked on a series of major building projects, including, in the 1160s, starting work on the new Cathedral church which was eventually completed in 1318. Like other great monastic communities, the canons at St Andrews Cathedral created and preserved a variety of texts including liturgical and musical works, theological writings, histories, and a vast body of administrative documentation – a number of which exist to this day.

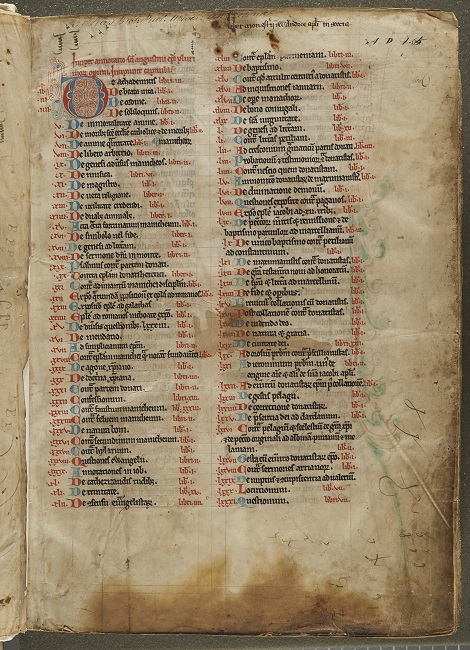

Perhaps the most remarkable extant manuscript from the Cathedral Priory is a twelfth-century collection of works by St Augustine of Hippo (now in the University of St Andrews Library’s Special Collections as msBR65.A9). The vast volume, bound between oak boards, is thought to date from around 1190, and was probably copied by hand in St Andrews. The book seems to have been preserved at the time of the Reformation by John Winram, the sub-prior at the Cathedral, who, despite participating in the prosecution of heretics as late as 1558, subsequently became a leading figure in the Protestant Church of Scotland.

Other extraordinary survivals include a collection of manuscripts which were removed from St Andrews Cathedral by a German named Marcus Wagner in 1553, and are now kept in the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel. Marcus Wagner originally came from Friemar, and was a keen and rather unscrupulous acquirer of old manuscripts, on behalf of the eminent historian and theologian Flacius Illyricus. In the spring of 1553 Wagner came to St Andrews where he was invited for a meal at the Cathedral Priory by Lord James Stewart, the illegitimate son of King James V who was commendator of the priory. While Lord James was preoccupied with entertaining another aristocratic guest, and a woman described as ‘Lady Venus’, Wagner slipped away to visit the Cathedral library to identify books of potential interest to Flacius Illyricus. Wagner found several volumes, which he subsequently, with assistance of Lord James, removed to Germany – after having claimed to at least one suspicious member of the St Andrews community that they were nothing more than out-dated academic works on science and philosophy which were commonly to be found around universities.

In reality the manuscripts Wagner removed from St Andrews Cathedral were more varied. Chief among them was a unique fourteenth-century music book created for St Andrews Cathedral, which provides extraordinary evidence of the international influences on medieval Scottish music (this can be viewed online at: http://diglib.hab.de/?db=mss&list=ms&id=628-helmst&lang=en). Other manuscripts included a fifteenth-century manuscript of John of Fordun and Walter Bower’s famous Scotichronicon, which traced Scotland’s story from mythical origins to the time of the Stewart kings, and a volume which (among other works) had an account of the legend of the relics of St Andrew and their arrival in Scotland. Wagner also removed the letter book of the early fifteenth-century prior of St Andrews Cathedral, James Haldenstone, which provides an invaluable insight into the administrative preooccupations of the late medieval priory, and was published in 1930 by James Houston Baxter, under the title Copiale Prioratus Sanctiandree (BR788.S1H2).

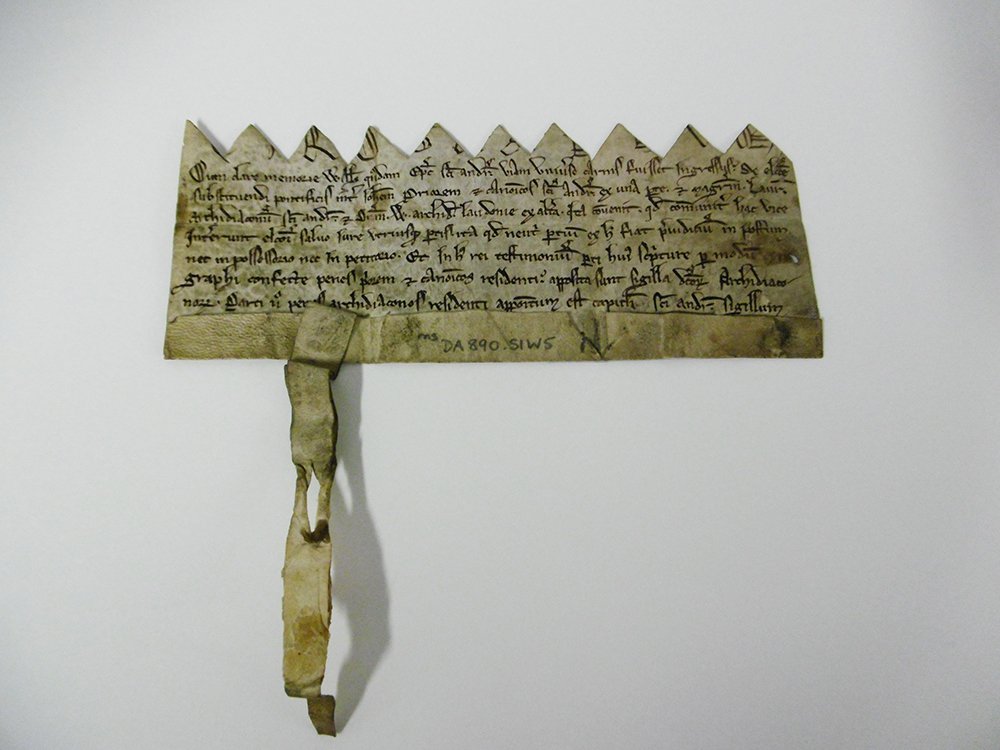

In St Andrews itself, the University Library’s Special Collections Division are fortunate in holding a large number of individual charters and pittance writs associated with the Cathedral – many of them preserved in the records of St Leonard’s College, which was founded by churchmen from St Andrews Cathedral, and which after the Reformation acquired a considerable portion of the Cathedral Priory’s estates. A large number of these documents were catalogued in detail by Special Collections near the start of this century, revealing the extraordinary content they contain on both the Cathedral and burgh of St Andrews. Despite seeming (to some eyes) to be dry legal documents, they are a unique insight onto the activities of the Cathedral, and the place it held in the local community, recording in many cases names, occupations, and residences of otherwise long-forgotten St Andreans. The potential of these documents has only begun to be unlocked thanks to cataloguing and recent work by scholars from the University of St Andrews. The ravages of time, and the tumults of St Andrews’s past mean much has been lost from St Andrews Cathedral. But, on the 700th anniversary of the consecration of the great Cathedral church, it is perhaps worthwhile remembering that the materials exist for much more research into this unique institution still to be done!

Dr Bess Rhodes

Smart History and School of History

Of course, the Cathedral Priory had been a centre of quasi-Protestantism in the years up to 1559. Perhaps the canons themselves supervised the destruction of the altars and mass-books.

Valuable information regarding an important time. Thank you for the insight to your research. So sorry to have missed you in March. Even though I could not connect with you personally, and most of the museums were closed, experiencing the physical locality strengthened my understanding immeasurably. I have been enlightened by your work in digital reconstruction of this important site.