USTC Conference: Gender and the Book Trades Part III

In this third instalment from our virtual showcase for the USTC Conference ‘Gender and the Book Trades’ we highlight some of the items from our collections which women authored.

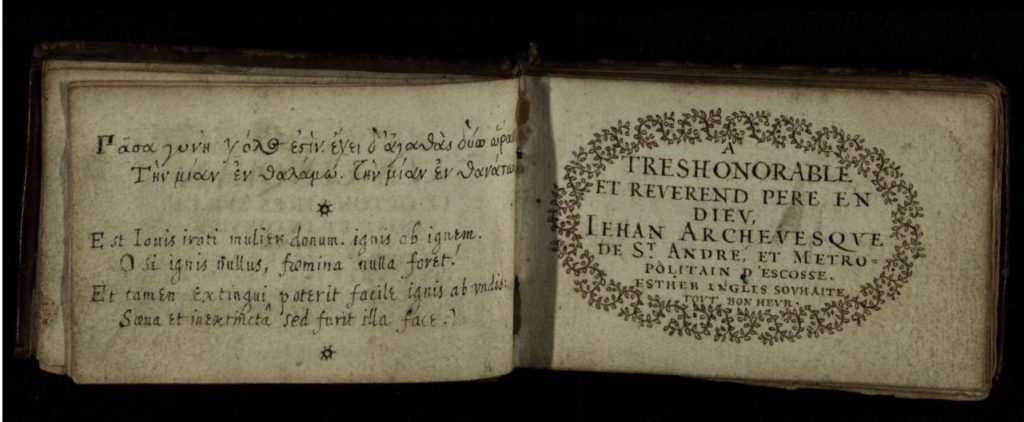

In 2011 we purchased a wonderful miniscule manuscript (ms38830) created by the well-known calligrapher Esther Inglis (1571-1624). It consists of 50 eight-line poems by the Huguenot Antoine de la Roche Chandieu (1534-1591). Inglis crafted these small manuscript books as gifts to people in positions of power and influence, in the hope of either financial reward or patronage for her husband, clergyman Bartholomew Kello. Our copy was dedicated to John Spottiswoode (1565-1639), who became Archbishop of St Andrews and Primate of Scotland in 1615. It may also have belonged to a daughter of Archbishop James Sharp (1618-1679), Spottiswoode’s successor, as there are ownership inscriptions by an Elizabeth Sharp. As she copied text and illustrations Inglis might not be considered an author in the accepted sense, but she was certainly a talented craftswoman. You can read more about our manuscript here.

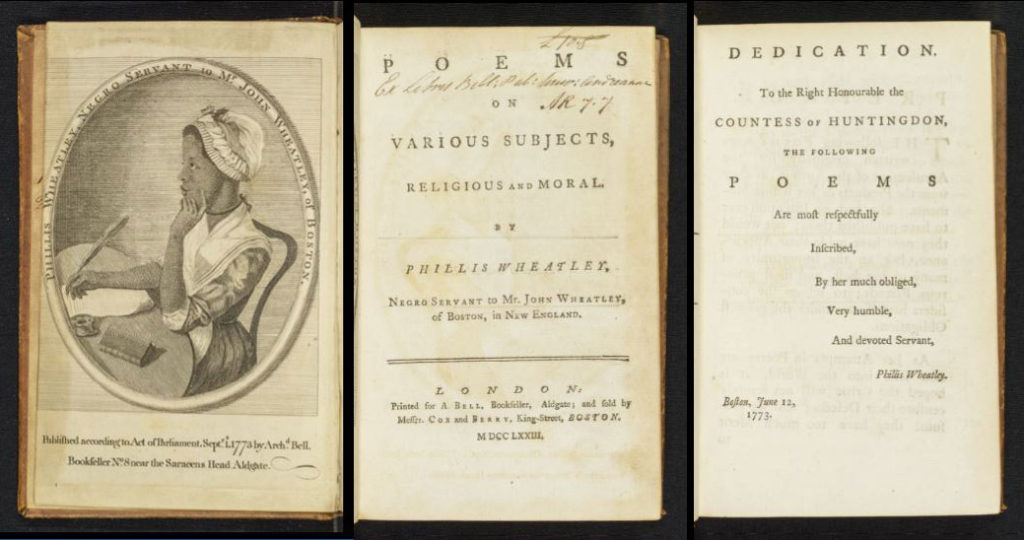

Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753-1784) was born somewhere on the banks of the Gambia River, probably of aristocratic parentage. She was only 7 or 8 years old when she was sold on the block ‘for a trifle’ to John and Susanna Wheatley, who named her after the slave schooner the Phillis, which had brought her from Africa to Boston. According to a letter from John Wheatley, published in her 1773 Poems on various subjects (St Andrews copy s PR3763.W934), Phillis mastered the English language within 16 months of her arrival in America, “without any Assistance from School Education, and by only what she was taught in the Family.” She learned to write within a short time too, and had “a great Inclination to learn the Latin Tongue” in which she made some progress. The poems are dedicated to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, and it’s probable that she subsidised their publication, for she had encouraged Phillis to seek a London publisher after attempts to publisher her poetry in Boston failed. Verbal parallels between her verse and that of Mather Byles (1706-1788), an American clergyman, suggest that he may have acted as her tutor and poetic advisor. Phillis’ Poems was reviewed favourably in London at least nine times before the end of 1773, and was reprinted many times in England and America during the 18th and 19th centuries.

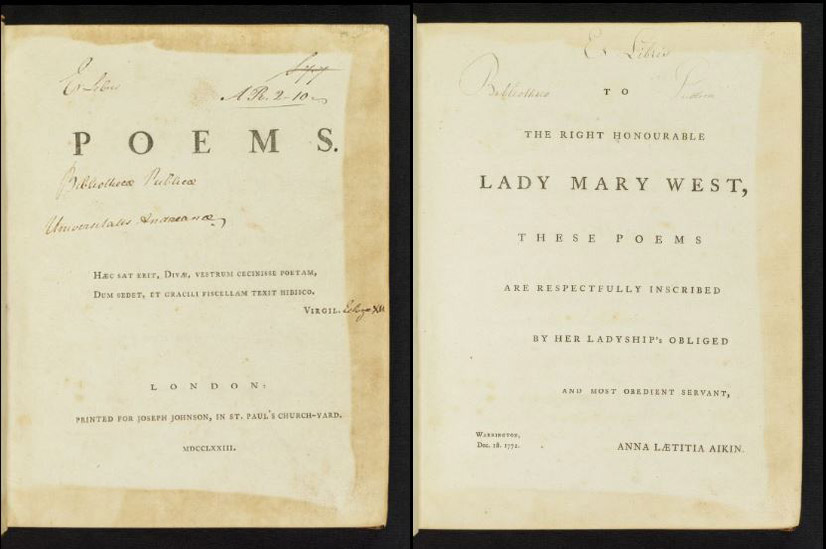

Anna Letitia Aikin (1743-1825), better known as Mrs Barbauld, was educated by her mother, who taught her to read by the age of two. She persuaded her father, headmaster of the dissenting academy in Kibworth Harcourt, Leicestershire and minister at a nearby Presbyterian church, to teach her Latin and some Greek. In 1758 the family moved to Warrington; inspired by the intellectual atmosphere of that town, and encouraged by her brother John Aikin (1747-1822), with whom she shared literary and scientific tastes, Anna began, around the mid-1760s, to write poems. Published in 1773 by Joseph Johnson, her Poems was a popular and critical success, reaching five editions by 1777, and winning the adulation of the Monthly Review, and the admiration of women readers. It wasn’t until the new edition of 1792 by publisher Joseph Johnson (1738-1809) that Anna’s name appeared on the title page (although James Magee included it in his edition published in Belfast in 1774).

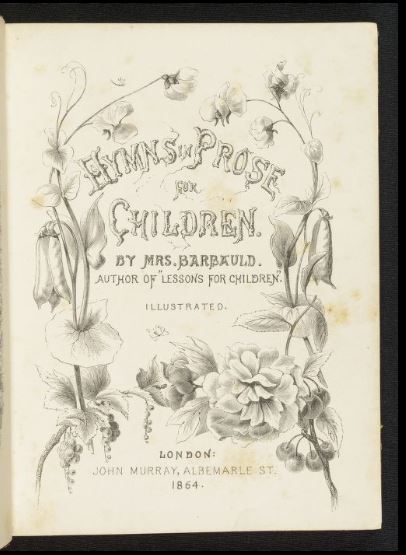

In May 1774 Anna married the Revd Rochemont Barbauld, and in July they opened a school for boys, which was a great success, drawing pupils from as far away as New York and the West Indies. It was whilst running the school that Mrs Barbauld penned her most influential books: Lessons for Children (4 vols., 1778–79), written to teach their adopted son Charles to read, and Hymns in Prose for Children (1781), a primer in religion for her youngest pupils. Reprinted in England and America throughout the nineteenth century, and translated into other languages, these works profoundly affected reading pedagogy among the middle classes, and the name “Mrs Barbauld” became virtually synonymous with infant instruction. The Barbaulds resigned from the school in 1785, and by 1790 Mrs Barbauld’s published writing focused primarily upon political and social concerns.

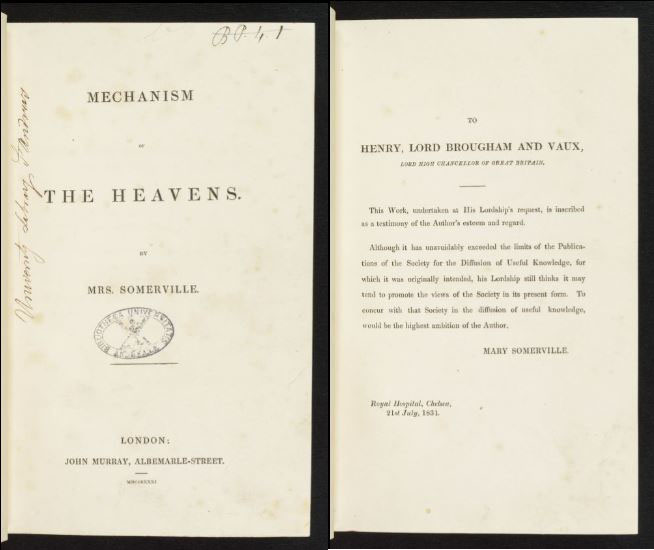

Women took an interest in the sciences, and one such was Mary Somerville (1780-1872), who had a great interest in mathematics. She was mainly self-taught, using the small family library. In her early teens she acquired Euclid‘s (fl. 300BC) Elements of Geometry and John Bonnycastle‘s (1751-1821) Algebra which she studied in secret, her father having forbidden her to read mathematics. Mary’s first husband, a cousin, Samuel Greig (1777/8-1807) didn’t encourage her to study maths, but her second husband, William Somerville (1771-1860), another cousin, did. Her first scientific publication appeared in 1826, and the paper established her as someone active in scientific work. The following year Henry Brougham, an influential figure in London educational circles, asked Mary to prepare for publication a condensed English version of Pierre-Simon Laplace‘s (1749-1827) Mécanique céleste (published 1798–1827), for an educational series. Brougham’s request to Mary was no minor matter. Mary worked on the project for three years, consulting often with astronomer Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) and mathematicians Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) and Charles Babbage (1791-1871). Her completed work covered the first four of Laplace’s volumes, but Brougham decided it was too long for his low-cost series. However, upon Herschel’s recommendation the publisher John Murray accepted it. The Mechanism of the Heavens appeared in 1831 and was generally well received. In 1832 the largely non-mathematical introduction, which Somerville considered her most important contribution, was published separately as Preliminary Dissertation to the Mechanism of the Heavens.

Her second book On the Connection of the Physical Sciences was published by Murray in 1834, and was immensely successful, with subsequent editions in 1835, 1836, and 1837. Her next work was Physical Geography, published in 1848. This was the first English language textbook on the subject of physical sciences. Although preceded by the first volume of Alexander von Humboldt‘s (1769-1859) acclaimed Kosmos in 1845 (of which St Andrews has two copies), it was an immediate success, and remained in use as a textbook until the early 20th century. One of St Andrews’ copies of Physical Geography (For GB54.S6) was formerly owned by the eminent scientist James David Forbes (1809-1868), and was presented to the library by his son, George, in 1929, along with the rest of Forbes’ library.

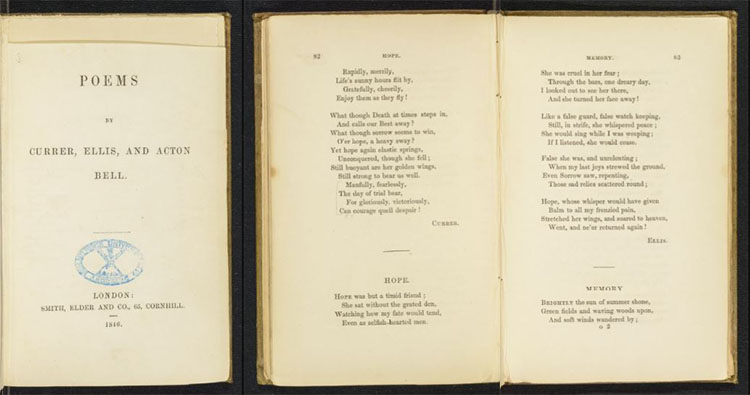

One of the most famous trio of female writers in the 19th century were the Brontë sisters, Charlotte (1816-1855), Emily (1818-1848), and Anne (1820-1849). Unlike most middle-class Victorian households, there was little censorship of reading in the Brontë parsonage, with eclectic reading being staple fare. Their father, Patrick Brontë (1777-1861), also encouraged them to explore the moors and to take an interest in natural history. In September 1845 Charlotte made her famous discovery of one of Emily’s notebooks of poetry, and persuaded her very secretive sister that they merited publication. Together with Anne, the three sisters made a selection of their verses, polishing the poems for publication. They chose pseudonyms designed to avoid criticism based on their gender. Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell appeared in May 1846, published by Aylott and Jones at the authors’ expense (£31 10s). Our copy is a reissue, in 1848, by Smith, Elder and Co. – although the title page claims 1846. Only two copies of the first edition were sold, yet several favourable reviews, and the satisfaction of seeing their work in print, provided the stimulus needed for the sisters to pursue their ambitions as authors.

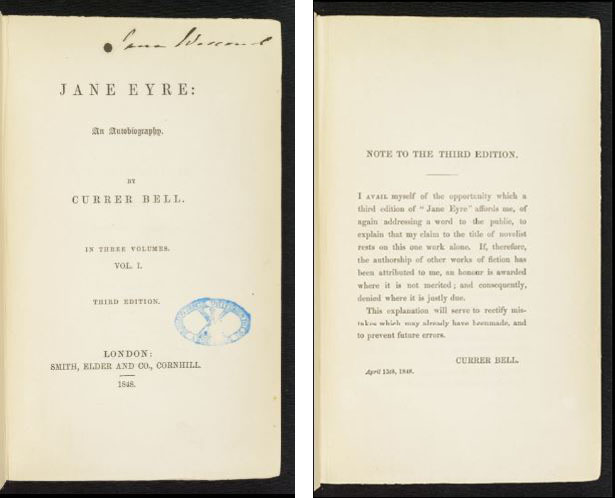

When Charlotte published Jane Eyre in October 1847, speculation was rife about the identity of the author and whether or not it was the work of a woman. Upon choosing a male pseudonym, Charlotte had only a vague idea that women writers were looked on with prejudice. She was shocked to find that even her mode of thinking was viewed by critics as ‘unfeminine’. Thomas Newby, who had published Emily and Anne’s Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey in December 1847 (capitalizing upon the success of Jane Eyre, whose author was clearly related to Ellis and Acton Bell), embarked on a clever but unscrupulous advertising campaign in 1848 to confuse the identity of the three Bell ‘brothers’, suggesting that the novels – including Anne’s Tenant of Wildfell Hall, published in June that year) – were the work of one person. Charlotte and Anne travelled to London to confront Newby with his lies and to allay the concerns of Smith, Elder & Co., by proving their separate identities.

The Library of the University of St Andrews is fortunate to hold many editions of the works of the Brontë sisters. The majority are found within the Hargreaves Collection, and you can read more about this collection here.

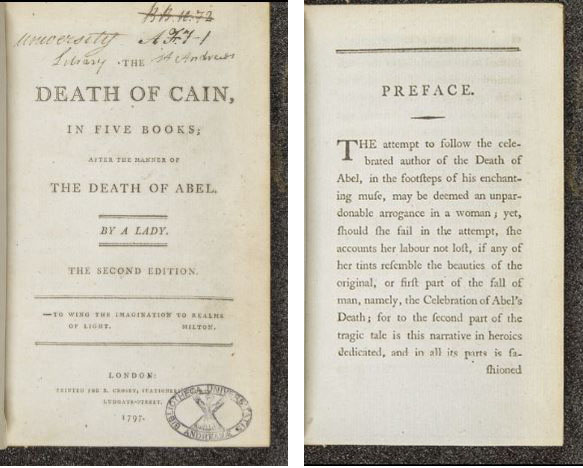

Whilst some women chose to publish under their own name, and some under a male pseudonym, there were others who used the pen name ‘by a lady’ (sometimes with the adjective ‘young’, or in one instance in our catalogue ‘country’- the author of Females of the present day). The Death of Cain, first published in 1789 by ‘A Lady’ (our copy is the second edition of 1797), clearly seems to fall into this category, of a woman concealing her identity. Yet this is not the case. The author is actually William Henry Hall (d. 1807). Hall was clearly intending to cash in on the successful translation by Mary Collyer (ca. 1716-1763) of Salomon Gessner’s (1730-1788) Der Tod Abels in 1761, and to do so by using a female pseudonym.

The Uruguayan poet Delmira Agustini (1886-1914) began writing when she was ten and had her first book of poems published when she was still a teenager. She considered the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío (1867-1916), the father of the modernism literary movement, to be her teacher. Agustini specialised in the topic of female sexuality during a time when the literary world was dominated by men. Her writing style is best classified in the first phase of modernism, with themes based on fantasy and exotic subjects. Agustini’s work was translated by Valerie Martínez (b. 1961), and published as A flock of scarlet doves in 2005 by the Sutton Hoo Press. A limited edition of 150 copies, it is printed on Japanese hand-made paper, and is illustrated with lino-cuts designed and printed by the artist Adrián Tió.

The title page of Agustini’s A Flock of Scarlet Doves, with one of the lino-cuts by artist Adrián Tió. This is our only work by the Sutton Hoo Press, which was founded in 1989 by the poet C. Mikal Oness, and is run by him and his wife, Elizabeth. r PQ8519.A5A23.

Next time, in the final instalment of our USTC conference showcase, we look at items in our collections which relate to the LGBTQ+ community.

Briony Harding

Assistant Rare Books Librarian