A Century of Photographs, Found in Australia

We are pleased to announce that the winner of the James David Forbes Collecting Prize 2019 is Antares Wells, recent graduate in the School of Art History. In this blog, Antares tells us about her winning collection of photography.

I found her photograph in January 2011. She sits on the shore, eyes closed, arms taut, clutching a clump of seafoam. Bathing suit crinkled and damp around her hips, mouth slightly open, she radiates the raw freshness of saltwater on the skin. Against the sheen of the wet sand, the water and foam behind her form lit layers, light and dark by turns. The soft edges of the image appear to liquefy in places. On the back of the photograph is written “1949 2”.

Who she was (or is), where the photograph was taken: these details are missing from the image suffused with light. Methodically searching the hundreds of photographs jumbled together in the box on the floor of the camera shop in Sydney’s Newtown for others printed on the same photographic paper, shot in the same location, or even featuring the same woman yielded nothing. As a found photograph, Seafoam has been loosened from the ties that once bound it to a particular life, family history, and story. An intimate snapshot of a moment in time, it offers up so much while withholding the most basic information. Yet, far from being a deficit, this paucity of detail is partly what gives found photographs their allure. Free-floating, they set off the imagination.

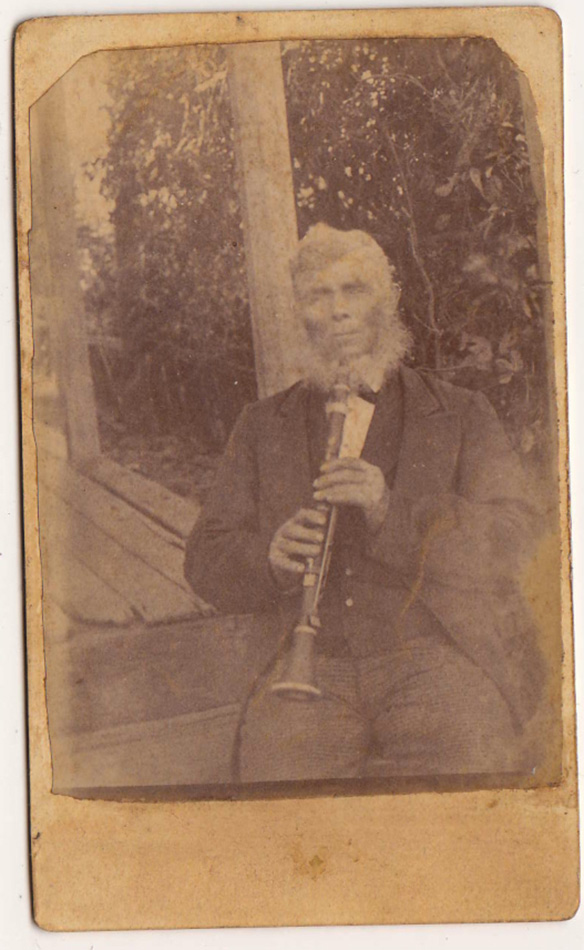

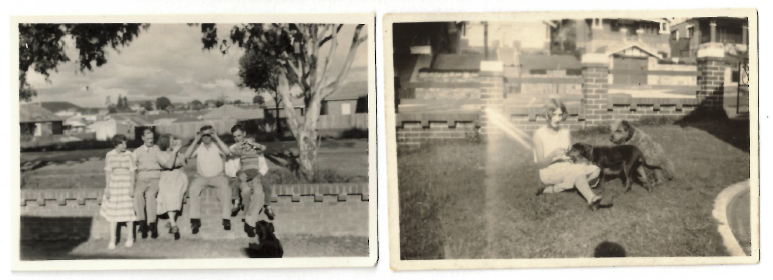

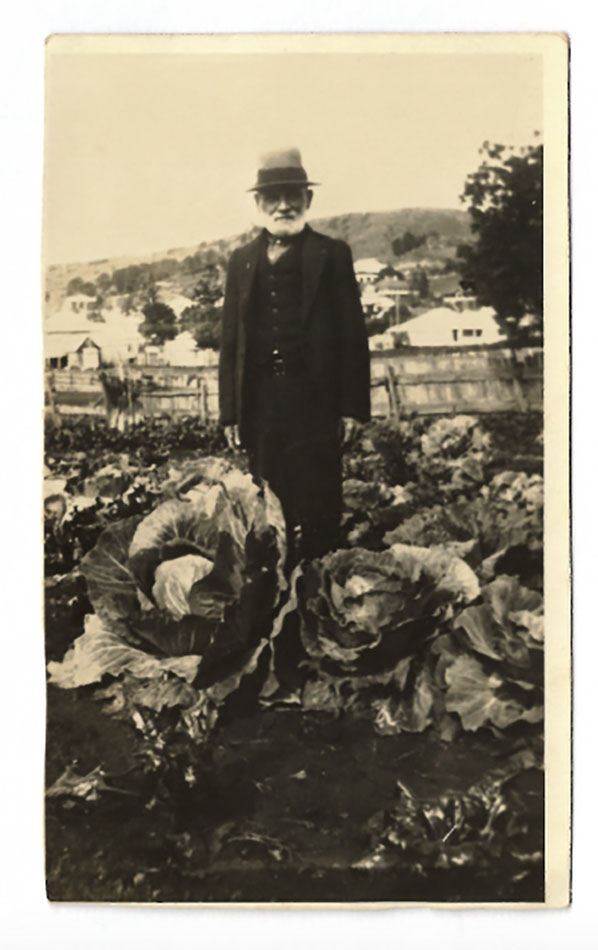

Seafoam is just one of almost 200 images that found their way via flea markets, garage sales, antique stores, and charity shops into my collection of found photographs. With the exception of carte-de-visites and cabinet cards that bear the name and address of the photographic studios in which they were produced, the majority of the photographs in the collection were made by unknown photographers. The collection includes vernacular snapshots, photographic postcards, stereoscopic views, and studio portraits. While dates and names are inscribed on the reverse of some photographs by hand, many are completely unmarked. As a result, I have had to estimate the dates for the majority by paying close attention to photographic technologies and to details in the images themselves. The photographs in the collection span nearly a century, from the late 1870s to the early 1970s, and reflect the ways in which ordinary people engaged with diverse and shifting photographic practices over this period.

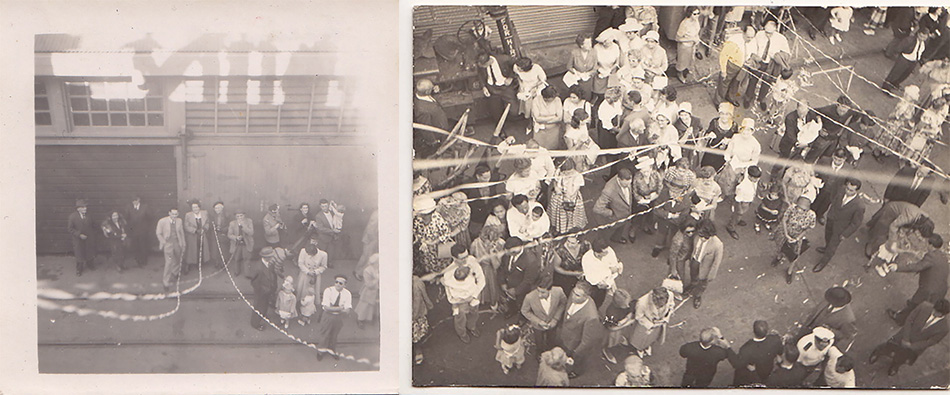

While all photographs in the collection were found in eastern Australia, a number appear to have originated in Thailand, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Nevertheless, the collection has a strong Australian focus, with many photographs touching on elements of Australian culture and society. Australia’s distinctive natural environment features particularly prominently, as does life in the suburbs extending outward from major urban centres. In addition, Australia’s rich migration history is implicit in a number of items, whether in hand-written inscriptions in German, Bulgarian, and Italian on the backs of photographs, or in snapshots taken from the decks of arriving ships, streamers cascading down to the audience gathered on the dock below.

The bulk of the collection comprises portraits of single individuals and group snapshots. Critically, despite its links to both popular photography and Australian social and cultural history, the collection is not intended as representative of a particular historical period, experience, or subject. Rather, I am drawn to images in which subject matter, lighting, and presentation (including idiosyncrasies of the developing and printing process) combine to generate a particular mood. Many of these images could be classed as failures from a printing perspective: they are unintended double exposures, printed on an angle, with light bleeding into them from the sides, yet precisely these elements fuse with the subject to arrest the eye.

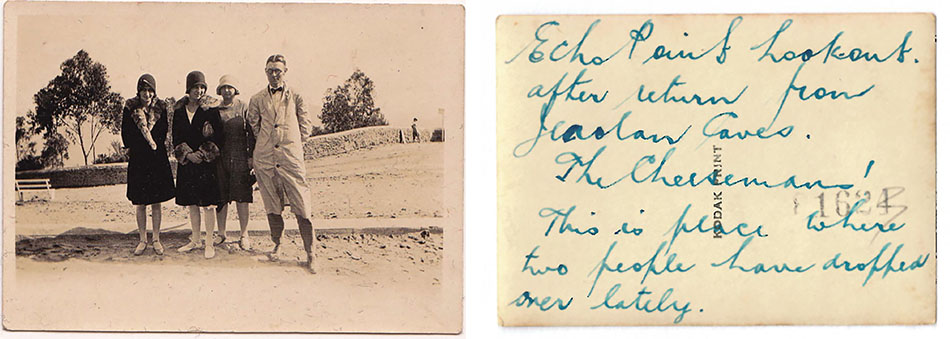

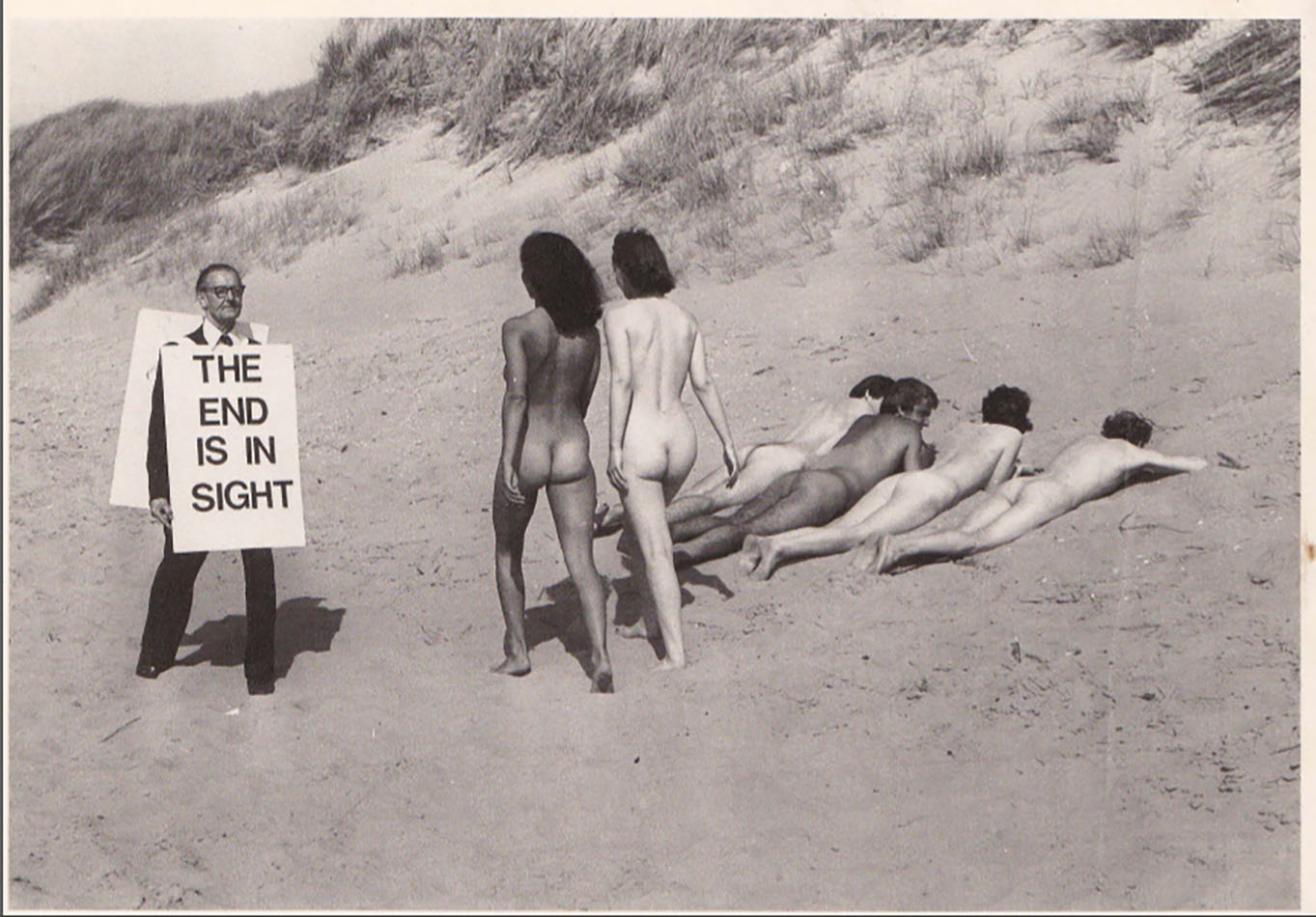

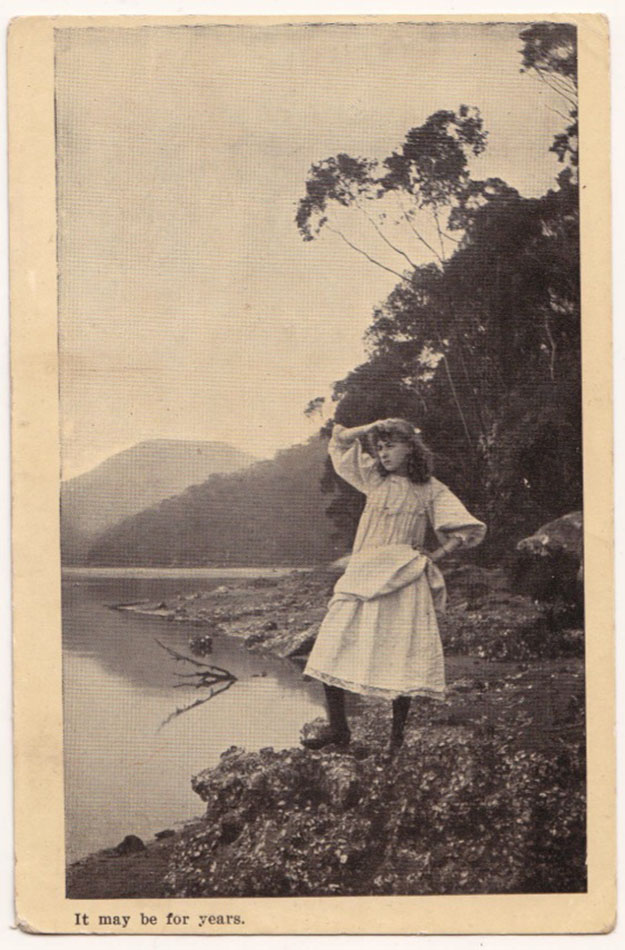

Other photographs in the collection exhibit a clear interest in manipulation and experimentation, such as Scissors, in which the heads of two men have been cut out and superimposed on the bodies of two women; contiguous with the print, it appears the jokester was no newcomer to the photographic process. I also seek out photographs distinguished by suggestive relationships between image and text, whether in the form of inscriptions, or text within the image itself. At times, inscriptions lend a seemingly mundane snapshot a darker atmosphere, as in Echo Point, taken in the Blue Mountains and inscribed “Echo Point Lookout […] This is place [sic] where two people have dropped over lately.” In other photographs, such as Nudists; or, the apocalypse is nigh, the written word is central to the image itself, pitting doomsday preachers against nudists in an absurdist vein.

The collection reflects my longstanding passion for history, photography, storytelling, and writing. I began collecting ‘found photographs’ in 2009 as an undergraduate student in History at the University of Sydney completely captivated by images of the past. I quickly came to find the process of collecting itself fascinating. Carefully picking my way through boxes of photographs unmoored from history became a means of reflecting upon the essential contingency that shapes the stories we tell about ourselves, and the archives that serve as their repositories. In equal measure, collecting photographs is, for me, a deeply associative and imaginative exercise. A vital part of the collection is experimenting with form: pairing photographs to explore visual and thematic relationships, creating titles for individual photographs that highlight specific details or capture their mood, and setting images to lines of poetry or music. Many of the items in the collection reflect my attraction to the aesthetics of earlier photographic technologies and prints, and inspire my own photographic practice. As such, the collection traverses the space between history and fiction, analysis and creation.

I am honoured to receive the 2019 James David Forbes Prize, and am looking forward to working with the Special Collections Team to expand the University Library’s Photographic Collection.

Antares Wells

MLitt History of Photography, 2018-2019

Biography

Antares Wells is a recent graduate of the MLitt History of Photography program in the School of Art History at the University of St Andrews (2018-2019, with Distinction). In September 2019, she received the O E Saunders Memorial MLitt Dissertation Prize for her thesis on the non-commissioned colour photography of Saul Leiter. Prior to her studies at St Andrews, Antares worked as an exhibition researcher in the Curatorial Department of the Sydney Jewish Museum and as an editor and translator in Dresden, Germany. Drawn to the diversity and public engagement of curatorial practice, she intends to pursue further work with historical photographs in an archival or museum setting.

Are you a current student at St Andrews? Do you have a collection which you would like to tell us about? For further details, please see https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/library/special-collections/collecting-prize/

I knew Antares farher when she was a child growing up in The Hawkesbury in New South Wales Australia in the year 2000. I knew by her intelligence she was destined for academic success. Being a family historian i think The Society of Australian Genealogists would be most interested in this collection. I know a Cheeseman and will tell them about that photo displayed here.

Thank you for your lovely comment, Pamela! Two decades later and reconnected from across the world - what a surprise! The Society of Australian Genealogists has an incredible photographic collection that I hope to visit again in future. Please let us know if your Cheeseman has any connection to that photograph. I'm open to donating it to family members/direct descendants if there is an interest in that!