‘Alhallow Evin’ in Scotland

The appearance of carved pumpkins (or turnips in Scotland), spooky decorations and plentiful sweet treats marks the arrival of Halloween. In the Christian calendar, Halloween, or its many variants Hallowe’en, Allhalloween, All Hallows Eve or Alhallow Evin, is the evening before All Hallows’ Day or All Saints’ Day, the Feast of All Saints, on the 1st of November.

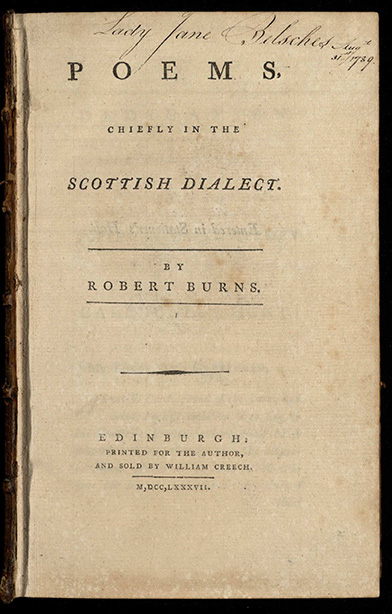

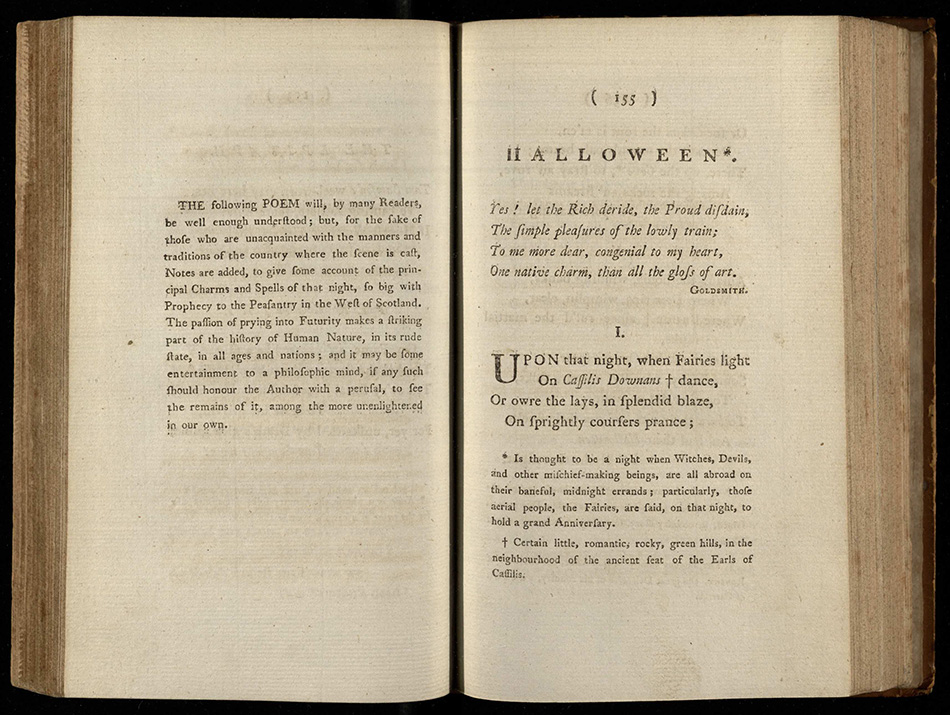

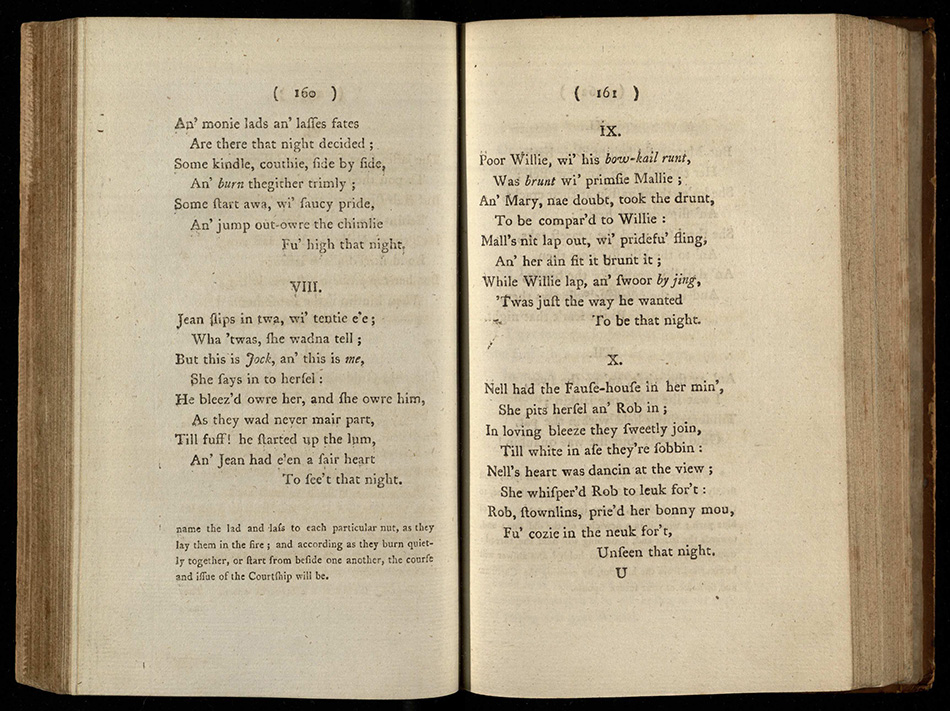

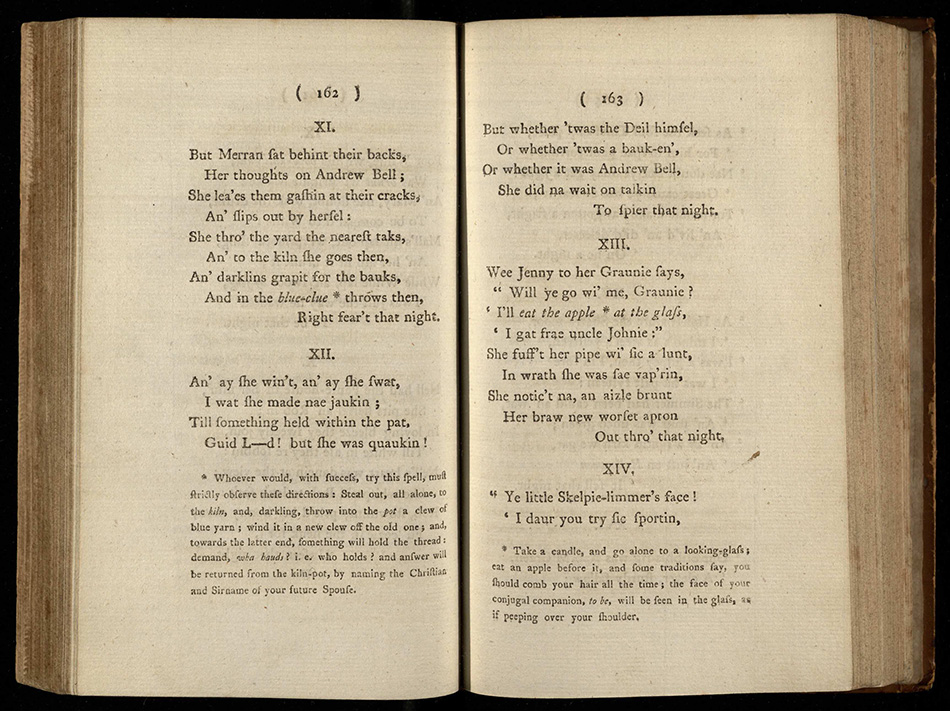

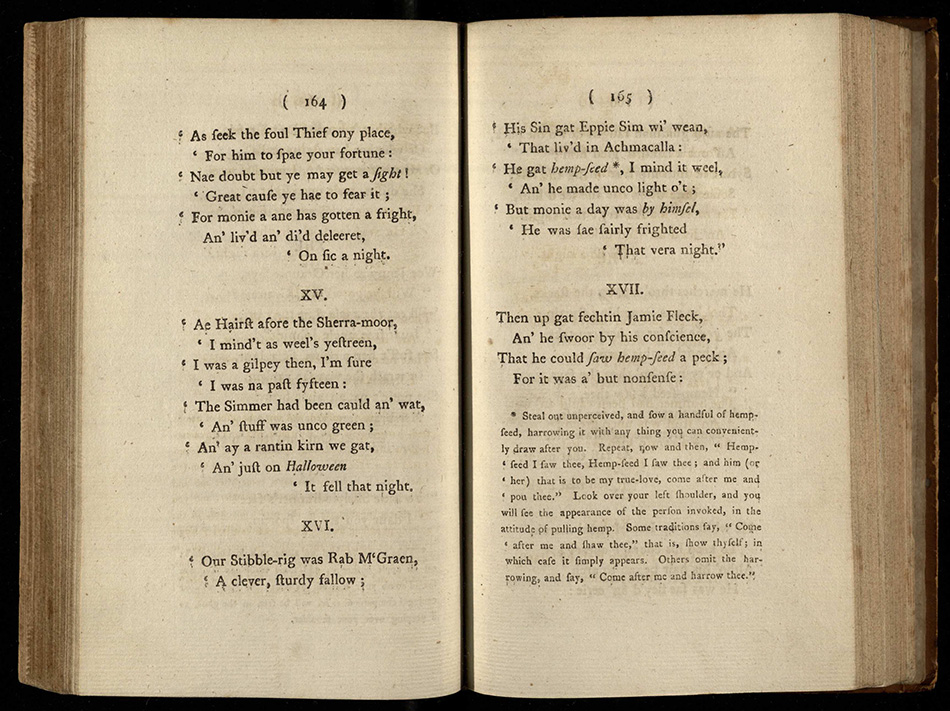

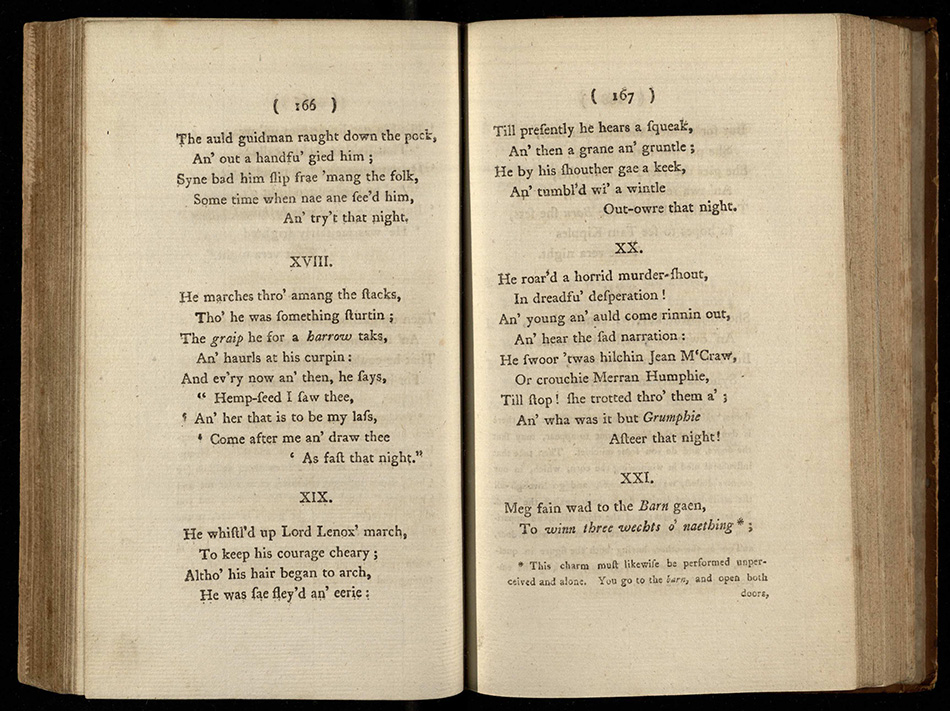

Most of us now associate Halloween with trick-or-treating, known in Scotland as ‘guising’, meaning to masquerade or go in disguise. Guisers knock on doors and are required to earn their treat by performing a song or telling a joke. In previous generations though, the day was marked with a variety of customs, best illustrated in Robert Burns’ poem Halloween, first published in the Kilmarnock edition of Poems in 1786.

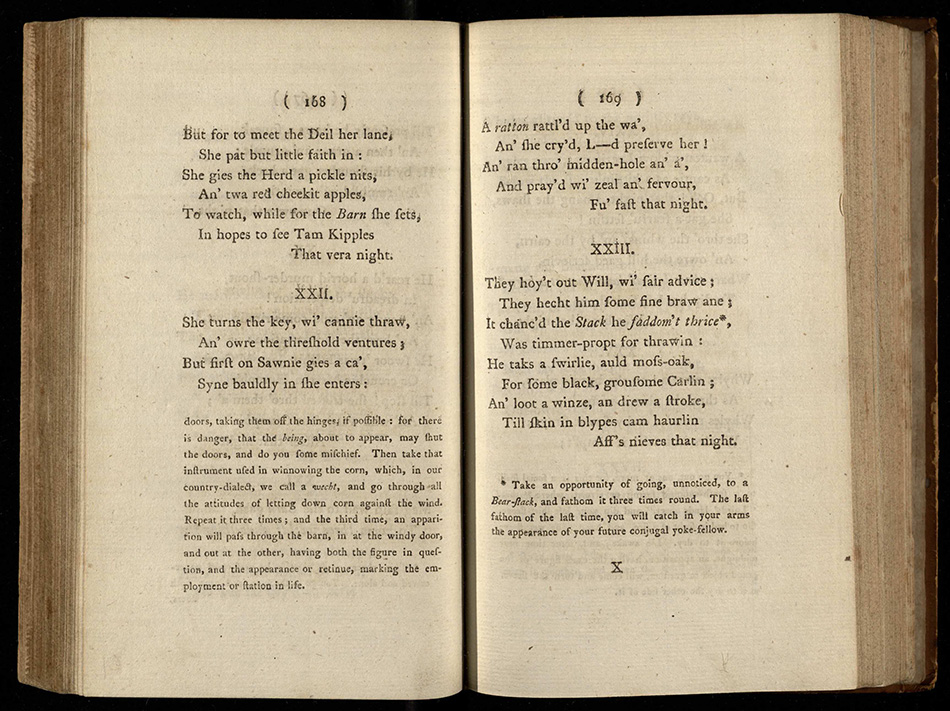

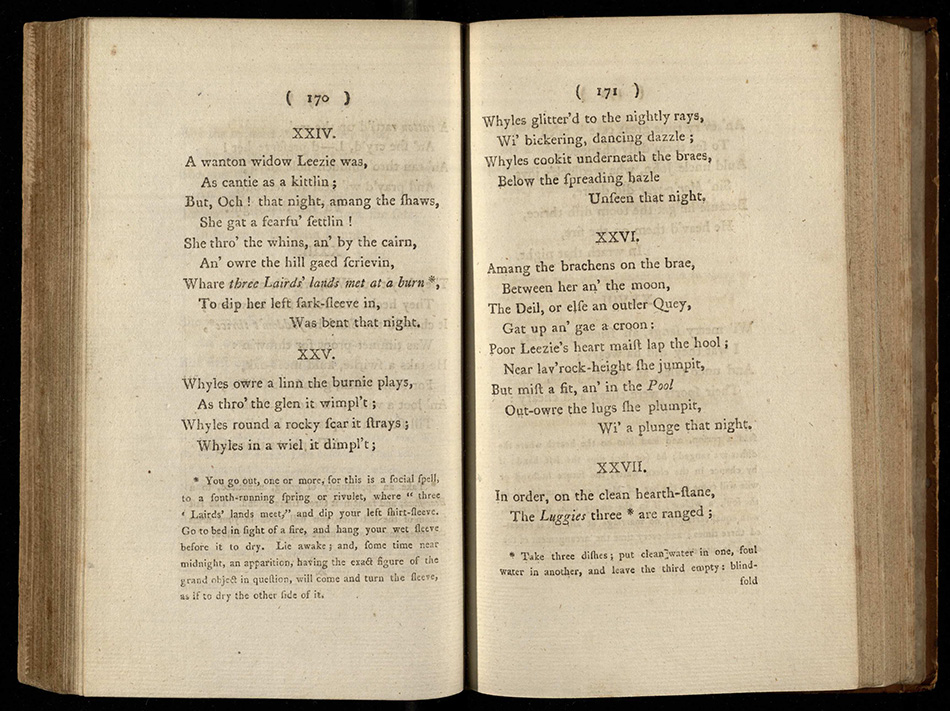

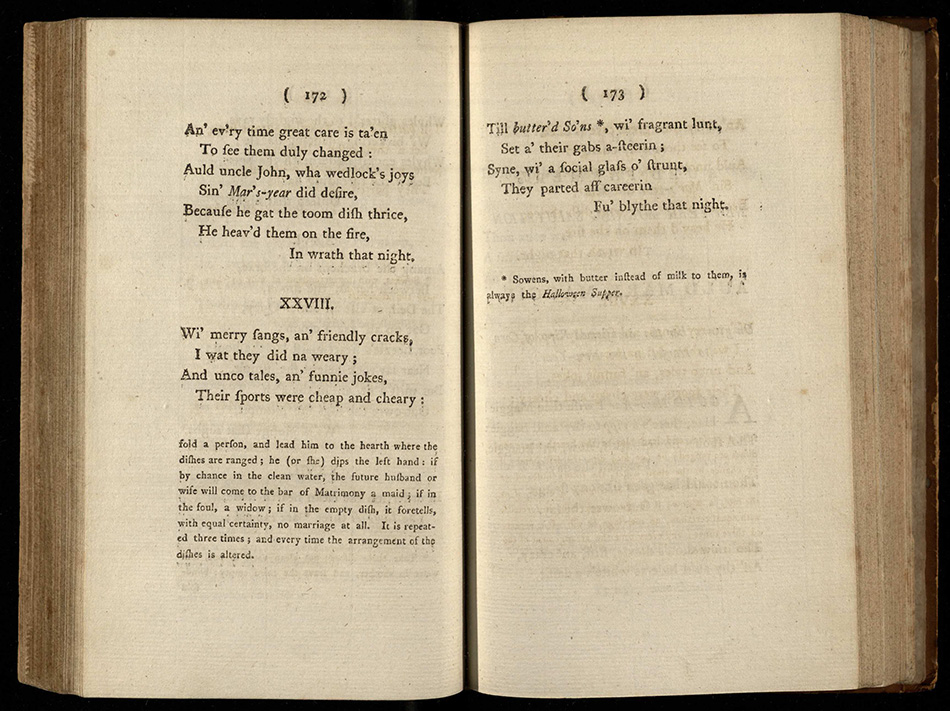

St Andrews has many editions of Burns’ works, including a copy of the 1787 2nd Edinburgh edition of Poems, chiefly in the Scottish dialect, printed by William Creech, Burns’ Edinburgh publisher and pictured above.

For the benefit of readers not familiar with the customs of those in the West of Scotland, the poem was published along with his notes

to give some account of the principal Charms and Spells of that night, so big with Prophecy to the Peasantry in the West of Scotland.

Burns’ poem was described by historian James Mackinnon in Culture in early Scotland (1892) as a ‘succinct text-book of the ancient paganism of the countryside’ [p.60]. Mackinnon’s description of the ‘ancient paganism’ documented by Burns, alludes to the connections with the Gaelic festival of Samhain, marking the end of the Harvest season and the star of the darker half of the year. Samhain, for many Scottish historians in the 19th century, was the Celtic origin of most Scottish Halloween traditions.

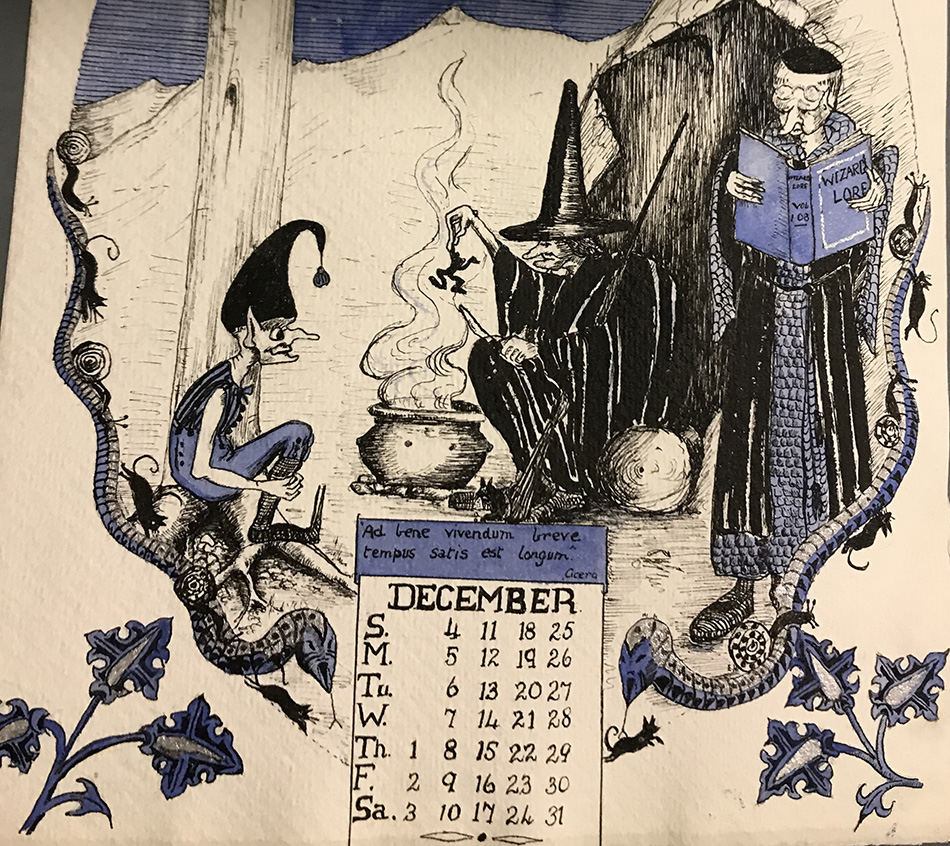

Most of the folklore around Scottish Halloween traditions was recorded by 19th century authors, some of whose works we hold in our collections. Texts such as The Popular Superstitions and Festive amusements of the Highlanders of Scotland (1823) by William Grant Stewart; Old Scottish Customs (1885) by Ellen Jane Guthrie and Folk lore: or, superstitious beliefs in the West of Scotland within this century (1879) by James Napier record many of the traditions illustrated in Burns’ poem – the majority of which focus on predicting the success of one’s love life!

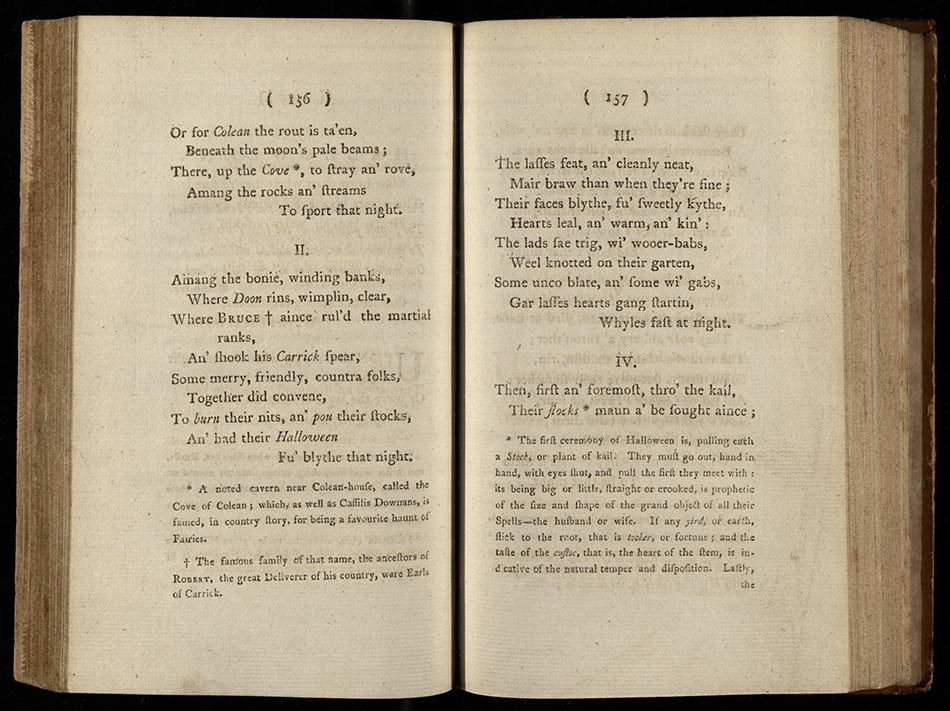

Some merry, friendly, countra folks,

Together did convene,

To burn their nits, an’ pou their stocks,

An’ had their Halloween

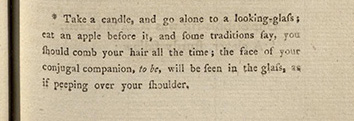

Just a few of the traditions highlighted by Burns were burning nuts, pulling kale and eating an apple in front of a mirror. To predict the success of a relationship one would throw two nuts in the fire – one signifying your name and the other the object of your affection. If they burn at the same rate, your relationship should be a success. Similarly, pulling kail [kale] stocks from the ground would predict the kind of partner you could expect and eating an apple in front of a mirror would allow you to see your future spouse.

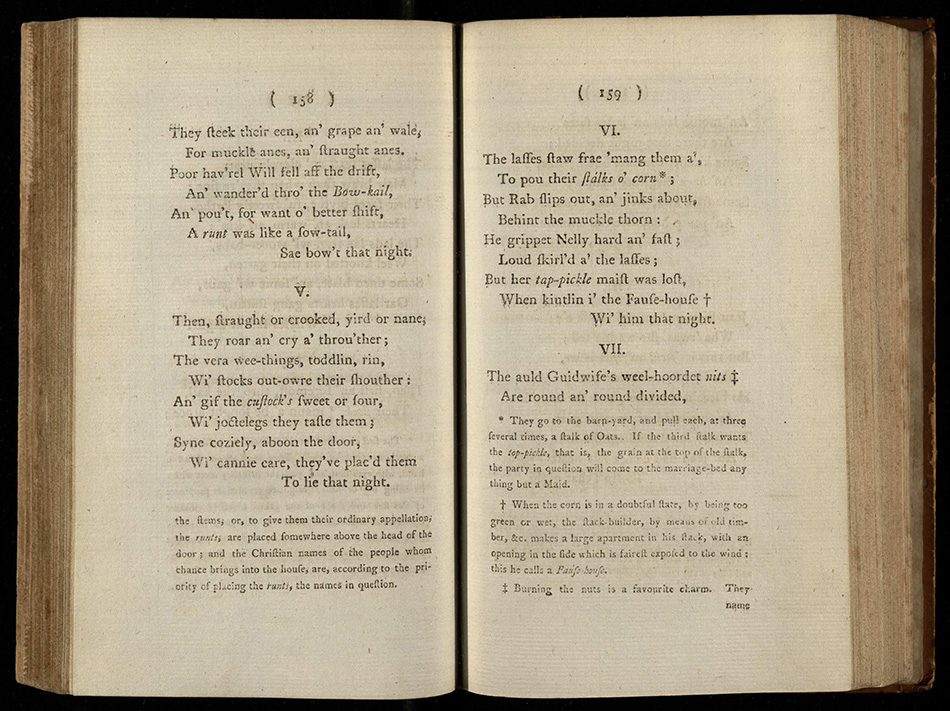

The Rev. Alexander MacGregor in Highland Superstitions (1891) declared that ‘there is no night in the year which the popular imagination has stamped with a more peculiar character than Hallowe’en’ [p.44]. Indeed, the opening line and commentary to Burns’ poem sets the scene in which Halloween is the night in which the normally invisible world holds power:

Upon that night, when Fairies light

On Cassilis Downans dance,

Or owre the lays, in splendid blaze,

On sprightly coursers prance;

Recorded references to Halloween go back to the 16th century in Scotland, including in Scottish poet Alexander Montgomerie’s 1584 poem ‘Flyting Against Polwart’. Montgomerie, like Burns, wrote of Halloween as a night in which the King of the Fairies and his court ride out:

In the hinder end of harvest, on alhallow even,

Quhen our good neighbours doth ryd, If I reid rycht,

….

The King of pharie, and his Court, with the elph queine,

With mony elrich Incubus, was rydand that Nycht.(elrich = belonging to, or resembling, the elves)

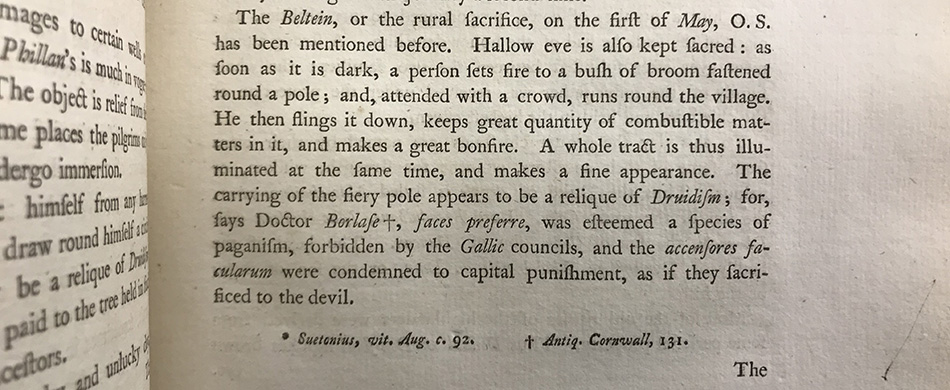

Some of documented folk lore suggests that fire was used as a defence against these invisible spirts roaming on Alhallow Evin. Like the festival of Beltane which marked the beginning of summer, Samhain was often celebrated with a bonfire, marking the end of the harvest season. Whether bonfires were used as a defence against supernatural forces or simply a celebration of the end of the harvest, it was a prevalent practice throughout the Highlands and Western Scotland, as documented by Thomas Pennant in his Tour of Scotland 1772.

While many of the titles of recorded folklore seem to suggest that the customs of Halloween are confined to the Highlands and Western coast, the tradition of bonfires appears to be widespread in Scotland.

The Rev. Thomas Bisset records the practice in the parish of Logierait in Perthshire in Sinclair’s Statistical Account of Scotland (1793). Similarly, James Napier in Folk lore (1879) recounted a visit to Loch Tay in 1860 when he witnessed, in the days leading up to Halloween, boys collecting wood and creating stacks on hills and prominent places. On the evening of Halloween, ‘both sides of Loch Tay were illuminated as far as the eye could see.’ Napier was disapproving of the rowdiness of this event and made note of how ‘the ministers set their faces against the observance’.

Church of Scotland records suggest that Halloween bonfires may have at one time been practiced in Fife. The Church of Scotland Assembly of Fife met at Cupar on the 17th of October in 1648 and ‘ordinis that intimatioun be made of the act against superstitious fyris, the Sabbath befoir Midsomer evin and Hallow evin, (as they call them).’

This order was given by Cupar Presbytery who the following year in 1649 recorded:

It is recommended to severall brethren to be carefull to intimat in

their several kirkis, wpon the Sabaths immediatly before Midsommer

and hallowewen, that no fyres be set on, wpon these nightis.

By the end of the 19th century many of the traditional Halloween customs, as Alexander MacDonald in Story and Song from Loch Ness-side (1914) commented ‘are, now, however, fast becoming things of the vanishing past’ [p.190]. This sentiment was shared by the author of the Country Notes in the St Andrews Citizen in November 1895:

The time was when Halloween, along with other observances, had a firm hold in the manners and customs of our native land…

And Halloween, hallowed in the memory of many and idolised by Burns – where is it? On Thursday night in Markinch, where the father of our correspondence has heard merry sounds and seen happy faces in assemblages met to celebrate Halloween, all was quiet. Thus do the times change, and customs with them.

- St Andrews Citizen, 30th October 1937

- St Andrews Citizen, 26th October 1929

- St Andrews Citizen, 30th October 1937

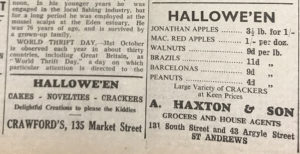

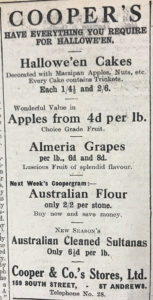

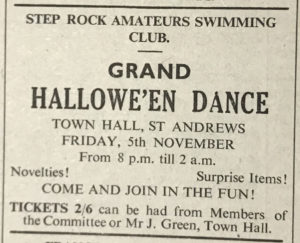

While Halloween customs may have changed over the years, Halloween still continues to be celebrated. Adverts in the 1920s-1930s encourage shoppers to purchase all that they need for the special day, including Hallowe’en cakes and apples from St Andrews’ grocery shops and local clubs held Hallowe’en dances.

George Cowie’s photographs show children ducking for apples in the 1930s and a letter to The St Andrews Citizen in November 1948 from “an old timer”, although criticising the behaviour of guisers, confirms that the practice was ongoing.

While guising and many of the old traditions may not be as common now, Halloween is still for many a chance to dress up and celebrate. Enjoy the day!

To say the least, an extraordinarily well-informed review of this peculiar time of year. Thank you very much!