The role of Astronomy in the establishment of the University Computing Laboratory in St Andrews

On the 4th January 1965 the University of St Andrews Computing Laboratory started a full-time computer service in St Andrews. In celebration of its Silver Jubilee in 1990, the Computing Lab issued a special supplement to its newsletter with reminiscences of those early days from a number of people closely associated with the start of the service: Professor D Walter N Stibbs, Professor Jack Cole, Dr T Richard (Dick) Carson and Sheila Hill. In a new series on the blog, we are republishing these articles alongside images from the University archive which document the history of computing services at the University.

The role of Astronomy in the establishment of the University Computing Laboratory in St Andrews

by Professor Walter Stibbs (1919–2010)

“On 28th July 1959, I was interviewed by the University Court for the post of Napier Professor of Astronomy and Director of the University Observatory. In the course of that interview, I explained to the Court that modern astronomy and astrophysics required substantial computing facilities for theoretical work on stellar structure and evolution, and for data analysis. Although the Court made no promises, I indicated that if I accepted the appointment, I would be pressing hard for a computing laboratory in the University. The Court was aware of the fact that, although I was lecturing at Oxford, I had a formal connection with the UK Atomic Energy Authority with access to the best computing facilities in the United Kingdom, and they eventually agreed to my request to spend two days per fortnight in the Theoretical Physics Division at Aldermaston to continue with my work there during the first year of my appointment to St Andrews at the beginning of the academic year 1959–60.

One of the members of my Group at Aldermaston was Dr T R Carson, who joined the staff at the University Observatory in October 1960 to continue with our work on stellar opacity. At that time, the Department of Astronomy had the greatest expertise in the use of the most modern computers available. During the previous five years, we had worked our way through four generations of computers, from the AWRE Ferranti Mark I*, the English Electric DEUCE, the IBM 704, the IBM 709 to the IBM 7090. The Ferranti Mark I* was the seventh, and a fast version, of the series that evolved from the original Ferranti Mark I at Manchester. It had paper-tape input and output with a basic word length of 20 digits using 12 cathode-ray tubes for storage with 64 words per tube, and a magnetic drum with a storage capacity equivalent to 512 tubes or 32,768 words, and with fast transfers between drum and tube storage for processing in the arithmetical units. Although the instruction set was extremely awkward, it was an interesting and useful machine to begin with. The English Electric DEUCE, designed at the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington by Wilkinson, was a card input and output machine with drum storage, and it was the fastest machine available at that time for problems involving linear algebra. When the IBM 700 series came along, we used the 704 with 8K 36-bit words in magnetic core storage. Together with four magnetic drums, each with 8K words, and 10 tape units with a density of 33 words per inch, it was the largest machine in Europe at the time. This was replaced by the 709 in the 32K word fast-store version, followed by the superlative transistorised version, the 7090, with 32K words in core storage. My group became major users of these computing facilities, and this helped to give St Andrews a head start in the drive to establish a computing laboratory in the University.

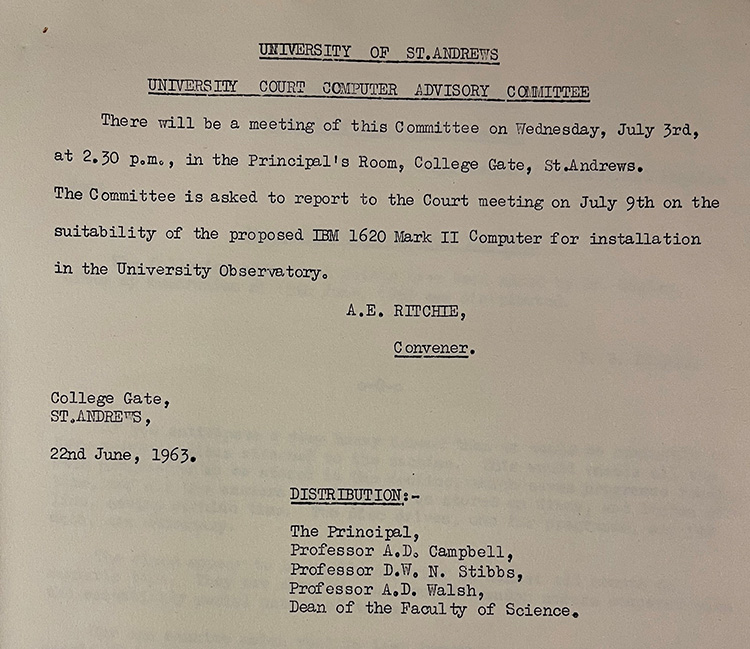

In the absence of digital-computing facilities in St Andrews at the time, Dr Carson and I obtained during 1962 a substantial grant from the SRC to continue with our work on stellar opacity using the IBM 7090 at their Data Centre in London, but I continued to press for a computing laboratory for the University in general and, as a consequence of discussions that I had with Principal Knox, a Senate Computer Committee was set up and I was invited by him to become its Chairman. He indicated that he was already in touch with the University Grants Committee concerning funds and that his initiative was being considered. His case for St Andrews was based not only on the need but also on the expertise available. Meanwhile, Queen’s College Dundee, which was at that time still a part of the University of St Andrews, had accepted the offer of a second-hand machine, and it was consequently recognised that the initiative was specifically for a larger and more modern machine for the St Andrews Colleges.

As I was well known in IBM circles, I approached them for assistance and found them enthusiastic to have an IBM machine in the University, and they indicated that they would make a generous contribution towards the cost. Having visited the IBM factory at Greenock, where I operated one of the first of their disk systems installed in the United Kingdom, I became convinced that the way ahead was core plus disk storage, and I drew up a specification for an IBM 1620 Model II system with the largest magnetic core storage then available with that system, and three units of disk storage including the monitor, and with high-speed card input and printer. This was regarded by some as a radical departure but, although brought up on magnetic tapes and drums, I was convinced that the future lay with disks. In any case, with the possibility of only limited funds, already quoted to me by Principal Knox as being around £60,000, the specification had to be not only modern but modest.

The building programme on the North Haugh was going ahead and I proposed that the Computing Laboratory should be in the Mathematical Institute and this was agreed. However, Principal Knox asked me whether, in the event that any funds were forthcoming before the building was completed, I would be prepared to establish the Computing Laboratory at the University Observatory and operate it for the Court without any increase in staff. Although it did not suit my development programme for Astronomy, I intimated that in those circumstances I would defer my plans to convert the Optical Laboratory on the Ground Floor of the Scott Lang Building into the Observatory Library in order to accommodate the Computing Laboratory. I was less than happy about the question of staff, and I indicated that in the long term, a post would have to be created for a Director of the Computing Laboratory but I would be prepared to act in that capacity for a short time if the Court so wished. It was soon thereafter that Principal Knox informed me that the University Grants Committee had allocated £60,000 and I promptly agreed to stand by my undertaking.

The computer was manufactured in Canada and delivered to the University Observatory early in October 1964. At that time it was the largest system of its kind in Europe, as a consequence of which Dr Carson and I were subsequently in demand for attendance at international meetings. The physical planning of the Laboratory and the layout of the equipment was carried out by myself and Dr Carson in consultation with the IBM engineers. The Computing Laboratory was visited by [Principal] Sir Malcolm Knox in December 1964 for a brief ceremony of inauguration at which a message of welcome was produced for him on the 1443 high-speed Printer, followed by a statement of the Archimedes Cattle Problem and a solution in its restricted form. It was a pleasant and historic occasion.

Dr Carson was relieved of teaching duties during the session 1964–65 to manage the Computing Laboratory and a regular operator service was provided early in January 1965. All members of the Astronomy staff, as well as our research students, rendered invaluable assistance in the operation of the computer until the management of the Computing Laboratory was taken over by Dr A J Cole when he was appointed as its Director in October 1965. When the Mathematical Institute was completed some eighteen months later, the Computing Laboratory was transferred to that location, and the University Observatory was then able to go ahead with its development programme and devote all of its effort to the astronomical work for which it became known nationally and internationally.

In retrospect it is gratifying to note that, although heavily involved with other matters, I was able with the invaluable assistance of Dr Carson to establish a Computing Laboratory within four and a half years of indicating to the University Court in my interview that, if appointed to the Napier Chair, I would be pressing for a University Computing Laboratory in St Andrews, and it is therefore a particular pleasure to be celebrating now the 25th anniversary of the formal inauguration of the Laboratory by Sir Malcolm Knox.”

There are papers of Professor Stibbs held in the manuscript collection as ms38915.

The next instalment will be an extract from the 1990 account by Dr Thomas Richard (Dick) Carson.

[Reproduced from the 1990 Computing Lab Newsletter]