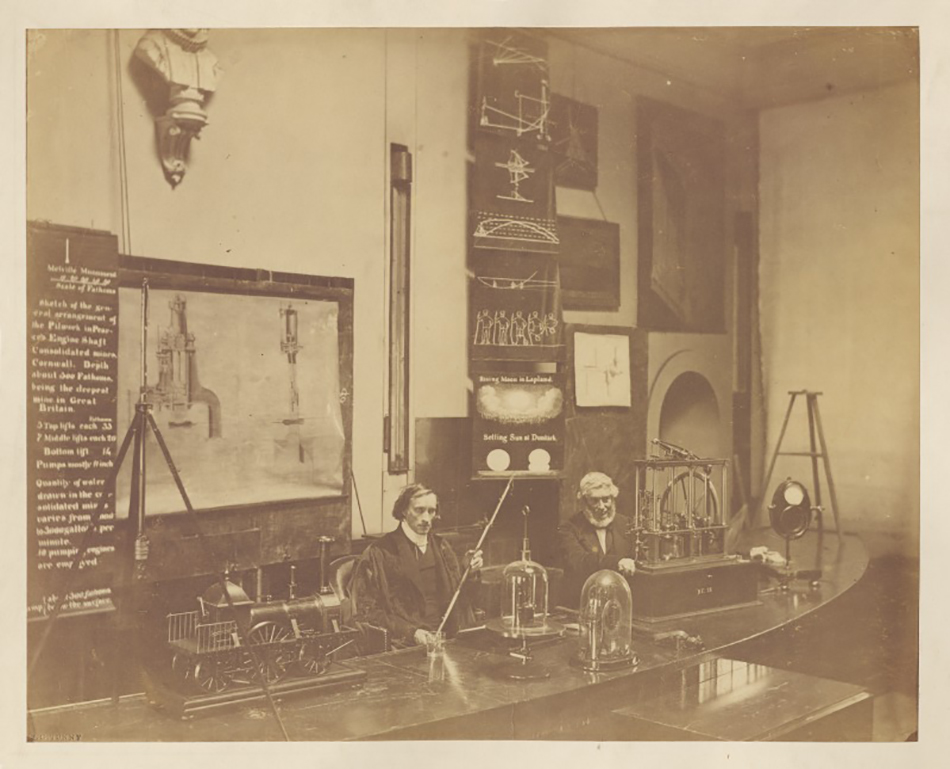

John Ruskin and James David Forbes

Today is the 200th anniversary of the birth of the Victorian art critic John Ruskin (8 February 1819-20 January 1900). Born in London, John Ruskin was the only son of John James Ruskin, a sherry importer and Margaret Cox. A man of many interests, Ruskin is most renowned for his work as an art critic and was appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in 1869. He wrote on a number of topics but is most well-known for his five-volume work Modern Painters (1843-1860) and The Stones of Venice (1851). His contribution to children’s literature in the form of the book Dame Wiggins of Lee and her Seven Wonderful Cats has been highlighted on Echoes in a previous blog.

Ruskin appears in the University of St Andrews record in 1871 when he was voted, by a student majority, Rector of St Andrews. However, the election was found to be invalid due to his ineligibility for the position since he held a chair at Oxford.

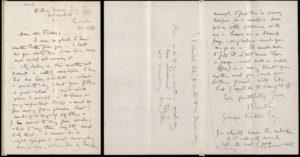

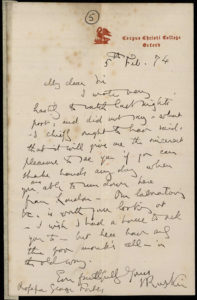

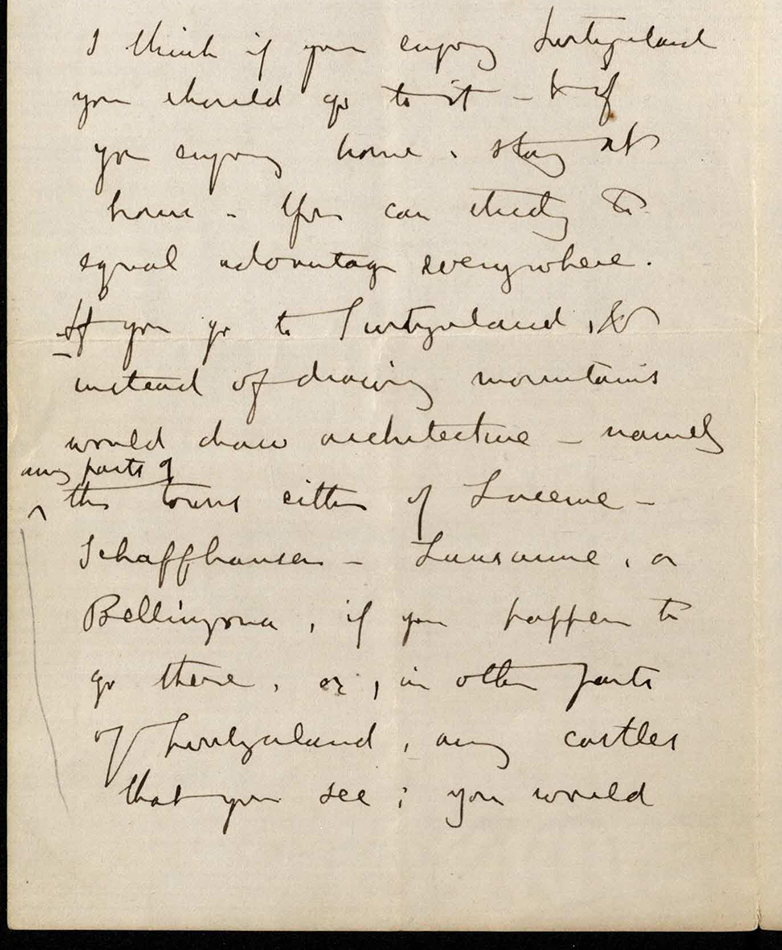

In Special Collections, in addition to copies of his published works, we have a number of letters sent by Ruskin to various correspondents. Some of the earliest are from 1858 in which he writes to a Mr Miller on the terms of acting as tutor to Miller and his advice on what to draw while in Switzerland:

“instead of drawing mountains [I] would draw architecture – namely any parts of the towns either of Lucerne – Schaffhausen – Lausanne, or Bellizona, if you happen to go there”.

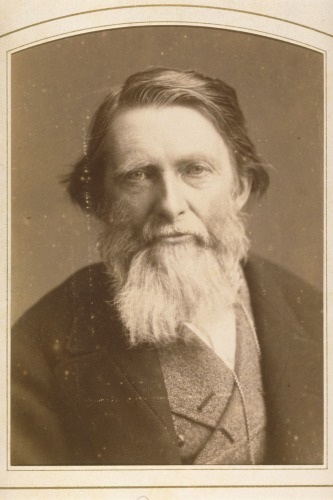

For this blog, we wish to focus on Ruskin’s involvement in the scientific world, notably his connections to St Andrews through his friendship with Principal James David Forbes (1809-1868).

Professor James David Forbes, a native of Edinburgh, was originally destined to be a lawyer but studied science in secret and started an anonymous scientific correspondence with Sir David Brewster in 1826. His love of science prevailed as he abandoned law and went on to hold the Chair of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh from 1833 until 1859, at which point he moved to St Andrews to succeed David Brewster as Principal of the United College.

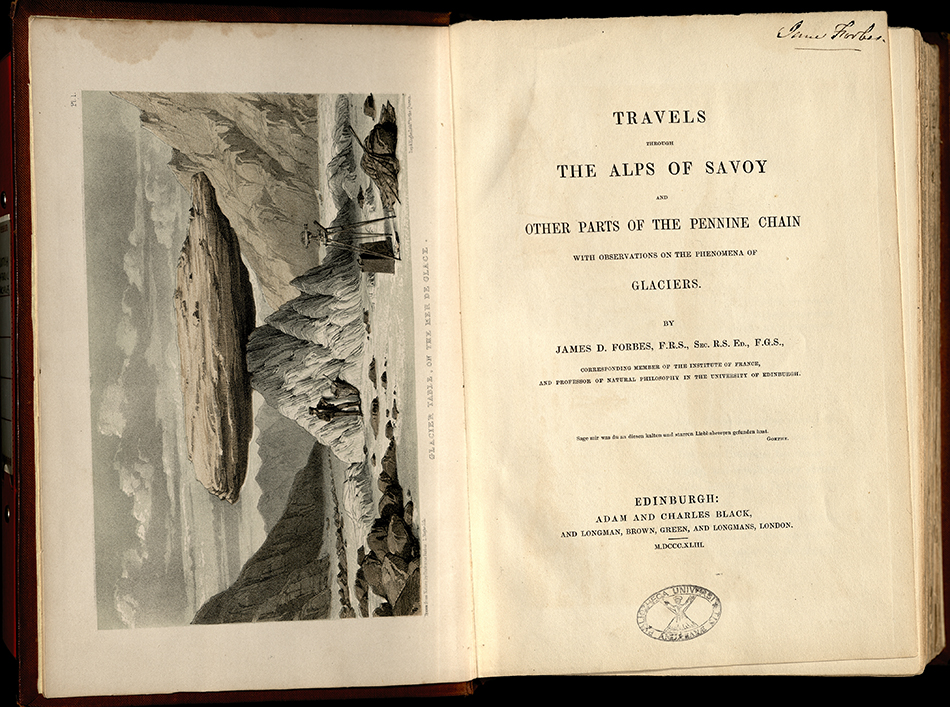

From the first family trip to Naples in 1826 to see Vesuvius, Forbes travelled throughout Europe over the course of his life. He documented his trips to the Alps with the publication of Travels through the Alps of Savoy and other parts of the Pennine chain: with observations on the phenomena of glaciers in 1843. It was on one of Forbes’ trips to the Alps that he and Ruskin would meet.

Ruskin began travelling in the Continent in the 1830s as part of his education but, according to Collingwood’s biography, it was in 1844 that the two men first met at Simplon, Switzerland. In Ruskin’s Deucalion (1879) he recalls his first meeting with Forbes in which, upon Ruskin sharing his drawings, Forbes turned to him “as to a recognized fellow-workman – though yet young, no less faithful than himself.”

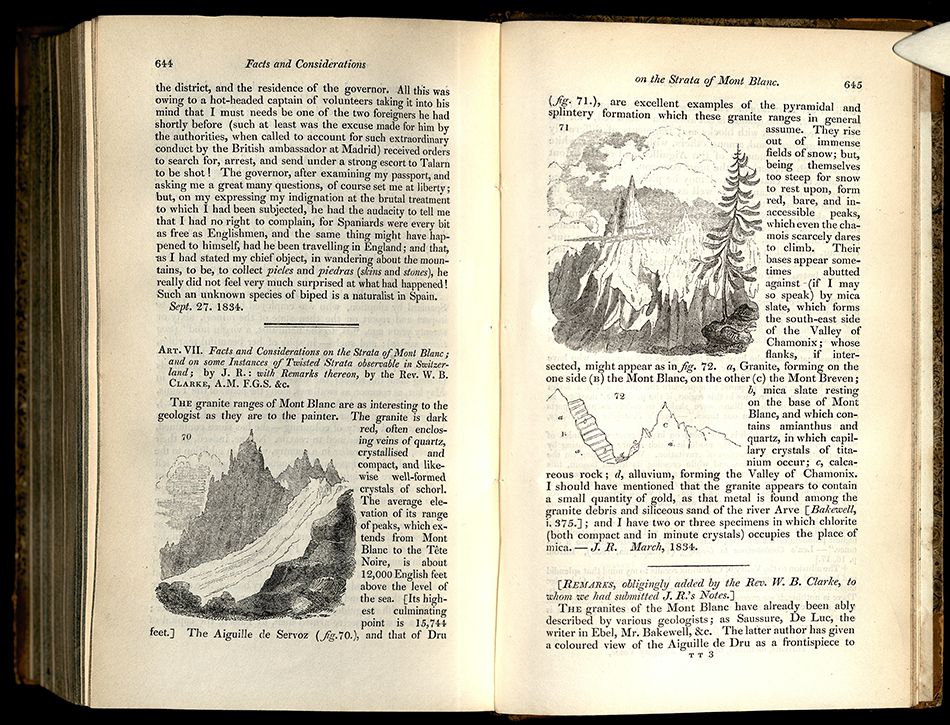

Ruskin’s interest in geology began in childhood as he makes clear in Deucalion. Before beginning his studies at Christ Church, Oxford in 1836 he had already published articles on geology, including a contribution to Loudon’s Magazine of Natural History in December 1834 titled Facts and Considerations on the Strata of Mont Blanc. Ruskin continued to write about the Alps. In fact, his book IV of Modern Painters, published in 1856, was titled On Mountain Beauty. His contribution to observations on mountain landscapes was acknowledged by the Alpine Club (the world’s first mountaineering club) with an Honorary membership in 1869.[1]

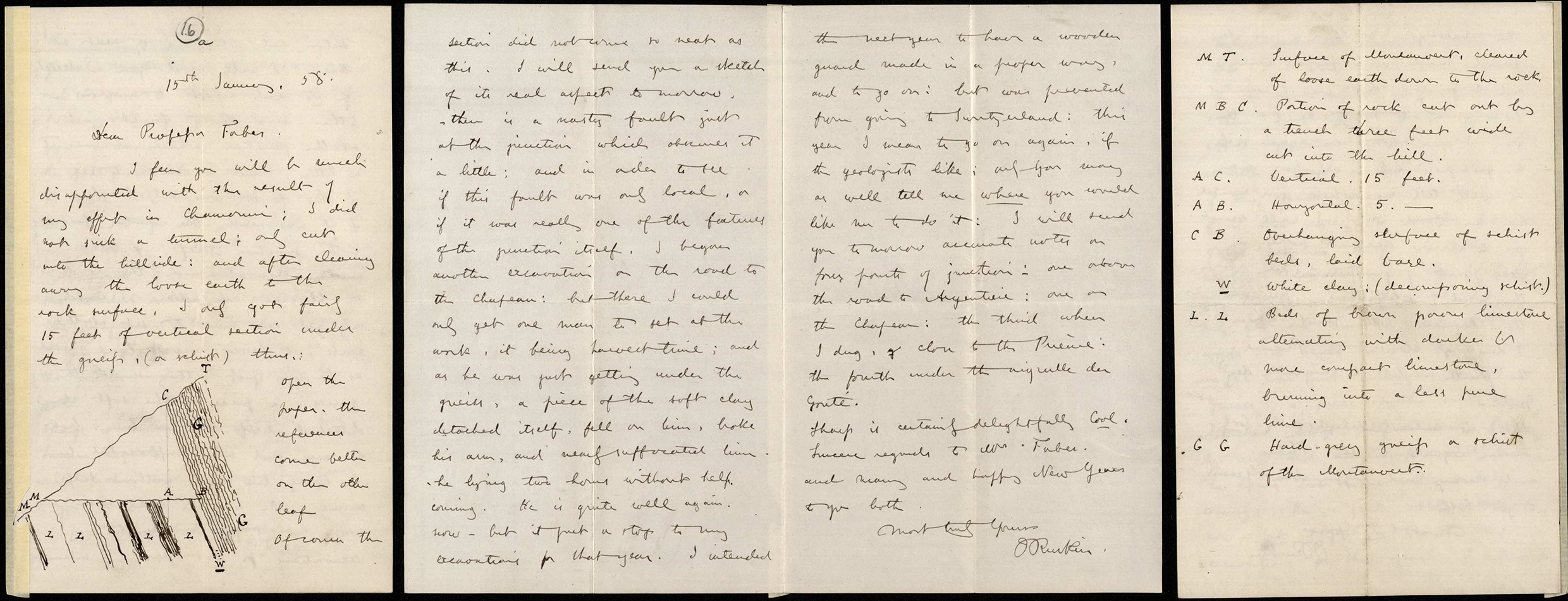

The surviving letters in St Andrews from Ruskin to Forbes focus on their shared interest in landscape and geology. In the earliest letters, Ruskin discusses such topics as the Scottish landscape around Pitlochry and Crieff and his own field observations on the geology of the Chamonix area of France, complete with diagrams.

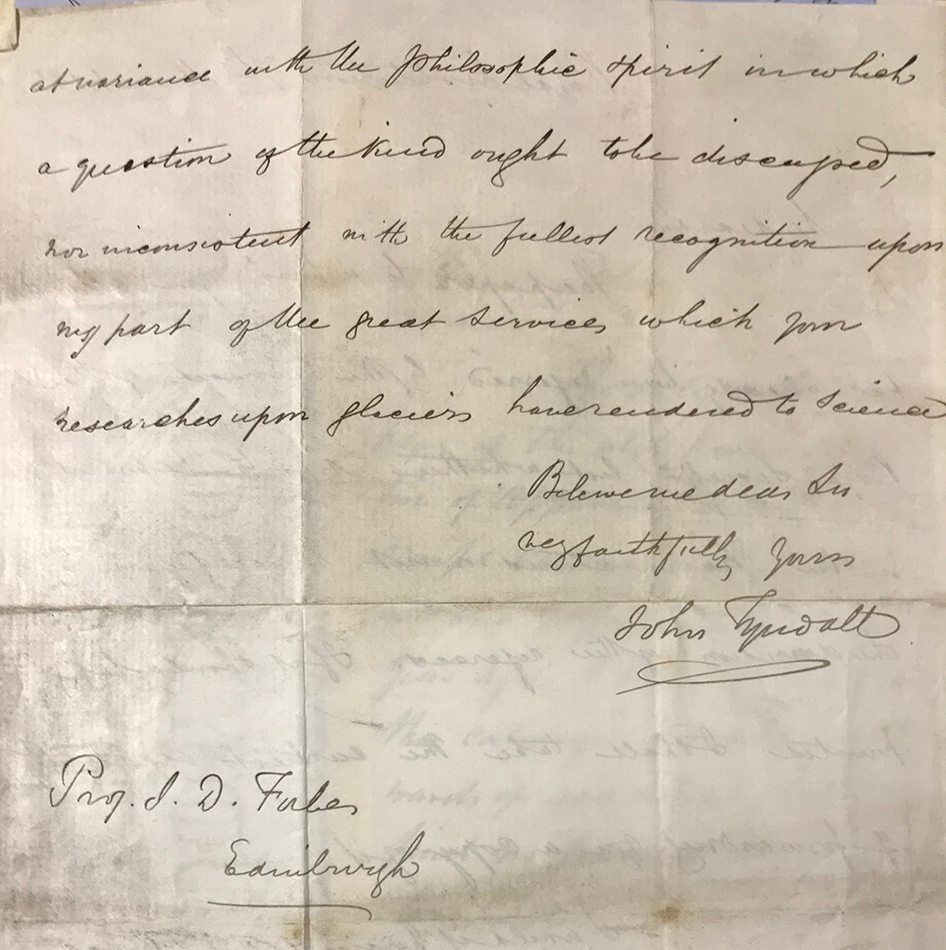

The relationship between Forbes and Ruskin is most well known in connection to the debate over glacier motion, or ‘the Great Glacier Controversy’. In his Travels through the Alps of Savoy (1843), Forbes described the motion of glaciers as that of a viscous fluid. John Tyndall, Professor of Natural Philosophy at the Royal Institution delivered a paper to the Royal Society in 1857 in which he proposed his theory that glacier motion was a combination of fracture and regelation (a phenomenon discovered by Michael Faraday). Forbes received many letters from eminent scientists of the day, such as Charles Lyell, William Whewell, Bernhard Studer and William Thomson, discussing Tyndall’s paper on glaciers and Forbes himself may not have seen Tyndall’s proposal as contrary to his own. In fact, Forbes was in correspondence with Tyndall requesting a copy of his paper to which Tyndall obliged and in an earlier letter to Forbes Tyndall stated his hopes that he will not find it “inconsistent with the fullest recognition upon my part of the great services which your researches upon glaciers have rendered to science”.

However, the debate took a more personal turn in 1859 when Tyndall’s friend and supporter Thomas H Huxley sent a letter to the Royal Society claiming that Forbes had plagiarised his theories from the French glaciologist Louis Rendu. Forbes had already been involved in a dispute over credit with Louis Agassiz after the publication of Forbes’ work in the 1840s. In his book Glaciers of the Alps (1860) Tyndall, in addition to questioning the validity of Forbes’ theory, repeated the claims of plagiarism against Forbes. The debate would continue for many years in print even after Forbes’ death in 1868. For some, this debate over Forbes’ theory may be part of a much wider discussion between those in favour of scientific naturalism, such as Tyndall, and those who argued for the role of religion in experimental science.[2]

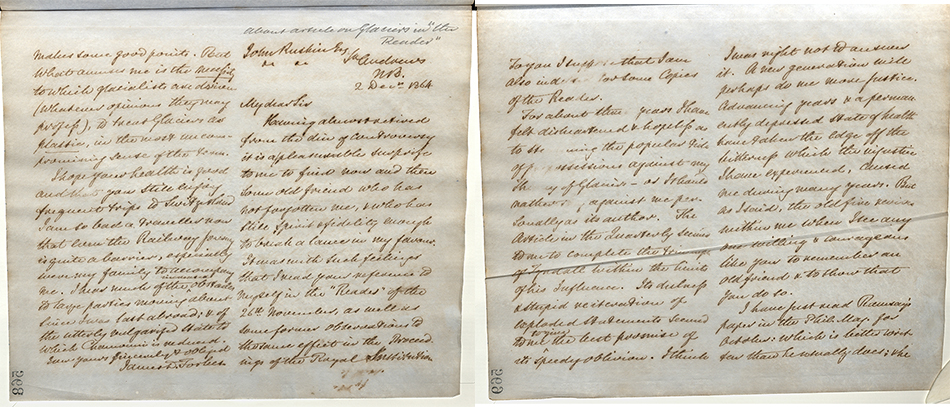

In this debate Ruskin firmly took the side of Forbes and in a letter from Forbes to Ruskin in 1864 we see the value of such support:

Having almost retired from the din of controversy, it is pleasurable surprise to me to find now and then some old friend who has not forgotten me, and who has still spirit and fidelity enough to break a lance in my favour. …

For about three years I have felt disheartened and hopeless as to stemming the popular tide of prepossessions against my “Theory of Glaciers,” or, I should rather say, against me personally as its author…

Advancing years and a permanently depressed state of health have taken the edge of the bitterness which the injustice I have experienced caused me during years. But, as I said, the old fire revives within me when I see any one willing and courageous, like you, to remember an old friend, and to show that you do so.

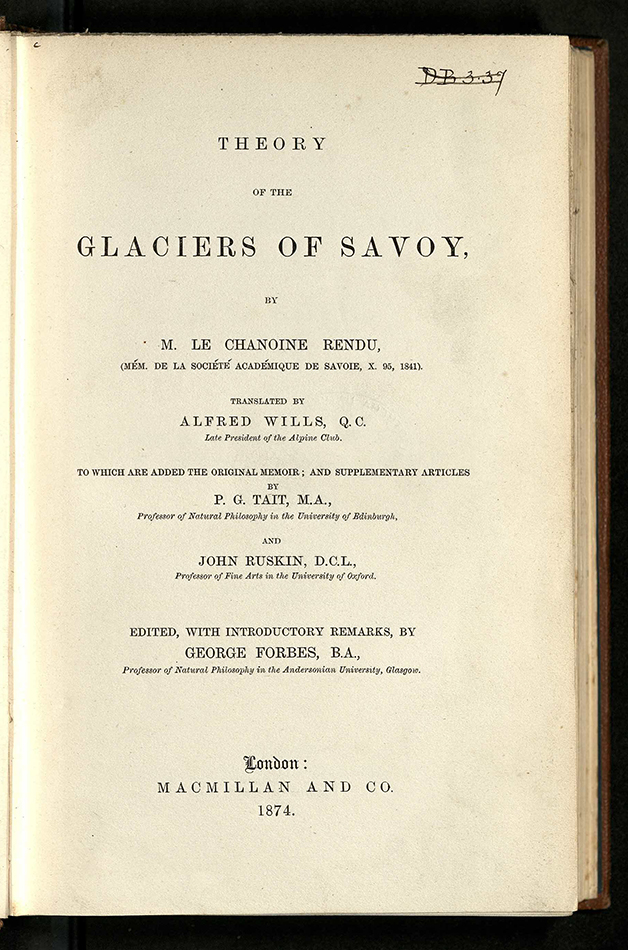

After Forbes’ death, Ruskin continued his correspondence with his son George Forbes. Their correspondence concerned the 1874 publication of a new edition and translation of the work of Rendu, a work undertaken by Forbes, as explained in the introductory remarks, in response to the publication of Tyndall’s Forms of Water (1872) and Principal Forbes and his biographers (1873). Additional commentary was included from PG Tait, who had succeeded Forbes as Professor of Natural Philosophy at Edinburgh, George Forbes himself and Ruskin.

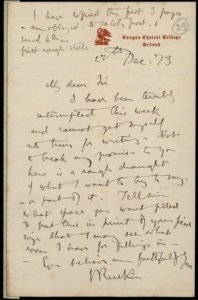

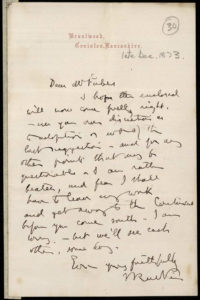

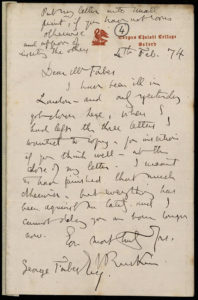

Here are some of the letters from John Ruskin to George Forbes from 1873 to 1874 (msdep7/IncomingLetters):

- Letter from John Ruskin to George Forbes, 1873

- Letter from John Ruskin to George Forbes, 1873

- Letter from John Ruskin to George Forbes, 1873

- Letter from John Ruskin to George Forbes, 1874

- Letter from John Ruskin to George Forbes, 1874

In this new translation of Rendu’s Theory of the Glaciers of Savoy, translated by Alfred Wills, the commentary provided by Ruskin included the published form of the 1864 letter from Forbes (as shown above), along with a letter from Robert B Watson to Ruskin on his memories of Forbes as a teacher. The text also included extracts from letter 34 in Ruskin’s Fors Clavigera (1870s), his published series of letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain. This letter included his reaction to Tyndall’s Forms of Water and the claims against Forbes.

The debate between Forbes and Tyndall is much more complex that can be fully discussed here. The letters from Ruskin in the Forbes collection however reveal a meaningful friendship which Forbes valued.

Ruskin, having caught influenza, died on the 20th January 1900. The breadth of his interests has become the subject of many different disciplines of research, not least his involvement in the history of natural sciences.

Sarah Rodriguez

Principal Archives Assistant

[1] E. Sdegno (2015). The Alps. In F. O’Gorman (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to John Ruskin (Cambridge Companions to Literature, pp. 32-48). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] Nanna Katrine Lüders Kaalund (2017). A frosty disagreement: John Tyndall, James David Forbes, and the early formation of the X-Club, Annals of Science, 74:4, 282-298