Meet your rare anatomy books

On 21st January we held our first outreach session of the year: Meet your rare anatomy books. This event gave staff and students from the School of Medicine (and a couple of Library Directors!) the chance to view and discuss some of the older anatomical and medical books and manuscripts which we hold in Special Collections.

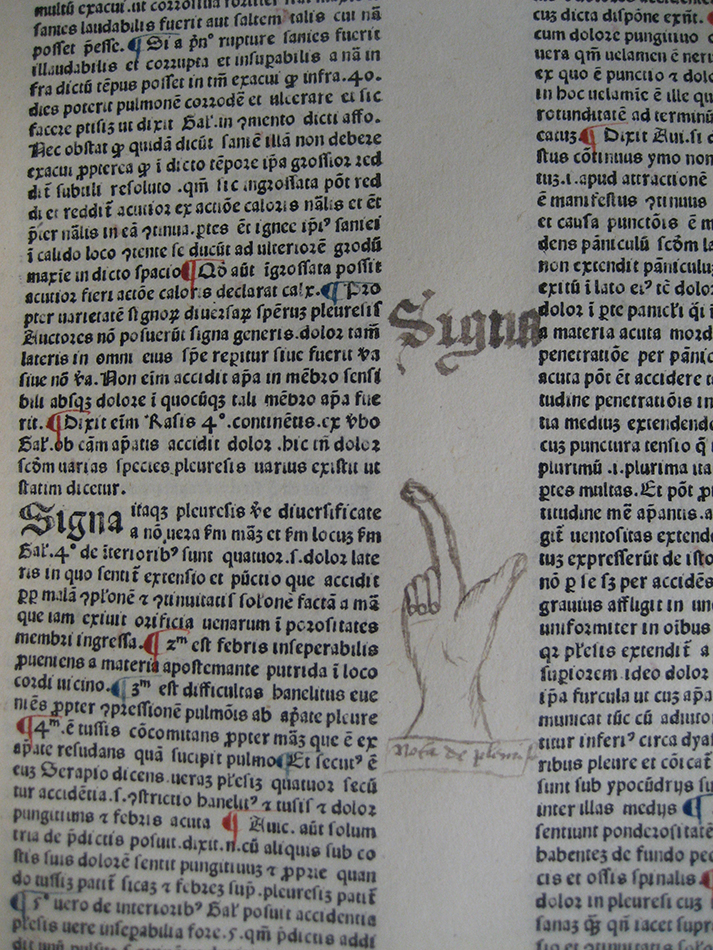

We began in the fifteenth century with Niccolò Falcucci’s (d. 1411/12) Sermones medicinales septem, printed in 1481-84. This volume belonged to William Scheves (d. 1497), Archbishop of St Andrews, and has scarce marginalia throughout, including a large fist pointing to “Signa pleuresis” on leaf h7r. In the early 1470s Scheves received an annual court pension for his services as a physician, but little is known about his medical training. His ownership and annotation of this (and other) medical texts substantiates his interest in this field.

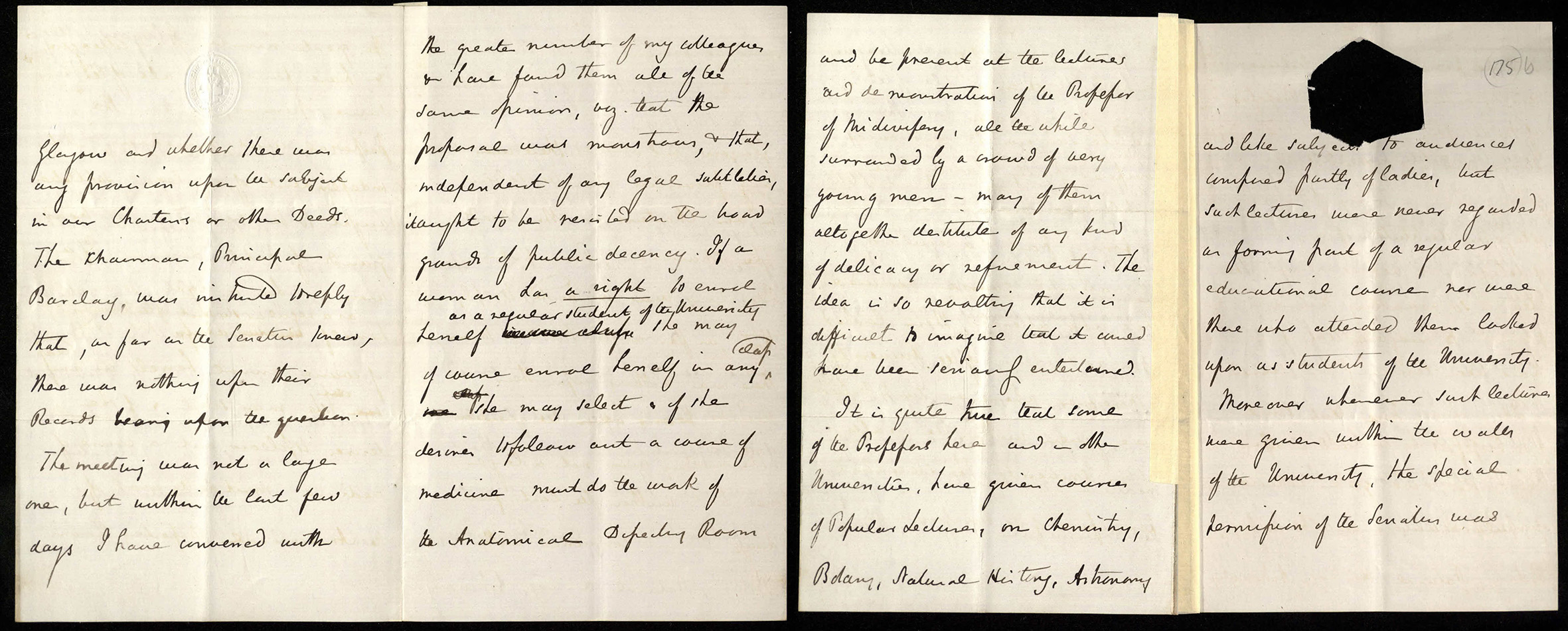

We then toured through the following centuries (with discussions of whether or not a rust coloured mark on a page was blood or foxing), ending in the nineteenth century with a letter of 1862 from William Ramsay (1806-1865), Professor of Humanity at the University of Glasgow, to James David Forbes (1809-1868), Principal of the United College, St Andrews. In this letter Ramsay discussed the attitude of Glasgow University towards female education, in relation to the case of Elizabeth Garrett (1836-1917), who had been allowed to matriculate at St Andrews that year. “I have convened with the greater number of my colleagues and have found them all of the same opinion, viz. that the proposal was monstrous, and that, independent of any legal subtleties, it ought to be resisted on the head grounds of public decency”, for she might, in anatomy classes, “be surrounded by a crowd of very young men – many of them altogether destitute of any kind of delicacy or refinement. The idea is so revolting that it is difficult to imagine that it could have been seriously entertained”. Her name was later scored out from the matriculation register when the Senatus Academicus rescinded her admission.

A repeat session has been requested for the summer. Here are some of the highlights from the event; we hope you enjoy them.

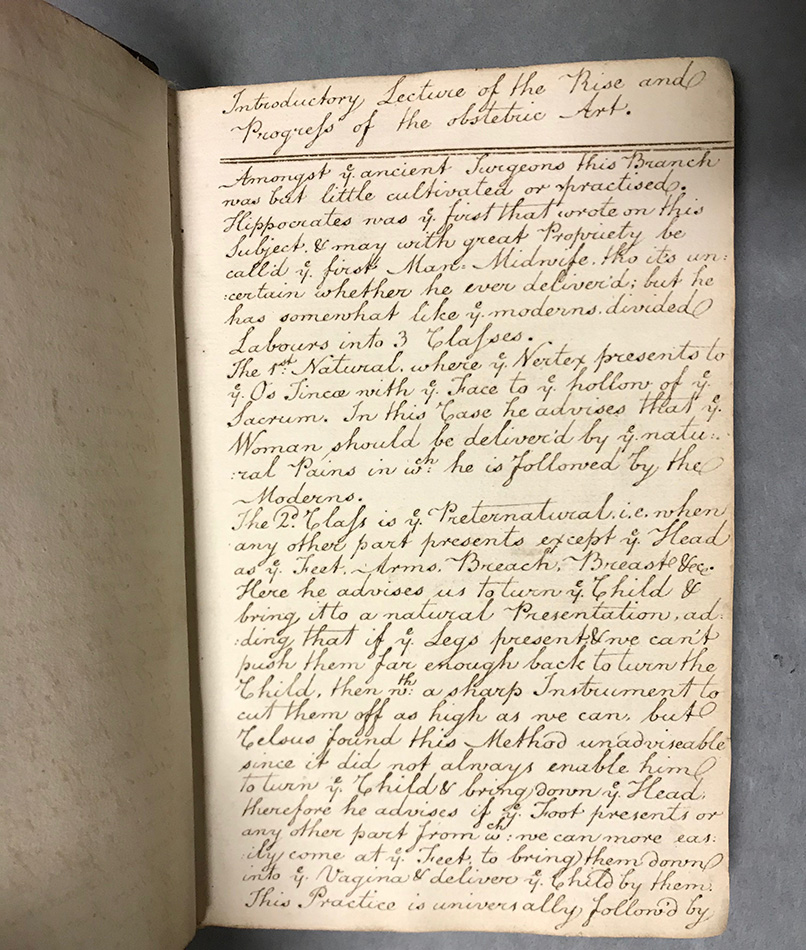

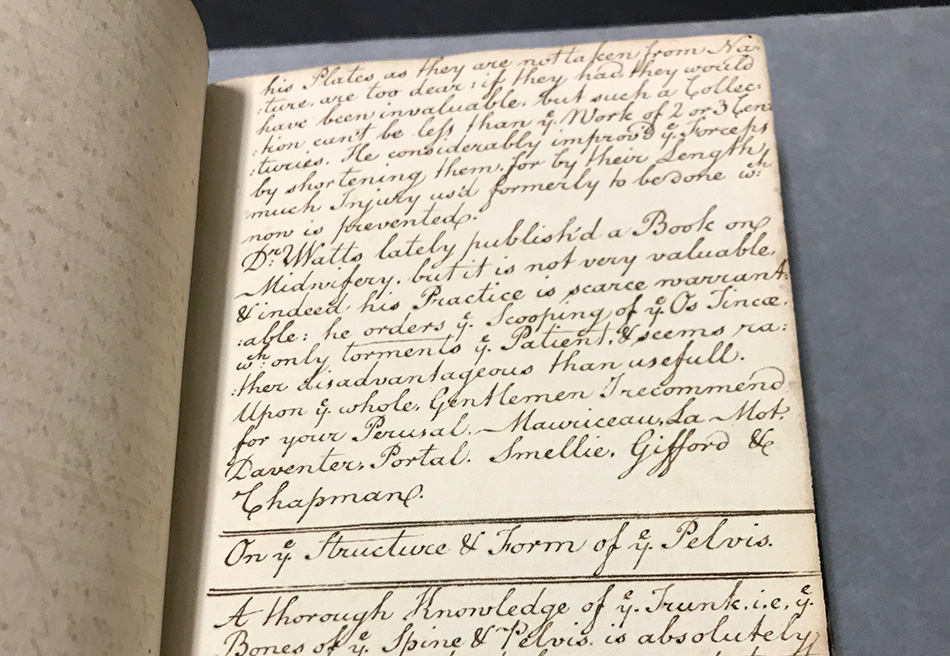

Two manuscript volumes of lectures on midwifery by David Orme (1727-1812) were recently added to our collections, being purchased in July 2018; this is only the second time we’ve had them out on display. Orme was a native of Scotland, who held the office of man-midwife extraordinary to the City of London Lying-in Hospital, and lectured at Guy’s Hospital. There author is not identified within the text itself, but the contemporary labels on the spines are lettered “Orme’s Midwifery”. A rough date to the lectures can be found in the first lecture, where Orme outlines the historical basis of the obstetric art, quoting authors from earlier times up to ‘Dr. Watts’. This is presumably Giles Watts (1725-1792), one of William Smellie’s pupils, and the author of Reflections on Slow and Painful Labours, published 1755. As Orme refers to the works as ‘lately published’, it seems likely his lectures were written c. 1755-1760.

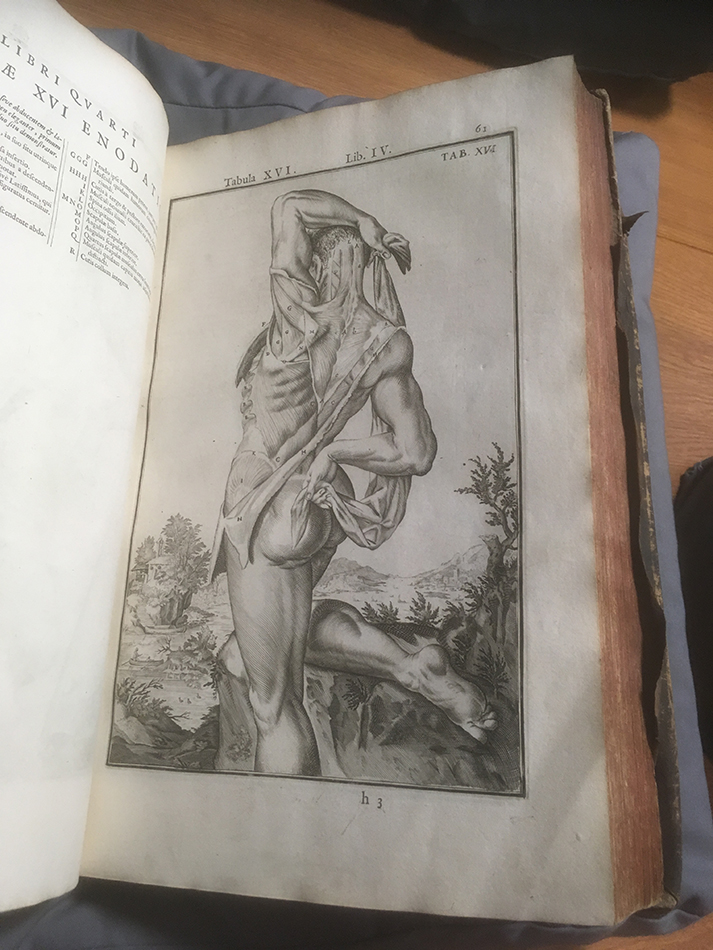

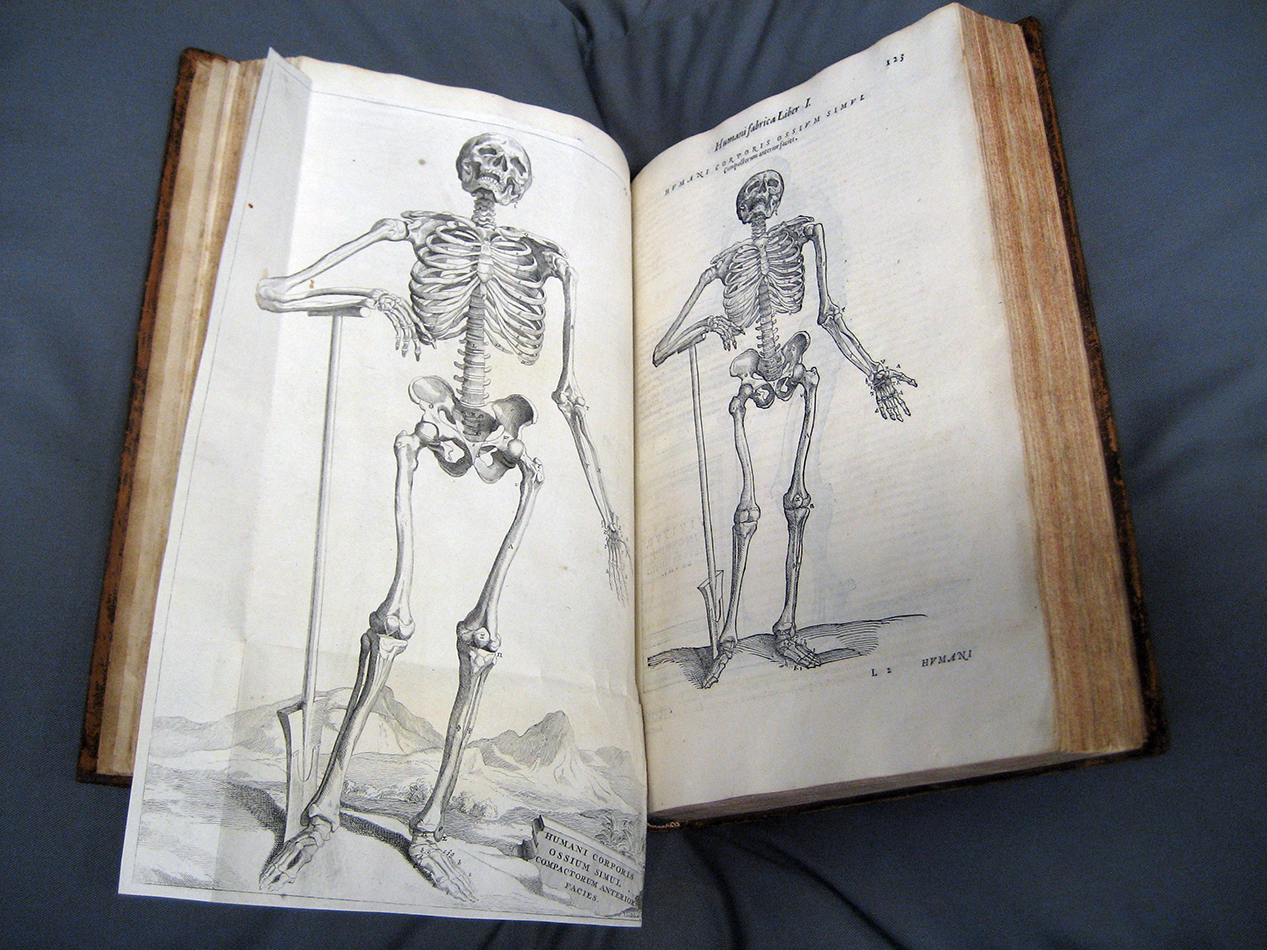

First published in 1543, Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica was a major advancement in the history of anatomy. Prior to the publication of Vesalius’ work, Galen’s (129A.D.-c. 200/216) observation on anatomy had been dominant. Galen had used animal corpses for his observations, but Vesalius used human cadavers, and was thus able to correct some of Galen’s errors. The work is beautifully illustrated with detailed woodcuts. The St Andrews copy includes several larger, more detailed engravings from a copy of Herman Boerhaave‘s edition of 1725 pasted in beside or over the corresponding woodcuts. This copy, published in 1568, belonged to Thomas Simson (1696-1764), the first Chandos Professor of Medicine at St Salvator’s College, University of St Andrews, and it’s therefore possible that he added the larger engravings as an aid to teaching.

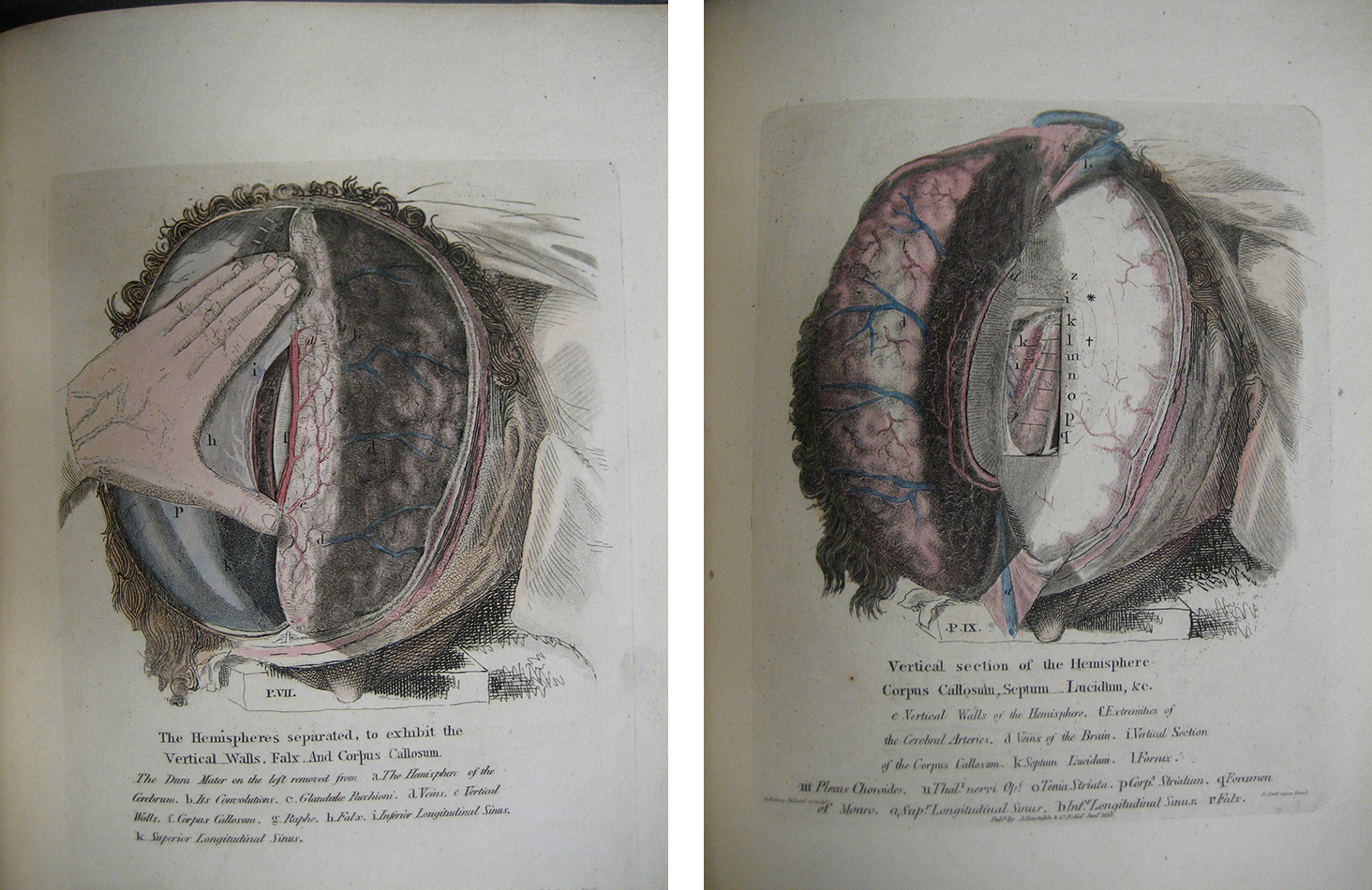

In 1812 Alexander Ramsay (1754?-1824), lecturer on anatomy and physiology in Edinburgh, published his Description of plates of the brain, with direction for the development of that organ by dissection; together with observations on its various parts. “The rapid sale of the first edition of this Work, and the approbation with which it has been received” encouraged Ramsay to publish a second edition the following year, under the title Anatomy of the heart, cranium, and brain …, and it is this edition of which St Andrews has a copy. Ramsay did not trust artists of the day to “adhere so strictly to those minutiæ on which anatomical works become chiefly valuable”, and so he drew the illustrations for the plates himself; they were finished in aquatint by Robert Scott (1777-1841), engraver. Plates VII to XI are particularly ingenuous, for they contain a series of cut-out areas to reveal sections of the plates below, simulating the stages of an actual dissection.

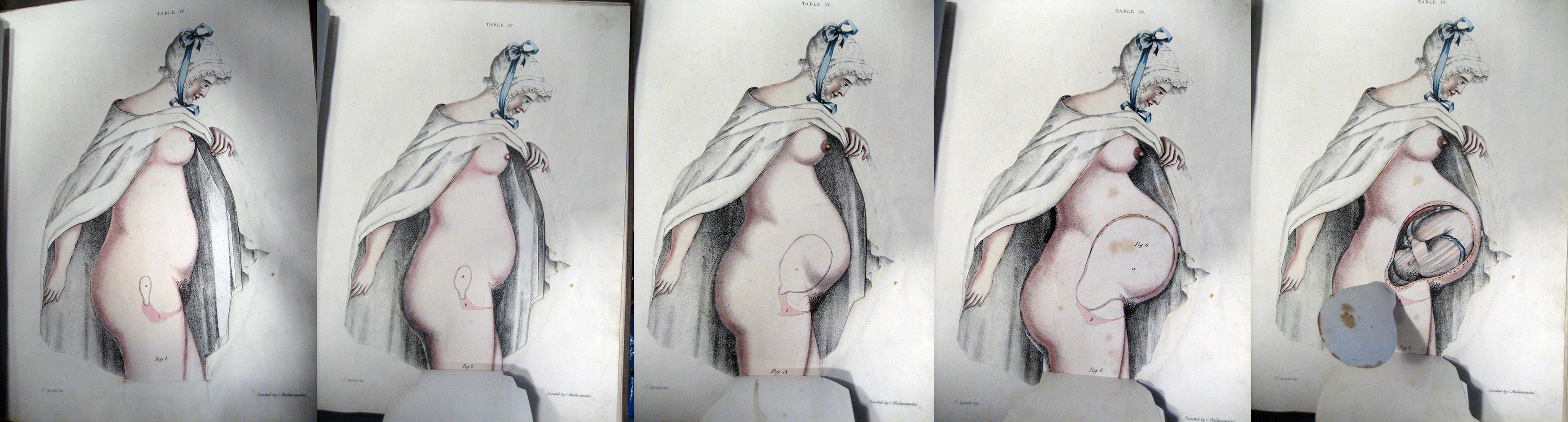

This means of representing spatial relationships in a paper volume is also found in George Spratt’s (1784-1840) Obstetric Tables. First published in 1833 in a single volume, our copy is the third edition, “considerably enlarged and improved”, published in two volumes in 1838. Spratt was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, and describes himself on the title page as “Surgeon-Accoucheur”, that’s to say, a male midwife. The work was intended as a teaching aid, and as such the many colour illustrations have flaps (some as many as four or five layers), offering a ‘3D’ image of the different stages of pregnancy. At a time when it was becoming difficult for medical students to gain clinical experience such an aid would have been invaluable.

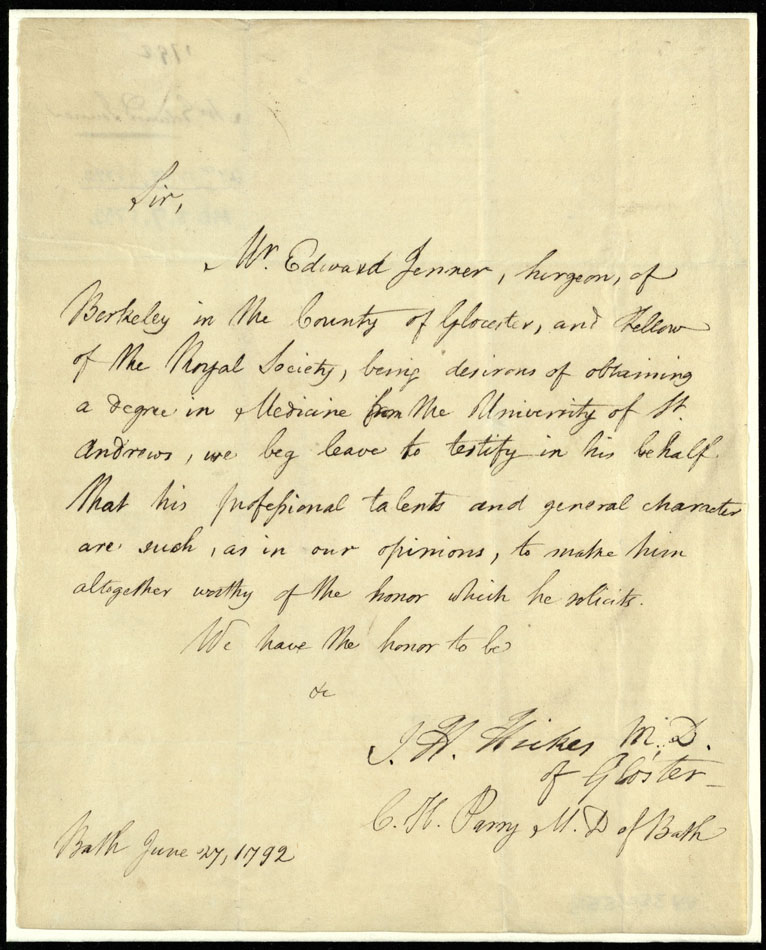

Another of our manuscripts on display was the medical testimonial for Edward Jenner (1749-1823). The University of St Andrews did not offer formal medical training in the 18th century, but rather offered the degree via medical testimonial. In order to obtain a degree from St Andrews someone simply required recommendations from two reputable doctors. Caleb Parry (1755-1822) and John Hickes (d. 1808), Jenner’s colleagues, acted for him in 1792; after twenty years’ experience of general practice and surgery, Jenner could now style himself physician and surgeon.

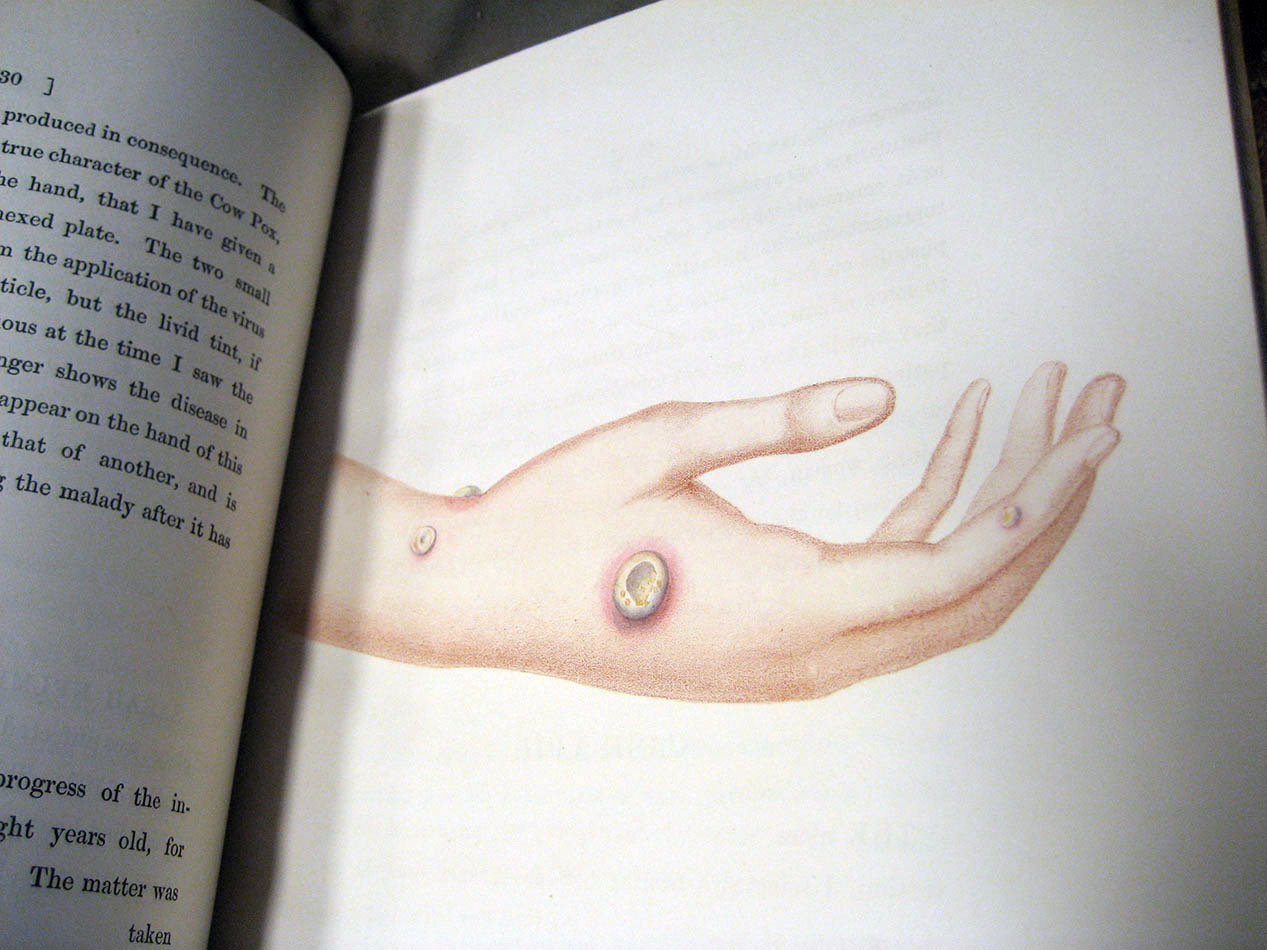

Jenner is famous for inventing the vaccination for smallpox. Testing the theory that milkmaids who suffered with the mild disease of cowpox never succumbed to smallpox, a great killer in the 18th century, in 1796 he carried out the first documented experiment, inserting pus from a cowpox pustule into an incision on 8-year-old James Phipps (1788-1853). The test was successful, but it was another two years, following further testing, before he privately published his results in An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae. St Andrews doesn’t own a first edition of this work, but we brought out our 1884 facsimile reprint of the 1800 second edition.

Briony Harding

Assistant Rare Books Librarian

Elizabeth Henderson

Rare Books Librarian