Notaries and their networks in St Andrews, 1466-1560

Scottish History PhD candidate Kate McGregor has been has been working for the past year as a Research Assistant on a project investigating notaries and their networks in late medieval St Andrews, supported by generous funding from the St Andrews Local History Foundation, administered by The Burnwynd Trust. Here are some of the highlights from her research.

Late medieval Scottish notarial practice was sophisticated, complex, and infused with ancient legal traditions governed by a powerful ecclesiastical authority. The Burgh Records of St Andrews offer a fascinating insight into the identities of notaries operating in the town from the mid-fifteenth century to the advent of the Reformation.

With the generous funding provided by The Burnwynd Trust’s St Andrews Local History Foundation Award I have spent the past year delving into the St Andrews burgh records to uncover hitherto untold stories of urban life in medieval Scotland. This project, supervised by Mrs Rachel Hart, Senior Archivist and Keeper of Manuscripts and Muniments at the University of St Andrews, and Professor Michael Brown, Professor in Scottish History at the University of St Andrews, aimed to investigate notaries who operated in St Andrews from 1466 to 1560 and their wider networks. It followed on from a recently-completed pilot project, funded by The Scottish Medievalists, in which Mrs Hart and Professor Margaret Connolly, Professor of Palaeography and Codicology in the Schools of English and History, surveyed and identified notarial instruments within the University’s muniment collection and did sample imaging. All data for my study has been collected from the St Andrews Burgh Records, specifically B65/23 Burgh Charters and Miscellaneous Writs. These are housed with and managed by University Collections in the St Andrews University Libraries and Museums on behalf of Fife Council, the successor authority to the Burgh of St Andrews.

A notary in late medieval Scotland was a legal role. Notaries could draw up wills, contracts of marriage, compile evidence for courts, and formulate deeds or documents which detailed the transfer of land through instruments of sasine, the most common survivals within the burgh charters. Such an instrument would record the transaction, the parties or clients involved, as well as the names of the notary and witnesses to the deed.

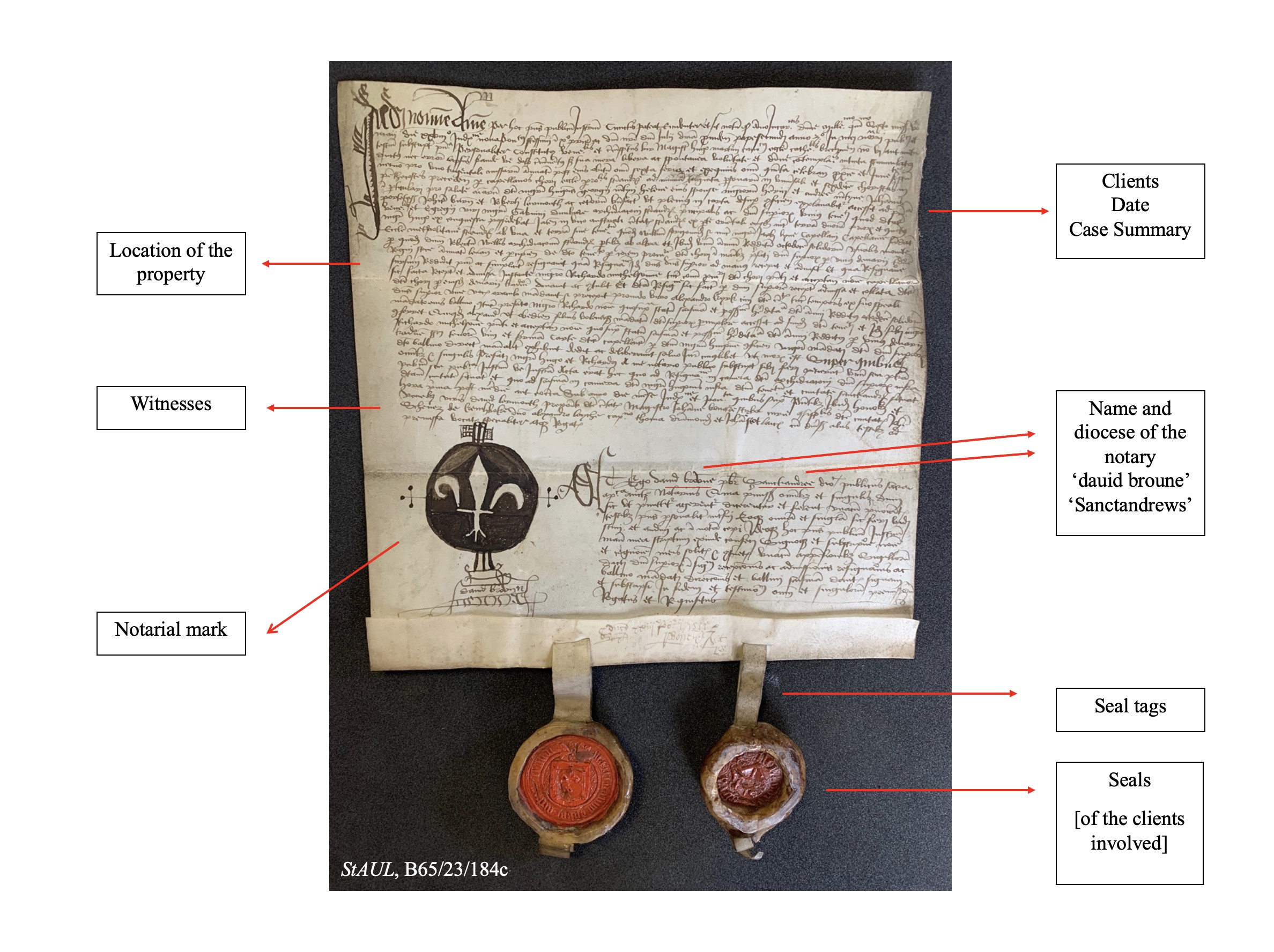

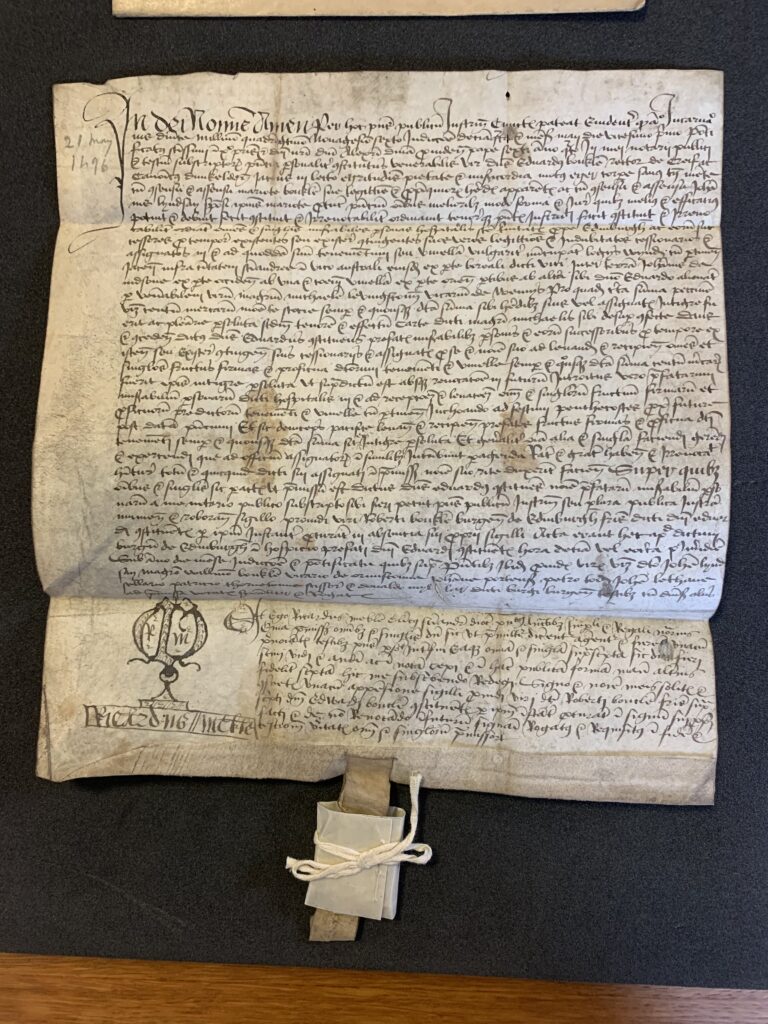

Generally, all the instruments, written on parchment in this period, follow the same pattern. A main paragraph in Latin summarises the case, the clients involved, the location of the property being transferred, the annual rent of the property, and the date of the transaction. Witnesses are then listed at the very end of this paragraph. A second smaller paragraph on the right-hand side of the bottom of the document usually details the name and diocese of the notary – this is his ‘notarial attestation’. Opposite this smaller paragraph, on the left-hand side of the document, is the notarial mark, or marks. Sometimes the seals of the clients are attached to the bottom of the document.

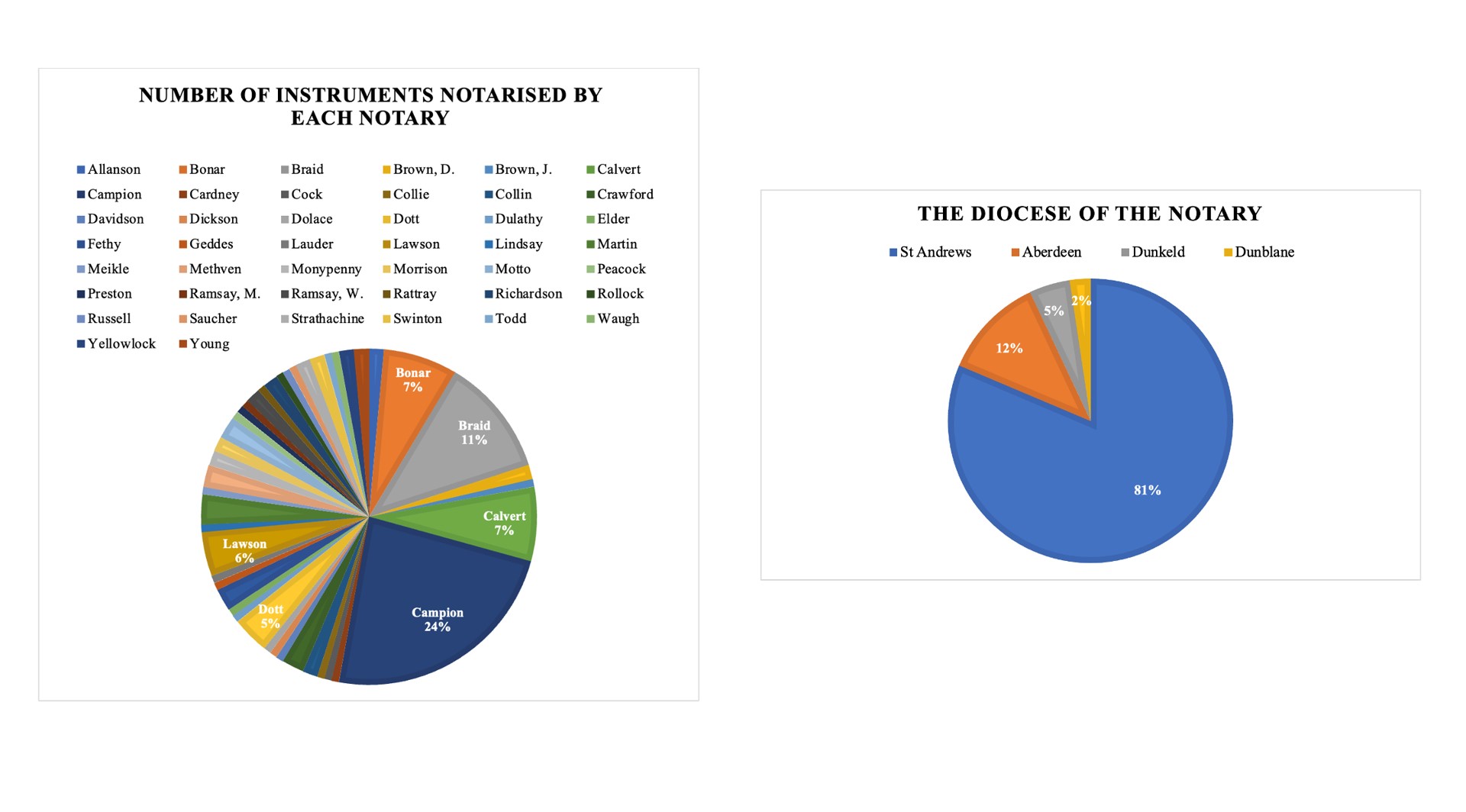

Between 1466 and 1560 at least forty-five notaries public operated within the burgh of St Andrews. The average length of time in which a notary was active in St Andrews was 7.02 years (316 years. 45 notaries. 316 divided by 45 equals 7.02 – the mean.) By far the most prolific notary in late medieval St Andrews, according to the burgh charters, was Simon Campion, who wrote 24% of surviving notarial instruments in the B65/23 series from 1466 to 1560. This pie chart clearly shows the Campion’s dominance. Active from 1478 to 1503, Campion gained his authority to work as a notary from the diocese of St Andrews. As well as notarising thirty-three, or perhaps thirty-four, transfers of property or land Campion also witnessed several other notarial instruments.

Notaries within St Andrews almost exclusively held their authority to authenticate legal transactions from the church. The Burgh Records show that most notaries in St Andrews (81%) were local, with permissions from the Diocese of St Andrews, 81%. It is, perhaps, unsurprising that a notary would gain authority from the diocese in which they were operating. As you can see the other dioceses included Aberdeen, Dunblane and Dunkeld.

Notaries within St Andrews almost exclusively held their authority to authenticate legal transactions from the church. The Burgh Records show that most notaries in St Andrews (81%) were local, with permissions from the Diocese of St Andrews, 81%. It is, perhaps, unsurprising that a notary would gain authority from the diocese in which they were operating. As you can see the other dioceses included Aberdeen, Dunblane and Dunkeld.

It is possible to deduce from the extant burgh records other positions, mainly ecclesiastical appointments, that these notaries additionally held. This gives us a broader understanding of the responsibilities and social position of notaries within the burgh. For example, John Bonar was by 1488 the vicar of Crawfordlindsay (B65/23/111c). By 1513 Bonar was instead listed as the vicar of Eaglescraig (B65/23/199c). Some notaries were directly involved in the administration of the burgh: Bernard Crawford was a baillie of St Andrews in 1526 (B65/23/238c). Notaries also held property within the burgh: Simon Campion in 1503 held a tenement lying in South Street (B65/23/175c). By virtue of their trusted position notaries acted as a bridge between local gentry, burgh and university officials, and citizens of the town.

Most clients noted in the notarial instruments were property-holding men. Local gentry are named, for example Sir Edward Bonkil, knight and cleric, as rector of Crieff and canon of Dunkeld. On his deathbed in 1496 he transferred a property which he held in St Andrews to the Trinity Hospital in Edinburgh. The rent from this property was in part to fund the hospital. The tenement was on ‘Logys Wynd’, now known as Logies Lane (B65/23/145c).

University officials were also often clients in these notarial instruments. David Meldrum canon of Dunkeld and Principal of St Andrews was a client in 1496 (B65/23/144c and B65/23/172c). Likewise, Gavin Dunbar, archdeacon principal of St Andrews, was a client in 1506 (B65/23/184c and B65/23/193c although 193c no longer survives in the original). Other major figures within the medieval church also appeared as clients, for example James, Bishop of Moray and Andrew, Archbishop of St Andrews (B65/23/212c). Leading guildsmen, burgh officials and members of the burgh council were clients too, such as James Forrett, named as a baillie of St Andrews in 1496 and in 1503 (B65/23/144c), and citizens of St Andrews most notably baxters, or bakers.

Women were often clients, or co-clients listed alongside their husbands, and are most commonly referred to by their maiden names as was normal. In cases of property law or disputes of inheritance which depended on the maternal line it was vitally important to recognise, and record, the maiden familial name.[1]

This study has shown that the university, diocese, and burgh were all highly interconnected, geographically, and socially, and that it was the notary that acted as a bridge between these connections. The expertise, and legal authority, of the notary legitimised and actualised these networks through authenticating economic transactions.

Notaries were the primary vehicles through which legitimacy and authority operated, and was translated, in these instruments. It is striking how many notaries acted as witnesses on other notarial instruments. For example, in 1505 John Bonar was a witness on an instrument notarised by Robert Lawson (B65/23/182c). This interconnectivity suggests a distinct bond between notaries, a community of sorts, which both notarised and witnessed instruments and served to further legitimise transactions within the burgh.

In uncovering the identities, and networks, of notaries in St Andrews this micro-historical study has contributed to the burgeoning field of urban and social histories within medieval Scotland. There is much left to explore and discover and in my next post I will be turning to the names and identities of these notaries and their exquisite, and personal, notarial marks.

Kate McGregor is a second-year PhD candidate in Scottish History at the University of St Andrews, supervised by Professor Michael Brown and Dr Amy Blakeway, and fully funded by the Ewan & Christine Brown Postgraduate Scholarship in the Arts and Humanities. Her PhD thesis explores foreign policy during the adult reign of James V, King of Scots, 1528-1542. She completed her undergraduate degree at St Andrews and her MPhil at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Follow Kate on Twitter @ks_mcgregor for even more history content!

[1] Elizabeth Ewan and Maureen Meikle (eds.), Women in Scotland c.1100-c.1750 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 1999).

The Notarial marks interest me. Are they unique to each notary and can a notary have more than one mark? Thanks