In the beginning was the chase

The next of our Visiting Scholar 2018 reports is from José Luís Neves, Lecturer in Photography at Ulster University. In this report José shares with us his highlights from this summer’s visit to St Andrews – one of the photographic albums in the Library’s Special Collections.

The encounter…

The discovery of the beautiful photographic album examined in the following paragraphs was somewhat serendipitous. This unassuming volume was brought to my attention by Rachel Nordstrom, Photographic Collections Manager at St Andrews, during a conversation about storytelling and the creation of photographic narratives in book form. She felt that the narrative in this early photographic album fitted my description of ‘photobookwork’ practice, that is, a codex in which photographs are used to create a cumulative and multi-layered visual narrative that traverses the whole book.

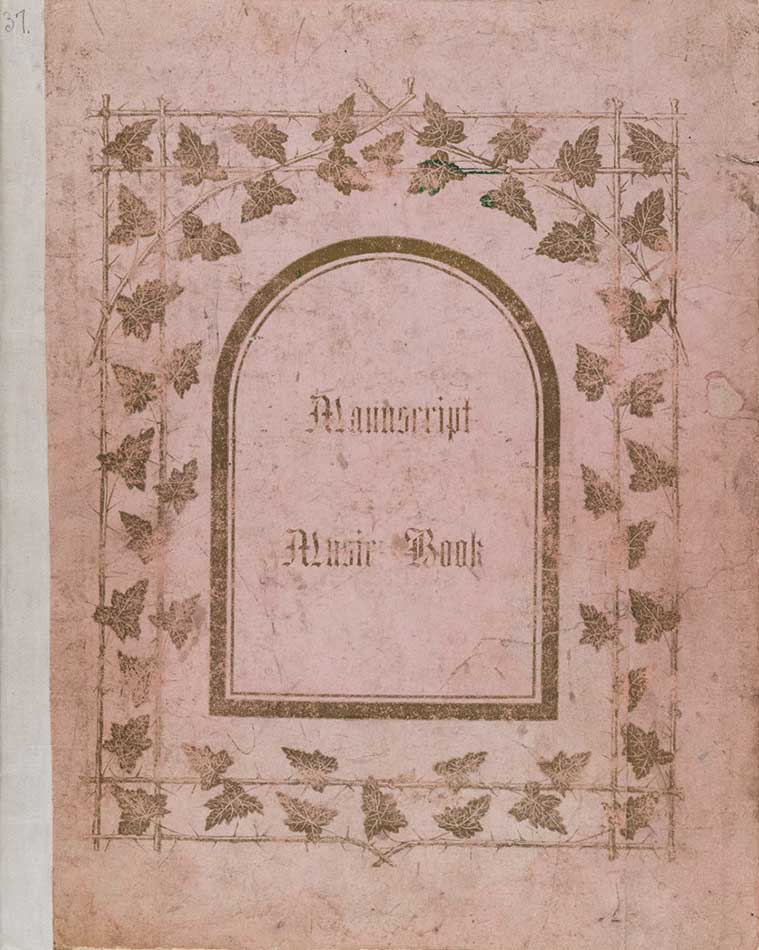

In fact, ‘General Album 37’, seems to be one of the earliest examples – if not the earliest – of such a practice. Instead of musical notation, this ‘music book’ contains a visual and verbal representation of a love story. Its six calotypes and accompanying poems and titles, attributed to Scottish photography pioneer John Adamson and presumably produced in the mid-1840s1, establish a narrative by using what Robert Massin calls le contrepoint. A form of mise-en-page that creates a structural tension based on the juxtaposition of several photographic images and series. Importantly, as noted by Massin:

This pursuit (fuga), this chase (caccia) of a subject by another subject, … does not disturb, cancel or destroy any of the subjects. Instead, it generates reciprocity, clarification, development, systematisation, interweaving, overlapping, and amalgamation. It creates relationships, proposes connections, establishes correlations, develops subordination, suggests analogies and confirms affinities.2

Although not a book in the strict sense of the term, since it was not intended for publication, this modest album embodies the key characteristics of photobookwork practice as defined by Alex Sweetman in the mid-1980s, namely the ‘inter-relationship between two factors: the power of the single photograph and the effect of serial arrangements in book form’.3 In fact, this brief visual and verbal polyphony signals the beginning of a complex and lengthy path towards the full development of cumulative and relational visual narratives in book form.4

The story…

The building blocks of ‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ are its photographic images and the textual elements (titles and handwritten quatrains) that accompany those pictures. To form closure, or to understand the story that traverses the album, the reader/viewer must establish connections between the six tableaus that compose the primary track of this album while simultaneously relying on the anchoring nature of the poems to amplify, as noted by Roland Barthes, ‘a set of connotations already given in the photograph’.5

The first tableau in ‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ (Figure 2, above) sets the emotional tone of this short story. We are told in its title and stanza that the melancholic expression of the young lady, her ‘pensive mood’, is caused by her lover’s absence. The plight of the main character is intensified in the following tableau when she is confronted with the presence of a new suitor.

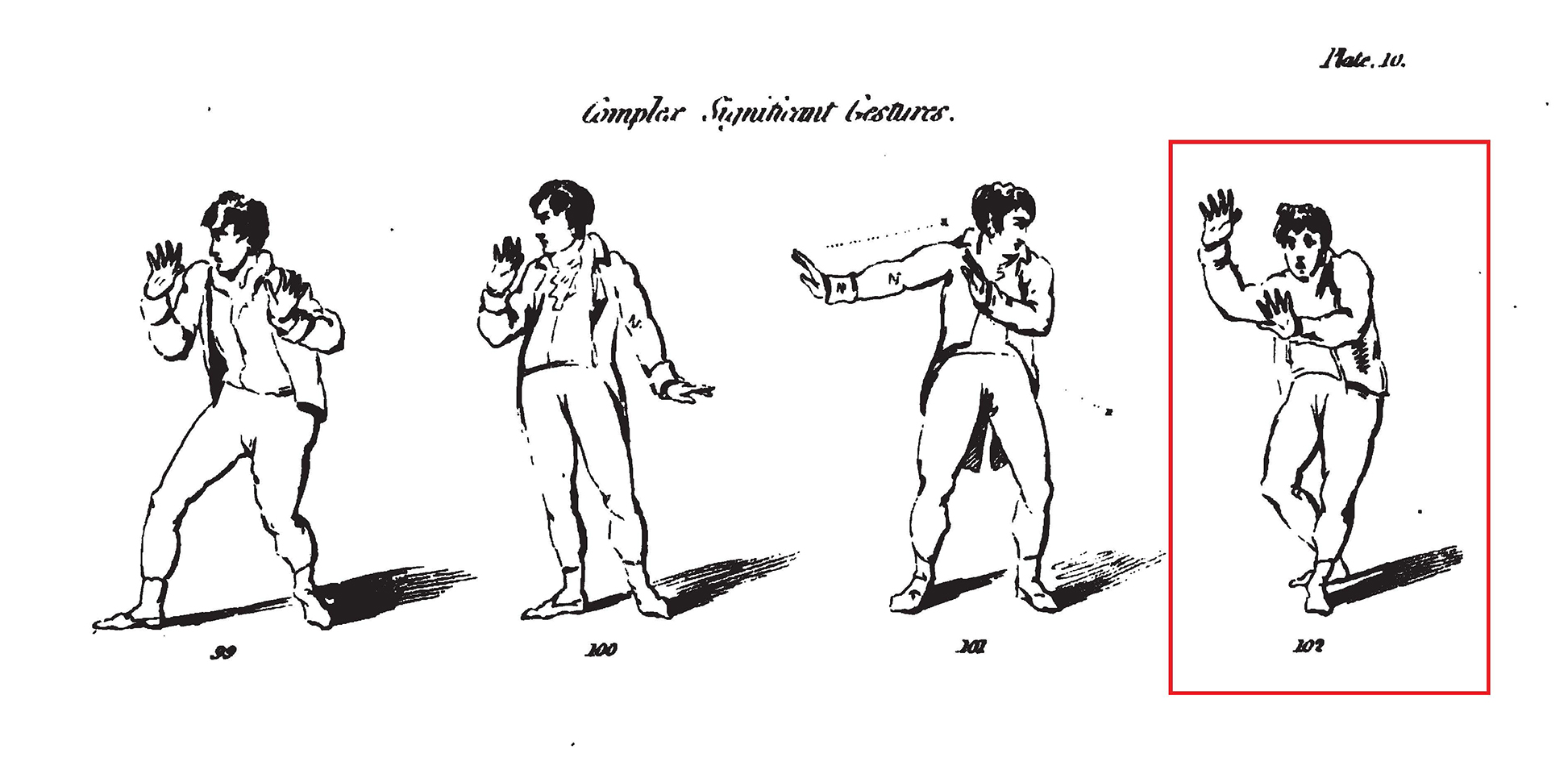

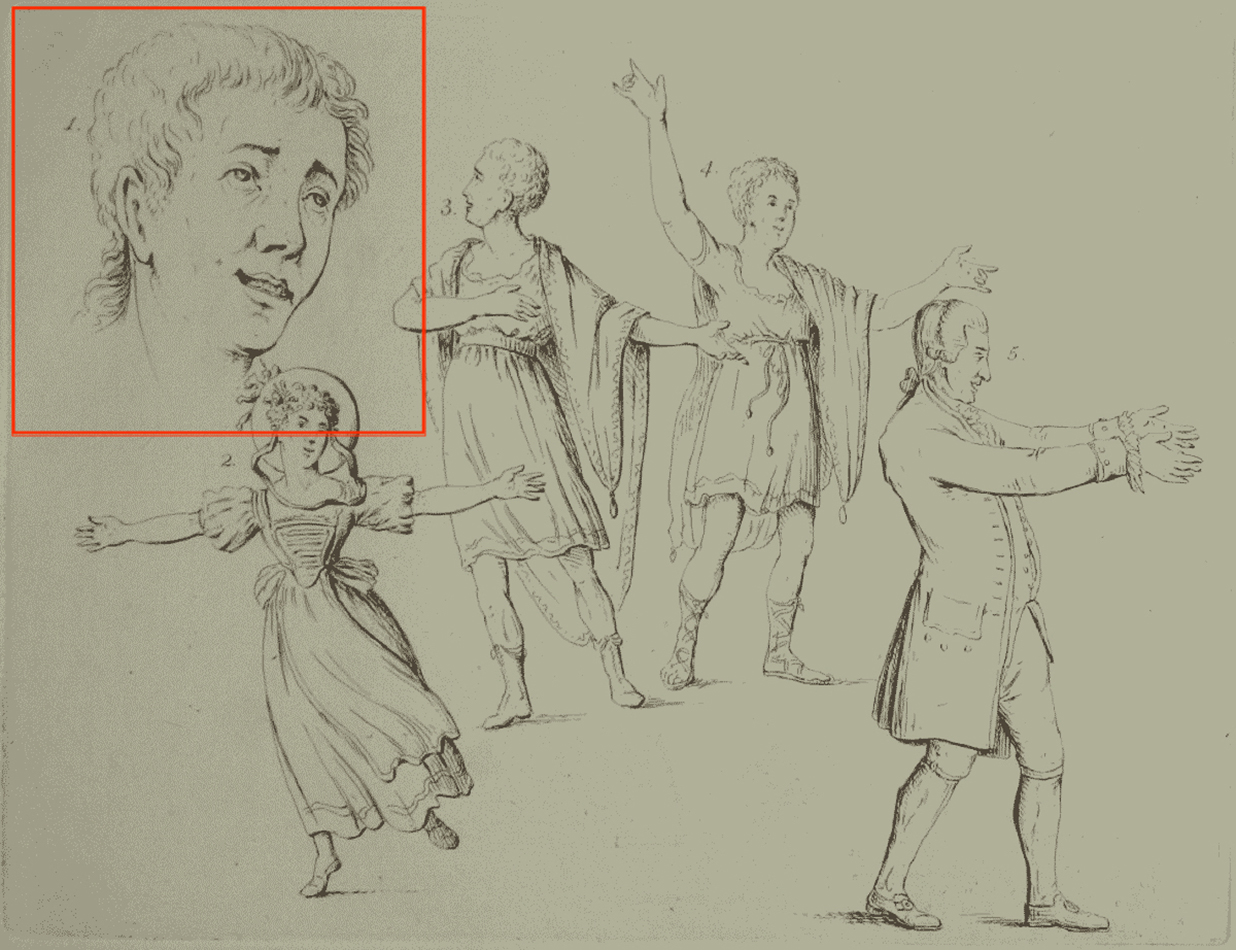

The underlining of the word ‘Horror’ in the quatrain firmly reiterates the vivid and powerful visual depiction of anguish present in the photographic image. Interestingly, the rhetorical gesture staged in this tableau echoes the body language performed in theatre throughout the early 19th century and most likely borrowed from portrait painting. According to Gilbert Augustin’s comprehensive manual on the art of gesture in oratory and acting, this particular emotional state (Horror) is achieved by remaining ‘petrified in one attitude, with the eyes rivetted on its object, and the arm held forwards to guard the person, the hands vertical’6, as demonstrated in Figure 4, below.

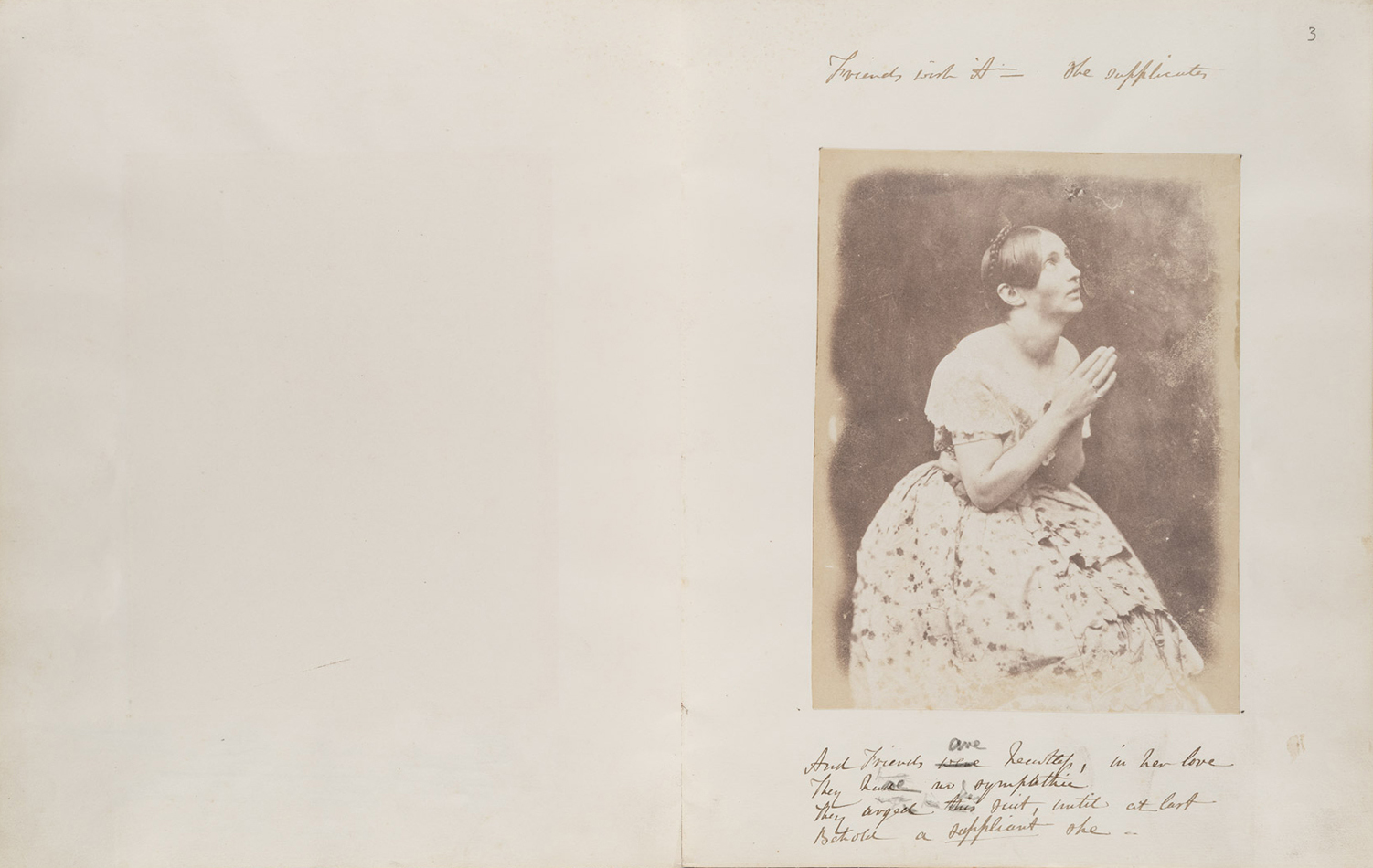

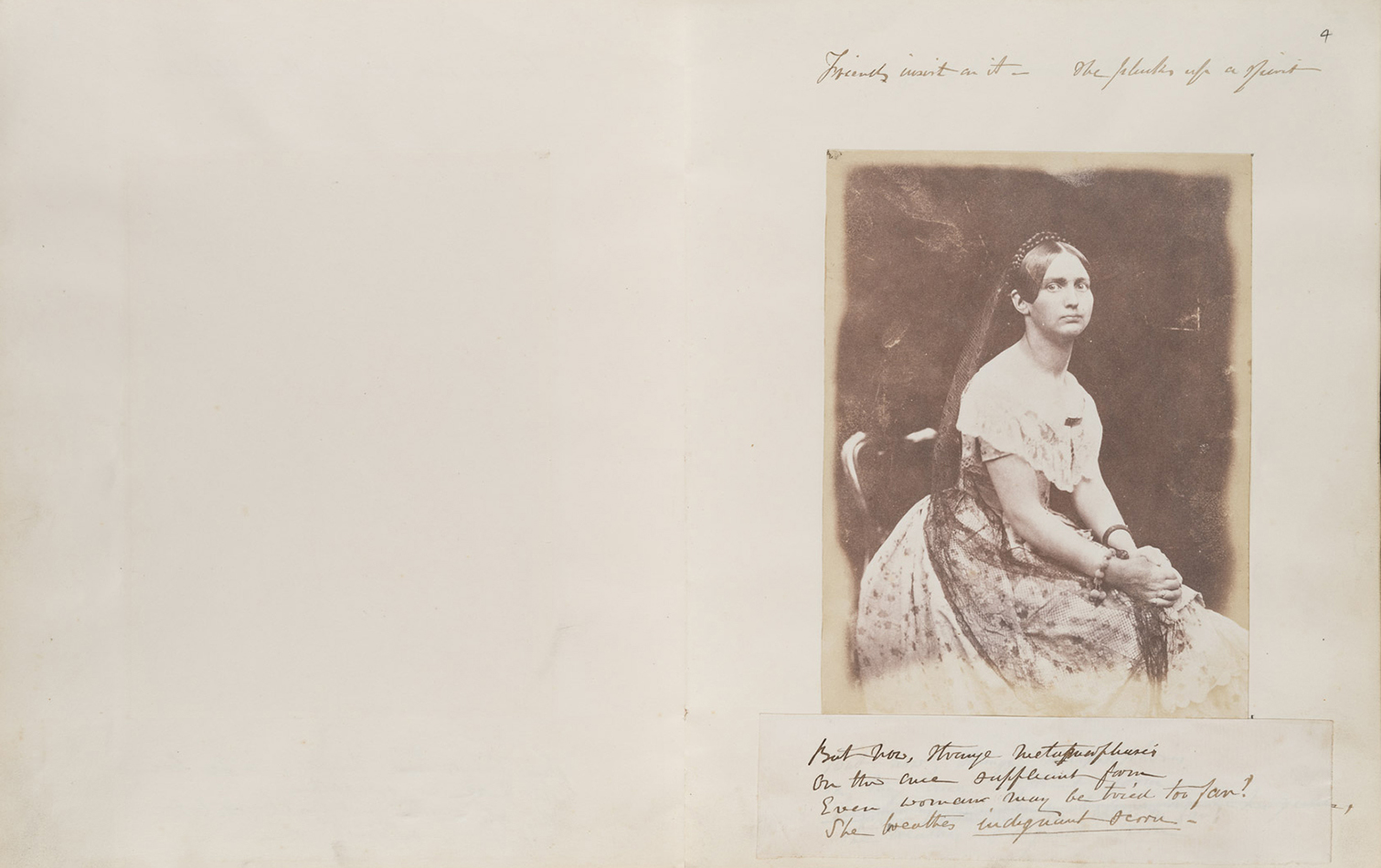

The hand gestures and facial expressions depicted throughout ‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ are crucial for the development of the narrative and help readers/viewers unlock the emotional journey of the character. In Figures 5 and 6 (below), for instance, these rhetorical devices are used to convey an abrupt shift in the character’s emotional state.

While in Figure 5 (above) the young woman remains tormented, a dejection conveyed by her supplicant hands appealing for compassion and acceptance, in Figure 6 (below) her posture is entirely different when compared with the poses performed in the previous tableaus.

This ‘metamorphosis’, as noted in the accompanying stanza, is meant to convey an ‘indignant’ and resolute personality. The young lady’s determined posture and stern face are used to illustrate her readiness to challenge social expectations. She snubs a potential new beau and obstinately waits for the return of her lover.

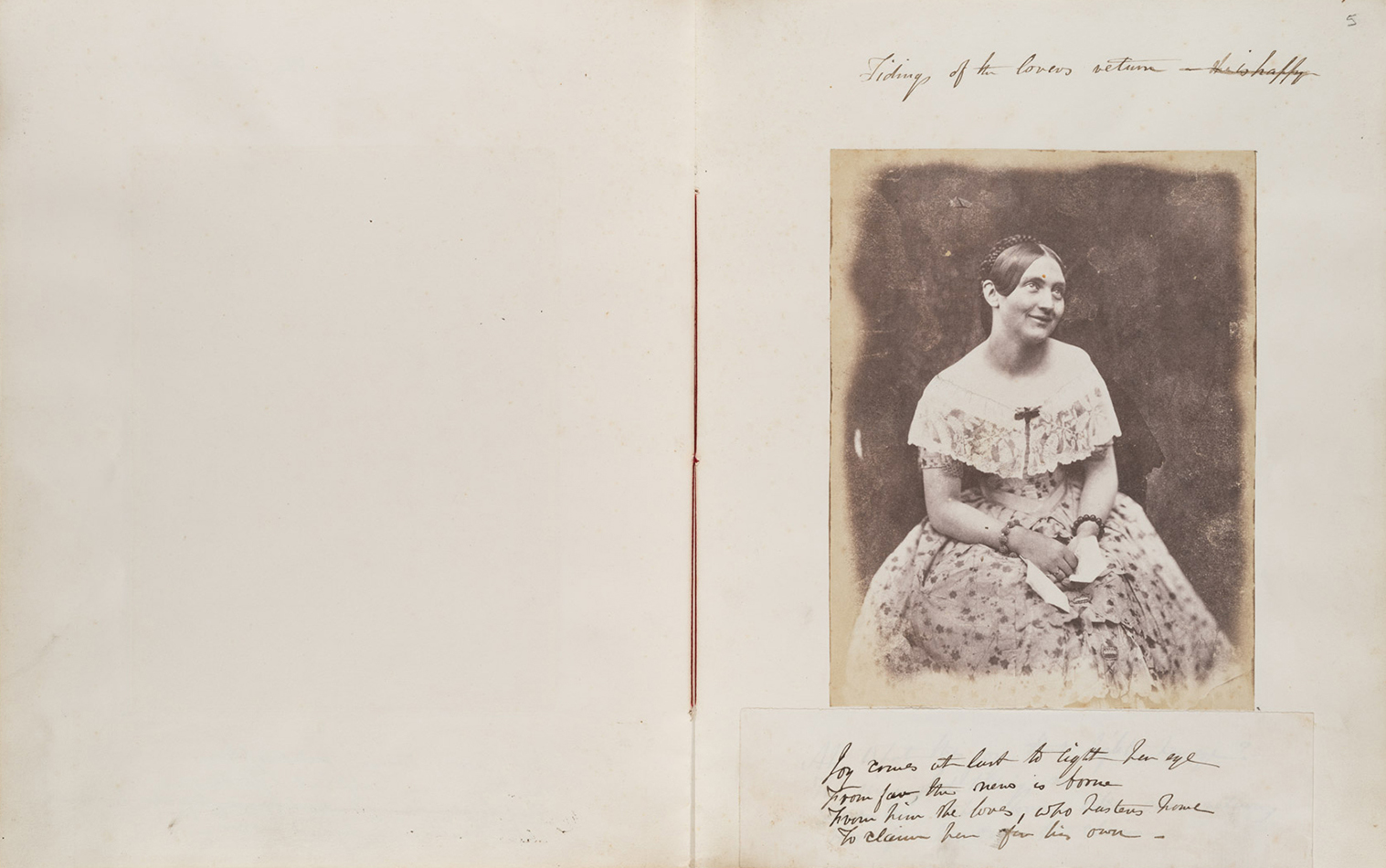

In the following tableau (Figure 7), the young woman’s resolve is rewarded by the imminent arrival of her lover. Clasping a letter that assures her that ‘him she loves … hastens home / to claim her for his own’, the young lady smiles. An expression of joy, the first in this sequence, that once again echoes early 19th-century theatrical rhetoric (see Figure 8, below).

As suggested by Dutch tragedian Johannes Jelgerhuis in Theoretische lessen over de gesticulatie en mimiek, when recreating this particular emotion, the actor should raise the eyebrow softly, the eyes should look heavenly, and the mouth needs to be slightly open with its corners raised.7 Expressions that are unmistakably present in Figure 7.

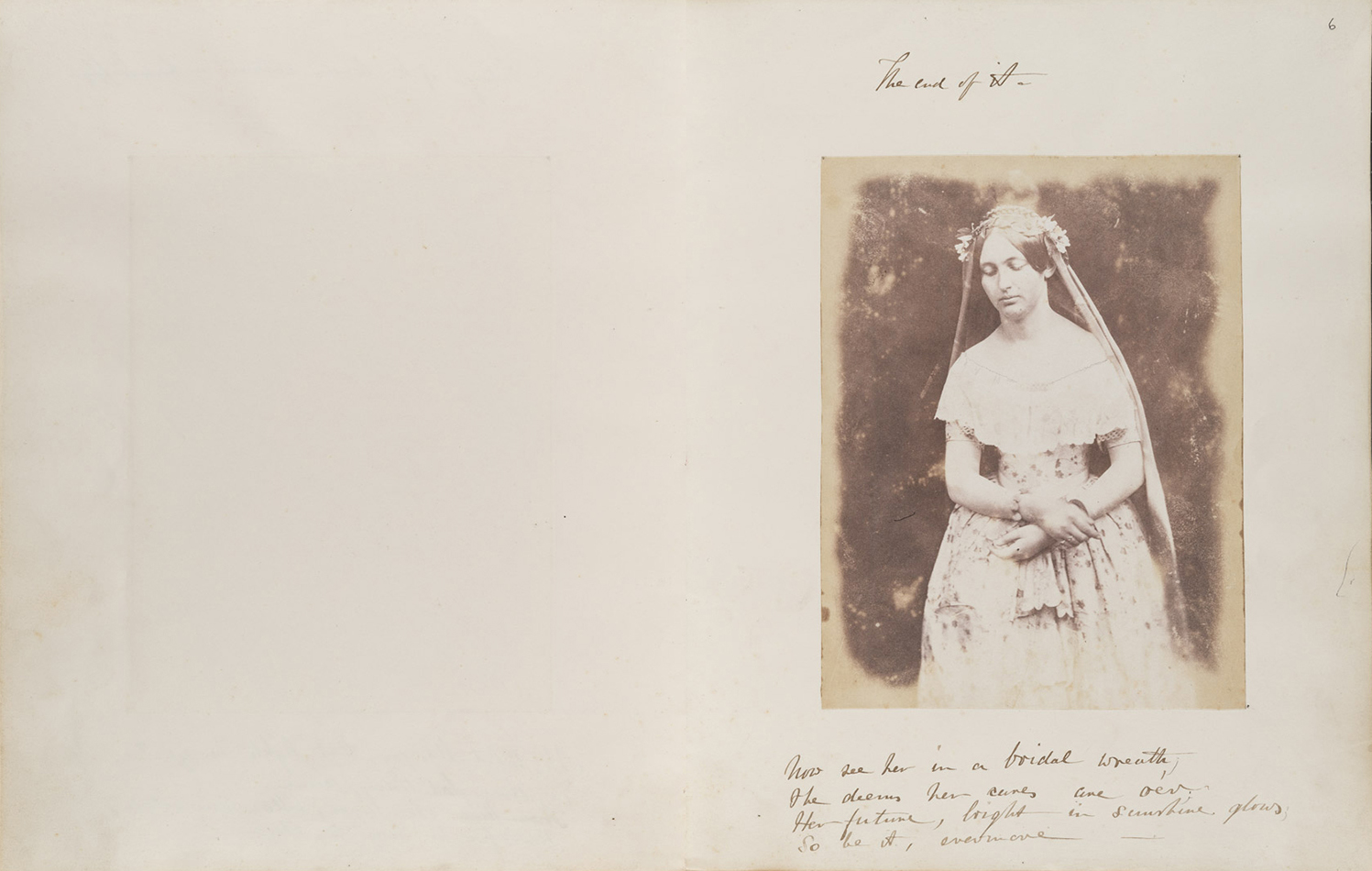

In contrast to the melodramatic poses that precede it, the closing tableau in ‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ (Figure 9, above) represents the expected modesty and poise of a wife-to-be. After her ordeal, the young lady ‘dreams her cares are o’er’ and that ‘her future, bright in sunshine glows.’ The closing nature of this scene becomes obvious not only through its title, ‘The end of it’, but also by the lack of any subsequent tableaus. In fact, this absence of continuity, as noted by Barthes, halts the inherent ‘relation of solidarity’8 that permeates a sequence. There is no consequent, to use the French author’s terminology. The chase is over.

Sequentially ever after?

‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ demonstrates how early photographers seem to have immediately embraced the codex as a vehicle for sequential photographic narratives. More importantly, it also confirms that early practitioners understood that photographic sequences represent a syntax in which, as suggested by Barthes, ‘the signifier of connotation is … no longer to be found at the level of any one of the fragments of the sequence [the single photograph] but at that – what the linguists would call the suprasegmental level – of the concatenation [the sequence]’.9 Surprisingly, the syntactical strategy employed in this album is rarely present in 19th-century photobooks. Since, as noted by Lori Pauli, until the late 19th-century, stories seem to have been mostly told within the boundaries of the single image.10 We can thus say that this absence of cumulative and multi-layered narratives in book form challenges the idea that photobookworks, the ‘specific kind of photobook’11 analysed in Martin Parr and Gerry Badger’s trilogy The Photobook: A History, materialised with the inception of photography. ‘A little story for grown young ladies…’ foreshadows this type of photobook making, but the adequate technological and artistic conditions for its full development would only emerge several decades later.

José Luís Neves, PhD

Lecturer in Photography, Ulster University

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my warmest gratitude to the Special Collections team for their support during my stay at St. Andrews. Their help in assisting me with my research (and on how to avoid seagull attacks!) was truly invaluable. A special thanks to Rachel Nordstrom for showing me ‘‘A little story for grown young ladies…’.

List of References & Footnotes

1- Nott, Michael. Photopoetry 1845-2015, a Critical History (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018), 21–22.

2- Massin, Robert. La mise en pages (Paris: Hoëbeke, 1991), 81.

3- Sweetman, Alex. ‘Photographic Book to Photobookwork: 140 Years of Photography in Publication’, CMP (California Museum of Photography) Bulletin 5, no. 2 (1986): 18.

4- I explore this development at length in my PhD thesis: José Luís Afonso Neves, ‘The Many Faces of the Photobook: Establishing the Origins of Photobookwork Practice’ (Ph.D., Ulster University, 2017), https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=4&uin=uk.bl.ethos.733979

5 – Barthes, Roland. ‘The Photographic Message’, in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 27.

6 – Austin, Gilbert. Chironomia; or, A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery. (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, Printed by W. Bulmer, 1806), 488.

7 – Jelgerhuis, Johannes. Theoretische Lessen over de Gesticulatie En Mimiek (Amsterdam: P. Meyer Warnars, 1827), unpaginated, https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jelg001theo01_01/colofon.php.

8 – Barthes, Roland. ‘Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative’, in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977), 101.

9 – Barthes, Roland. ‘The Photographic Message’, 24.

10 – Lori Pauli, ‘Setting the Scene’, in Acting the Part: Photography as Theatre, ed. Lori Pauli (London; New York; Ottawa: Merrell Publishers ; National Gallery of Canada, 2006), 16.

11 – Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History, Vol. I (London: Phaidon Press, 2004), 6.