Letters from a Jewish patient in the ‘German house’ in Agra in 1930s Switzerland

Ines Neffgen from Bonn spent last year in St Andrews as part of her PhD programme, working with Professor Frank Müller. She asked to volunteer in Special Collections whilst in St Andrews as she would like a career as an archivist. Taking advantage of her native German, we asked her to work on a fascinating collection of letters to and from Erwin Findlay Freundlich, founder of the University Observatory and professor of Astronomy 1951-55.

He was a Scottish/German physicist, working initially in Berlin and Potsdam with Albert Einstein, then in Istanbul and Prague before settling in St Andrews in 1939. He had to keep moving because his grandmother was Jewish and he was married to a Jewish woman, Kate Hirschberg. This made them very vulnerable in Germany and central Europe in the 1930s.

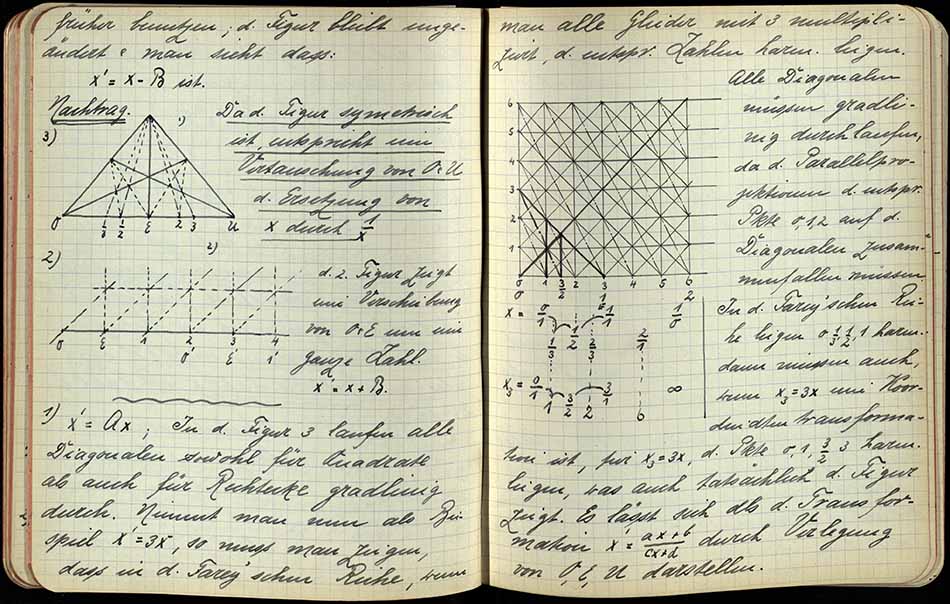

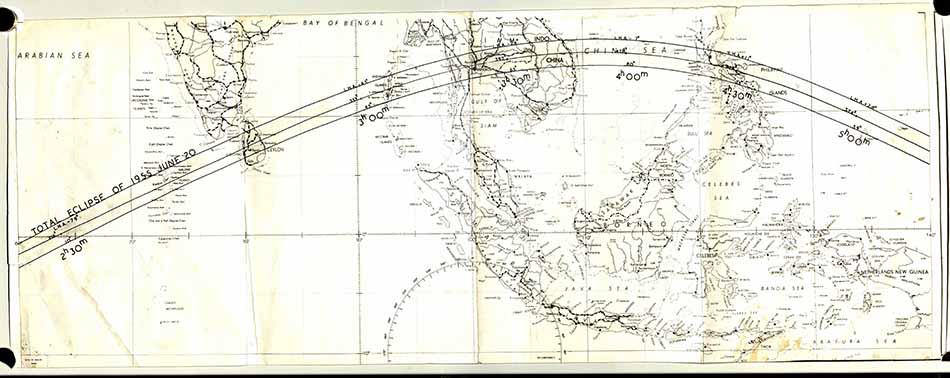

Much of the Freundlich archive is about his work in the field of astrophysics, and in fact he was responsible for installing the largest telescope in the UK at his observatory in St Andrews. You can read about a previous visit to the Observatory here.

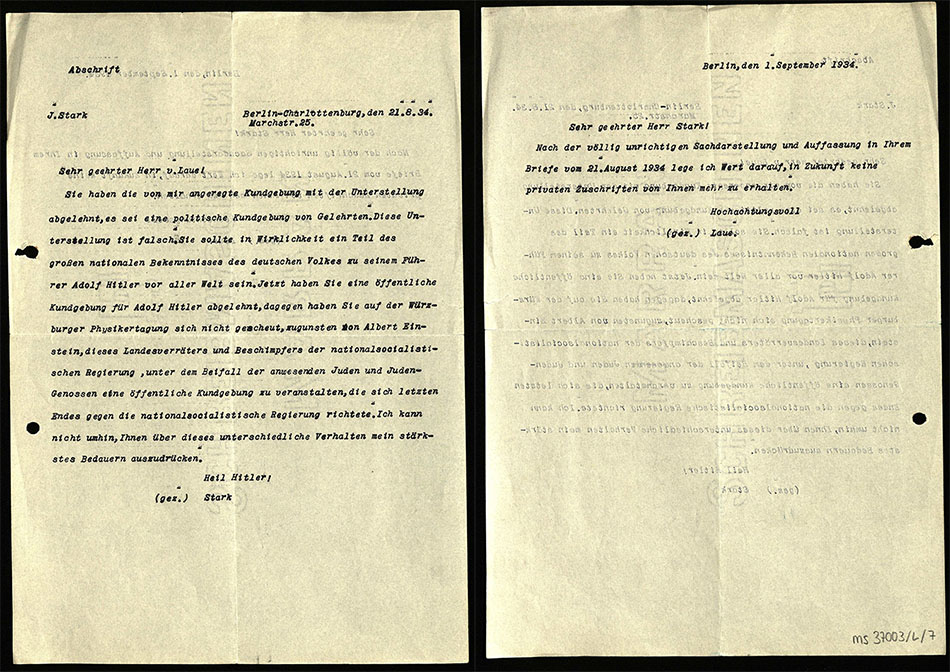

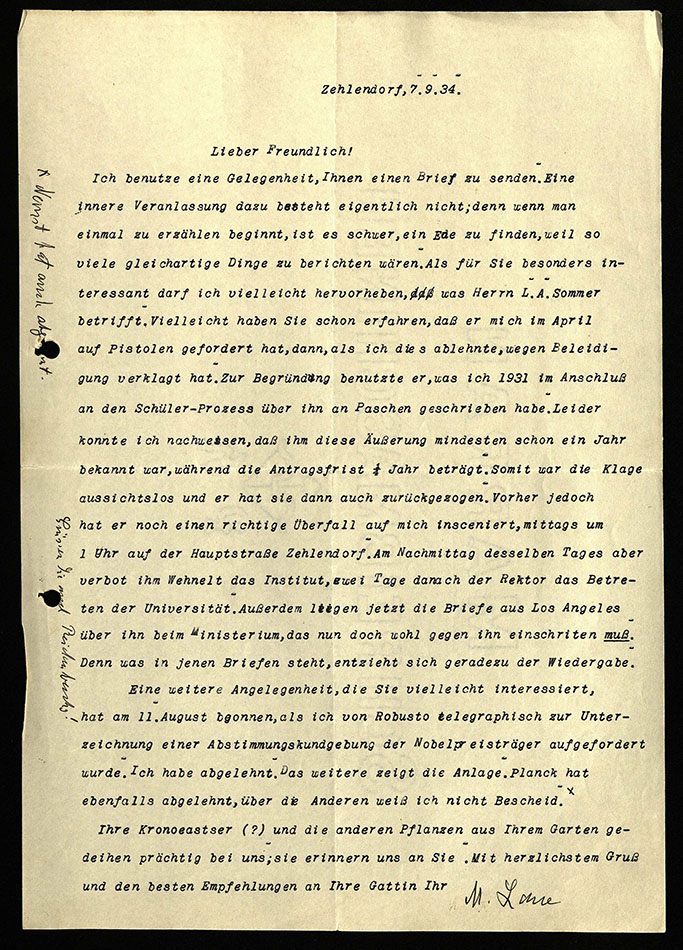

One folder of his correspondence however shows life in the scientific world under the Nazi regime in Germany. There are letters from scientists on both sides, such as Johannes Stark, a supporter of National Socialism and the Aryan movement “Deutsche Physik” against Max von Laue, a Nobel Prize winner for Physics, deprived of his University post for opposing the regime.

What follows is one of the stories that Ines uncovered during her cataloguing project.

When Lena Goldfield realized that the symptoms of her tuberculosis disease had re-appeared, she was working as a Research Assistant to the German astronomer Erwin Finlay Freundlich in Istanbul. Freundlich, whose wife was Jewish, had left the observatory in Potsdam after the National Socialists came to power in 1933. Goldfield followed him to Turkey. She had suffered from tuberculosis before and the disease could been treated in a German sanatorium. But now, due to her Jewish background, she was in need of a different treatment option.

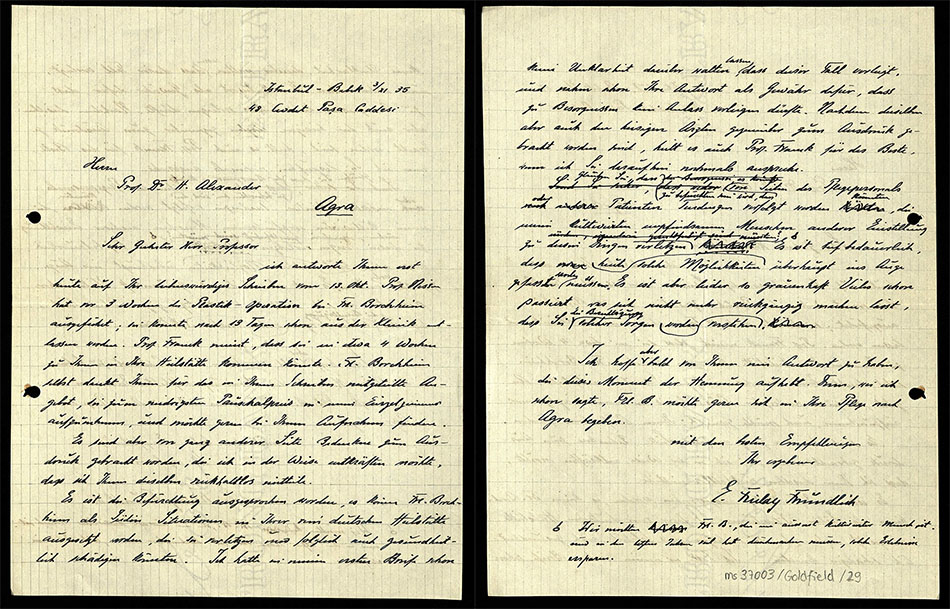

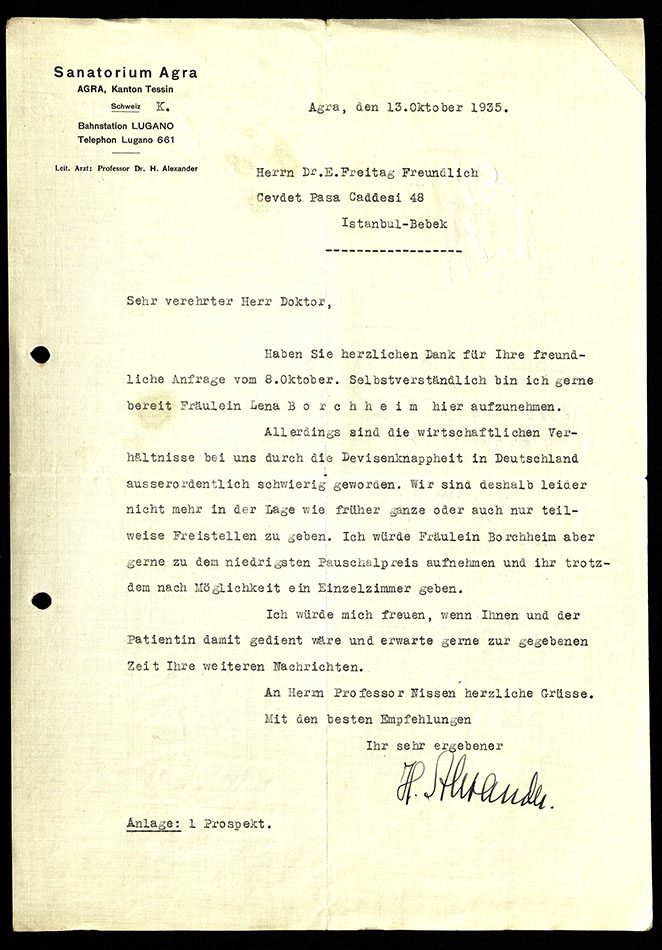

Finlay Freundlich arranged for Goldfield to stay at the tuberculosis sanatorium in Agra in Switzerland. They were full of hope that she would once again recover in the Swiss climate. In the correspondence with the doctor in charge, Professor Hanns Alexander, Freundlich explained the difficult situation and ensured that no problems would occur for Goldfield because she was Jewish. As a means to hide her identity, they used the name ‘Lena Borchheim’.

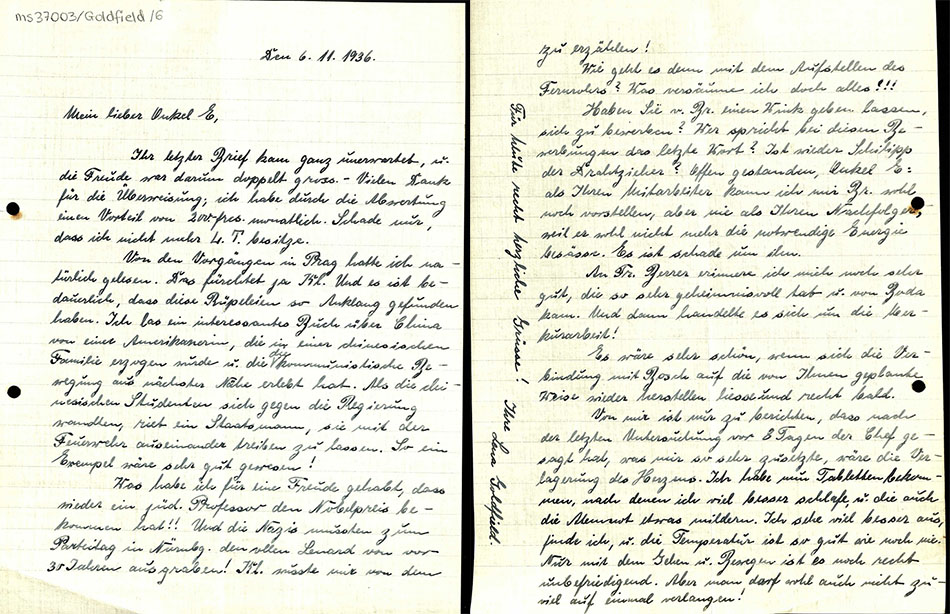

The ‘Goldfield folder’ contains 31 letters concerning Lena Goldfield’s stay in Agra from October 1935 to January 1937. The majority of the letters come from Goldfield, describing her current situation, thoughts and hopes. The letters are useful for providing an insight into life at the sanatorium and the medical treatment of tuberculosis at this time.

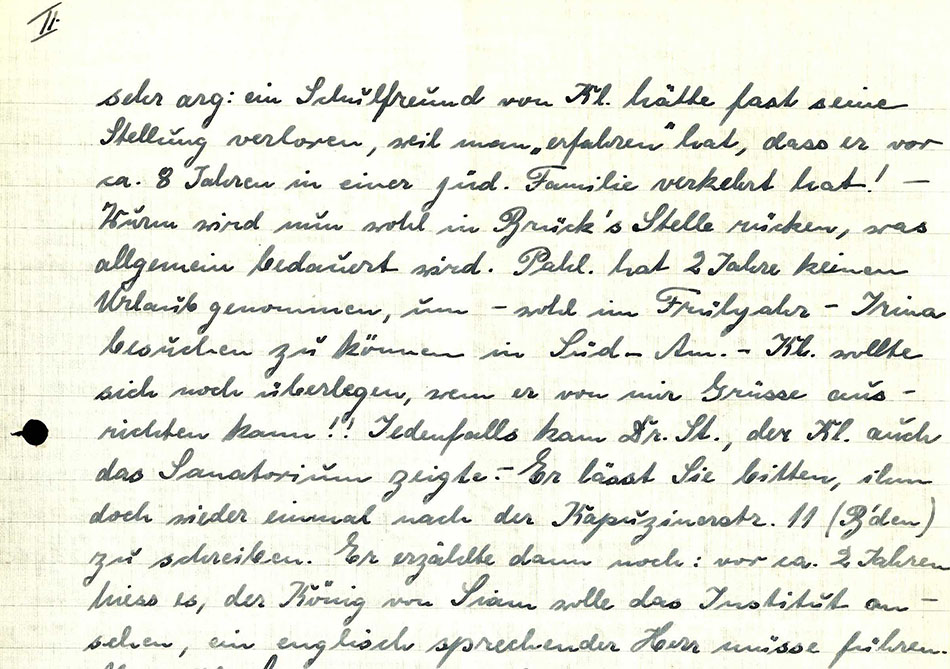

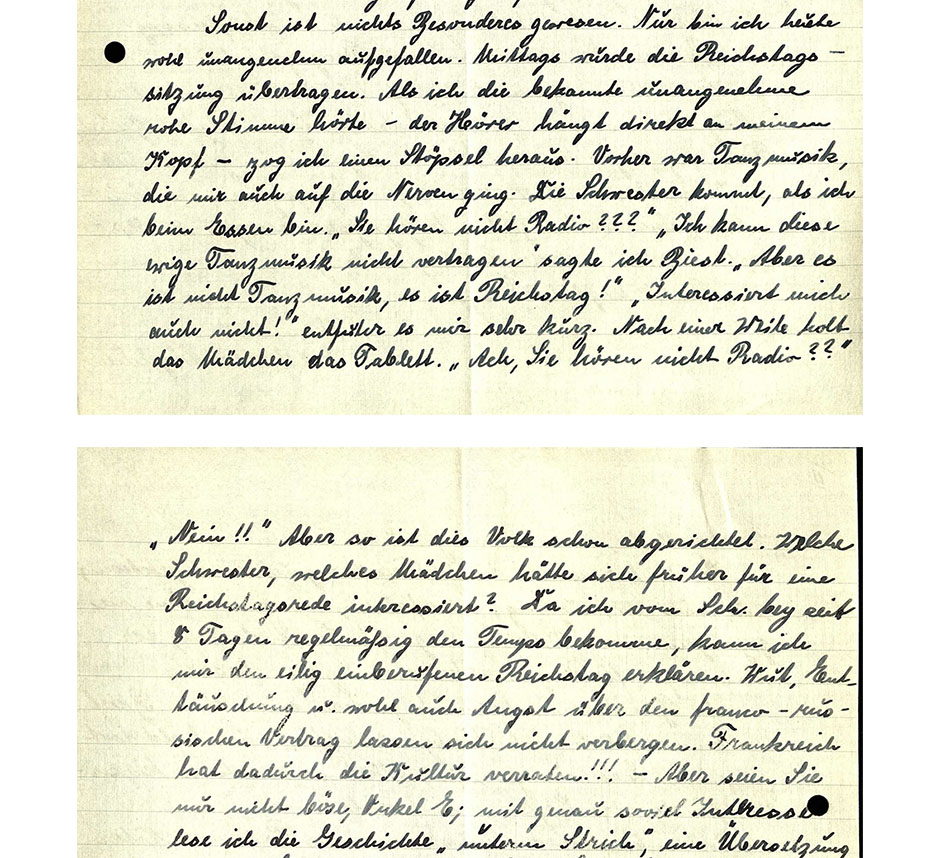

Although Goldfield stayed in Agra, she remained concerned that someone would find out that she was Jewish. Additionally, she also closely and anxiously followed political developments.

In one particular letter, she reported to Freundlich that she strongly felt that she had attracted negative attention from the nurses, for she had refused to listen to the radio broadcasts from the Reichstag unlike everybody else. In her letter Goldfield notes that people had been politicized in a way that was new: “Which nurse, which girl would have been interested in a Reichstag speech previously?” she asks ironically (ms37003/Goldfield/19).

The ‘German House’ in Agra had been a well-known place for tuberculosis therapy. Patients were treated there from 1913 to 1968. The sanatorium, however, was financially dependent on Germany. Therefore, the on-going political situation also affected the house in Agra. In 1937, the physician Hanns Alexander became the local group leader of the NSDAP. As the case of Lena Goldfield shows, however, at least until that year Jewish patients were still unofficially treated in Agra.

In Goldfield’s case, the treatment was unsuccessful. In her last letter to Freundlich in January 1937, she explains that she would end her suffering on her own accord as there were no chances of recovery left. She was also concerned that her new physician would be prejudiced against her and perhaps this played on her mind, driving her to hopelessness and suicide.

Finlay Freundlich and his family moved first to Prague and then on to St Andrews in 1939. At St Andrews Freundlich set up the Department of Astronomy with the Observatory and stayed in Scotland until he retired in 1959. His papers give an insight into the life of a scientist in the 1930s, as well as providing a deeper insight into his broad network and connections with many other scholars who felt compelled to leave their country during the time of National Socialism.

We are grateful to Ines for her work on the Freundlich collection and wish her well with the completion of her PhD and her future career.

For further reading:

An article in German on the Agra sanatorium with haunting photographs: https://www.spiegel.de/einestages/alpensanatorium-agra-a-948807.html

Erwin Freundlich was indeed in danger in his post at the Charles University in Prague, where he had built a telescope. The danger was compounded by the fact that not only was his wife a Jew, but he and his wife had adopted the Jewish orphan children of his wife's sister: Hans and Renate. Erwin Freudlich was able to come to St Andrews because the Cambridge mathematician, A.S. Eddington knew of the Freundlich family's danger and he approached his friend, Sir James Irvine, Principle of St Andrews, with the request that he help this outstanding man. Luckily the Department of Astronomy lay waiting to be developed and Freundlich famously built up St Andrews distinguished astronomy department. I remember Professor Freundlich well; he was a kindly presence in St Andrews.

Fascinating post. My Master's dissertation was on W.G. Sebald, so I am very interested in pre-WW2, pre-Holocaust Europe, and in particular the warp and weft of Jewish culture that Europe has lost.

My thanks to the learner-scholar for her work!