Frankenstein in St Andrews

2018 marks the 200th Anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’. In honour of this anniversary, Dr Katie Garner of the School of English takes a look at the Library’s 1818 first edition of the novel and the contemporary publications listed in the publisher’s original advertisements.

The Library’s 1818 first edition copy of ‘Frankenstein’ is currently on display at Ingolstadt City Museum, as part of an exhibition in celebration of the 200th Anniversary.

The third and final volume of Frankenstein opens with Victor Frankenstein’s resolve to quit his family and fiancé in Geneva and embark on a two-year tour to England, where he will fulfil his promise of making the creature a female companion. (The creature’s side of the bargain is that he and his new mate will then emigrate to South America.) Travelling with his childhood friend, Henry Clerval, once the pair have arrived in England and spent ‘a considerable period’ in Oxford, it becomes clear that Scotland, not England, is Frankenstein’s desired destination and where he intends to once again begin the ‘filthy process’ of creating life from the remains of the dead. [1] And so the pair continue north, through the Lake District to Edinburgh and beyond:

We left Edinburgh in a week, passing through Coupar, St Andrews, and along the banks of the Tay, to Perth, where our friend expected us. But I was in no mood to laugh and talk with strangers, or enter into their feelings or plans with the good humour expected from a guest; and accordingly I told Clerval that I wished to make the tour of Scotland alone. [2]

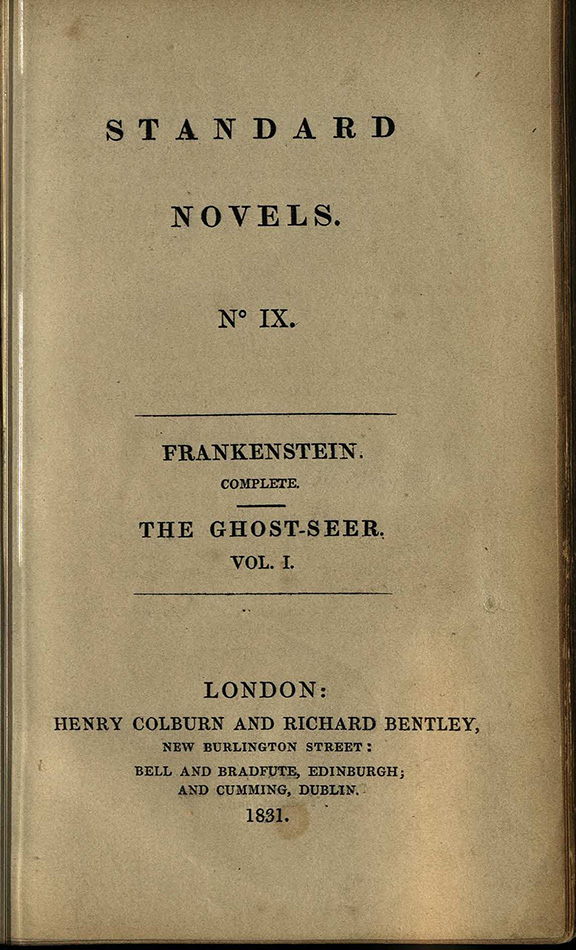

St Andrews joins Oxford and Ingolstadt in the novel’s triumvirate of university towns because Shelley knew Fife well. Like Frankenstein she travelled into Scotland alone, when her father William Godwin sent her to stay with his friend William Baxter and his two daughters in Dundee in the summer of 1812. She was fifteen and Godwin already thought that his daughter had ‘considerable talent’, as he informed Baxter, hoping that she would be ‘exited to industry’ in her new Scottish surroundings. [3] The trip had the desired effect. As Shelley recalled later, it was ‘on the blank and dreary northern shores of the Tay, near Dundee’ that she first began to write. ‘[B]eneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, […] my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered’. [4] By 1831, when these recollections were set down as part of her introduction to a new edition of the novel for Richard Bentley’s Standard Novels series, Shelley had come to see Scotland as a deeply creative place. In Frankenstein Victor’s reasons for choosing ‘some obscure nook in the northern highlands of Scotland’ for the assembly of a second creature are never fully explained, but his ability to set to work in the barren rocky environment of the Orkney isles suggests that he too is able to harness some of the creative power that Shelley found in the bleak sides of the mountains surrounding the Tay. [5]

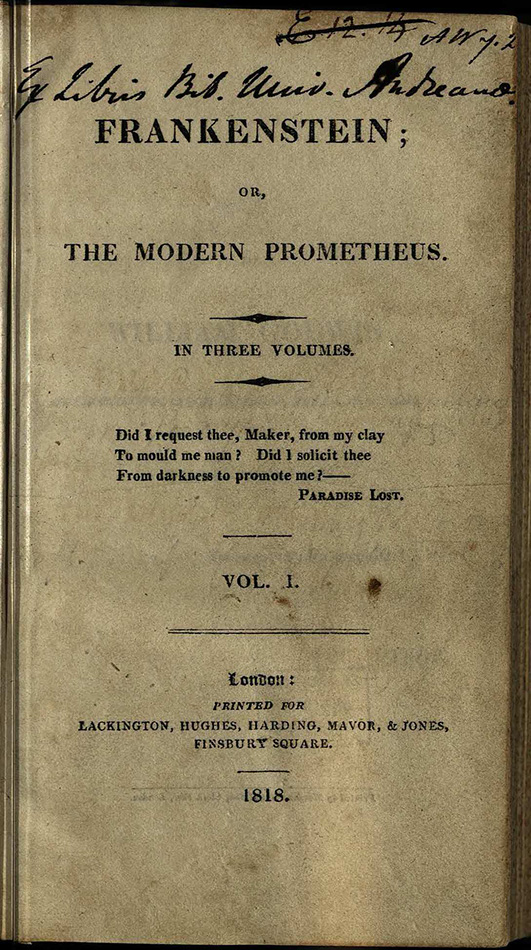

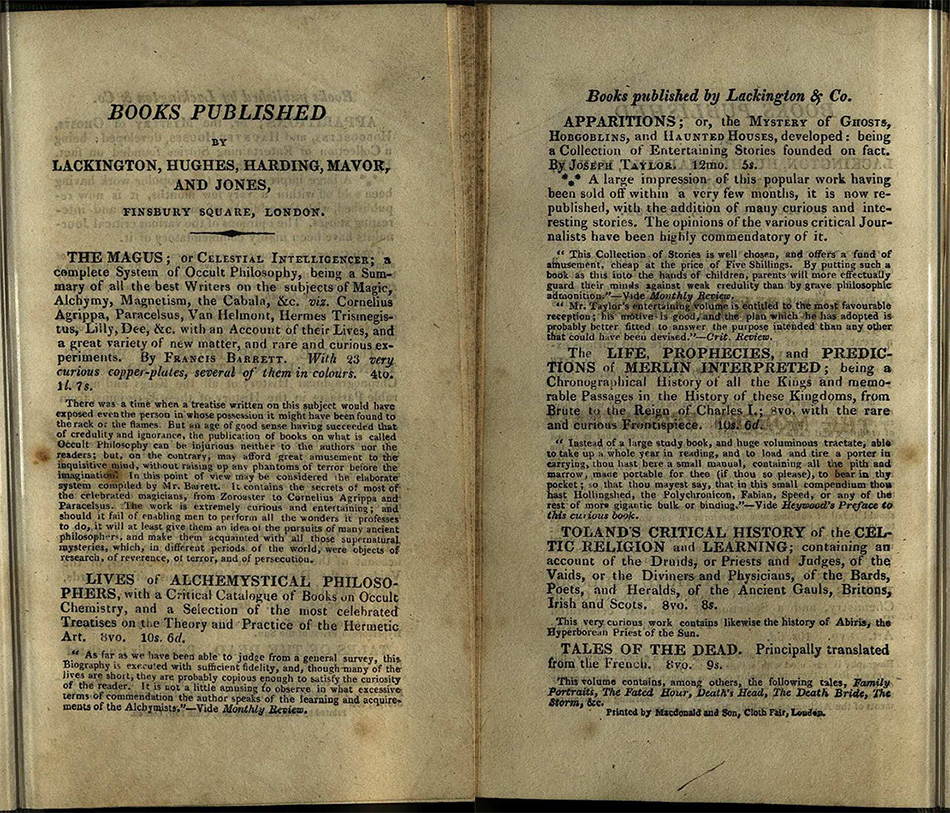

Shortly after Shelley brought Frankenstein to St Andrews, one of the 500 first edition copies also made the journey north from London to Fife following the novel’s publication by Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, and Jones on 1 January 1818. Acquired from Stationer’s Hall under the terms of St Andrews’s copyright licence, it is a remarkably clean copy, apparently only picked up by a few interested undergraduates from the 1830s onwards, and bound with the publisher’s original advertisements at the end of the first volume. [6] William St Clair first drew attention to how the contents reveal Lackington’s fringe position in the publishing market as promoters of ‘magic, the illegitimate supernatural, and horror’. [7] The six titles from Lackington’s back catalogue offer a curious secondary reading list for Frankenstein’s first readers, several of which appear to contain precisely the kind of ‘supernatural terrors’, or ‘mere tale[s] of spectres and enchantment’ that Percy Shelley sought to distance Frankenstein from in the preface he penned for the novel. [8]

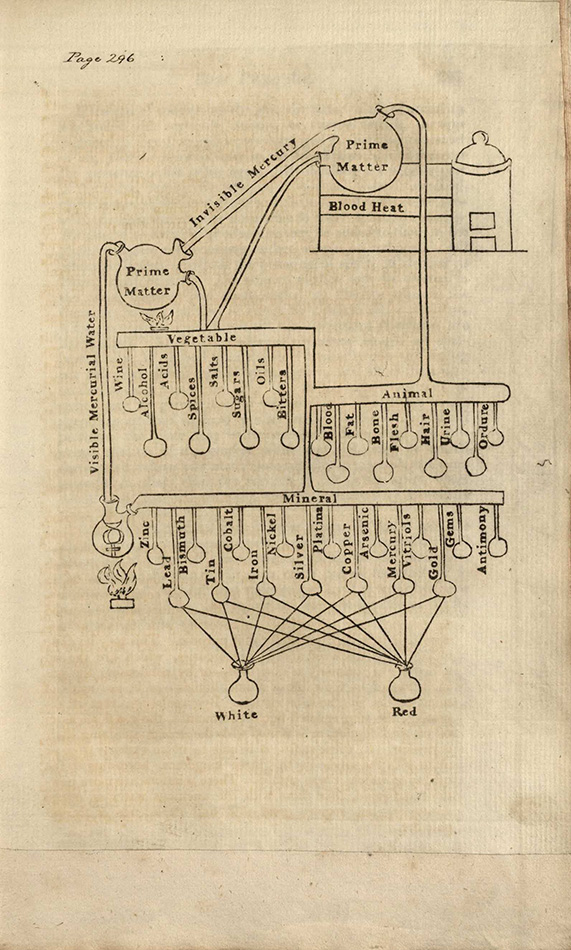

Francis Barrett’s The Magus; or Celestial Intelligencer (1801) is marketed as nothing less than ‘a complete System of Occult Philosophy’, including ‘Magic, Alchymy, Magnetism’ and ‘the Cabala’. Promoted by Lackington’s for its discussion of Cornelius Agrippa and Paracelsus, it promises to expose ‘all those supernatural mysteries, which, in different periods of the world, were objects of research, of reverence, of terror, and of persecution’. Before he begins to work on the creature, animated via a ‘spark of life’ that has increasingly been interpreted as electric and scientific, Frankenstein is inspired by his reading of Agrippa, Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus to conduct experiments in the more occult realm of ‘raising of ghosts and devils’ (p. 24), and vibrant red devils and demons look out from the ‘very curious copper-plates’ in The Magus. The Lives of Alchemystical Philosophers, with a Critical Catalogue of Books in Occult Chemistry (1815), also by Barrett, provides a biographical introduction to some of Victor Frankenstein’s favourite authors, a bibliography of 751 relevant works, and extracts of key alchemic treatise, including instructions for how to make a resurrection stone for any wayward contemporary readers who might wish to follow in Frankenstein’s footsteps. But Lackington and Co. are keen to point out that such books are historical and intellectual curiosities rather than dangerous works for emulation in the current ‘age of good sense’, where enlightened, rational minds will not permit the ‘raising up of any phantoms of terror before the imagination’.

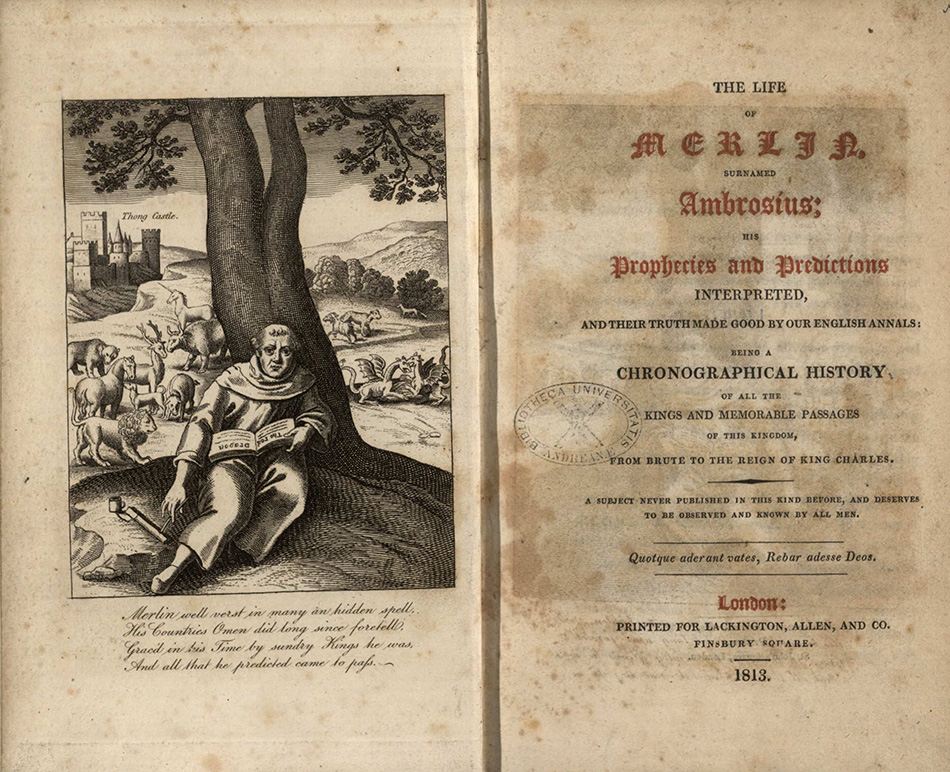

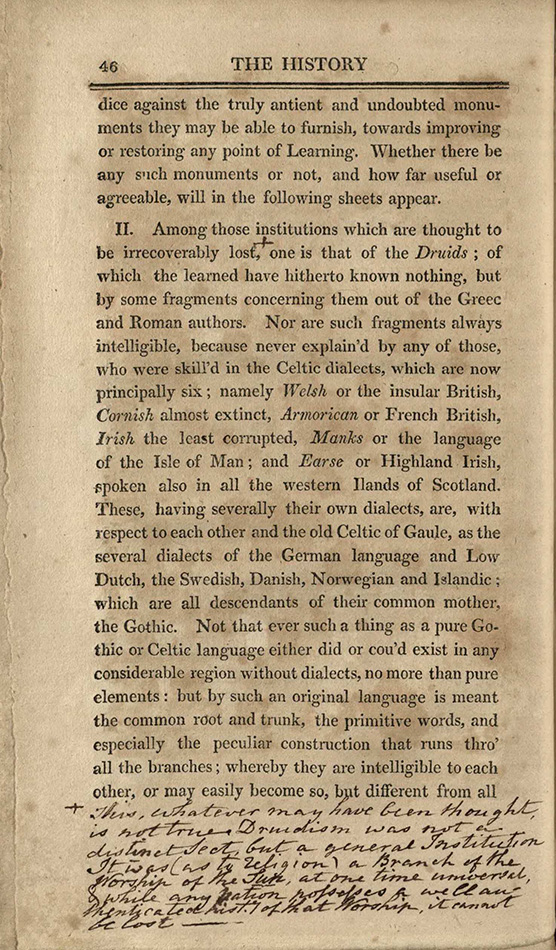

Having promoted two study books on alchemy, the publishers turn to the supernatural section of their list with Joseph Taylor’s Apparitions: or, The Mystery of Ghosts, Hobgoblins, and Haunted Houses, Developed (1815). Modern day enlightenment from superstition is again emphasised in Taylor’s anthology, containing stories ‘founded on fact, and selected for the purpose of eradicating those fears, which the ignorant, the weak, and the superstitious, are but too encourage’. Taylor’s mission is nothing less than to ‘undeceive the world’ by revealing the rational explanation for apparently supernatural encounters, and his approach somewhat proto-Freudian in its emphasis on the lasting influence of stories of ghosts and phantoms heard in childhood; the anthology, he claims, will be ‘an antidote against a too credulous belief in every village tale, or old gossip’s story’. [9] In contrast, Thomas Heywood’s more equivocal The Life of Merlin, Surnamed Ambrosius (1813), reprinted from 1641, leaves the supernatural unexplained. Heywood accommodates both the magical and the mundane in his account of the birth of Merlin, the son of a woman and a ‘fantastical spiritual creature, without a body’, which ‘may easily be believed to be mere fiction, or excuse to mitigate her fault […] And yet we read that other fantastical congression is not impossible’. [10] For Heywood, Merlin’s ability to bring about ‘the resurrection of the dead to new life’ is consistent with the ‘orthodoxical Christian faith’, and engaged in the same act of resurrection, Frankenstein is a kind of modern day Merlin. [11] The Romantic interest in the Celtic world and Britain’s ancient past, as part of the broader medieval revival, is evident in Lackington’s decision to revive Heywood’s seventeenth-century text, as well as John Toland’s A Critical History of the Celtic Religion and Learning from 1740. In Frankenstein, Shelley gives a version of this passion to Henry Clerval, whose ‘favourite study consisted of books of chivalry and romance’. [12] Toland describes how ‘the Druids were commonly wont to retire into grots, dark woods, mountains and groves’ and mentions the evidence for druid temples in Orkney, echoing Frankenstein’s withdrawal from society to those islands for his secret toil. [13] The St Andrews copy contains substantial annotations by Nathan Philipps that provide some forthright corrections to Toland’s findings as well as supplementary references.

But the last book on Lackington and Company’s list has perhaps the closest connection to Frankenstein. Sarah Utterson’s Tales of the Dead (1813) is an English translation and revision of Jean-Baptiste Benoit Eyriès’ continental ghost story collection, Fantasmagoriana; ou recueil d’histoires d’apparitions de spectres, revenans, fantomes, etc (1812). Eyriès was himself translating German ghost stories into French, and the complex chain of translation and reconfiguration surrounding Fantasmagoriana emphasises how deeply Romantic Gothic writing is underwritten by European exchanges. Maximilliaan van Woudenberg has traced the connections between the original German tales, Eyriès’s collection, and Utterson’s in detail in an excellent series of blog posts for Romantic Textualities. Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, Byron, and his physician John Polidori read Eyriès’s collection when confined to Byron’s rented villa in Geneva by the wet and stormy weather in the summer of 1816. Byron subsequently proposed that they ‘each write a ghost story’, and, after dreaming of ‘a pale student of unhallowed arts’ animating a ‘hideous phantasm of a man’, Shelley began to write Frankenstein, first as a ‘short tale’. [14] Mary Shelley’s first readers would not have known of the intertextual connection between Utterson’s Tales of the Dead and the novel in their hands, as Percy Shelley’s introduction to the 1818 edition simply mentioned ‘some German stories of ghosts’ read in Geneva. Details of the stories Shelley remembered hearing were only revealed later in her 1831 ‘Introduction’ to the novel. Perhaps Lackington and Co. were made aware of the association by Percy Shelley, but there is no surviving evidence to prove it. The spectral presence of Fantasmagoriana in Frankenstein – not fully present but there in its paratextual advertisements; not the same text that Shelley read and heard, but a translated version – is a peculiarly Gothic coincidence.

Dr Katie Garner

School of English

[1] Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, ed. Marilyn Butler (1818; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 133; p. 137.

[2] Shelley, Frankenstein, ed. Butler, p. 135. Mary Shelley corrected the spelling of Coupar to Cupar in an annotated 1818 copy now held at Pierpoint Morgan Library. See Charles E. Robinson, ed. The Frankenstein Notebooks: Part 2 (1996; Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), p. 465.

[3] William Godwin to William Thomas Baxter, 8 June 1812. In Shelley and His Circle 1773-1822, ed. Kenneth Neill Cameron and Donald H. Reiman (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961-73), vol. III, pp. 100-102.

[4] Mary Shelley, ‘Introduction’ to Frankenstein (London: Bentley, 1831), p. vi.

[5] Shelley, Frankenstein, ed. Butler, p. 136.

[6] For this information I am indebted to Stacie Bradly, Laidlaw Intern 2017, who tracked the readership of Frankenstein in the library borrowing records part of her project on Jane Austen’s readership in St Andrews. William St Clair notes that the advertisements are also preserved in the copy in Codrington Library, All Souls Oxford. See St Clair, The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 359.

[7] St Clair, The Reading Nation, p. 359.

[8] [Percy Shelley], ‘Preface’, Frankenstein, ed. Butler, p. 4.

[9] Joseph Taylor, Apparitions; or, The Mystery of Ghosts, Hobgoblins, and Haunted Houses, Developed, 2nd ed. (London: Lackington, Allen, and Co., 1815), p. viii.

[10] Thomas Heywood, The Life of Merlin, Surnamed Ambrosius; His Prophecies and Predictions Interpreted (London: Lackington, Allen, and Co., 1813), p. 40.

[11] Heywood, The Life of Merlin, p. 44.

[12] Shelley, Frankenstein, ed. Butler, p. 21.

[13] John Toland, A Critical History of the Celtic Religion and Learning (London: Lackington, Hughes, Harding and Co., n. d.), p. 61.

[14] Mary Shelley, ‘Introduction’, Frankenstein (London: Bentley, 1831), pp. x-xi.