International Women’s Day 2019: The first women in the Library

The theme for International Women’s Day (IWD) 2019 is ‘Balance for better’ with a call to action to help ‘forge a more gender-balanced world.’ Women have been studying at St Andrews for 127 years having been first admitted to the University as students in 1892 – though the University’s Ladies Literate in Arts (LLA) scheme began earlier in 1877 as a distance learning qualification for women. Although the history of women at St Andrews is a fraction of the University’s 600-year history, more recent statistics suggest the sex/gender balance in the student population (2017) is now in favour of female students (58.4%), compared to male (41.6%).

Tracing the history of women employed by the University is more difficult. We cannot say for sure who the first woman to be employed by the University was, although the 16th century statutes of St Leonard’s College include the rule that no woman was to be allowed entrance to the college except for the laundress, and only if she was over 50 years of age! The first woman to be appointed as a University lecturer, as highlighted in previous IWD’s posts, was Alice Marion Umpherston (1863-1957) – employed to teach Physiology to women students in 1897.

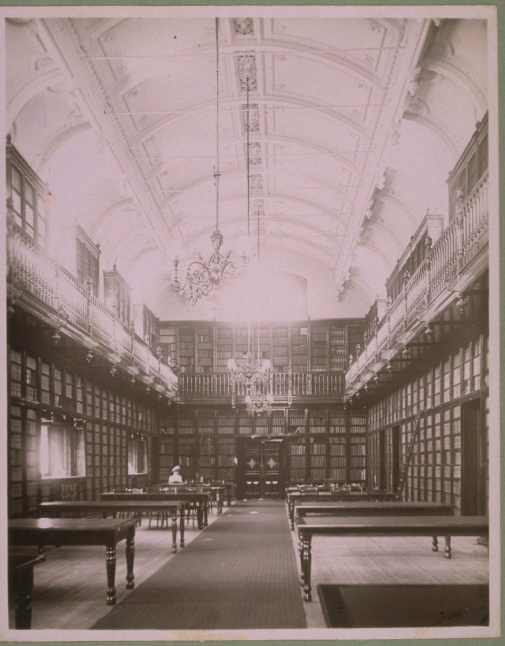

In honour of International Women’s Day 2019, we thought we would stay closer to home and take a look at the history of women in the University Library, in particular the earliest women who served as members of library staff.

Research by Dr Karen MacAulay tells us that women have been borrowing from the Library since the early 1800s. The Library’s borrowing registers reveal Professors taking out books on behalf of women, possibly their friends and family members. The later student borrowing registers include female students borrowing books from 1892 when the University was first opened up to them. Miss Elizabeth Lambert produced a handwritten catalogue of the music held by the Library in the 1820s. However, the history of women employed more formally by the Library starts around the same time as female students were admitted, in the late 1890s.[1]

While we cannot say definitely who the first woman to be employed in the Library was, the first woman to be listed in the University Calendar as a member of Library staff is Mary Davidson Cornfoot (1878-1953), Assistant Librarian. The minutes of Court for the 22nd September 1898 reported that Mary Davidson Cornfoot was engaged as a ‘female junior assistant’ at a salary of £30 a year to allow the Library to increase its opening hours from 19 to 32 and for progress to be made in compiling and publishing the Library catalogues. While we know little about Mary’s personal life, beyond her being the eldest daughter of Captain Cornfoot of 7 Melbourne Place, St Andrews, her career in the Library was to last 47 years! The Library Committee minutes (6 February 1946) record its appreciation for her service, describing how she will be remembered by generations of readers, both students and teaching staff alike and how she had generously delayed her retirement to the end of the war to help during the staff shortage. Her retirement was also reported in the St Andrews Citizen, which commented that her service, second only to Miss Best at Aberdeen University Library, was “longer that any other lady in University Libraries in Britain.’ Her obituary in 1953 observed that she had a strong interest in politics and also had served as Vice-President of the Women’s Committee of the St Andrews branch of the Unionist and Liberal Association.

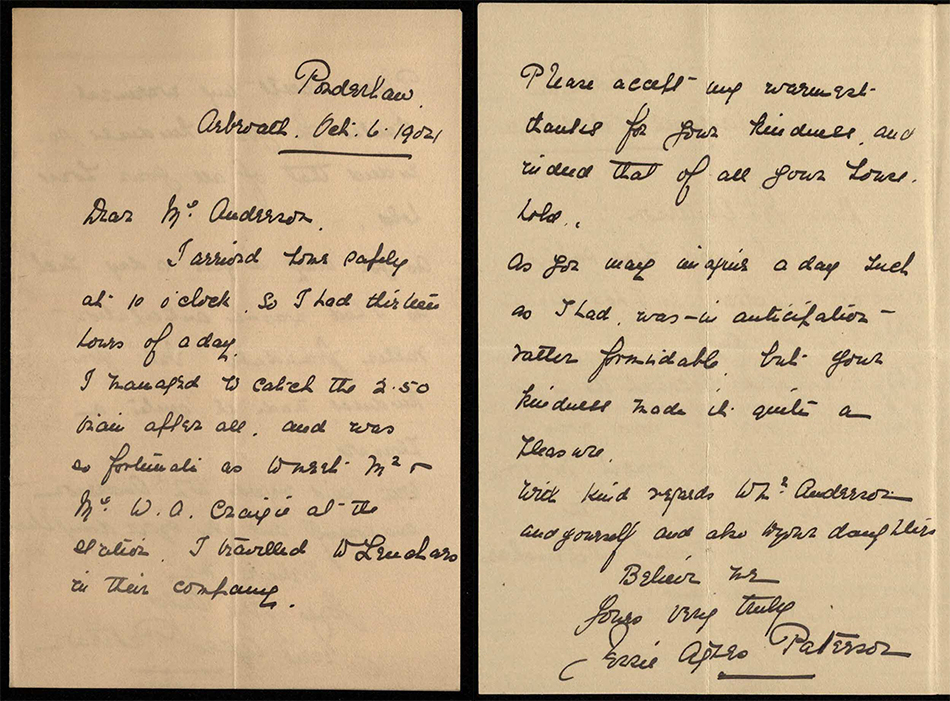

Jessie [Jane] Agnes Paterson (1876-1941) was appointed as Library Assistant on the 24th of October 1904 at a salary of £70 per annum. Jessie attended Arbroath High School and served as a Library Assistant in the new Public Library in Arbroath before taking up her post at St Andrews. Jessie, like her sister Edith, had completed the LLA (Ladies Literate in Arts) and was also a student in United College for the academic session 1893-1894, studying French. Within the Librarian’s correspondence there are a few letters from Jessie regarding her interview for the post, including a letter of thanks to the Librarian James Maitland Anderson for the kindness shown to her on her visit to St Andrews and her fortuitous encounter with Mr W. A. Craigie (lexicographer and philologist who studied and worked at St Andrews) and his wife, on the train journey home to Arbroath.

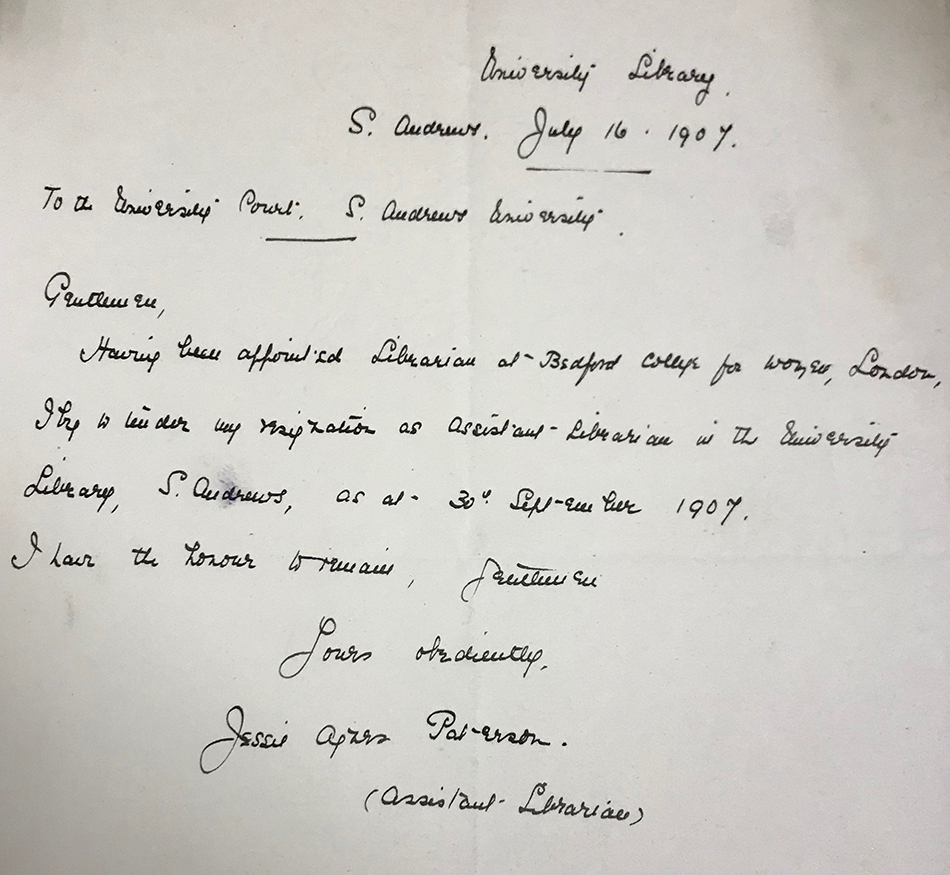

Jessie left the University in September 1907 to take up a Librarianship post at Bedford College for Women at the University of London, where she would remain for over 30 years until her death. Sadly, Jessie was killed during an air raid in April 1941. A memorial service was held for her in King’s College Chapel, Cambridge (where Bedford College had evacuated to during the war) in addition to a family service back in Arbroath. A reporter in the Arbroath Herald said of her that she would be remembered as a “true Scots woman, finely cultured student, and a great librarian.”

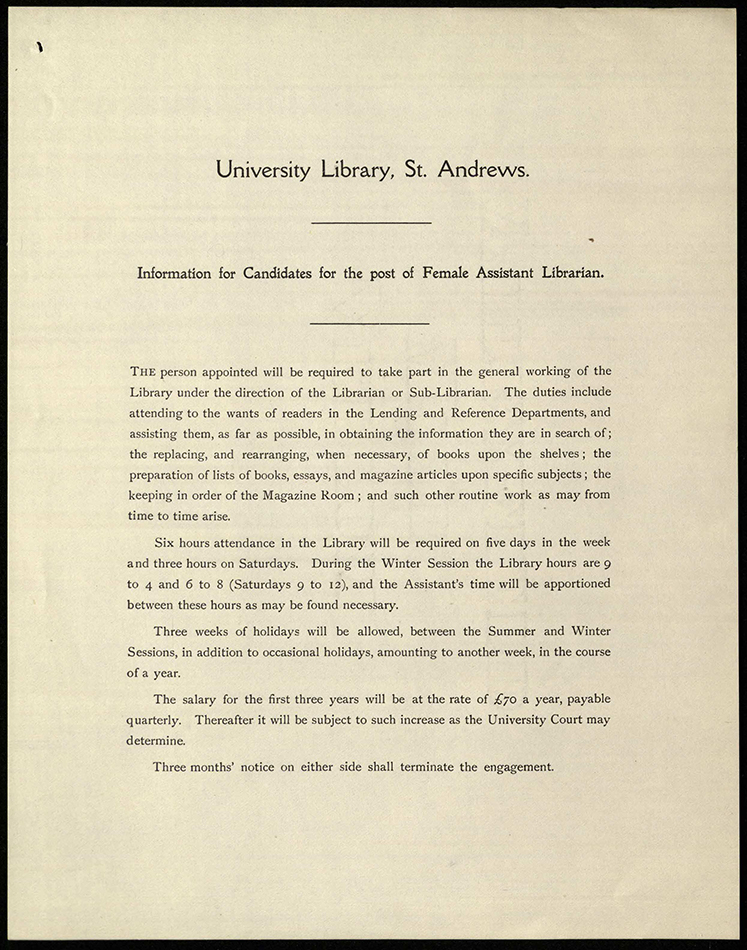

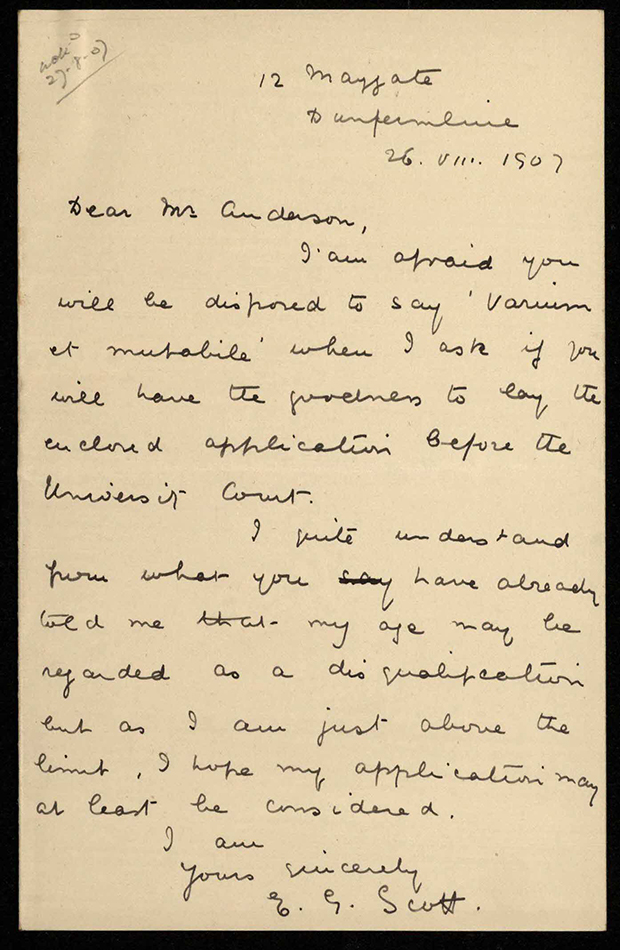

The vacant post left by Jessie in 1907 was advertised by Maitland Anderson in The Scotsman. In his notes we find that he received over 100 letters of interest in the post of ‘Female Assistant Librarian’ (a job description very much of its time!) The job advertisement specified that the candidates must have a University education, or equivalent and from his notes we know that around 15 graduates and 10 LLAs applied for the post. The post was offered to a St Andrews graduate Miss Ellen Gillespie Scott (1876-1961) from Dunfermline. However, we see in the letters sent by Scott to Maitland Anderson that she nearly didn’t apply for the post, being over the age qualification limit of 30!

Scott was a student in United College from 1896 to 1902, gaining first class honours in English. After graduating with an MA, she held the Berry Scholarship in English in 1902 and, according the testimonial from Alexander Lawson, Berry Professor of English Literature, “did excellent University Tutorial work during the Winter Session 1902-3” so much so that her scholarship was renewed for the Winter Session of 1903-4. As part of her scholarship she was involved with teaching in the English Department, including Old English of which Professor Lawson said, “she has competent knowledge.” Dr Mackinnon of the History Department said in his 1901 testimonial for Scott that

“Personally I regard her as a friend as well as an old student, and heartily hope that she will realise in her future career the high expectations I have formed in regard for her.”

Despite the ill health referenced in her own letters as the cause of having to give up teaching before joining the Library, Scott worked as Assistant Librarian for the library for 35 years, retiring in July 1942.

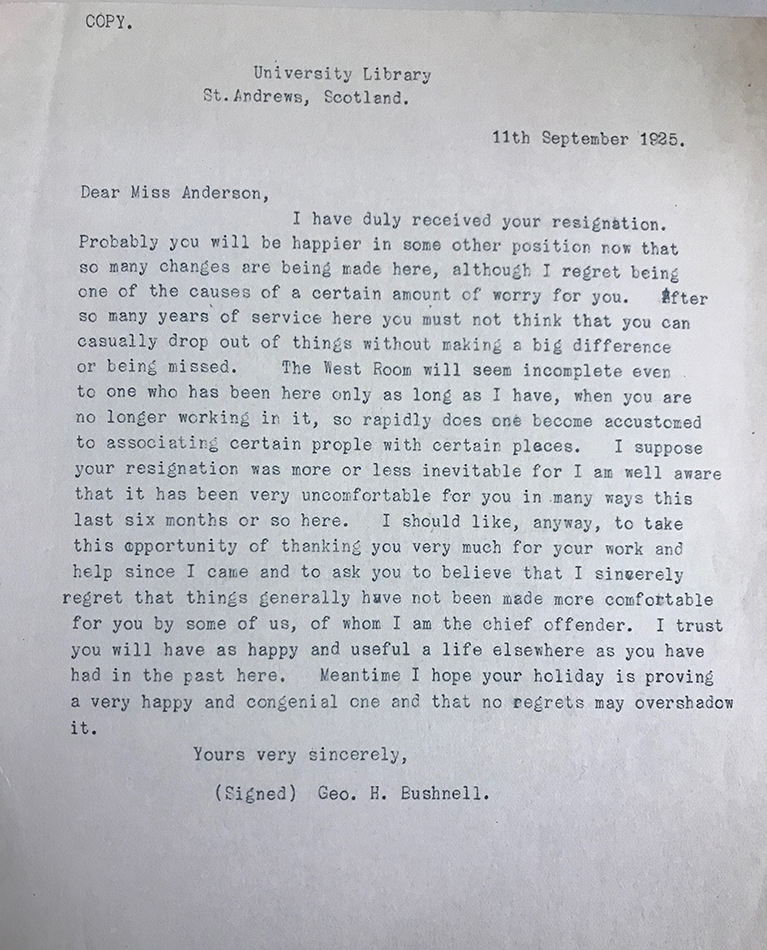

The Library’s Annual Reports record the appointment of a temporary cataloguer and indexer in 1902. Miss Helen Maitland Anderson (1884-1968), joined the staff with the approval of court for 1st January to 30th September 1902. As Helen was the youngest daughter of the Librarian James Maitland Anderson (her elder sister Elizabeth was a student at the University from 1899-1904), we could presume that this was a form of early work experience that her father offered her in the Library. Yet, the Library’s Annual Reports reveal that she continued to work in the Library for many years until September 1925, resigning not long after her father retired from the Library. Unfortunately, little is known about Helen personally or her time with the Library, with the exception of a copy letter from her father’s successor Bushnell in response to her resignation. The Misses Maitland Andersons though are mentioned frequently in the St Andrews Citizen as being involved in various activities in the town.

In his own notes, George Herbert Bushnell suggested that he was appointed as University Librarian in 1925 to reorganise and re-catalogue the Library. He introduced Library of Congress classification for the first time and implemented much needed renovations.

From 1720 the position of Librarian had been combined with the post of University Secretary and until 1892 the post-holder also undertook the duties of Quaestor. Bushnell’s predecessor, Maitland Anderson had also been University Registrar and Keeper of Muniments, as well as continuing his work as an eminent historian. It is perhaps no wonder that work in the Library had not progressed as quickly as perhaps needed given Anderson’s responsibilities.

At the same time as Helen Maitland Anderson resigned in 1925, Ellen Scott submitted a letter of complaint to Court regarding the re-arrangement of staff duties in 1925. While the exact nature of the complaint is unknown it perhaps concerned the labour required to implement the changes Bushnell had brought in. A memorandum in the Library Committee minutes dated January 1925 recommends taking on more staff and reveals interesting attitudes of the time to the gender roles in the workplace:

“The present staff is not large enough to carry out these suggestions or any other reformations as expeditiously as may be thought desirable. The provision of one male assistant more or less trained and qualified and a typist would enable the whole of the suggestions […] to be put into practice.

[…]

“During the period of reorganisation a certain amount of labour of a nature unsuited to female assistants will be unavoidable, so that additional male assistance is particularly desirable.”

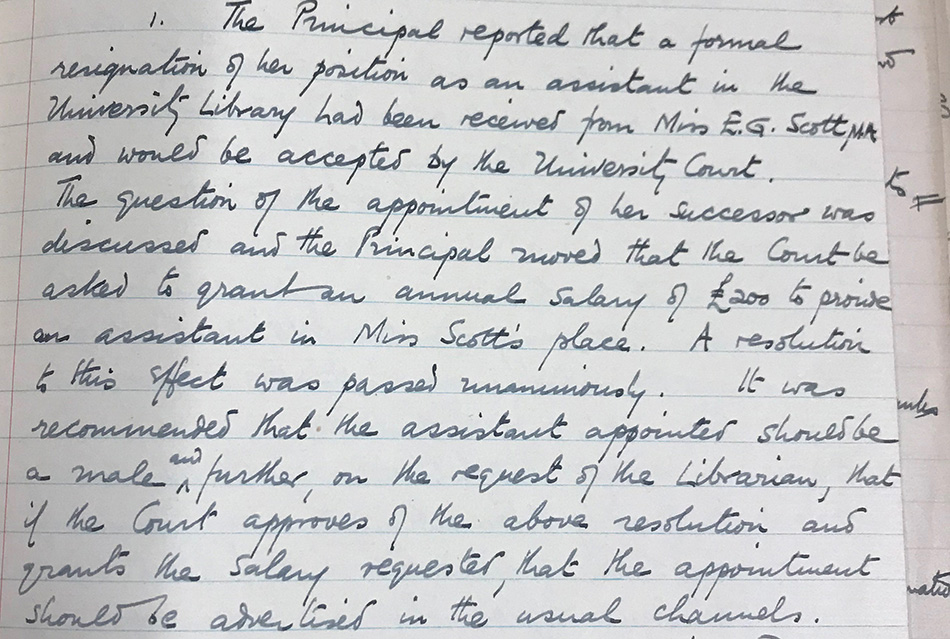

It is not clear what duties were unsuitable for female assistants (most likely the physical work of moving books) but we find again the issue is raised when Ellen Scott resigns in February 1926 and the Library Committee makes the recommendation that the candidate selected as her replacement should be male (Ellen later withdrew her resignation and remained on staff until 1942).

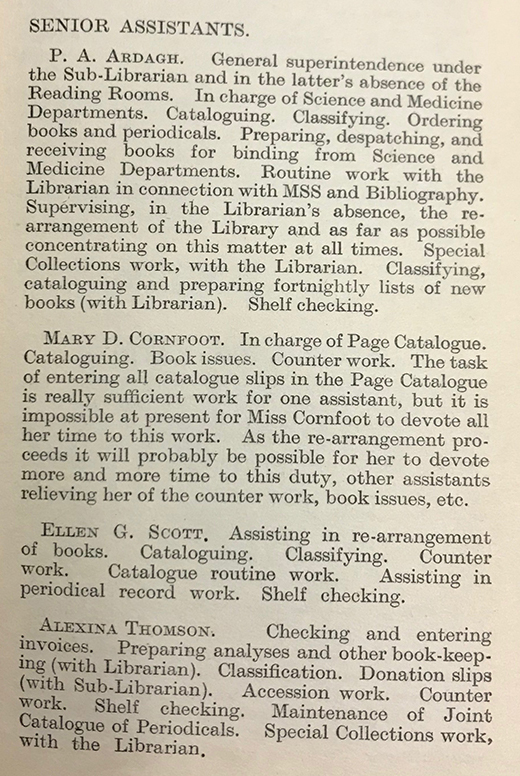

To get a sense of the work carried out by library staff around the time of these women we can look at the Library Manual (1926) published by Bushnell. We find that all assistants were expected to study Latin, Greek, French, German and English languages and literatures as well as Library Administration. There were four Senior Assistants in 1926, including Mary D. Cornfoot and Ellen G. Scott. Their duties involved cataloguing, classifying and working on the counter. The duties of junior assistants George Fairbairn and Andrew Thomson, who according to the Library’s Annual Reports had been employed in 1925 as ‘boy assistants’, included moving books, clearing tables, shelving and dusting books, working on the counter, filing and assisting the more senior staff with their duties.

***

The Library Annual Reports from the first half of the 20th century reveal that there were other women working in the Library, both as assistants and typists. Little is known about them though beyond the recorded start and finish dates and the rare reference to the library training they received.

Moving on to the present day, the gender balance of Library staff is approximately 69.6% female and 30.4% male. While this statistic may support the common stereotype of Librarians as predominantly female, in the history of this University Library, of the 31 people to hold the post of University Librarian (the most senior member of Library staff), only one has been a woman (in an acting role).[2] Perhaps this is a reflection of the history of the struggle for women to be in positions of management. In saying this though, currently in the Library many of those in senior management, including all four of the Library’s Assistant Directors, are women.

***

To mark International Women’s Day 2019 the University has asked colleagues from across the University to share their thoughts on what ‘balance’ means to them. For more take a look at the University’s stories page: https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/stories/2019/balance-for-better/.

Sarah Rodriguez

Principal Archive Assistant

[1] The terms female and woman/women will be used interchangeably throughout this blog.

[2]Library Keeper or University Librarian:

John Govan (1642-1644), Thomas Lentron (1644-1662), Patrick Walker (1673-1687), Alexander Fairweather (?1687-1696), Thomas Greig (1696-1699), James Henry (1699-1702), John Crie (1702-1718), James Small (1718-1720), James Agnus (1720-1747), Andrew Angus (1720-1748), Laurence Adamson (1748-1768), William Vilant (1768-1788), Charles Wilson (1788-1792), John Cook/James Thomson (1792-1796 Joint Librarians), John Cook (1796-1815), Daniel Robertson (1815-1817), James Hunter (1817-1839), James McBean (1839-1863), Alexander Muir (1863-1864), Robert Walker/William Troup (1864-1869 Joint Librarians), Robert Walker (1869-1881), James Maitland Anderson (1881-1925), George Herbert Bushnell (1925-1961), Dugald MacArthur (1961-1976), Alexander Graham Mackenzie (1976-1989), Neil Frances Dumbleton (1990-2003), Louis Lee (2003-2004), Christine Gascoigne, Acting Librarian (2004-2005), Jon Purcell (2005-2009), Jeremy Upton, Acting Librarian (2009-2011), John MacColl (2011-present)

Reblogged this on Claimed From Stationers' Hall and commented: How lovely to see Miss Lambert included there in this blog about St Andrews University Library's women staff! (even if Miss L. wasn't actually an employee!)

Sorry to see that I am still the only female University librarian

Dear Sir/Madam, RE - New information concerning sepia group photo (Group-1893-2a) at the top of your page. My research concerning University of St Andrews academic (Classics) the Rev. Professor Lewis Campbell indicates that he delivered the Gifford Lectures (on a Theology-related topic) at the University of St Andrews a number of occasions throughout 1894-96 when the photo was taken. Professor Campbell was at this time chairman of the council of the adjacent (predominately senior) girls school - St Leonards - which he had co-founded. He was a very keen advocate for tertiary education for women. The photo clearly has a number of younger students who are wearing special school sashes. These girls would be St Leonard's School "junior" students, of which there were a few at this time. Photographed amongst the external LLA diploma students and the handful of enrolled degree students (who had signed the matriculation roll at St Andrews) are older schoolgirls (with or without mortar boards) who would have enjoyed Professor Campbell's Theology lectures. These schoolgirls had been encouraged by their principal at this time - Miss (later Dame) Frances Dove - and other staff to (quietly!) attend certain lectures at the university from the 1880s. The Gifford Lectures were described at the time as being open to a "mixed" audience, including those from the university community who had both (preferably) matriculated and, of course, paid the attendance fee. I note with humour that the older men and university academics are all at the back of the photo - a polite distance away from the ladies. The male undergraduates, perhaps being keen to leave as soon as possible, are notably absent from the photo! I hope this information is of interest to you. Mr Michael Reed Ilim College Melbourne Australia