‘The teaching of politics at the University of St Andrews, 1600-1650’

In the final report by our 2019 visiting scholars, Karie Schultz reflects on her time at St Andrews.

Earlier this summer, I had the opportunity to spend two weeks at the University of St Andrews Library’s Special Collections as a visiting scholar. The research I undertook focused on manuscript student notebooks and lecture notes related to the university curriculum at St Andrews from 1600 until 1650. More specifically, I examined how early seventeenth-century university-educated Scots (often noblemen, ministers, and lawyers) were taught about human agency in political life through classical and medieval philosophy.

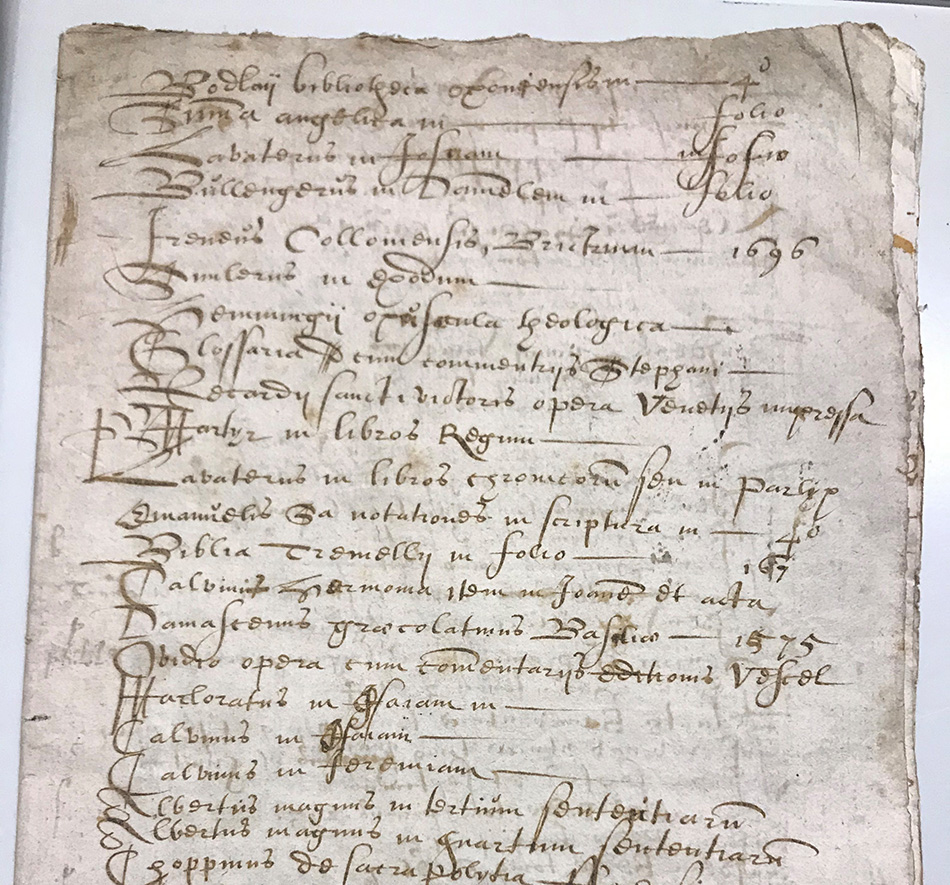

Students entered the universities at a young age––usually 13 or 14 years old–– where they were introduced to works by classical authors, such as Aristotle, Plato, and Cicero. They underwent rigorous training in a variety of disciplines that included logic, rhetoric, and physics (amongst others). Students were additionally taught Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Politics so they might learn how to contribute positively to the civil kingdom as godly individuals who encouraged their fellow citizens to act virtuously. At St Andrews, I focused specifically on the teaching of such ideas about politics and virtue through three different types of manuscripts: student notebooks, lecture notes, and library catalogues. Drawing upon these sources, I sought to determine which resources Scots had available in their ‘intellectual toolbox,’ so to speak, that they could draw upon to express their views on political resistance during the British civil wars of the 1640s.

I spent the majority of my time working with four sets of student notebooks––ranging from 1620 until 1646 in date––to clarify the connection between university education and political allegiance during the civil wars (msLF1112.S4, msLF1112.C42, ms38297, and msBR85.S5). These sources provide a record of the types of doctrines that were taught in the university classroom and the ways in which students engaged with classical authors.

The teaching of ethics and politics in Scottish universities had practical implications for political discourse; Scots wrote lengthy treatises throughout the late 1630s and the 1640s in which they debated the legitimacy of resisting King Charles I and his ecclesiastical reforms. The ideas about political life, honour, virtue, and law that run throughout these student notebooks and lecture notes offered Scots on all sides of the conflict an intellectual framework for understanding their allegiance and duty to the civil magistrate.

From my work with these manuscripts, I was able to determine that Scottish students were taught about the extent to which humans should willingly engage in political life to exercise their own rationality and the extent to which government was simply a duty or obligation imposed by God. Students were also exposed to various interpretations from Aristotle, Cicero, and Plato about what human beings should seek in political life. Lastly, there was a general consistency in how these ideas were taught across all Scottish universities in the period. But Scots chose to employ these ideas in different ways during the 1640s. They ultimately made conscious and selective choices about which ideas and sources from their education to draw upon and use in new ways to defend their allegiances.

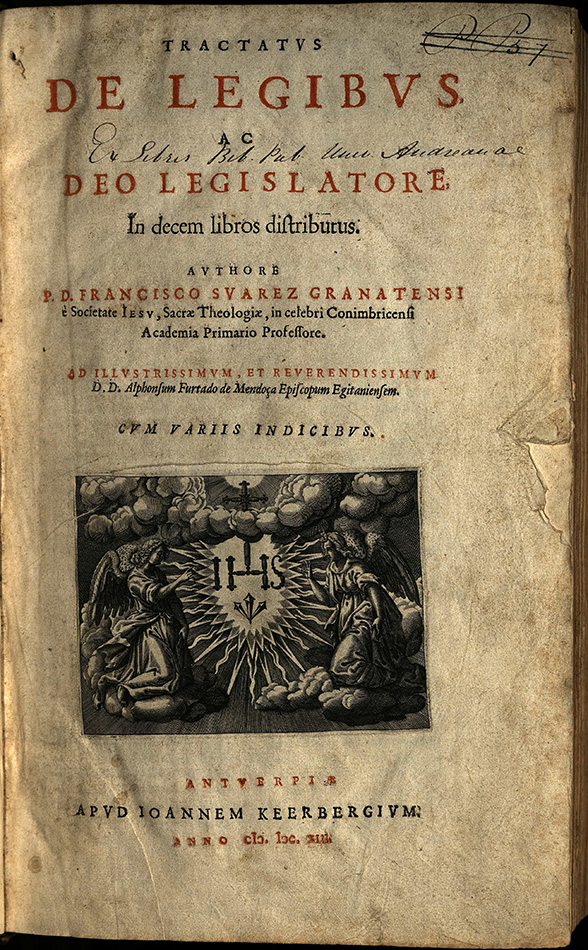

I also supplemented these student notebooks and lecture notes with library catalogues to gain an idea of which texts by continental European Catholic and Protestant scholars would have been available to students through the University library in the first half of the 17th century. The earliest catalogue from St Andrews which dates from 1644 demonstrates that students had access to many biblical commentaries by Protestant authors and treatises on law by Catholic authors, most of which dealt with questions about the origins of civil authority and the legitimacy of resistance. For example, we know that the library included a copy of Francisco Suárez’s Tractatus de legibus ac Deo legislatore from 1613 (Roy BX890.S8). This text substantially informed Covenanter Samuel Rutherford’s ideas about the origins of government in his famous Lex, Rex; or, the law and the prince (1644). Rutherford was Principal of St Mary’s College in the University (1639-61). While we cannot be certain of the extent of readership from the catalogues, we do know which library sources were available for students and staff to use, sources that often appeared later in treatises about resistance or obedience in the civil-war context.

Overall, the manuscripts I worked with were challenging but rewarding. They are all written in Latin and in secretary hand, a form of handwriting common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Many secretary-hand letters are unrecognizable to the modern eye, so special palaeography training is essential. Given their dense philosophical content, coupled with readability challenges, these sources remain understandably underutilised by historians of early modern Scottish history. However, thanks to the visiting scholarship, I was able to spend the time needed at St Andrews to study these manuscripts in great detail (including many hours simply trying to decipher handwriting). I also had the opportunity to work closely with the university archivists––particularly Rachel Hart––who were incredibly helpful in providing background context for developments at the University from its foundation through the seventeenth century and who frequently recommended additional archival material. I now intend to include this research in the first chapter of my doctoral dissertation about intellectual life in Scotland from 1600 until 1650.

I am incredibly grateful for the time I was able to spend at St Andrews this summer, and I hope that the work I conducted on these manuscripts will shed light on just some of the early modern manuscript treasures held by Special Collections.

Karie Schultz

PhD Candidate, History

Queen’s University Belfast