Collage in the Collections

Visiting Scholar Dr Freya Gowrley reflects on her recent stay in St Andrews.

During my three-week visiting scholarship at the Library’s Special Collections this summer, I conducted work as part of my research project Collage before Modernism. This aims to write a new history of collage by focusing on its manifestations in Britain, North America, and across the British Empire from the beginning of the eighteenth century until its so-called ‘invention’ by the artists Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in France in 1912. In so doing the project seeks to complicate existing histories of collage, such as those proposed by Christine Poggi in her book In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage (1992), which figures collage in terms of Modernist innovation. Contrastingly, the project adopts a broad and encompassing definition of collage, considering various kinds of what I’m calling ‘composite cultural production’ made throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Examining everything from textiles, manuscript volumes, and published texts, to furniture, decorative craft practices, and paintings, the project aims to think in new ways about the desire to collate and combine images and objects. In considering this broad variety of collaged forms, the project hopes to demonstrate the vital importance and ubiquity of collage throughout this period. Arguing that collage permeated the very fabric of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century life, it explores how its production and consumption functioned to express the emotions and identities of those who made, owned, and viewed it. At the same time, the project also asks broader questions about the nature of ‘Art’ itself, using the ways in which collage has been defined, discussed, and dismissed to question some of art history’s key ideas, such as ‘genre’, ‘medium’, and ‘period’.

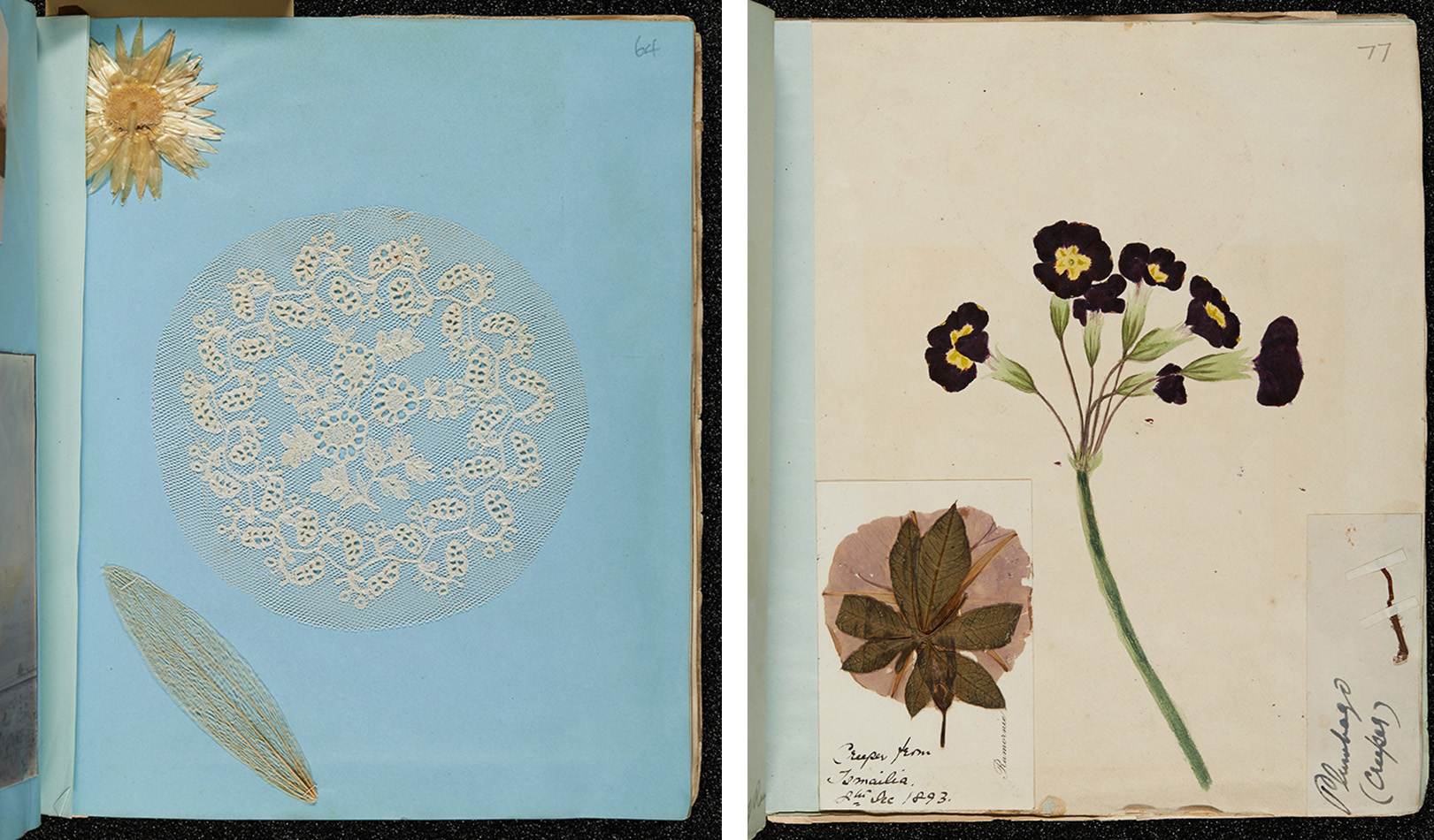

Collage, from the French verb coller, ‘to glue’, is often associated with papier collé, or paper collage. Yet the period between the early eighteenth century and 1912 saw a varied proliferation of collaged forms. With visual, material, and literary manifestations, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries witnessed the production of decoupage, quilts, extra-illustrated or grangerized texts (printed texts embellished with additional images), commonplace books (manuscript volumes containing fragments of excerpted texts), shellwork, scrapbooks, and photomontage, in addition to traditional paper collage. The creation of each of these objects was rooted in the cultural processes through which we often think about collage as being conceptualised and made, particularly those of collection and transformation. From acquisition and selection, to adaptation and reformulation, these objects brought together disparate elements, creating new and highly personal narratives through a complex dialogue of consumption and production.

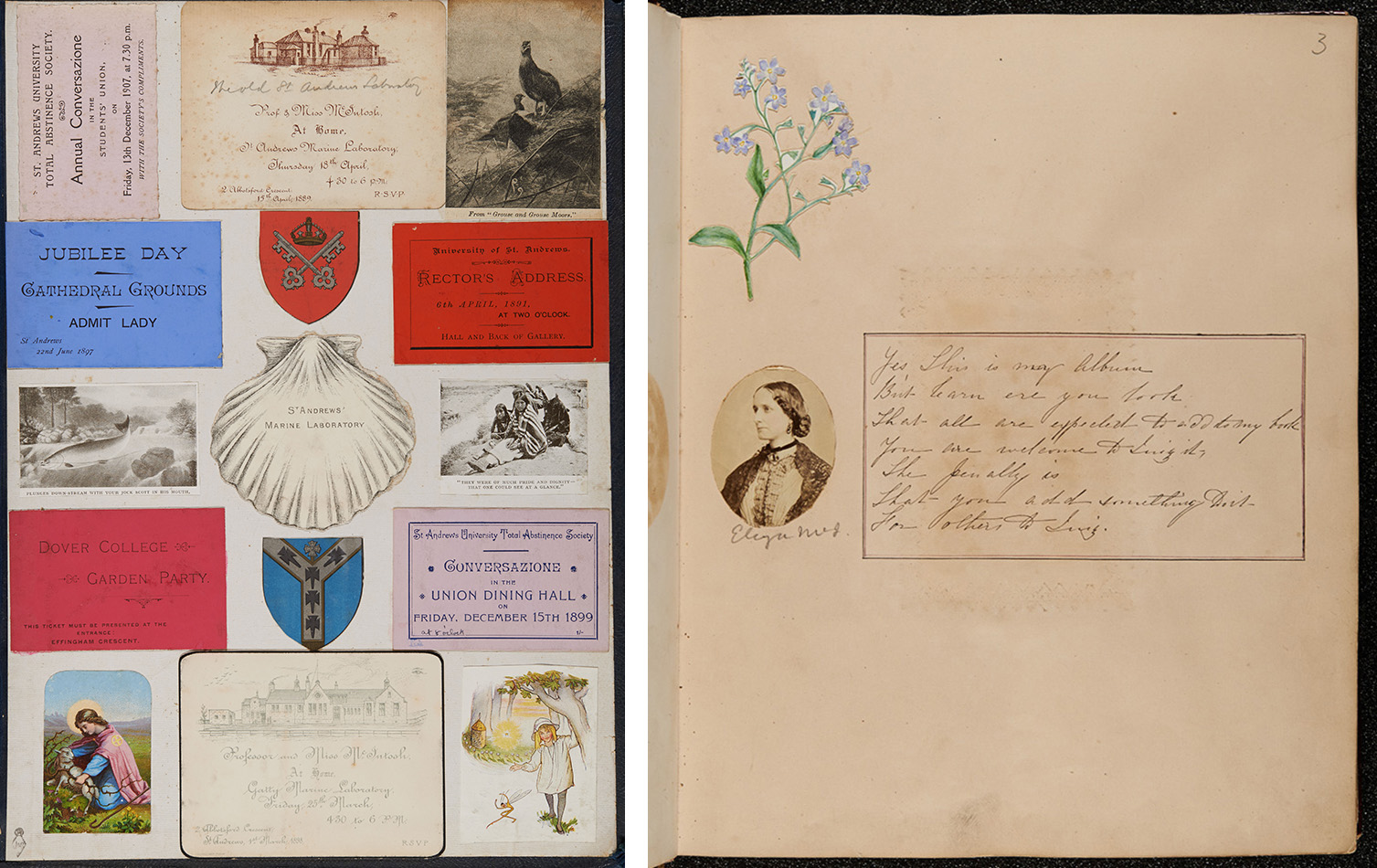

During my time in the Library’s Special Collections my primary focus was on the McIntosh family papers, a uniquely rich and varied collection of visual, material, and textual objects produced by, and relating to, the Scottish marine zoologist William Carmichael McIntosh (1838-1931), his four sisters Agnes, Anne, Eliza, and Roberta (the latter of whom was a noted natural history watercolourist and illustrated several of William’s works), and their mother, also Eliza. Various members of the family created collaged volumes, including scrapbooks, commonplace books, and seaweed albums.

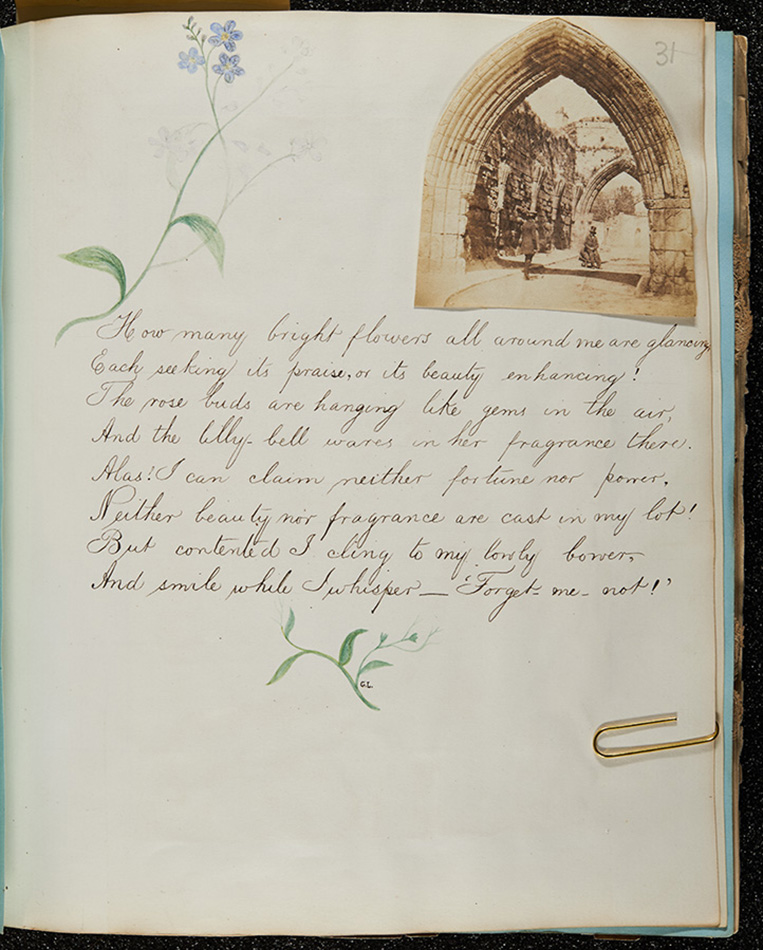

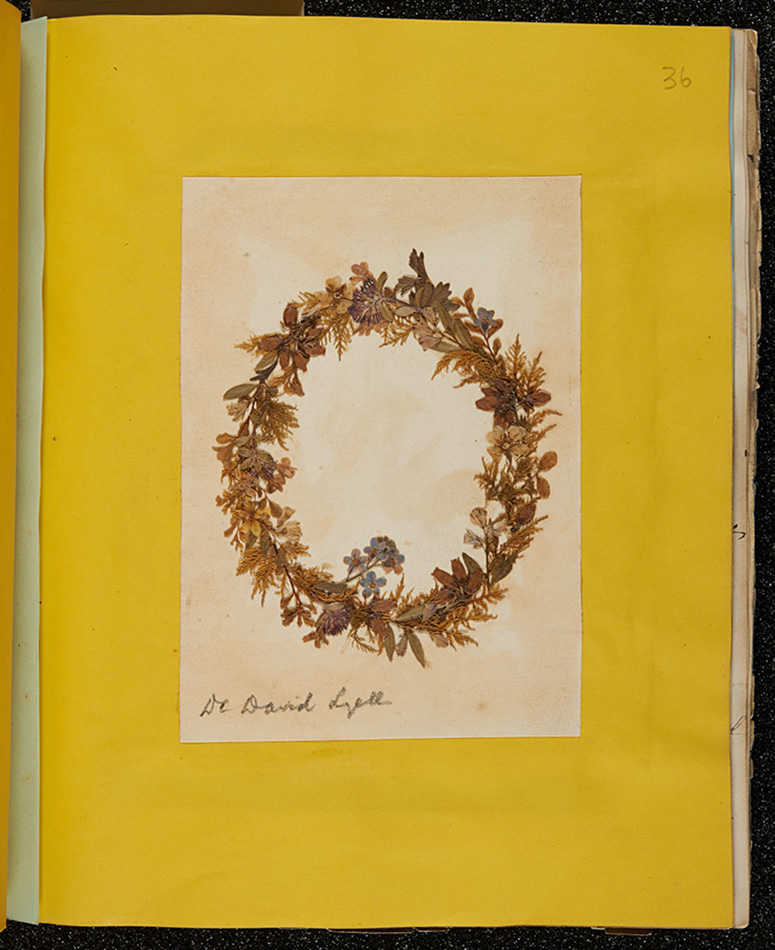

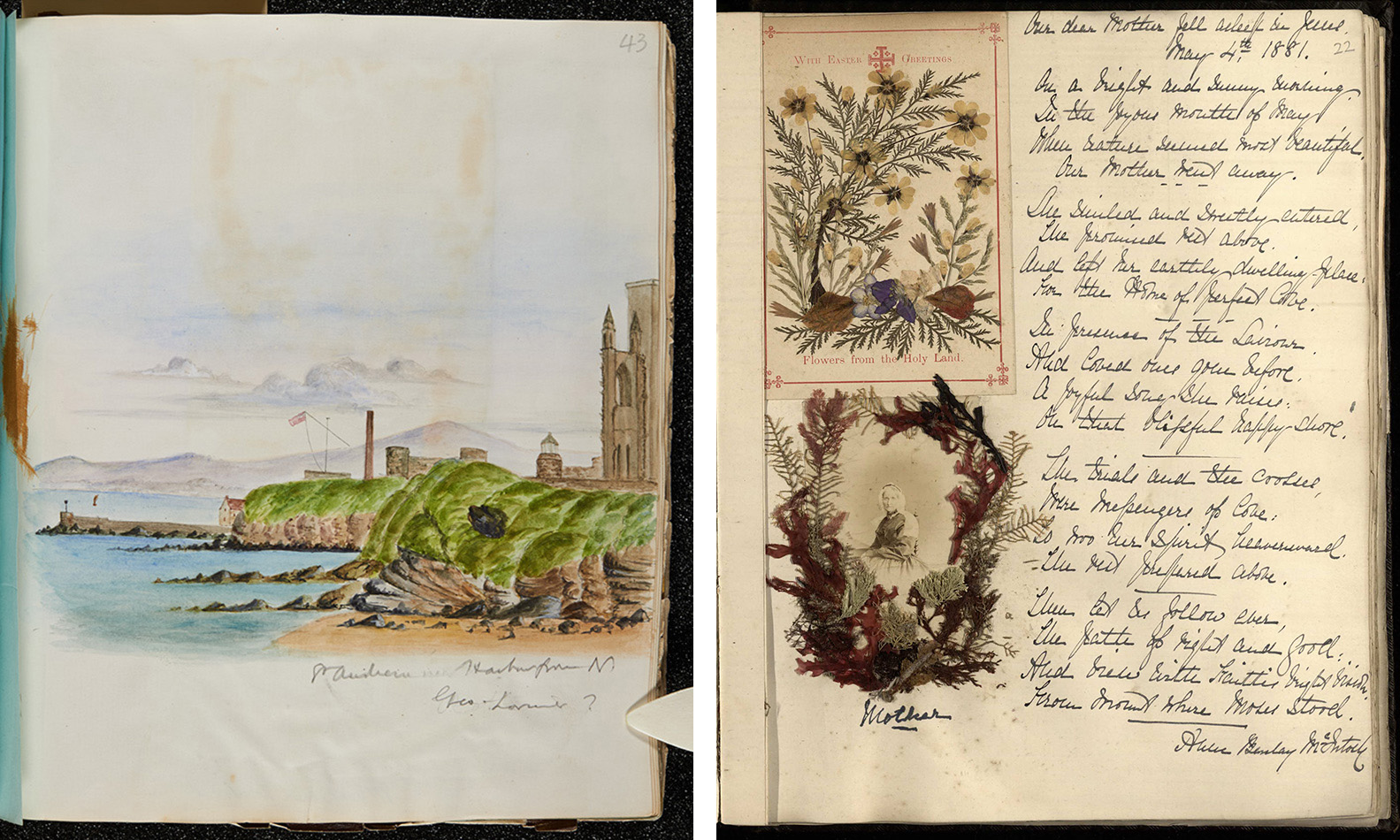

I explored a series of 13 family scrapbooks (ms37102), a significant number of which were made by Agnes and dedicated to William and Roberta’s careers. The collection also boasts a number of family photograph albums compiled by various members of the McIntosh family, as well as Roberta McIntosh’s commonplace book, a complex object including manuscript contributions from various individuals, sketches of family members, collected pressed flowers, albumen prints, and newspaper cuttings. Whilst in Special Collections, I became particularly interested in how these volumes related to a number of interrelated identities, be they national, professional, or maritime. The books often specifically document the family’s broader and explicitly Scottish history, with visual and textual references to ‘Clan McIntosh’ and to Scottish worthies like Scott and Burns. In the albums, this ‘Scottishness’ takes on a notably local character, with many of the volumes dedicated to St Andrews, Fife, and the surrounding area, and evidencing attendance at events in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. With photographs reproducing these sites, and plants from these regions cut and pasted into the volumes, here Scottish identity is grounded within the local natural landscape, one that is also specifically maritime in nature. This interest in the sea of course, also relates to William and Roberta’s professional identities, as natural history writer and illustrator, respectively. At the same time, the volumes also reflect the emotional lives of their makers, employing collage to commemorate losses and grief, and to materialize familial bonds more broadly. In the volumes, for example, seaweed is collected and collaged in order to surround an image of the siblings’ dead mother, thereby uniting family histories with pieces of the landscape in which the family lived and worked.

The proliferation of such collaged volumes within the collection, as well as its extensive surviving correspondence and contextual materials, make the McIntosh Collection an unparalleled source in understanding how such albums, notebooks, and scrapbooks created, sustained, and reflected familial relationships. I look forward to contemplating more thoroughly both the volumes and the question of how their production was bound to the creative, personal, and professional histories of the McIntosh family as I digest the materials I’ve unearthed during the scholarship.

Freya Gowrley

Postdoctoral Fellow in History, University of Derby

Acknowledgements

I am hugely grateful to all the members of the team at Special Collections for sharing their expertise, knowledge, and advice with me. Special thanks must go to Maia Sheridan, who helped me navigate the McIntosh Collection catalogue, and who would often add many exciting and unexpected objects to my order of archival materials each day.

[…] Happy to be sharing my post that I wrote for Echoes from the Vault, the University of St Andrews’ Special Collections blog, following my three-week Visiting Scholarship there. You can get a little taste of how the project fits into my broader work, and of what I was up to whilst I was there, here. […]